Settling into his chair at his cluttered desk on a Tuesday morning, Scott Kessler flicks on his computer and calls up images of injuries. A woman's face emerges, her nose outlined in purplish-blue bruises. Swollen cheeks, lacerated lips, abrasions, scratches, bruised limbs and broken capillaries fill the screen as Kessler, head of the domestic violence bureau in New York's Queens County District Attorney's Office, clicks open recent files, 15 from that morning.

He pauses before an image, pointing out a cut that scores a women's eyelid like an engraving. In another, bumps rise like a ridge from a man's forehead. Kessler zooms in on a woman's back, focusing on a red patch surrounded by black and blue. "You can see the outline of the object used -- a stick," he says. "You'll never see anything like that on a Polaroid."

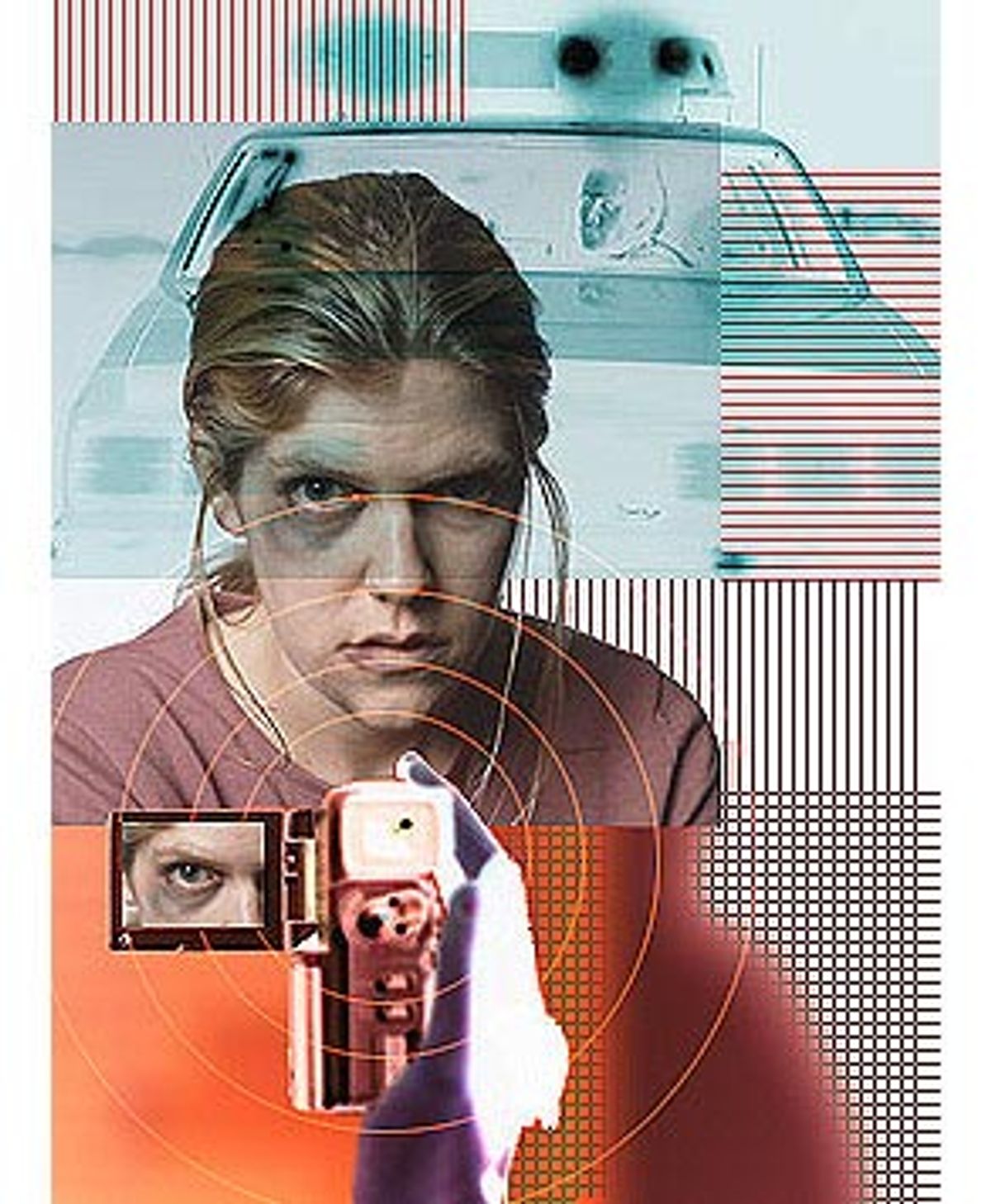

At the 112th Precinct in northern Queens, Officer Linda Rivera holds up a 1.2 megapixel Kodak DC-120 with zoom and built-in viewer. "I was a little nervous when I heard the word 'digital camera,'" she says. "But it's so basic. A victim comes in. We photograph her here or at the hospital. You press two buttons. You see the photo instantly." Before the coming of digital, "we got a lot of dark photos. We'd run out of film. It could be spoiled, discolored." Close-ups, critical for depicting wounds, required cumbersome attachments, some of which had to be fastened to the victim. "This is quicker and less invasive."

