These days, ground zero smells like a fairground. The acrid chemical stench that poisoned downtown Manhattan for months has dissipated, and in its place are the summertime scents of hot dogs, cotton candy, roasting nuts and shish kabob, all competing to tempt the hordes of visitors to New York's newest blockbuster tourist attraction.

According to the New York Times, 3.6 million people will visit ground zero this year. There's no longer much to look at -- the expanse where the twin towers once stood is now just a vast construction site -- but people keep coming, disgorged by tour buses that idle nearby. There are giddy high school students in foam Statue of Liberty hats, dour families squinting under visors that read "Ground Zero NYC," religious groups including, on a recent visit, a few dozen Jews for Jesus in matching fluorescent orange T-shirts, middle-aged men staring intently into their camcorders and young guys strutting topless in the summer sun. Last Saturday one woman leaned into her husband and seemed, for a moment or two, to tear up, but mostly people seemed to be enjoying themselves in the perfunctory, listless way of tourists everywhere.

A whole cottage industry has sprung on the site's perimeter, a marketplace to peddle souvenirs of the catastrophe. Besides the aforementioned visors, there are Ground Zero NYC T-shirts and baseball caps. Five-dollar snow globes of the World Trade Center with police cars or fire trucks in the foreground swirl with red, white and blue sequin stars. Stall after stall sells $9.95 "Day of Terror" commemorative books, their covers decorated with pictures of the planes smashing through the buildings. DVD montages of the disaster -- running in a constant loop on the vendors' laptops -- go for $15 to $20.

George Peres, who has been selling stuff on the street for eight years and is finding unprecedented success with 9/11 merchandise, says he sells between 10 and 20 DVDs a day, as well as around 80 books. Across the street, Orlando Hollis, who lives in Washington but comes to Manhattan to peddle his wares, says, "Some of the stuff out here, like showing planes crashing into buildings, that's offensive."

