April 5, 1978

Joey Sweeney is 6 years old. His parents are divorced. This is the '70s, so lots of people's parents are getting divorced. For some people, this will mean that they go through the rest of their lives pushing and pulling with those they can find that will love them; for others, it will make them hypersensitive to the complex web of human relations that result after one person stops loving another. And it's no secret: These people will inevitably be drawn in by the emotional movie montages that are the stuff of pop and rock music.

Even at 6 years old, Joey Sweeney sees the power in this: You can use music in your brain to make all the awful things that are happening to you somehow romantic and character-building and, better than all of this, cool in a way that will, one day at least, show up all the kids who, even this early on, are calling you a faggot and a sissy. Through this rock music, thinks Sweeney, you will show them. It will add a romantic dimension to your life by making it explode with light and music; it will add layers to what is now bare. It will cover things up. It will make boo-boo better.

In the service of this, while his mother is working as a nurse assistant and his father is off God knows where, he spends his time in his grandmother's musty basement where his two aunts -- 14 and 16, respectively, and really young enough to be his sisters -- have been equipped with a cheap record player, hand-me-down hippie tapestry and all kinds of girly stuff that is still a crazy mystery to him. (Such a wacky age range of aunts, moms and grandmoms, he will find out later, is a strange blessing when compared to the rest of middle-class America, but for now, Sweeney doesn't know that, having landed from space in the white ghetto of Philadelphia where he is 6 and his mother is 22.)

