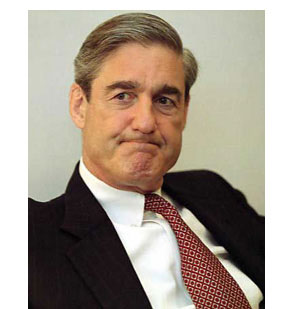

As FBI director Robert Mueller takes on the daunting task of reforming his agency, some of the criticisms he’s faced from FBI whistleblower Coleen Rowley and congressional inquisitors echo charges that arose more than 10 years ago during Mueller’s handling of the investigation into the Bank of Credit and Commerce International.

At the time, the criticism of Mueller focused on his willingness to defend the Justice Department and its employees, and his refusal to admit error in an investigation that, critics alleged, went awry.

As assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department’s criminal division in the early 1990s, Mueller oversaw the department’s investigation into BCCI, which was eventually found to be involved in a host of criminal activities, including international money laundering, the support of global terrorism, and the selling of nuclear technology, according to a 1992 congressional report on the bank.

Mueller came to the Justice Department after U.S. attorneys in Tampa, Fla., had brought an indictment against BCCI in 1988 for laundering drug money. Congressional critics, including Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., argued Tampa investigators “failed to recognize the importance of information they received concerning BCCI’s other crimes, including its apparent secret ownership of First American,” then the largest bank in the Washington area. Kerry and his investigators said the Justice Department failed to connect the dots and allowed BCCI to continue its illegal operations in the United States and abroad.

A 1992 report by a Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee, chaired by Kerry and Sen. Hank Brown, R-Colo., stated that “the decision to stop investigating BCCI appears to be an example of poor communication, overwork, under-staffing, inadequate understanding of the meaning of information in the possession of Justice, and a flawed prosecutorial and investigative strategy” — a summary that sounds as though it could come from a congressional report about the FBI and Sept. 11.

“Mueller back then was faced with a very similar situation,” says Jim Winer, a Washington lawyer who served as a congressional investigator into the BCCI probe. “The prosecutors in Tampa had made a very narrow case against BCCI, when BCCI was a much more substantial, international problem. They indicted local money-laundering accounts without looking at the fact that the bank actually had $4 billion missing and was engaged in massive fraud all over the world, including its secret and illegal ownership of what was then the largest bank in Washington, D.C., First American Bank.

“There was a failure of coordination between FBI and CIA that was very substantial, and allowed a criminal enterprise to take over the largest bank in the Washington metro area,” he says. “And what Bob Mueller perceived his job to be was to defend the department for institutional reasons.”

Kerry, who has known Mueller since their New Hampshire prep school days, now downplays his confrontation with him over the BCCI probe 10 years ago, noting that he supported Mueller’s nomination last summer to be FBI director. “I don’t think you would call it a dust-up, and I don’t think anyone characterized it as such at the time,” Kerry says. “It was a difference of opinion over prosecutorial judgment about a particular case. It’s just one of those things that happen around here.”

But Kerry was severely critical of the department’s handling of the BCCI investigation, and a report by his committee castigated the Justice Department for “failing to provide adequate support and assistance to investigators and prosecutors working on the case against BCCI in 1988 and 1989,” a year before Mueller took his position at the department.

Back then, testifying before the Senate about charges that his new subordinates had botched the job, Mueller staunchly defended his people.

“The allegation that prosecutors have deliberately failed to do their duty is absolutely and categorically false,” said Mueller, under questioning by Kerry at a contentious hearing in November 1991. “The department has been criticized for reported delays in bringing indictments against BCCI and its officers. And I must say that the claim is simply untrue.”

Defending the institution was also Mueller’s first instinct when the FBI came under criticism last month. After a pair of memos — one from before Sept. 11 from Arizona FBI agent Kenneth Williams, and another written last month by Minnesota agent Coleen Rowley — raised doubts about the FBI’s performance both before and after Sept. 11, Mueller went on the defensive.

“The agent in Minneapolis did a terrific job in pushing as hard as he could to do everything we possibly could with Moussaoui,” Mueller said at a May 8 hearing of the Judiciary Committee. “But did we discern from that that there was a plot that would have led us to Sept. 11? No. Could we have? I rather doubt it.”

That led Rowley to charge “that a delicate and subtle shading/skewing of the facts by [Mueller] and others at the highest levels of FBI management has occurred.” She also claimed that certain facts “have, up to now, been omitted, downplayed, glossed over and/or mischaracterized in an effort to avoid or minimize personal and/or institutional embarrassment on the part of the FBI and/or perhaps even for improper political reasons.”

Mueller initially marked Rowley’s letter confidential, but copies were sent to senators, and an edited version was obtained by Time magazine. Only after the memo was made public did Mueller concede, “I cannot say for sure that there wasn’t a possibility we could have come across some lead that would have led us to the hijackers.”

He made a similarly steadfast defense when Sen. John Edwards, D-N.C., a member of the Senate Judiciary committee, complained that his staff was not told of Williams’ memo — which urged the counterterrorism unit to probe flight schools for possible al-Qaida terrorists — or concerns from the Minnesota office about the FBI’s handling of the Zacarias Moussaoui case when the staff was briefed in January by FBI counterterrorism chief David Frasca and Spike Bowman, the FBI’s associate general counsel for national security affairs.

Winer says it is not surprising that Mueller, a former Marine who earned a bronze star in Vietnam, offered a steadfast defense of Bowman and Frasca. “The first thing, he was going to defend his people against what he perceived to be political attacks,” Winer says. “It so happened that the political attacks were utterly accurate and fair, but he was still going to defend his people as an institutional matter, because Marines defend their people.”

Mueller has repeatedly assured members of Congress that the FBI is conducting a thorough review of its shortcomings leading up to the Sept. 11 attacks. Of course, the overhaul of the FBI is a much larger task than the one Mueller faced as assistant attorney general a decade ago. But as he was in the BCCI case of more than 10 years ago, Mueller is being called on by Congress to clean up a mess made on somebody else’s watch, and so far, as it was then, Mueller’s instinct seems to be to defend his institution before all else.