Sept. 11 forced Americans to engage in that most un-American of activities: thinking about the country they live in. Mass death and the prospect of a future changed permanently for the worse has a way of raising questions. Some of them were purely political: Were the attacks perpetrated by evil men whose only motive was to do evil, or did specific U.S. policies lead to the attack? Should we rethink our entire approach to foreign policy, or bring renewed fervor to it? But others were more general. What kind of country is America? What does it stand for? How does the rest of the world see it? Why would people hate it enough to deal it such a blow?

Today, almost a year after the attacks, whatever illumination those ruminations provided seems faint indeed, buried beneath a ton of stale emotions and accumulated banalities, the dreary aftermath of a rending event that has no resolution. For a moment, the terrible collapse of the towers seemed to promise, if not a reborn America -- those portentous claims that "nothing will ever be the same again" now seem vaguely embarrassing -- at least one that its citizens would see in a new, sharply defined light, the way a person diagnosed with cancer suddenly sees his life strange, whole and infinitely precious. For a few weeks, a visceral sense of unity, a forged purpose born of a shared wound, allowed all Americans, the secular and the devout, liberals and conservatives, the ironists on the coasts and the straight shooters in the heartland, to come together under a flag that for once meant the same thing to everyone. But that sense of purpose, that clarifying vision, is gone. One of the most difficult of the many painful lessons of tragedy is that even its gifts do not always stay.

Many of those who wrote about America in the immediate aftermath of Sept. 11 fell into two predictable categories: the self-lacerating leftists and the breast-beating patriots. Those in the former camp displayed the virtues of sober reflection, but at times they seemed too worldly, too unsentimental, too quick to show off their cool awareness that much of the rest of the world has suffered far more than the United States ever has and that America has been directly or indirectly responsible for a great deal of that suffering. They were, of course, right, but their calculus lacked both empathy and a sense of historical proportion. Too much deference to history is vitiating: Not only does it leave one unable to strike out instinctively at danger, in the end it leaves one unable to feel anything at all. Patriotism has a tincture of sentimentality in it, but so do all feelings that have cooled into reflection, feelings that can support promises -- and these are the feelings that allow work to be done and civilization to be built.

