"He walked down Marbeuf onto the Champs-Elyseés. At twilight the city throbbed with life, crowds moving along the avenue, the smells of garlic and frying oil and cologne and Gauloises and the chestnut blossom on the spring breeze all blended together. The cafés glowed with golden light, people at the outdoor table gazing hypnotized at the passing parade. To Casson, every face -- beautiful, ruined, venal, innocent -- had to be watched until it disappeared from sight. It was his life, the best part of his life, the night, the street, the crowd ... He'd made love all his life ... but this, a Paris evening, the fading light, was his love affair with the world." -- Alan Furst, "The World at Night"

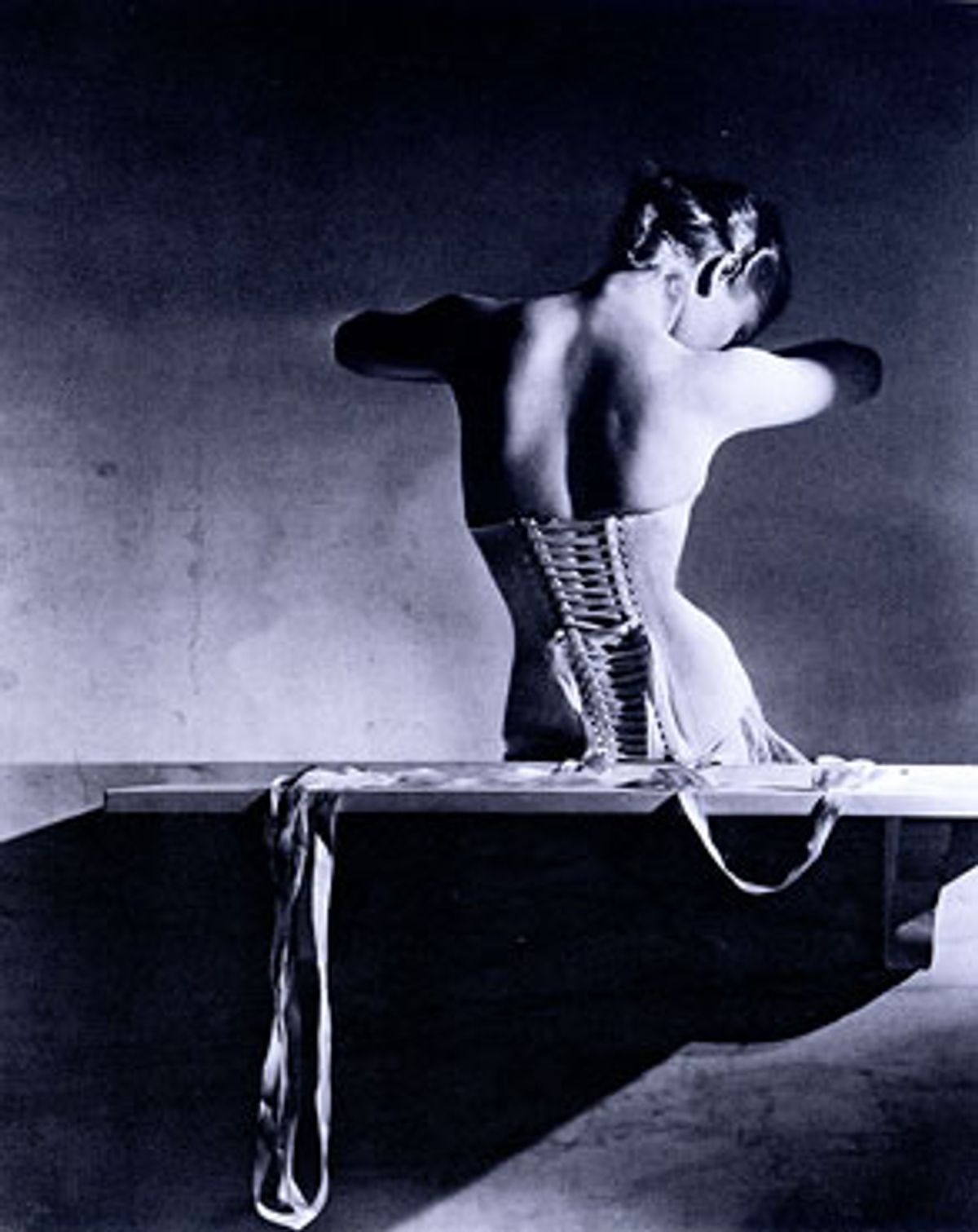

She sits with her back to the camera, her long, elegant neck arched down, a hint of profile as her head inclines to meet her right shoulder, as if she were hiding her face, or were caught at the beginning of a luxuriant stretch. The light and shadows accentuate the deep concave slopes of her lovely back, and draw our eyes downward to the unlaced corset, its satin ribbons falling behind her, spilling over the edge of the marble ledge she leans against, looking for all the world like discarded party streamers. It could be anytime between midnight and dawn, as the silence of the city outside descends, pushing the revels of the night further back into memory.

Actually it was just after midnight one evening in late 1939. The city was Paris. The man behind the camera was the great German fashion photographer Horst P. Horst. And the subject was not the model but, ostensibly, the Mainbocher corset she was wearing. Horst, along with his colleague and lifelong friend (and, briefly, his lover) George Hoyningen-Huene, pioneered what we've come to regard as the essence of classic fashion photography -- silver gelatin prints of elegant and formal stylization. Vogue and Vanity Fair were their main outlets in the '30s, the decade in which they did their most characteristic work, though both worked in fashion photography and portraiture for years after (Hoyningen-Huene died in 1968; Horst just a few years back, in 1999).

It's easy to look at their work as frivolous, the denial of the decade's horrible undercurrents that were to burst forth in 1939 with the outbreak of war in Europe. I prefer to look at it as an early form of resistance, a way of seeing beauty as a vestige of everything civilized and humane. It was a reaction to a time when, as Sir Isaiah Berlin wrote, "all was dark and quiet ... and little stirred, and nothing resisted."

For me, the photo of the Mainbocher corset is the heart of this. It was taken after midnight on the day Horst fled Paris, a few months ahead of the Occupation. (He settled in New York and spent the last few years of the war as a U.S. Signal Corps photographer.) Unlike his other fashion shots of women immaculately groomed for an evening out, this is a photo of undressing. And the model's supplicant pose -- suggesting the weariness, the reflection, even the mournfulness, that come at the end of an evening out -- is vulnerable, exposed in a way that all his other meticulously put-together subjects never were. It's Horst's farewell to the elegance that he had epitomized, an implicit acknowledgment that upholding civilization and humanity would now mean donning other uniforms.

In a few months the Paris fashion houses would be shut down, and French Vogue would be closed after being raided by Occupation forces. (The editor, Michel de Brunhoff, would be discovered working for the Resistance shortly before the end of the war.) The meaning of the photo, a lingering kiss goodbye, was the opposite of what students in the '60s meant by "make love, not war." There is no contradiction in the photo. This was making love as a form of war, an embrace of sensuality as a rebuke to the inhumanity bent on taking over the world. An act of sabotage is no less potent because it takes place in private, with lovers becoming comrades on the most intimate of battlefields.

Shares