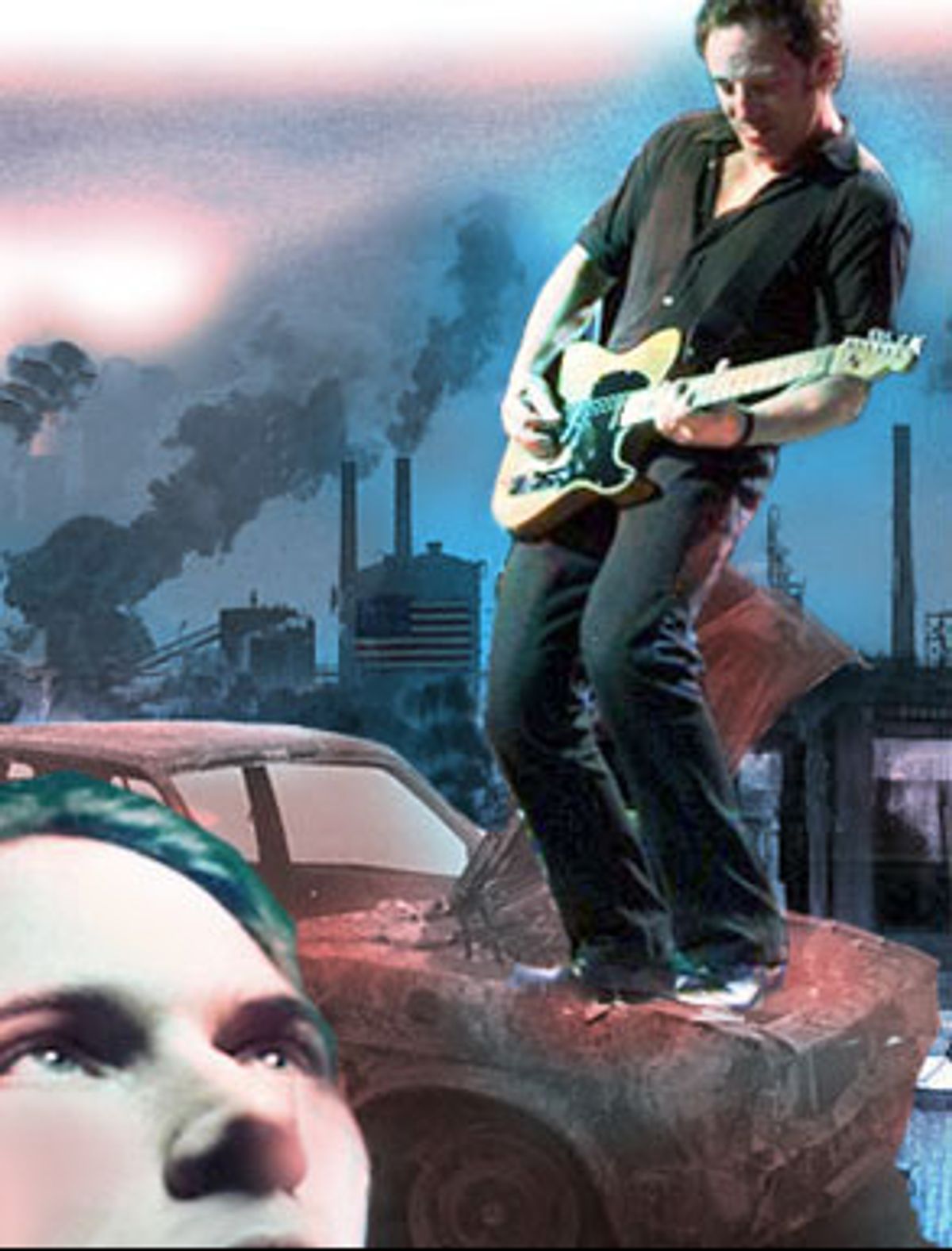

Among the records that get played down there as a soundtrack to the girls' primping and strange, codified innuendo that is totally over his head, sometimes even now, is "Born to Run," the breakthrough 1975 album by Bruce Springsteen. And though Sweeney doesn't realize it now, "Born to Run" is as much a part of the aunts as the aunts are a part of "Born to Run": Sandra and Lisa Tuno hang out on the same corner every night. They wear white high-top Converse, make out with boys and get in fistfights with other girls. It is only a matter of months -- 18, 36, whatever -- before one of them has a child of her own.

Whether they know this or not, they've taken Joey under their wing, letting him fall asleep at their secret beer parties, sing with them into a hairbrush and say funny things for them in his pipsqueak voice that will not be going anywhere, up or down, for quite a while. In return, he is allowed to wear Lisa's black-and-white baseball jersey that is silk-screened with the cover art for Springsteen's first album, "Greetings From Asbury Park."

Feb. 25, 1981

Monica from Salmon Street is my babysitter, and although I do not have the words for it in the winter of 1981, I am in love with her. She talks to me like a human being, allows me to curse mildly and watch television right up until I fall asleep. She has also introduced me to the college radio station that plays music that I do not exactly understand. Monica has noticed early on that I am almost helplessly drawn to pop music and as it turns out, she is too. Together, we watch "Solid Gold" and regale each other with stories about this new thing called MTV, which we have seen in glimpses at distant relatives' homes but will not really be able to watch for at least seven more years. For this is Philadelphia in the early '80s, and a deadlocked, lazy union and a string of ever more ineffectual mayors has prevented the entire city from getting cable TV -- a cultural shortcoming that will dog us as a city for most of the decade and arguably even beyond.

With cable -- and the electric music it transports -- an ever-more distant hope, our only contact with the rock 'n' roll world is through magazines (which, as a 9-year-old, I can neither afford nor find) and the rock radio monster that is WMMR. In the pallid wasteland of early '80s mainstream rock, there are few choices -- especially in a working-class town like Philly that, in a very self-conscious way, almost immediately (and wrongly) associated punk and new wave with clueless rich kids, homosexuals and college students, three species of people who could not possibly be farther away from the intellectual and spiritual short-stack world view of Fishtown.

All of this is to say that, in 1981, Bruce Springsteen still reigns supreme as the past, present and future of rock 'n' roll to all Philadelphians who fall under his stoned and beautiful FM gaze. To so many of us, the man is rock 'n' roll, and the local media make no secret about desperately wanting to claim him as our own; for every time he brought the house down at the Stone Pony in Jersey, the next night, he was probably playing some place down here in Philly, where everyone knows at least someone who saw him play for five hours straight before sending the crowd home in ecstatic exhaustion, each adrenal gland drained of its last ampoule of sick rock throttle.

