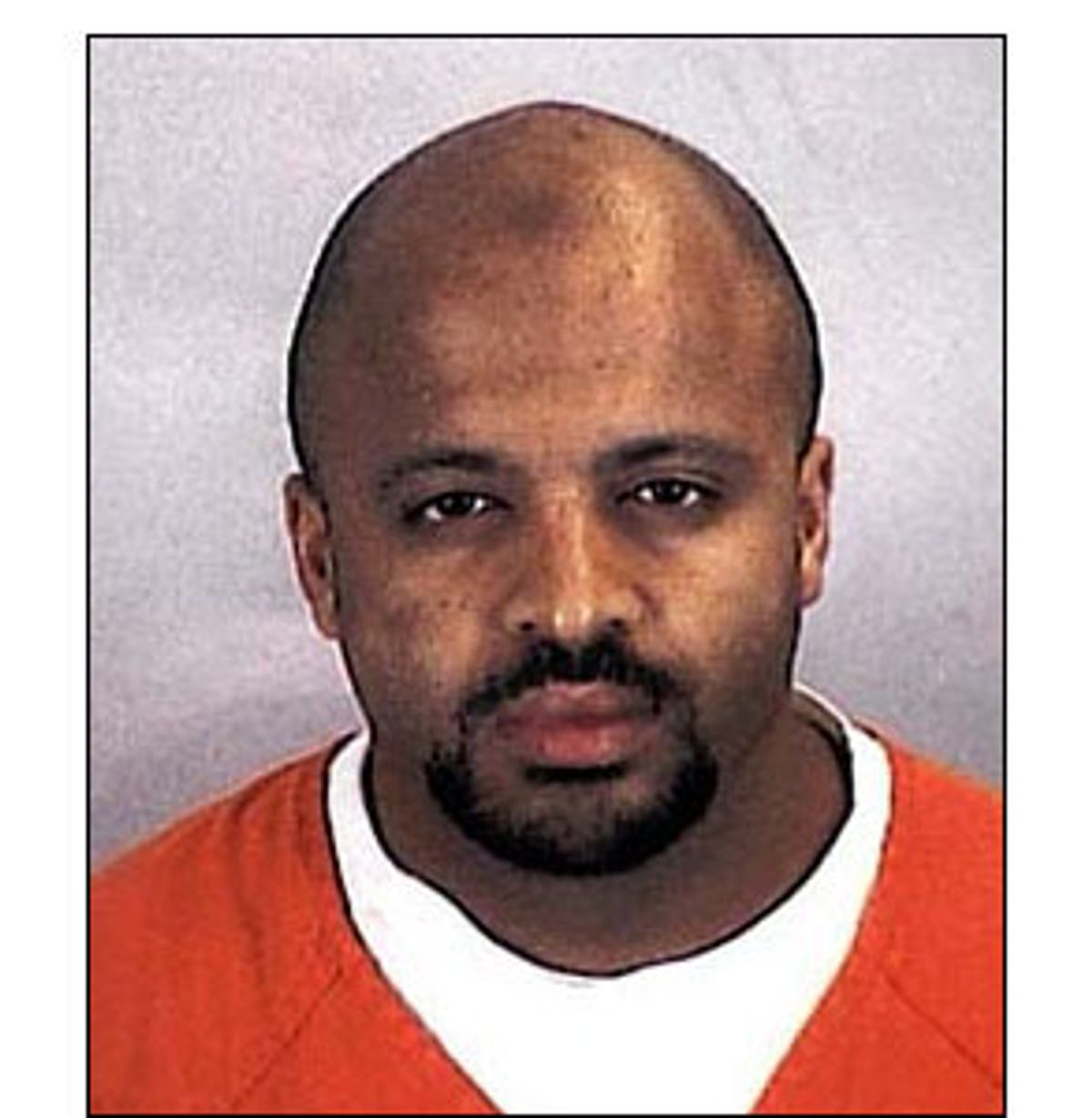

It is hard to feel much sympathy for Zacarias Moussaoui, and harder still to come to his defense. He is by his own courtroom declaration an adherent of al-Qaida and a follower of Osama bin Laden. According to the Justice Department, he attended an American flight school with nothing but ill intent.

Yet Thursday's pretrial hearing in the Moussaoui case -- in which Moussaoui tried to plead guilty to certain parts of the case, then abruptly withdrew his plea -- ought to alarm anyone who cares about credible justice in the Sept. 11 attacks. Moussaoui's weeks of erratic self-defense, his alternation between a reasonable interpretation of the government's determination to execute him and elaborately paranoid accusations against the judge and his own former defense attorneys, all call into serious question his competence to represent himself as Judge Leonie Brinkema has so far permitted. They also raise serious doubt about the attempt of the government to portray him as the "20th hijacker" and a death-row stand-in for the Sept. 11 conspirators.

Moussaoui would be a challenge for any judge. On the one hand, he seems to have a certain grasp of the facts of his case. Judge Brinkema noted yesterday that after she admonished him a week ago for drowning her office in motions and letters, he stopped -- evidence, she said, of his bottom-line competence. He was examined by a court-appointed psychiatrist and found competent to represent himself, after he fired his attorneys. Part of his presentation Thursday made a certain kind of sense. He hinted that he might have provided a "safe house" and "training" to some of the Sept. 11 crew, but had no knowledge of their actual plans. He made it clear that he wants to spare himself a death sentence by appealing to the rational side of a jury, even though he regards all Americans as an "enemy."