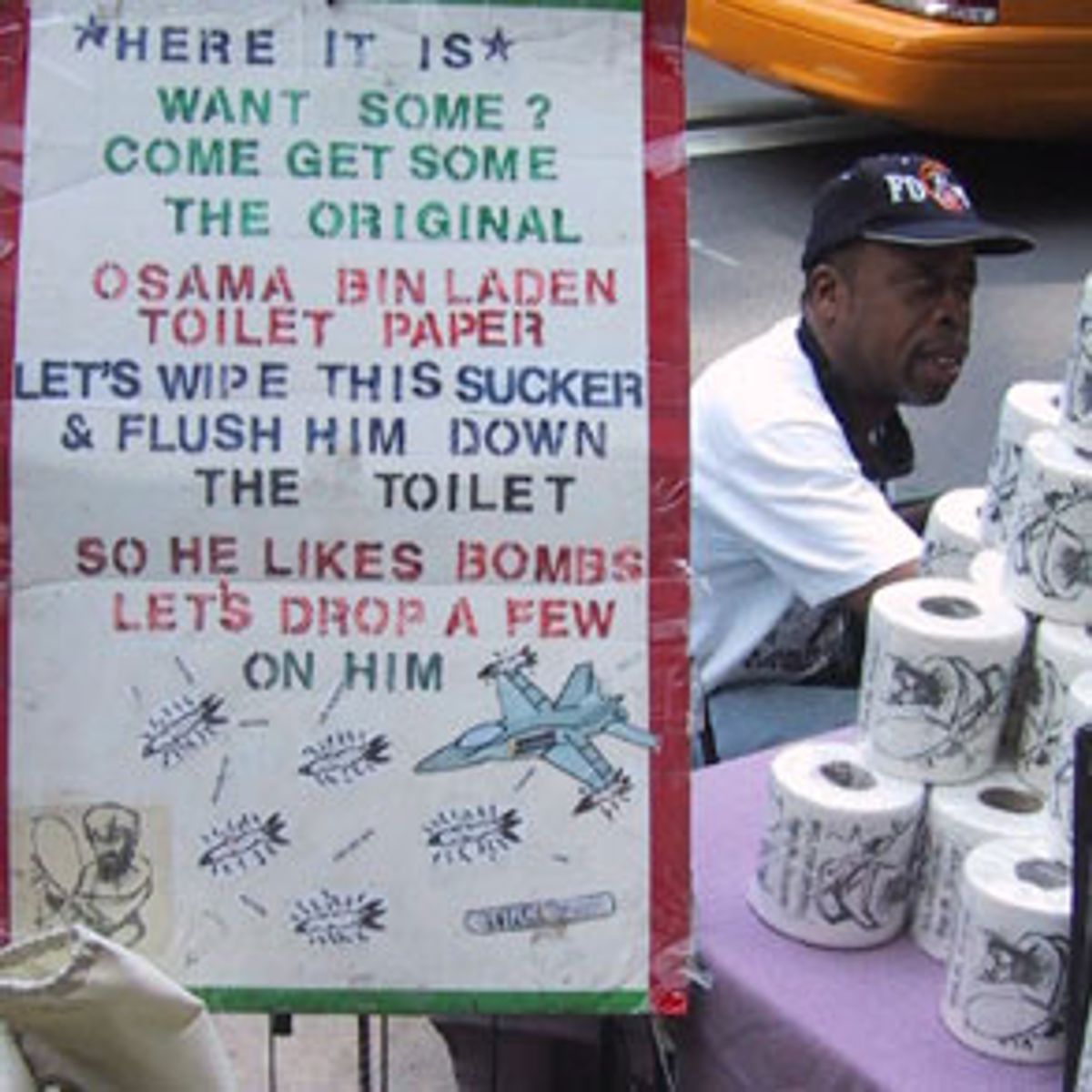

Hollis, who wears an NYPD T-shirt over fatigues, sells Osama bin Laden toilet paper. "Wiping out terrorism!" he calls to passersby. The rolls go for $6 each, with a 50-cent discount if you buy three or more. Hollis has to compete with several other toilet paper purveyors, including one nearby who advertises with a sign saying, "So he likes bombs, let's drop a few on him!" Still, he does OK, selling around 200 rolls a day.

Some people, perhaps many, visit ground zero to pay their respects, to commune with history through the sight of charred real estate, to get a sense of the enormity of what happened. Yet the atmosphere at ground zero is nearly devoid of somber reverence. It feels like just another sentimental landmark, a place for people to get their picture taken so they can tell the folks back home they were there. Amid the brightly dressed crowds, one senses that for those who didn't lose anyone, some inevitable American alchemy has transformed the attacks into entertainment.

Shortly after Sept. 11, the pioneering avant-garde electronic composer Karlheinz Stockhausen ignited worldwide fury by calling the attacks "the greatest work of art there is in the entire cosmos," a statement which spurred a Times of London article asking, "Is this the most hated man in contemporary arts?" He was excoriated for finding aesthetic pleasure in the murder of thousands. His statement seemed to embody the nihilism at the core of a purely aesthetic view of the world, a view which reduced all events to their reflected images and the intensity of their attendant sensations.

Such fey and distanced triviality was supposed to be incinerated by the excruciating reality of the slaughter. Remember how many critics predicted that, having seen true urban devastation, audiences would no longer glory in watching buildings and cities brightly annihilated at the movies? In a gesture toward the new sensitivity, Blockbuster started labeling terrorist-themed videos with the message, "In light of the events of Sept. 11, 2001, please note that this product contains scenes that may be considered disturbing to some viewers."

"Once upon a time, it was fun to watch unthinkable things. But everything is different now," Leonard Pitts wrote in an article that appeared in the Chicago Tribune on Oct. 9.

It turns out that things are much less different than some had hoped. Far from shying away from images of exploding public landmarks, the public hungered for them -- according to the AP, rentals of films like "The Siege" and "Die Hard" spiked after Sept. 11. Much had been made of Hollywood's sensitive decision to delay the release of "Collateral Damage"; in deference to the new sobriety, Warner Brothers waited nearly four months after the attacks to put the movie in theaters, where it quickly became a hit. So did "The Sum of All Fears," with its spectacular nuclear erasure of Baltimore.

Nine months after Sept. 11, the American public is not sickened by violent spectacle. On the contrary, it's almost as if its appetites have been whetted.

The expectation that a gentler world would emerge from Sept. 11's ashes now seems based less on reason than on an apocalyptic vein in American culture, the hovering possibility that one huge inferno can wipe away all our sins. This theme infects not just fundamentalist Christianity -- which has been torn between mourning escalating bloodshed and delighting at the approaching rapture -- but the secular world as well. How else to explain the widely shared hope that the World Trade Center disaster would redeem a craven culture?

The towers had barely fallen when pundits starting breathlessly cataloguing the societal sins they'd taken with them -- irony, narcissism, partisanship, greed. A New York Times editorial opined, "The awful week of death and destruction that has just ended might be the invitation to create a great new generation and a finer United States," while a Sept. 22 think piece about what the attacks portended for reality TV declared that New Yorkers had been "cleansed of the era's more frivolous preoccupations." Writing in the Journal of Higher Education, Martha Bayles barely suppressed her glee, saying, "The events of that day appear to have set off a seismic, even tectonic, shift that, unlike most of the other transformations we now face, feels therapeutic. Is it possible that terrorism is curing our worst artistic ills?"