Springsteen is a local shaman -- even Monica tells a story of her girlfriend driving up I-95 one day, only to be accosted by a van containing Bruce (bearded, rasta-cap era) and his boys, asking her if she'd like to pull over and take some "tea" with them. From Monica, I infer that "tea" is some sort of drug, although it feels lame to ask what exactly it is, and instead I concoct in my head some substance that falls somewhere among pot, hash, heroin and red wine. By the time I reach my 20s, I subconsciously will try to uncover this mystery drug every weekend, always falling short of the sweet, languid high I can only imagine Monica's friend enjoying before committing to a lifetime of servitude to the memory of that very thing.

It is under these circumstances and myths that the spirit of Bruce Springsteen will visit me again, when Monica, for whatever reasons, convinces me to trade her my copy of Tom Petty's "Hard Promises" for two albums from her collection: the Cars' "Candy-O" (I know that I'm supposed to be aroused by the redhead on the cover, having already spied my stepfather's Playboys) and "Darkness on the Edge of Town," by Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. "Darkness" strikes me as strange and off-balance even at 9 years old, and even though I don't have the intellectual equipment in place to tell you why that is, I still can't deny that it's oddly compelling.

At first -- and for a long while afterward -- I think that I got gypped in the trade. After all, Monica got my Petty album that had "The Waiting" on it, as well as "Nightwatchman." But the more I stare at Bruce on the cover of "Darkness," blank and clearly wounded at some kitchen door or other, the more something dark and truthful in myself stares back. The look he's wearing is the same one that both my folks and I have on the morning after there's been a big fight, a look that says, I am standing by the kitchen door in disbelief at the way love has failed us. I am threatening to leave, but I desperately do not want to.

That look is as desperate as it is blood-angry, and when I flip the album -- the giddy heights of "Badlands" having long subsided -- and hear "Adam Raised a Cain" with that long, low moan in the middle eight, I finally begin to know what rage might feel like, what an angry desperation to elevate above your circumstance might feel like. I think of my father, who I haven't seen in a good few months at least. I think of my stepfather and how futile it must feel to be fighting the raw memory of some shadow-dad. I hear it and think, on some precognitive level, holy fuck. This is what it must feel like when you're a man.

From this moment on -- and throughout those last few dodgy pre-teen years, before hip-hop and then punk will give me an identity -- Bruce Springsteen becomes this rock 'n' roll John Wayne, and I delve into his world with the same fervor as boys reserve for comic books. Fate will have it that a similar mythic world of rain-slicked streets, cars and girls named Candy will get blown to wide-screen around this time in movies like "The Outsiders" and "Eddie and the Cruisers."

One day, my mother's youngest sister Lisa is babysitting me along with her boyfriend Tommy. They're sitting on the couch across from me as I sit with my headphones on, running my finger down the lyric sheet of "Born to Run" in time with the music. Between songs, while I still have the headphones on and they think I can't hear, the following exchange:

"See that?"

"What?"

"He's reading the lyric sheet in time with the music. What a little weirdo."

Sept. 30, 1987

In the 1980s, after the "Born in the U.S.A." juggernaut has run over the entire United States, it is as easy as it will ever be to misinterpret Bruce Springsteen. Although this is probably not what is on my mind when I see Bruce Springsteen in the flesh for the first time. What probably is on my mind is something pretty harsh, for I am now 13 years old, have discovered the willy-nilly world of punk, post-punk and the accompanying disdain for all that has gone before. Karen Akers and I are in the stands at JFK Stadium on a late-September night, tiptoeing on the bleachers so that we can see U2, nearly 100 yards away as the crow flies. Karen is goth before goth is goth -- Siouxsie hair, blue-black lipstick and nails, and so on -- and this is also that strange moment when U2 are playing stadiums and can still be considered alternative.

