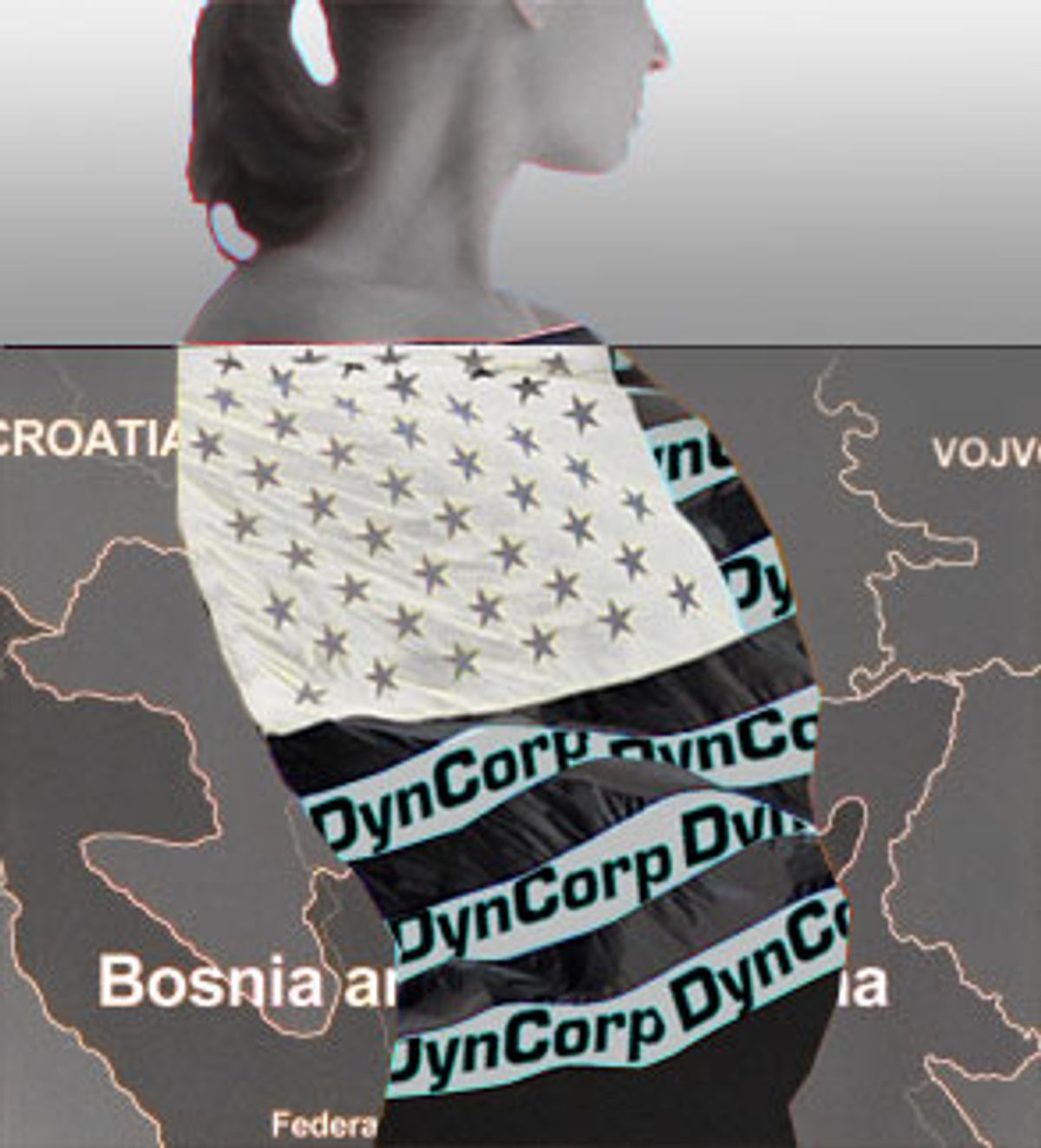

In early 2000, the U.S. Army received information that private contractors working at a base near Tuzla, Bosnia, were purchasing women from local brothels. Some of the women may have been as young as 12, and some were being held as sex slaves, the sources alleged.

Investigations by the Bosnian police and the U.S. Army confirmed the gist of those reports, turning up significant evidence of wrongdoing by at least seven men -- including at least one supervisor -- employed by Reston, Va.-based DynCorp. Despite those findings, no one ever faced criminal charges or prosecution in either Bosnia or the United States.

The investigation at Camp Comanche in Bosnia is at the heart of a lawsuit filed by former DynCorp mechanic Ben Johnston, who says DynCorp wrongfully fired him for assisting the Army Criminal Investigation Command in its probe of the camp. The investigation and its results, along with allegations made in a similar whistleblower lawsuit against DynCorp in the U.K., have brought to light a critical loophole in efforts to police the shadowy world of private military firms, a booming industry that's now worth almost $100 billion a year.

Thanks to a combination of factors -- the jurisdictional conflicts of American law, the immunity provided to these contractors by international treaties, and the underdeveloped police agencies in host countries -- many crimes committed by private military personnel while based overseas will likely go unpunished, just as they did in Bosnia.