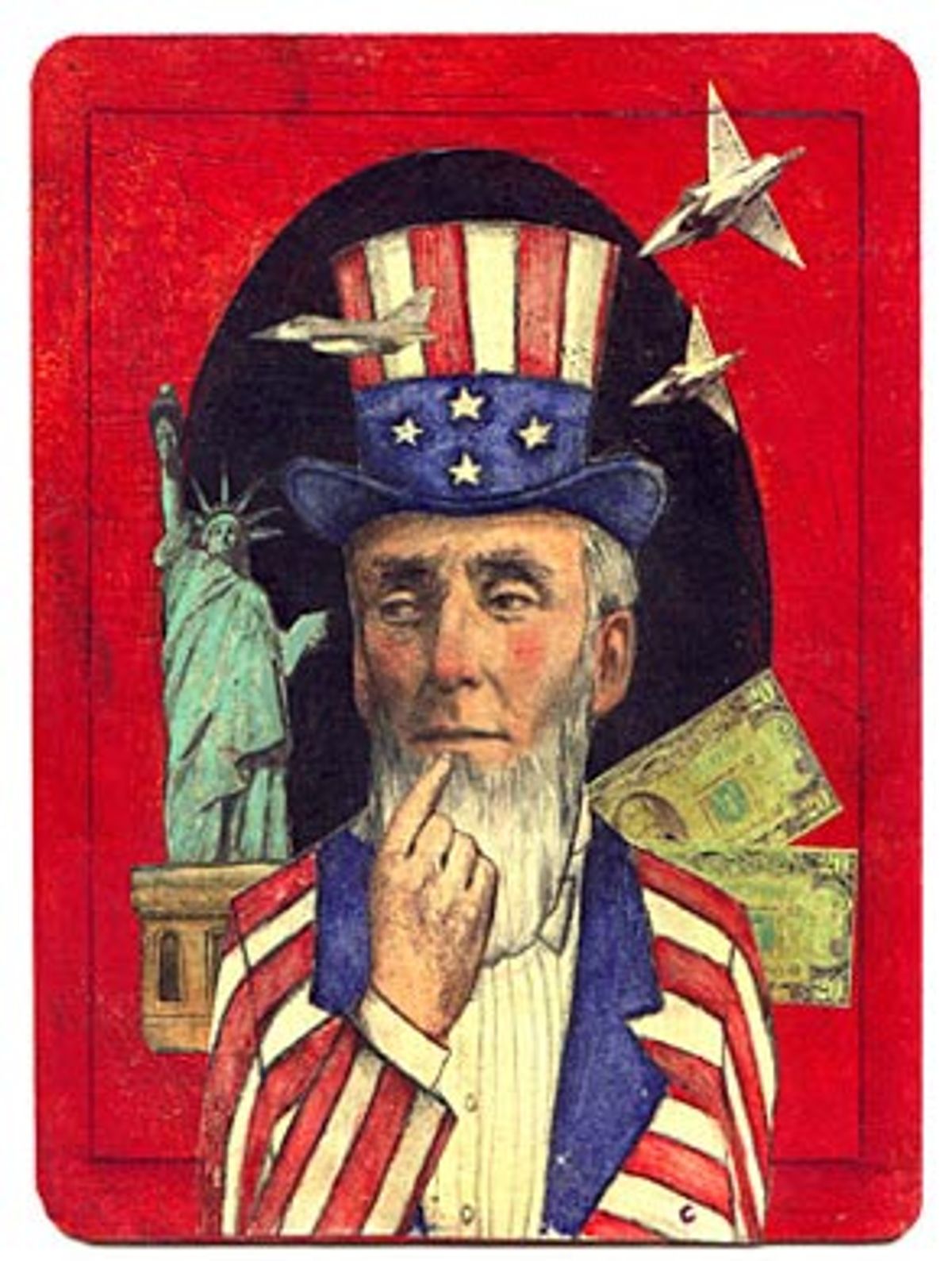

By contrast, the patriots were full of laudable vigor, but they were often myopic in their own way, unable or unwilling to grasp that even the worst tragedies do not relieve one of the responsibility of thinking. All too often, they reacted with outrage to even modest suggestions that it might be wise to consider whether any American actions might have led to the attacks, and that a little reflection on our place in the world might be in order. At their best, the patriots recalled the passionate but woolly-headed Mitya in "The Brothers Karamazov"; at their worst, they came across as nativists wrapped in the red, white and blue of permanent outrage, bludgeoning those who did not share their relentless Americanism.

Between or beyond these two essentially political poles, the rest of us wandered uneasily, sensing that both visions contained elements of truth but that neither did justice to who we are or the place we live. The fallout of Sept. 11 brought no closure. America's retribution, the attack on the Taliban and al-Qaida, was both inevitable and necessary, the clearest manifestation of American power as self-defense since World War II, but it did not bring catharsis or clarify America's identity to its citizens. In fact, this is encouraging: Wars should not do those things, and the temptation to make them into metaphors must be resisted.

President Bush did not resist. He framed the attack as an attack of evildoers against the chosen people, an act of sheer perverse malice, like Satan striking out at the angels in Heaven -- an effusion of rhetoric as empty as a discontinued greeting card. It is true that Bush and his lieutenants have a responsibility to hunt down those responsible and prevent more such attacks, but they have gone much further. To a degree surprising only to those who thought Bush the younger might have a more nuanced view of the world and not be a cat's paw for the old Cold Warriors he is surrounded by, the Bush administration has used the purposely vague and open-ended "war on terrorism" to advance its ideological and political agenda and intimidate dissenting voices. For those Americans opposed to the administration's arrogant unilateralism and simplistic worldview, this failure to learn from a national tragedy is immensely disappointing, and the manipulation of that tragedy feels like a cynical defilement.

