Ostensibly, the big selling point of "Never Again" is that it's a love story about two people over age 50 that doesn't shy away from their sexuality. As refreshing as it is to see this kind of story up on the big screen, there's one major problem: The characters are a major pain in the ass, to each other and to us.

This isn't a function of their age -- their behavior would be just as inexcusable in kids under 30. But "Never Again" leaves you with the sneaking suspicion that we're supposed to cheer these characters on precisely because they have so many tics, that their flaws are supposed to be more charming to us precisely because of their age. We're supposed to reward them for being so resolutely themselves, regardless of whether those selves are bearable to watch on screen or not. I'm not just talking about the usual things you might see in a 50-plus character, like the fact that people get more set in their ways as they get older, which is completely natural. I'm talking about an angry 54-year-old woman screeching across a cafe table at her lover, using every stock psychobabble phrase in the book to explain to him why he's afraid of commitment. It's ugly when a 24-year-old does it; shouldn't a 54-year-old know better?

Apparently, writer and director Eric Schaeffer doesn't think so. There's a way to make us care for characters who are absolutely maddening: Nicole Holofcener does it with Catherine Keener's character, an unhappy 36-year-old mom who always says the wrong thing, in the recent "Lovely & Amazing"; an older example is the thorny, perpetually single (and lonely) young woman played by Marie Rivière in Eric Rohmer's "Summer."

But Schaeffer can't pull it off in "Never Again." His characters' eccentricities do have a bit of charm now and then (and the story is set in New York, where if you're over 50 and not at least a little eccentric, you're in the minority). But before long, these characters are so wearying to us that we wish they'd just get it together and get on with it, so we can go home. What's more, Schaeffer works hard to place them in allegedly hilarious situations that aren't so funny at all: You'll roll in the aisles when Jeffrey Tambor walks into a gay bar and insults the cowboy cutie who comes onto him! You'll bust a gut when Jill Clayburgh tries to saw off her strap-on dildo with a carving knife! And so on.