All this led the critic Ellen Willis to write in the Nation, "You don't have to be Sigmund Freud to surmise that war has a perverse appeal for the human race, nor is the attraction limited to religious fanatics committing mass murder and suicide for the greater glory of God."

The outpouring of ecstatic hope that followed 9/11 was an expression of just such perverse appeal. It was a way of channeling the taboo thrill that electrified the air after the attacks, cutting through the fog of ordinary life in a way mere movies never could. Predictions of the demise of action films were based on the flawed premise that 9/11's surfeit of sensation was altogether painful, rather than something many people couldn't bear to let go of.

Thus the falling towers were put into a kind of permanent loop after 9/11. TV retrospectives started airing while the ruins still smoked, and news outlets seized on tenuous excuses to run the graphic images just one more time, as the New York Times did in a May 26 story about those trapped in the towers during the last moments before they fell.

This isn't to criticize any specific outlet for its coverage -- after all, as New York Times deputy managing editor John Geddes said in the New Yorker, Sept. 11 was "the story we had been training all our lives for." For months afterwards, almost any other subject seemed grotesquely irrelevant. The war on terrorism is defining our era and it demands attention.

But the way the pictures of falling bodies and falling buildings are played over and over suggests a voyeuristic impulse cloaked in patriotic piety.

Compare it to the video of Daniel Pearl, which is too sickening to broadcast even once. Some would argue that the Pearl video is different because it's more personal, that the singular brutality is more easily grasped. Large numbers of casualties often become abstractions. Still, if it hurt to see the towers blow up with thousands inside, would we be compelled to watch it a thousand times?

After Sept. 11, countless commentators spoke of how cinematic the whole thing was. What no one mentioned is that "it was just like in the movies" is frequently the phrase Americans use to describe the pinnacles of experience -- a first kiss, a fairy-tale party, a trip abroad. Something that feels "like a movie" is something that has an addictive feeling of heightened reality.

Stockhausen wasn't so wrong -- in a media-glutted world, Sept. 11 couldn't help but become the ultimate reality show. So enamored were we of its rare, shocking authenticity that we replicated its image into infinity and leached it of its meaning. Of course, it still works as a rhetorical cudgel that the administration can use to suspend the Constitution and most accepted norms of international behavior, but that just underlies how hollow it's become -- it's a political device, like the Pledge of Allegiance, sanctimoniously recited on the Capitol steps.

Which brings us back to ground zero, and the visitors who treat it with the lurid, loud fascination they might accord O.J.'s old house on North Rockingham Drive.

The impulse to see places where carnage occurred is a common one. As Paul Theroux reported in his book "The Great Railway Bazaar," the South Vietnamese were planning on luring curious American travelers to famous battlegrounds while the war was still raging. Holocaust tourism is a huge phenomenon and a rite of passage for Israeli high school students. There's a gift shop at Cambodia's "killing fields."

Yet the feel of these places is simply not as empty and meaningless as the World Trade Center has become. Maybe it's because there are still bones in the killing fields, nooses hanging from trees and teeth scattered in the grass, but the presence of commerce doesn't impinge on the solemnity of the place, its aura of metaphysical horror. Only a psychopath would pose for pictures there.

And that's something that happened more than two decades ago; mere months have gone by since Sept. 11, yet already the World Trade Center site is treated like a landmark from distant history. A writer to the New York Times defended tourism at the ruins on the grounds that Americans frequently visit famous Civil War battlefields like Gettysburg and Antietam.

One great, defeated hope of the days after Sept. 11 was that the magnitude of the event would trump the process that turns distinct events -- electoral scandals and Hollywood murders, wars and blow jobs -- into solipsistic circuses. Instead, the event itself has been buried under an avalanche of examination and commemoration. It's an excuse for celebrity telethons, the subject of too many books, a subplot on prime-time TV dramas.

The self-help rhetoric of healing and closure might stipulate that this is all America's way of processing and coming to terms with the attack, but from ground zero it looks a lot like our way of sucking every last morsel of scintillation from the most exciting day many have ever known. The iconography of Sept. 11 has already metastasized into clichi, and yet people want more from it. So they go to the rubble-strewn graveyard; they snap photos and buy trinkets. It's become just another place where something famous happened, and where a few dollars will get you your very own piece of the fading drama.

Next: How will a public gravesite honor private wishes?

Shares