Perhaps irrationally, we wanted to come away from the tragedy of Sept. 11 with something beyond politics and righteousness, something closer to the sense of this vast reckless lovable coldblooded hard-working extravaganza of a country that can be found in the short obituaries for the World Trade Center victims in the New York Times or the poems of Whitman or the songs of Chuck Berry -- meaningless sharp truths illuminating the American night. We wanted some kind of conclusion with long enough arms to fold all of us in. We wanted something that would get the bad taste of soapbox moralizing out of our mouths and leave the dead in peace.

One way to make a start, in thinking about America, is to examine what people who are not from here think about her. There are times, perhaps, when the only way to find out who you are is to look at yourself through other eyes.

The spring issue of the quarterly literary journal Granta gives readers a chance to do just that. Titled "What We Think of America," it offers 24 short pieces by foreign writers (with the inexplicable inclusion of one writer from Hawaii), who deal with subjects ranging from a Lebanese woman's painful realization that the U.S. can be even more heartless than her native land, to a British writer's revelatory experience of the unique intensity of American literature, to the Hollywood censorship that led an Indian youth weary of truncated blouse-unbuttonings to prefer Russian films, to an Irishman's confession that America no longer seemed strange because his own country had become America. By turns intimate and broadly analytical, these pieces are idiosyncratic, penetrating and refreshingly free of Big Thoughts about Sept. 11. Above all, they evince (almost all of them, anyway) a generosity of spirit, a clear-eyed affection for America -- despite its flaws -- and Americans. Those of us who can no longer even hear the braying self-praise of our compatriots will find this collection both touching and enlightening.

That intelligent foreigners have such deep and positive feelings about America, that they are willing to go past the received notion of America as a naive, blundering or perhaps malevolent giant, may come as a surprise. Being kicked when you're down is a memorable experience, and certain pieces written after Sept. 11, as well as a steady flow of news stories along the lines of "Parisian intellectuals change mind after 24 hours, deny that vacuous Americans are worthy of empathy," confirmed for many that the foreign intelligentsia took a jaundiced view of America -- or actively despised her. The most notorious such piece, widely disseminated on the Internet, was by the Indian novelist Arundhati Roy. Titled "The Algebra of Infinite Justice," it danced around the notion that America deserved the attack for its foreign-policy sins, and concluded that there was little difference between Osama bin Laden and George W. Bush. "Both are dangerously armed -- one with the nuclear arsenal of the obscenely powerful, the other with the incandescent, destructive power of the utterly hopeless," Roy wrote. "The fireball and the ice pick. The bludgeon and the axe. The important thing to keep in mind is that neither is an acceptable alternative to the other."

This is not mature political thinking: It is name-calling, and it descends from a specious platform of perfect Third World rectitude. The limitations of Roy's analysis are revealed not by her unassailable assertion that America has committed sins, but her monolithic insistence that all of America's foreign-policy interventions are pernicious and all of them can be explained by the basest and most self-interested of motivations. This argument is so selective and tendentious that it betrays what one suspects is an underlying hostility that precedes political analysis, a hostility created by the mere fact of America's global preeminence.

Of all the fears Americans have about what others think about us, probably the deepest -- and the one we can do least about -- is that they hate us simply because of how much power we have. But on this subject, as so many others, many of the authors in "What We Think About America" hold surprising views. One of the revelations of this collection is that although foreigners are aware of America's power and influence, and of course of its shortcomings, they are far more aware of its complexity, its strengths, its paradoxes than we think. They are also closer to us, more attuned to the American sensibility than is generally believed. This awareness, and closeness, leads the writers not just to reject or slavishly imitate the "dominant power," but to engage with it in much more interesting ways.

For the Australian writer David Malouf, it leads to a nuanced perspective. "We are ambivalent about 'America' -- but isn't that so with all of us, even a good many Americans? -- according to what America most immediately suggests to us: The United Fruit Company, McCarthyism, Vietnam, the CIA subversion of Allende, the tanks at Waco; or the words of the Declaration and Lincoln's address at Gettysburg, the Marshall plan, the Civil Rights Movement, our own delivery from European Fascism, Communism or the Japanese."