In the fall night, we are exhilarated -- not only by the band, which is already playing stadiums and will soon be even bigger than that, but also by the fact that we were almost crushed at the gates of the show, on the way in, like English soccer fans. We're happy to be alive, but when Springsteen comes onstage to perform the Ben E. King classic "Stand By Me" with U2, it is like someone has farted in our sleeping bag. For this is the era when as much as he doth protest, the Boss was in his darkest hours of synthesizers (and not even the cool kind that OMD used) and jingoism, mislaid or not. It is all I can do not to boo him, because I am a teenager now, and that vulnerability and sincerity that Bruce so naturally tapped into feels like a kind of death. Everything is affected cynicism now, and I believe that Bruce has no place here, onstage with my avowedly political and anti-establishment Irish band. And playing that corny song to boot! Send him away, the creepy Little Lord Fauntleroy inside me intones.

But it's not as easy as all that, and some part of me knows this, even while navigating the black and cold waters of early high school. Because they did not want to see me get beaten up every day at the local high school, my parents have scrimped and saved to send me to a prep school, where the culture shock is such that at school events, my mother (now just 31) is often mistaken for my sister. As a result, I often find myself at a socioeconomic crossroads: All around me, there are rich white boys (rich by my count, at any rate) flopping around like fish on land, searching desperately for some kind of identity to cling to -- no different from me, really, when you take away the money and the easy comfort of suburban living and so on.

What matters at this crossroads -- 14, 15, 16 -- is the same thing that will matter for college and, sadly, even beyond that for some of us. It is a quest for authenticity -- that years-long process of grafting what you say you are (punk rocker, hippie, snarky activist) onto what you actually are. The process is arduous and I'd be lying if I said that the entire time, I am hanging by a thread, as I am caught between two worlds: one that is defiantly, stupidly poor, uneducated and paralyzed with derisive fear of all that lies outside of it, and another that is made bored and too comfortable by wealth and education, and still paralyzed with derisive fear of all that lies outside of it.

It is easy over these next bunch of years -- right on up to my 20s -- to feel as if I hate everything, to feel that all there is are these two worlds, nothing between, nothing after. But there is hidden solace, and it comes from Bruce. Though I'm not listening to him, his words are haunting me -- on the bus home from school, after an argument with my folks, late at night when I am alone on the kind of insomniac jag that only a diet of Dr. Pepper and Tastykake chocolate cupcakes can produce. All these kids, the voice says, man, just look at them. They're all on a race for some kind of authenticity, because deep down, they know that money has not and will not ever buy them the soul you have by accident, simply because you were born into shitty circumstances but with real people around you, who told you the truth and did not hide things in that uptight, white suburban way. Your curse is your cure, but you're still a misfit: You wanna find one place that ain't looking through you, you wanna find one place, you wanna spit it in the face of these badlands.

This is the type of thing I think at 13, 14, hell, 19, 20, 27, as I fall asleep at night, pathetic and self-congratulatory and narcissistic as all hell, all at once. And it contains things that are not so much nuggets of truth as they are almost prayers. And when they bring me comfort in this dark hour, when I am cutting my hair like Morrissey but still thinking on some level like Bruce Springsteen, I am thankful, and laughing at myself and guilty, especially on this night when I get home from the U2 show, so far from the couch and the headphones and the lyric sheet and the basement.

March 1, 1994

Joey Sweeney is standing in the living room of his first apartment, a hovel in South Philadelphia that is, at this moment, completely dark save for the blue light of the television and the snow reflected in the night outside. He is on mushrooms. Between the TV and the snow outside -- from a blizzard that only subsided in the last 18 hours -- there is an otherworldly glow and when he remembers this, even to this day, he still cannot remember if he is alone in the room or not. On the stereo is a record he rescued just days before from the dollar bin at the Book Trader -- "Nebraska." And if the cover image of bleak, high, lonely plains beyond a windshield suggests his soul, when he places it on the turntable and turns it up, it sounds like that even more so.

Joey Sweeney has been doing a lot of drugs lately, because it is the early '90s still (and the late teens, still), and, well, it just seems like that's what people are doing. He listens to "Nebraska" all the way through. That dull fire-alarm whine of the harmonica resonates with him to a degree that it feels like all he has ever known. When it is over, he just sits in the room, listening to the hail on the snow and the red light changing outside the window and he feels as bleak and as exalted as he ever has.