Digital imaging, used for mug shots and in fingerprint analysis for years, has edged its way into the touchy territory of domestic violence investigations. "Any agency that has used digital photography for general crime-scene photography is using it for domestic violence, with only a rare exception," says George Reis, whose company, Imaging Forensics, trains federal, state, county and city police forces throughout the country. "Think of all the agencies that have traditionally used Polaroids for domestic violence. Digital is certainly a cheaper and better way to do it."

Convenience isn't the only advantage a digital camera has over its predecessors. For example, Polaroid photographs, taken just after an assault, often fail to depict incipient bruising or the red marks that become more conspicuous in the following days.

"In the past, it was difficult for a prosecutor to convey to a court the extent of the injury, particularly where the injuries are quite serious but don't rise to the level of broken bones or teeth knocked out," says Queens District Attorney Richard Brown, whose office has stepped up its attack on domestic violence since receiving a $3 million grant under the Department of Justice's Violence Against Women Act five years ago.

"[Polaroid] pictures suffer from a number of problems," says Herbert Blitzer, executive director of the Institute for Forensic Imaging at Purdue University. "The lenses put in distortion. The images tend to be dark. It's expensive."

Although 35-millimeter cameras transcend the technical limitations of the Polaroids and might even offer better resolution than some digital models, few patrol officers have the photographic skills to handle them successfully. "They often make several mistakes, and the images are no good," says Blitzer.

"They often get too close to the subject, and so I had blurry pictures," says Timothy Johnson, deputy district attorney in the sex crimes and domestic violence unit in the Boulder (Colorado) District Attorney's Office. Six of the nine police agencies in his jurisdiction switched to digital cameras about two years ago. "In strangulation cases, which in Boulder County is a growing method of choice, the injuries didn't photograph. They overdo the flash. How do you prove strangulation if you don't have marks?"

Kessler, examining an 8-by-10-inch digital printout of a woman with a cut lip, says, "The color is better, especially for women with different complexions," a fact not lost in Queens, whose 167 nationalities make it the most ethnically diverse county in the country.

Most importantly, the photographs can be downloaded and zapped from the precinct to the prosecutor's office within minutes of an arrest, instead of days or weeks. "We can print them out and present them at arraignments," says Kessler, whose staff handles about 4,500 misdemeanor and 500 felony cases a year. "They're strong evidence in bail applications."

Whether technology can make a dent in domestic violence, a complicated nexus of behaviors that includes battering and injury, psychological intimidation and sexual assault between intimate partners, is anyone's guess. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1.3 million women and 835,000 men are physically assaulted by an intimate partner every year in the United States. Will incremental advances in technology make a real difference in those figures? And, wonder some critics, is the malleability of digital imaging a potential weakness for getting evidence accepted in court?

Police and prosecutors dismiss the possible drawbacks of the new technology. They believe that high-quality digital photographs received early in the legal labyrinth can make an impact -- especially in the complex world of domestic violence, where victims are often unwilling to testify, and pictures have to do the talking.

"There's strong evidence that they're a good tool in fighting domestic violence," says Kessler.

Queens is the first and so far the only area of New York City using digital cameras to photograph domestic violence victims. Working with the district attorney's office, the New York Police Department weaned the county's 16 police precincts off their instant Polaroids about 14 months ago, starting with three digital cameras in three precincts, then adding five more a few months later, then eight more, until every domestic violence unit in every Queens station house had one. "They were doing digital photographs of offenders. We figured if we could get documentary evidence of what an offender looked like ... we should at least be documenting what the victim looked like at the time of the crime," says Lucia Raiford, director of the NYPD's domestic violence unit, which bought the cameras.

George Reis, who is also a crime scene investigator for the Newport Beach (California) Police Department, estimates that up to a quarter of the 18,500 police departments in the United States have swapped their 35-millimeter and instant Polaroids for digitals. "Digital photography probably started in forensic applications on the West Coast and moved east," he says. His own force went digital in 1991. "You'll see it much more in agencies that are 200 people or less. It's an expensive transition for a large agency -- they have to buy so much more of everything -- and it's hard to coordinate."