For the Irish writer Fintan O'Toole, America is so omnipresent that it has ceased to be an Other altogether and has totally taken over his own country. What's noteworthy is that O'Toole doesn't write about this mournfully, but with a kind of nonjudgmental sense of wonder: "We had broken America's spell by turning it into our own, living it out day by day ... And if we sometimes feel the tectonic plates shifting beneath us and wonder where we are, it is simply because America is now the ground on which we stand."

The German writer Hans Magnus Enzensberger, on the other hand, argues that America has not taken over Europe at all, that Europe has become more European and the U.S. more American, and this is a good thing. The strangeness of America, for Enzensberger, leaves it wonderfully unknowable: "Surely we cannot pretend to understand such a society entirely. It will always be something else, a world unto itself, a Western Heavenly Empire, a China of our imagination, a place to admire, to be grateful to, and to be baffled by forever."

The British writer John Gray echoes the notion that the United States is fundamentally unknowable, but he puts a less Romantic gloss on this fact than the German. After citing such stereotype-busters as Dorothy Parker and H.L. Mencken, who flourished in a culture supposedly without irony, Gray writes, "America is too rich in contradictions for any definition of it to be possible ... In truth, there is no such thing as an essentially American world view -- any more than there is an essentially American landscape. Anyone who thinks otherwise shows that they have not grasped the most important fact about America, which is that it is unknowable." After commenting -- movingly, to an American -- that Americans responded to the tragedy of Sept. 11 with dignity and conducted the war with restraint, he concludes that a new United States, broader and more enlightened and no longer certain that its values will conquer the world, is "being born -- one as creative, contradictory and indefinable as any that has existed in the past." Whether this optimistic prediction will come true, in the age of Bush, seems doubtful from this side of the pond; but perhaps the long, external view is the better one.

For the British/Dutch/German writer Ian Buruma, America's omnipresence makes the actual country vie, in the imagination of the world, with "America," a make-believe place as seductive, addictive and illusory as Gatsby's green light: "The pull to cut loose, to reinvent ourselves, to shake off the past, and to want instant gratification, sexual, material, spiritual, is something most of us have felt. That is why 'America,' the ideal, expressed in Hollywood movies, rock music, advertising and other pop culture, is so attractive, so sexy and, to some, so deeply disturbing. All of us want a bit of 'America,' but few of us can have it, and even those who do still hunger for more, and more."

Buruma notes that he treasures the idea of America as a "possible refuge," even though he is well aware of its faults -- "the sentimentality, the conformity, the insularity." He concludes: "America, however, is a very different place to those who live in places where 'America' is only a mirage, a kind of guilty wet dream in dry desert lands, a promise which can never be fulfilled. If you live under a tyranny, with no personal freedom and no hope of advancement, in a country that feels abandoned and perhaps even betrayed by the modern world, the pull of family tribe and tradition may be all that is left. Then a very different utopia beckons the embittered pilgrim, one built on a mirage of purity, sacred community and self-sacrifice. In such a state of mind, it is not enough to avert your gaze from those seductive towers of Babylon. You might have to tear them down."

As is clear from the above passages, the contributors are struck by the strange dualities of American life, dualities that seem to them sharper and odder than those in their own lands. (Since Americans tend to be struck by the same odd contradictions in foreign lands, this may be a universal reaction to the Other.) The Indian writer Amit Chaudhuri notes that Bombay carries echoes of American culture, the same "mixture of the childlike and the grown-up, of naivete and ruthlessness, a mixture that, as I now know, is also peculiarly American." The way that American innocence and optimism coexists blandly with corruption or self-interest is a constant theme.

Again and again, the writers hammer away on the disparity between the sophistication of Americans and the crude conservatism of their leaders and their nation's international policies. The British writer James Hamilton-Paterson, who also notes that Americans are singularly ignorant of the rest of the world (another familiar theme) writes, "Time and again I'm struck by the extraordinary disparity between the United States' global face and the many individual Americans I know and love. Their sophistication, generosity of spirit, intellectual honesty and subversive humor seem wholly at odds with their country's monolithic weight on the world. Why is it, I wonder, their government is never represented by people like themselves? ... Are my friends in some way disenfranchised: part of a vital, intelligent, and quintessentially American constituency doomed to be forever unrepresented in their Congress and Senate? And if so, why?" For Americans who have essentially given up even dreaming that their politicians might reflect them, this question is painful.