But alongside such moments of clarity have been many more examples of a mind both more disturbed than may appear on the surface, and certainly inadequate to the high challenge of representing himself with a death sentence on the line. He has persistently accused the court of being in league with the FBI to kill him. He won't answer letters from his former lawyers in the public defenders' office, who remain on "standby" status and continue to argue that he should not be allowed to represent himself. His motions find elaborate conspiratorial patterns in the initials of government agencies, the name of the judge and other "data" -- the kind of delusions portrayed in "A Beautiful Mind." Even yesterday, it was clear that on a base level he did not understand the meaning of a plea, let alone how to plea-bargain on his own behalf.

Why should any of this matter? For one thing, most Americans would agree that any individual operating outside the boundaries of sane judgment shouldn't be allowed to represent himself in a death penalty case -- even one involving Sept. 11. What's more, Moussaoui shows all the signs of the kind of narrow but deep mental illness that if indulged -- as Judge Brinkema so far has -- can turn court proceedings upside down.

More than anything, Moussaoui's courtroom behavior is reminiscent of the courtroom antics of Colin Ferguson, the notorious Long Island Railroad shooter. Ferguson, you'll recall, convinced a New York judge that he should be permitted to fire his lawyers and represent himself. His "defense" consisted of promulgating paranoid race theories, badgering witnesses and survivors, ducking and weaving before the witness stand and generally turning his trial into a circus. And Ferguson, it must be said, was F. Lee Bailey compared with Moussaoui, who judging from his statements hasn't the slightest understanding of how a courtroom works.

Ferguson and Moussaoui seem to have in common the kind of disturbed mental state that disguises deep paranoid delusions behind a seeming ability to grasp day-to-day facts. Moussaoui, like Ferguson, understands 2 plus 2 -- but his writings suggest a mind in which 2 plus 2 equals 5, not a formula for any kind of credible outcome in so fraught a case. It's possible that he's just playing crazy -- crazy like a fox -- but his behavior is so erratic, with flashes of lucidity, that the possibility seems increasingly unlikely.

Certainly the victims of Sept. 11 deserve better than a trial being driven by a defendant's delusions. And frankly, so does Moussaoui. It's still possible that Moussaoui is not the "20th hijacker" the government says he is. Already the prosecution has withdrawn the claim that he was interested in crop-dusting airplanes. While the Justice Department's death-penalty indictment accuses him of participation in the deaths at the World Trade Center and Pentagon, there is no evidence so far that directly links him to the Sept. 11 conspiracy.

While members of that conspiracy were carefully and discreetly learning to fly commercial jets, Moussaoui was taking lessons on a Cessna, drawing attention with his bizarre and indiscreet statements. It's hard to imagine the tight, deliberate Hamburg terrorist cell risking its "martyrdom operation" on such an incoherent and weak character. It's possible he attached himself to them anyway. It may well turn out that he was simply a hanger-on, a troubled personality who attached himself to al-Qaida and provided a U.S. contact to the conspirators with no further involvement. It may turn out that he was part of a different scheme altogether. Whatever the story, there is plenty of reason to think that John Ashcroft's Justice Department "overcharged" Moussaoui to get a death-penalty-friendly jury -- jurors who say they'll award the death penalty tend to be more conservative and pro-prosecution, on all issues, than those who won't -- and secure a quick conviction.

But there's a risk to imposing a death sentence under such circumstances. Part of the risk is of turning a marginal and mentally ill bumbler into a martyr, the inspiration for future suicide bombers. If Moussaoui is al-Qaida, better he should be consigned to the anonymity of the federal prison system than be allowed to turn his own trial into a martyrdom operation. And if he is not, we need to know that.

It's also important to demonstrate that American courts will not run roughshod over a clearly disturbed defendant, even in a terrorism case. This matters to our allies in Europe, to France in particular. Already, Europe is refusing to extradite al-Qaida suspects if they might face capital charges. France is alarmed at the prospect of its citizen facing a death sentence. The express-train conviction of an incompetent Moussaoui will anger many Europeans, while a sensible resolution of Moussaoui's case -- either returning him to the protection of his attorneys, or a genuine plea-bargain that secures his testimony and saves his life -- will demonstrate the capacity of American courts to deliver justice even under the most emotional circumstances.

Brinkema can at least partly short-circuit this coming courtroom catastrophe by withdrawing her permission for Moussaoui to represent himself. Yesterday, she reaffirmed her decision, but she may still change her mind. It is also hard to imagine that experienced federal prosecutors are looking forward to trying Moussaoui, given the careening course of his pretrial hearings. But it is Ashcroft and the White House, not those career prosecutors, who are driving the car on the Moussaoui case. Several times in recent months, an overzealous and overheated attorney general has embarrassed and infuriated the White House and even damaged the administration's conservative base in Congress. The spectacle of Moussaoui's delusions and ignorance driving the only Sept. 11 prosecution ought to cause the administration to seek a reasonable and reasoned plea bargain that ensures Moussaoui legal representation, removes the death penalty from the table, gains his participation in the ongoing al-Qaida investigation, and convicts him of whatever he really did -- rather than seeking a Sept. 11 scapegoat at any cost.

Shares