David Adkins, principal photographer in charge of the Scientific Identification Division at the Los Angeles Police Department, says digital cameras encourage officers to take more photographs when out on domestic violence calls. "People are conscious of the cost of Polaroids at $1 or $1.25 apiece, and they'll take three or four and feel that's enough. They're excited about the digital technology. They know they can take as many as they want, because there's this perception that digital photography is free photography." When the perpetrator is confronted with the barrage of evidence, "a lot more plea bargains come out of it."

Digital documentation has also resulted in stiffer charges. Deputy District Attorney Johnson says he has filed more felony-level charges and more high-level third degree assault charges when he provides digital photographs. "They're supported by better evidence," he says, describing a case in which a husband knocked down his wife and strangled her into unconsciousness as her face bled. The police took 27 initial photographs, along with follow-up pictures three days later. "Her left eye was swollen shut, and her neck had inflamed to about twice its size because of the trauma," says Johnson. "Because of the digital technology, I was able to see that faster and filed a felony assault instead of a misdemeanor assault."

Prosecutors hope the digital photographs will help them sidestep one of the touchiest issues in pursuing domestic violence cases -- the victim's reluctance or refusal to file a complaint or testify, and the tendency to retract a complaint or testimony later. Sometimes it's for economic reasons if the batterer is the main wage-earner. In localities like Queens with large immigrant populations, victims might have a genuine fear of the INS. "The victim might not speak English or understand what is going on. They're not sure what's going to happen to them in court," says Rita Asen, director of Queens Criminal and Supreme Court programs for Safe Horizon, which counsels victims of crime and abuse. Often, the victim fears retaliation from the defendant or the defendant's family. "It's a tough decision for them to make," says Wanda Lucibello, chief of the special victims unit in the Kings County-Brooklyn District Attorney's Office. "The punishment is pretty minimal in a misdemeanor. We're asking women to participate in cases where there's not a big hammer hanging over the guy's head."

In these victimless, or more euphemistically, evidence-intensive prosecutions, the digital photographs become important, especially in "no-drop" jurisdictions, where prosecutors can pursue a case without the victim's consent, complaint or testimony.

"The evidence can sometimes be put together in a way that can stand on its own," says Lucibello. "Our hope is that these cases can go forward without the victim's participation when we think that's going to be the safe, sound way to go. The injuries can be documented, the scene can be documented -- the broken furniture, the door that's got the dent marks in it because somebody tried to kick it open, the table that got broken, the chair leg that might have been used to menace the victim, the doors, the tables, the blood that gets left behind. All of that is the way these cases get prosecuted without the victim."

If the photographic evidence is strong enough, the police officer who responded to the emergency call can testify for the victim. The "excited utterance" exception to the hearsay rule allows the police officer to testify about statements the victim made right after the assault if it can be proved she made them while still under duress. "We often have a difficult time because what evidence do we have other than the officer saying, she looked scared, she looked upset," says Johnson. "With the digital photography, we're getting higher-quality pictures during the interview. We're able to get pictures of the victim crying, with tears in the eyes. Getting these 'excited utterances' in is a huge victory for us in these victimless prosecutions."

One oft-mentioned criticism of digital photography is its malleability -- anything digital can be changed with ease, which raises questions about the admissibility of digital images as evidence. But despite their malleability, digital images have faced few court challenges. Federal and state rules of evidence have stretched to accommodate the technology. In the 1995 precedent-setting case of the State of Washington vs. Eric Hayden, the court admitted into evidence digital photographs of fingerprints it knew had been altered (police investigators had enhanced latent hand and fingerprints found on a bedsheet through a variety of techniques the court deemed scientifically valid -- NASA scientists had developed the technology in the 1960s to record satellite signals), and convicted Hayden of murder. The state appellate court upheld the decision three years later.

As a result, courts regularly admit digital images, even when they know they've been changed. "Just as with traditional photographic images, digital images generally need to be altered to represent what the person who photographed them saw," says Reis. "Altering an image is not necessarily a bad thing; it's a required thing in many cases."

But every new touch-up tool from Photoshop, Photo-Paint, Photo Studio and the like raises questions, provoking periodic cries to amend the "evidentiary codes."

"Digital photographs are easy to manipulate by using the clone stamp or multiple other tools," says David Spraggs, a detective with the Boulder (Colorado) Police Department, who oversaw his agency's switch to digital about two years ago.