Lest the reader think that the world's intelligentsia is uniformly gracious toward the United States, there is Harold Pinter, who makes Noam Chomsky look like Rush Limbaugh. The British playwright and activist whispers these sweet nothings in America's ear: "Arrogant, indifferent, contemptuous of International Law, both dismissive and manipulative of the United Nations: this is now the most dangerous power the world has ever known -- the authentic 'rogue state,' but a 'rogue state' of colossal military and economic might ... These remarks seem to me even more valid than when I made them on Sept. 10. The 'rogue state' has -- without thought, without pause for reflection, without a moment of doubt, let alone shame -- confirmed that it is a fully-fledged, award-winning, gold-plated monster. It has effectively declared war on the world. It knows only one language -- bombs and death." The most dangerous rogue state ever? Adolf, Caligula -- eat your hearts out! Mr. Pinter seems to have written one too many strange, elliptical scenes in which banal fragments of dialogue hang menacingly at cross-purposes -- and gone completely off the deep end.

The British author Doris Lessing, not as over the top as Pinter but more critical of the U.S. than many other contributors, notes in the Tocquevillean vein that "America ... has as little resistance to an idea or a mass emotion as isolated communities have to measles and whooping cough. From outside, it is as if you are watching one violent storm after another sweep across a landscape of extremes." After denouncing political correctness, which she finds run amok here, Lessing comments acerbically on the "patriotic fever" that has gripped the country after Sept. 11, leading Americans to see themselves "as unique, alone, misunderstood, beleaguered, and they see any criticism as treachery. The judgement 'they had it coming,' so angrily resented, is perhaps misunderstood. What people felt was that Americans had at last learned that they are like everyone else ... They say themselves that they have been expelled from their Eden. How strange they should ever have had a right to one."

The only global area where specific U.S. policies are explicitly discussed is the Middle East. The contributors take unsurprising positions. Haim Chertok, who was born in the U.S. and emigrated to Israel after becoming disillusioned with the Vietnam War, only to suddenly find himself serving in Lebanon, describes himself as an "unrepentant citizen of both the Zionist Entity and the global Gulliver-state," who accordingly gets the "automatic double-whammy of reproach and contempt." Although he acknowledges some Israeli responsibility for the region's suffering, he offers the U.S. unstinting praise for its support of Israel: "only American administrations have seriously endeavored to nudge Palestinians from their skewed sense of the realities of our region."

Raja Shehadeh, a Palestinian, takes a different view of the American role in the region. After pointing out that more people from Ramallah now live in America than in Ramallah, he offers an eloquent account of how the new American-financed roads to the settlements in the West Bank have "done a kind of spiritual damage. Gone is that attractive stretch of serpentine road that meandered downhill into the lower wadi that led into Nablus." He concludes by describing how his cousin was attending a wedding when the building next door was destroyed by an Israeli-piloted, American-built F-16, shattering the event and encrusting the wedding cake with glass. His cousin had studied in the U.S. and did not hate it, but when Shehadeh asked him what he thought of the U.S. he dismissed it as "a lackey of Israel, giving it unlimited military assistance and never censoring its use of US weaponry against innocent civilians." But Shehadeh ends on a poignantly hopeful note: "Most Americans may never know why my cousin turned his back on their country. But in America the parts are larger than the whole. It is still possible that the optimism, energy and opposition of Americans in their diversity may yet turn the tide and make America listen."