"You have a situation where employees of these companies can commit serious crimes and the only enforcement we have against them is the law of the marketplace," says Peter W. Singer, an Olin fellow at the Brookings Institution, who has studied the companies for seven years. "That's proven to be insufficient."

These private military firms were thrust into the international spotlight in April 2001, when Aviation Development Corp. was involved in the accidental downing of a missionary plane in Peru. Aviation Development, on contract with the CIA to look for drug traffickers, may have misidentified the missionary's plane as a drug transport, which was then shot down by the Peruvian military. According to media reports, the United States has paid an undisclosed sum to the family of Veronica and Charity Bowers, who were killed in the incident, and to the Baptist missionary group they belonged to, but stopped short of admitting culpability. Aviation Development has never publicly accepted responsibility, and the U.S. government has never publicly accused the company of wrongdoing.

Another incident, covered in great detail last March in the Los Angeles Times, implicates the private military company AirScan in planning and executing a 1998 attack by Colombian military forces against local rebels, which may have resulted in the accidental bombing of a small Colombian town. At the time, AirScan was under contract to Oxy Petroleum to track rebels who might threaten Oxy's pipeline. Eleven adults and seven children were killed when a bomb exploded in the town of Santo Domingo, and according to the Times no one has been held accountable for their deaths. The Colombian military denies it bombed the town during the attack. AirScan denied involvement, according to the Times.

Critics say those cases and others show how private companies are in effect being used to distance the U.S. government from messy international conflicts. Although no Americans were directly accused of criminal wrongdoing in Peru or Colombia, the incidents underscore the troubling lack of accountability applied to the companies, they say.

The Peru incident helped provoke one of those critics, U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill., to introduce a bill in April 2001 that would have stopped government funding for private military companies in the Andean region. But no action has been taken on the bill. Ed Soyster, a spokesman for military contractor MPRI, says such critics are wrong. As the U.S. military shrinks its forces, he says, private companies will be needed to fill the gap with an array of support services -- from providing mechanical services and building military bases to training foreign armies. "The idea that somehow there's no accountability because the government paid a company" to do a job, instead of doing that job itself, doesn't hold up, Soyster says. "It won't hold up with the media. It won't hold up with the courts." Employees of MPRI are held accountable by the local laws of whatever country they're in, he says. If there is a breakdown in prosecuting criminal behavior, that breakdown is the problem of that government. After all, Soyster says, a company doesn't have the power to arrest people, try them or send them to jail.

But Singer points out that the laws and enforcement capabilities of the host country can sometimes be inadequate -- and that contractors have no incentive to expose their employees to prosecution.

"Typically when someone commits a crime, the legal system of a state is responsible for prosecuting that crime," Singer says. "But these companies are operating in areas where the local legal system is either unable or unwilling to hold these guys accountable. So, what you have happening is that these guys are American, but they're not being held under American law because they're inside Bosnia or Kosovo or wherever. And then there's no capacity to carry out enforcement by the locals. And if the locals do attempt to do something, the company pulls them out [of the country] because they'd rather not see their own employees get prosecuted. "It's bad for business."

The scenario Singer describes is almost exactly what happened when Bosnians and Americans began to complain that DynCorp employees were involved in the sex-slave trade in Bosnia.

In the U.K. suit, former DynCorp employee Kathryn Bolkovac contends that she was laid off after reporting that her co-workers were complicit in the rampant forced-prostitution industry in the Balkans. Bolkovac was part of the American contingent of the U.N.'s International Police Task Force, which is contracted to the U.N. from DynCorp, and she claims other members of the task force were patronizing brothels where women were forced to work as prostitutes. Like the men accused of wrongdoing in Johnston's case, none of the accused police officers has faced prosecution.

"[IPTF] officers and ... [overseas] contractors share one major characteristic: impunity," Martina Vandenberg, a women's rights researcher for Human Rights Watch told a House International Relations Subcommittee in April.

One problem, as laid out by Singer, and reiterated by Vandenberg in a recent telephone interview, is that for various reasons the host country -- in this case Bosnia-Hercegovina -- can't or won't prosecute U.S. contractors.

Often, according to Singer, the local police forces don't have the resources to prosecute such crimes, or they're corrupt, or they're just not interested in pursuing crimes committed by U.S. contractors. But at Camp Comanche in Bosnia, two DynCorp employees escaped prosecution through a loophole created by a combination of bureaucratic confusion and corporate attempts to resolve the situation by immediately pulling accused workers out of Bosnia.

The investigation was opened when the Army's Criminal Investigation Command (known as CID) received allegations that DynCorp employees were buying women to use as sex slaves. When CID started the investigation, the Army's Office of the Staff Judge Advocate for Bosnia-Hercegovina said that the office did not have jurisdiction to prosecute civilian contractors. So the CID conducted its investigation and turned it over to the Zivinice, Bosnia, police.