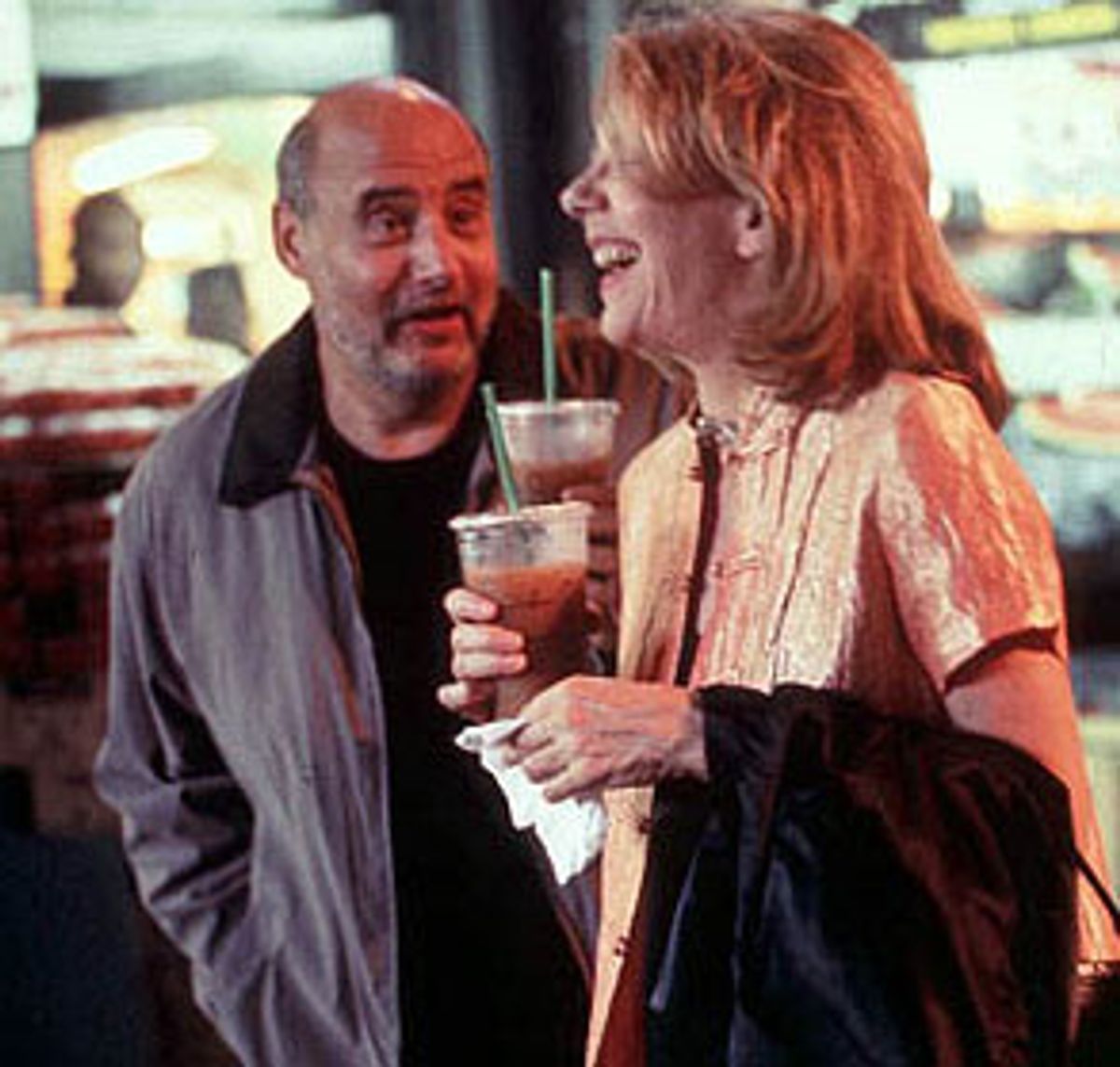

Tambor plays Christopher, a very single jazz musician who, because of a few recent sexual difficulties, has decided he just might be gay. He decides to experiment, first by making a call on one of those "chicks with dicks" who advertise all over the back of the Village Voice. When he decides the "chick" isn't to his liking (she's played by Michael McKean, of "This Is Spinal Tap," who manages to make this broadly comic character seem like a human being), he clumsily takes his leave -- doing everything but blurting out to her how ugly and repulsive he finds her -- and makes his way to a gay bar. There he meets Grace (Jill Clayburgh), who has just had a disastrous blind date with a dwarf. (Forget the fact that his face is ruggedly handsome; she can't keep giggling over his height. That's what the wisdom of age and experience will get you.)

Grace and her pals, played by Caroline Aaron and Sandy Duncan, have planned to dance the night away in a place where they won't have to worry about the behavior of straight men (especially those pesky dwarf ones). Christopher comes on to her because he thinks she's -- get this -- a chick with a dick.

He soon finds out she's not, of course, and the two begin a courtship that is at first prickly and tentative, then sweet, then solid, then rocky. We're supposed to laugh and cry along with them, but they make it awfully tough. Of the two, Tambor is much more bearable: Mostly, he makes you see that his clumsy manners are just part and parcel of his awkward, bearlike warmth. But Clayburgh is simply a trial. She's fine in her quieter moments, particularly with Tambor. But when she's proving what a well-rounded, wise, neurotic-but-so-what? 50-something she is, she's dismally shrill.

We see how the two are well suited for each other, but we're not sure we want to stick around and find out how it all comes together. And while it is something to see a movie about 50-year-olds that takes their sex lives into consideration, the movie uses up much of its goodwill by scoring some unfair points. As we listen to Grace in the beauty parlor telling her pals, in great detail and in a very loud voice, all about her sexual escapades, a much younger woman, seated under a nearby hairdryer, listens in disgust. "I'm so glad my mother doesn't talk like that," she says with a sneer. The older women jump on her: "We helped birth feminism; what's your legacy going to be -- Jell-o shots?" Aaron's character snaps.

As snotty as the young woman's comment is, you have to ask: If Clayburgh were a 24-year-old spilling explicit details of her sex life in an unavoidably loud voice, would that make it OK? Bad manners are bad manners at any age, and having been on the forefront of feminism has nothing to do with it.

But in the world of "Never Again," that doesn't matter. Christopher and Grace can be as annoying as they want, and anyone who objects is likely to get a nice little lecture that may as well begin with the words, "When I was your age, missy ..." In that amorphous, heady time we call the 1960s, the era of Christopher and Grace's youth, young people railed against their elders' droning lectures. In the stunted vision of "Never Again," the '60s kids are the ones doing the droning -- in this case, defending their right to yak about cunnilingus and fellatio loudly in a public place -- and it's the young people who are stupid and square. Love can come to us at any age; and apparently, sanctimoniousness can, too.

Shares