Not everyone agrees it can be done effortlessly, though. "It's what I call the goat's head syndrome," says the LAPD's Adkins. "It's the Hollywood version and the belief that you can put a goat's head on a donkey and no one can tell the difference. Well, it's not so easy to do that. You can make those changes, but you have to work quite a long time with the right tools to do that."

Spraggs, who teaches digital forensic photography and crime scene investigation, uses Adobe Photoshop daily to sharpen, resize, adjust the color or correct for faulty focus or camera settings. Sometimes he also uses GretagMacbeth's color-gauging tools.

Color is particularly important when preparing photographs of domestic violence or assault victims, he says. "We don't want to make the injury seem worse than it is or less serious than it is. We make the images look like a more accurate representation of what the photographer saw at the scene." Spraggs saves the original images on a writable CD-ROM, makes his changes on working copies and records every step he takes to enhance the original image on Photoshop's Action Palette. He then prints and attaches the record to the photograph and sends it to court. Any investigator can replicate Spragg's changes and reproduce the photograph from the original file, just like in a scientific experiment.

Call it ethical enhancement. "The distinction is between changing the quality and changing the content," says Reis. "You never change the content."

But, as Spraggs admits, the line can at times become gray. He offers his favorite reply: Traditional film-based images, which were always retouchable, can now be altered just as easily as digital photographs. "You can scan that film into a computer, turn it into a digital file and manipulate it in Photoshop," he explains, and, with a device called a film recorder, reconvert the altered digitized files to film. "Basically, the technology goes full circle, and has gotten to the point where any image can be questioned." In other words, if film is no longer "safe," why worry about digital?

Always ready to fill a vacuum, vendors have stepped in with image-security software in the form of "tamper-proof" encoded formats that bolt in the picture at the time it's captured, but most forensics experts deem such precautions costly and unnecessary. "It gives a certain amount of comfort, but most of the software can be defeated in one way or another," says Steven B. Staggs, author of Crime Scene and Evidence Photographer's Guide and a forensic photography instructor for 17 years.

Instead, Staggs and Swaggs preach such low-tech steps as developing standard operating procedures, maintaining chains of custody for the images, preserving the original, keeping logs, restricting access -- all basic guidelines similar to those developed by the FBI's Scientific Working Group on Imaging Technologies, or SWIGIT.

"If people buy into your protocols, you're fine," says Staggs.

Courtroom acceptance of an image, whether a drawing, a conventional photograph, a videotape or a digital photograph, has hinged on "authentication," which requires only that an on-the-scene witness testify that the photograph is an accurate representation of what he or she saw. "That statement takes the onus off the means by which [the photograph] was produced and puts it on the testimony of the witness, because the witness testifies in fear of perjury," says Blitzer, who sits on the SWIGIT committee. "The technology is a backseat issue. You can't put a picture in jail, but you can put a false witness in jail."

But while the technology itself doesn't appear to be riling defense attorneys, the notion of victimless prosecution -- the idea that photographs can substitute for an unwilling plaintiff -- does raise serious hackles.

"They've tried to do it, and we scream," says Steven Silverblatt, supervising attorney for the Queens Legal Aid Society. "The defendant feels deprived of his constitutional rights when this happens. They're looking for ways to make the case without the victim. If they want to take better pictures, great. No one can say that better photography is damaging, provided they don't pressure people who don't want to press charges into doing so. People have complicated relationships. They might want to solve their problems on their own. It's not that we approve of domestic violence, but these solutions can produce results a complaining witness doesn't want."

Unlike armed robbery or other attacks by strangers, domestic violence cases "are complicated in a way that a lot of other serious crimes are not," says Holly Maguigan, a professor of clinical law at New York University who studies the criminal prosecution of domestic violence cases. "Sometimes victims don't press charges because prosecution isn't the way out of a bad situation for them. It might not be a particular woman's own best route to safety. Since the police cannot provide 'round-the-clock protection to people, there's a way in which it's hard not to credit her opinion."

Prosecutors say they stay mindful of this. "With some people, the prosecution is only part of the big picture," says Lucibello, whose office will soon be relying on digital photographs. "But you need to be ready to go forward without the victim's participation. I can think of examples where the hair would stand up on the back of your neck if you thought there wasn't going to be a prosecution. But that doesn't mean you'll always take that route -- maybe it's working with an advocate and putting together a safety plan. Even if you decide at the end that prosecution is not the safest thing to do, the digital cameras give you the ability. They're something to go into the arsenal of weapons."

Shares