But it wasn't clear whether the Bosnian police had jurisdiction, either. When the investigation began, according to CID's report, the judge advocate's office was under the impression that contractors were protected from Bosnian prosecution by the Dayton Peace Accords, which govern the relationship between Bosnia-Hercegovina and the international stabilization forces in the region. The issue was clarified somewhat when the Army CID found an "Interpretation of the Agreement Between NATO and the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina," which allowed for Bosnian prosecution of contractors. CID agents then handed the case over to the Bosnian police. But according to Vandenberg, who interviewed Zivinice's police chief during a Human Rights Watch investigation in March 2001 -- more than a year after the incident -- the Bosnian police never developed such a nuanced understanding of the Bosnian agreement with NATO. When she interviewed the chief, she says, he still believed that he did not have the ability to arrest DynCorp employees.

The police chief told her, "'We would have wanted to prosecute -- but we couldn't prosecute because we can't arrest them,'" she recalls. "As far as they're concerned, these are members of the international community with immunity."

The issue became moot, however, when the Army and DynCorp pulled the accused men out of the country. The act effectively ended all investigations and ensured that the men would never face criminal charges unless they returned to Bosnia-Hercegovina, and perhaps not even then.

When it comes to the DynCorp employees provided to the U.N., however -- subjects of the allegations raised in the Bolkovac case -- the issue of immunity is far less gray. Stefo Lehmann, the U.N. spokesman for Bosnia-Hercegovina, says officers of the U.N.-supplied International Police Task Force are not subject to Bosnian law, as part of the agreement between the U.N. and Bosnia-Hercegovina. If IPTF members are accused of a crime, Lehmann says, they are investigated by a U.N. internal investigations unit, and if evidence is found, those persons are repatriated to their home countries for punishment.

Lehmann confirmed that out of about 10,000 police officers who have served in the police force at one point or another, roughly 15 have been sent home for wrongdoing. The majority of them -- nine, according to Lehmann -- have been from the American contingent. Six of these, he confirmed, were sent home for problems related to the solicitation and prostitution, although none, he stresses, was charged with trafficking women. And Lehmann says he knows of none who have been charged with a crime upon returning to the United States.

Lehmann says the American police are unique in that they have been recruited by a private contractor -- DynCorp. Other contingents tend to be made up of the sponsor countries' own national police, he says, and as a matter of national pride, they often send their best officers.

Whether the employees are sent by the U.N. or fired by DynCorp, a second problem emerges once they're home, Singer says. These contractors are not prosecuted in the U.S. because, as Army Materiel Command staff judge advocate David Howlett says, U.S. law does not cover most common crimes when those crimes are committed in a foreign country.

Congress took steps to close this loophole with the passage of the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act of 2000. Theoretically, the law allows for prosecution in U.S. courts of contractors working alongside the military overseas, but the law is far from comprehensive.

For one thing, the regulations to govern just how the statute works have yet to be written. So while the law is technically in effect, how it is to be carried out -- how prisoners would be handled, who would defend suspects, which federal magistrates would handle cases -- is unclear. Even when the needed regulations are written, it will take another 90 days before they become active.

"As far as I know, this act doesn't have the regulations that are designed to implement it yet," Howlett says, "and it hasn't ever been used [to prosecute] a person who committed a crime overseas."

Howlett says in a rare instance the law could be used without those regulations, but calls such a possibility unlikely.

"Let's say one of our contractors from the Army Materiel Command that we have over in Southwest Asia right now kills another contractor, and it's a murder case. The host nation probably doesn't want to deal with it because it's two Americans and it doesn't bother their sovereignty a lot. That might be a case where we might say: 'All right, let's try and bring this person to justice using this method,'" Howlett says. "It's my hope personally that before the situation arises, we'll have these regulations."

Singer, at the Brookings Institution, also points out that the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act covers only American citizens working for American forces. If MPRI employees go to Afghanistan to train the new Afghan army, for example, they will probably technically be employees of Afghanistan, not of the United States. And the act does not cover workers contracted to the U.N.

"The U.S. government has absolutely no criminal jurisdiction to prosecute civilian police officers who serve with U.N. missions abroad," Vandenberg explains. So, as the U.N.'s Stefo Lehmann says, officers accused of committing a crime in Bosnia are immune from Bosnian prosecution and are sent home by the U.N. to be punished. But there is no U.S. law that would allow them to be prosecuted at home.

Vandenberg says that she has heard of efforts currently underway to expand the Military Jurisdiction Act of 2000 to include all U.S. contractors working overseas, but to the best of her knowledge no bills have been introduced. MPRI's Soyster says he would not be opposed to such a law, because he'd "rather be tried in a U.S. court than a Bosnian court." But even if such laws are introduced, Vandenberg expects a significant amount of legal wrangling before they take effect. She doesn't see a solution in the immediate future.

Vandenberg points out that the International Criminal Court, which is scheduled to be born on July 1, may technically have the jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed by military contractors. But the administration of President George W. Bush publicly opposes the court and has already announced that it will not participate in U.N. peacekeeping missions unless Americans in those missions are granted immunity from the court. Even if that were not the case, Vandenberg says, the court would probably not pursue cases such as those raised by the DynCorp lawsuits, as it will be focused more on large-scale crimes such as genocide.

"What you have," Vandenberg says, "is a climate of complete impunity."

Shares