And then, his most lucid thought ever on the music of Bruce Springsteen: There is so much power in this music, he thinks, that even when it's making me feel bad, it's making me feel good. And that power is both beyond me and within me. The thought happens to be something that can be summoned, and also, for that matter, summed up, in one immortal Bruce line: It ain't no sin to be glad you're alive.

Just saying the line has mantra-like power; it's no accident that a Boss bio came out a few years later with that very title. That sentiment is out there in the cosmos, and as sure as it lands on someone else a few years later, tonight, in South Philadelphia, it lands on Joey Sweeney, cracks his 'shroomy daze and propels him to, at long last, stand up and turn on the lights!

Over the last few months, in one various stoner diversion or another, Joey Sweeney has purchased the entire pre-"Tunnel of Love" Springsteen catalog out of various dollar bins and yard sales at a grand total of no more than $8. As he arises, he recalls this, and thus begins a ritual -- which is really the right word for it, as the intent is to produce the same elation and abandon and love for life as you would get from, say, a gospel mass -- which he refers to in his heart of hearts simply, with no cheek or irony, as the Megamix. This is how it goes:

"Rosalita." "Darkness on the Edge of Town." "The Promised Land." "I'm On Fire." "Glory Days." "Badlands." "Adam Raised a Cain." "Hungry Heart." "Born to Run." "Thunder Road." And always, always, "Tenth Avenue Freezeout."

From this moment on, the Megamix becomes an intermittent fixture in Sweeney's life, a litany of FM hits that harness every transmuting power that rock 'n' roll has ever had to offer. The order may change, but the result is always the same: At the end, the living room floor is a gallery of Springsteen album sleeves, the long headphone cord is twisted up every which way -- Sweeney alternates between blasting the stereo and listening on headphones, sometime within one mix, because some rock needs closer attention -- and at least five of a six-pack emptied, ghosted, gone. It's like praying, Sweeney thinks sometimes, except better.

Sept. 21, 2001

It is but days after the nation has been shattered, and on every network, even the ones that don't matter, Bruce Springsteen is the first performer to appear on something that is called, with hushed tones of reverence, "America: A Tribute to Heroes," even though a lot of us still aren't sure whether this is political doublespeak because, hey, up until a few days ago, everything was. As a hardened music critic, guys like Sweeney bear a certain duty to be ready to chop their heroes at the knees in moments like this, when the portent is gooped like greasepaint. But as the screen goes from black up to churchy orange and Springsteen, surrounded by candles, black ladies and his wife, lurches into the first few bars of "My City of Ruins," Sweeney finds that he is a puddle.

This goes against everything writing about rock 'n' roll has taught him. This goes against everything one could reasonably assume in the rock world about a man like Bruce Springsteen and his relevance in the years 2001 and 2002. After all, the future of rock 'n' roll was made to be torn down by riot grrrls 10 years after the fact, in the sense that whatever used to matter is always torn down by trends whose most explosive, creative moments have already passed. Which is to say that the women-with-guitar bands of Ladyfest should be way more important than this white guy from New Jersey singing fake gospel -- with his wife, of all people.

But none of this matters because fuck you: Bruce Springsteen is healing a nation. Not the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. Not Moby. Not even, since we are traveling in descending altitudes of coolness, the fucking Goo Goo Dolls. Bruce Springsteen is on the television -- every television -- and he is healing us. Because we have been hurt. And because Bruce Springsteen not only cares about America, he is America, and what's even better, he understands just how fucked up it is and has always been to be an American, the ridiculous mix of the grand and pathetic, the painfully self-aware and the mockworthy clueless spiritual state that has gotten us so far ahead and so sadly behind the rest of the world. Some sick mojo the man has is melting us on our couches, making us into puddles of microwave-popcorn butter and that nasty aloe shit they put on Kleenexes now. We are a tired, huddled mass, punch-drunk and lucky as fuck that it wasn't us. And as Bruce is so humbled to remind us, well, it wasn't us this time, at least. And hey, remember the mantra: It ain't no sin to be glad you're alive.

Shares