The Egyptian writer Ahdaf Soueif advances the theory that the U.S. affinity with Israel has a deeper explanation than the power of the Zionist lobby or guilt over the Holocaust. "The U.S. too is a (relatively) young nation; a state that came into being at the hands of groups of white Europeans who 'discovered' a land and 'settled' it -- never mind that there were people already there. Maybe America's fondness for Israel is like that of a parent watching a child follow in its footsteps. And now it looks as though the parent will be taught by the child: airborne attacks on civilian populations, illegal detentions, use of torture in interrogation, targeted assassinations worldwide: these have been the stock-in-trade of the Israeli state for fifty years and now America looks to follow suit ... I still love my American friends; like the music and stories that captivated me all those years ago they're smart and funny and open and warm. Is it really the case that to be good for them America has to be bad for the rest of us?"

Such explicitly political statements are the exception, however, and offbeat and personal observations are the rule, like Ivan Klíma's recollection of the generosity of American strangers when his car got stuck in a snowstorm ("I don't think drivers in our country would behave with such concern and self-sacrifice") or the Chinese writer Lu Gusun's account of turning on a light switch in Berkeley and discovering a poster of Ronald Reagan naked adorned the wall and that his professor friend had put the switch over his private parts. These quirky tales can be not just amusing but illuminating: the Indian writer Ramachandra Guha describes how his anti-Americanism was shaken by the sight of the dean of his college at Yale carrying a box of papers up three flights of stairs into his office -- something that would be inconceivable for his father or grandfather, who would use flunkies to carry even a tiny file. "Over the years, I have often been struck by the dignity of labor in America," he notes. But he then goes on to denounce America's woeful role in world politics, cataloging the long list of treaties -- on global climate change, biodiversity, land mines -- it has refused to honor. "The truth about America is that it is at once deeply democratic and instinctively imperialist. This curious coexistence of contrary values is certainly exceptional in the history of the world."

No collection of foreign writings on the United States would be complete without including the French, known far and wide for their Cartesian contempt for sundry American vulgarities (not to mention the wall-eyed Sartrean sneer they direct at our buttoned-up sexual behavior). But Benoît Duteurtre is far too civilized to indulge in the crass America-baiting his countrymen are legendary for. He makes the deflating point that French criticism of the U.S. allows those who make it to pretend they're not part of the same morally ambiguous world, one "mired in identical contradictions." He takes a shot at the odd, anomalous fact that contemporary French nationalism comes from the left: "They're not fighting for the French flag but for humanist values which apparently French society alone can defend (even when reality proves the opposite). Most hurtfully of all, he rates Parisians lower than New Yorkers on the self-criticism scale: He writes that when he travels to New York, "I more often come across New Yorkers able to criticize a certain kind of American horror than Parisians capable of defining a particular French horror: that mixture of a pristine conscience always ready to criticize and an unquestioning acceptance of the need to adapt and modernize. This abhorrence strikes me as particularly abhorrent since Sept. 11."

Duteurtre concludes that he found the "collapse of the twin towers more moving than any of the other tragedies of the last decade. Because in my eyes Europe and America are intimately linked by history, by way of life and thought; and because we belong to the same society which we should learn to transform together."

Of all the contributors, the one who offers the most heartfelt praise for America -- what it could be, what it is, the dreams enshrined in its most soaring language -- is the Canadian writer Michael Ignatieff. He marched against Nixon and the Vietnam war, he writes, but he believed in the U.S. in a way he never did in Canada. Citing Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural ("with malice toward none ..."), the words spoken by a rabbi in Iwo Jima burying his marines ("Too much blood has gone into this soil for it to lie barren ...") and Martin Luther King's speech on the steps of the courthouse in Montgomery, Ala. ("How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever ... Be jubilant my feet. Our God is marching on"), Ignatieff writes that the "power of American scripture lies in [the] constant process of democratic reinvention. First a wartime president, then a battlefield rabbi, then a black pastor -- all reach into the same treasure house of language, at once sacred and profane, to renew the faith of the only country on earth that believes in itself in this way, the only country whose citizenship is an act of faith, the only country whose promises to itself continue to command the faith of people like me, who are not its citizens."

For those of us who are privileged -- and yes, sometimes cursed -- to call America home, remembering those promises, and trying to keep them, is a worthy task.

Shares