When the Senate opened hearings this week about whether or not the United States should invade Iraq, it was billed as a way to begin focusing the American public on perhaps the nation's most pressing foreign policy question. But by the end of the second and final day of testimony Thursday, the hearings felt more like a cable news talk show than a meaningful national debate.

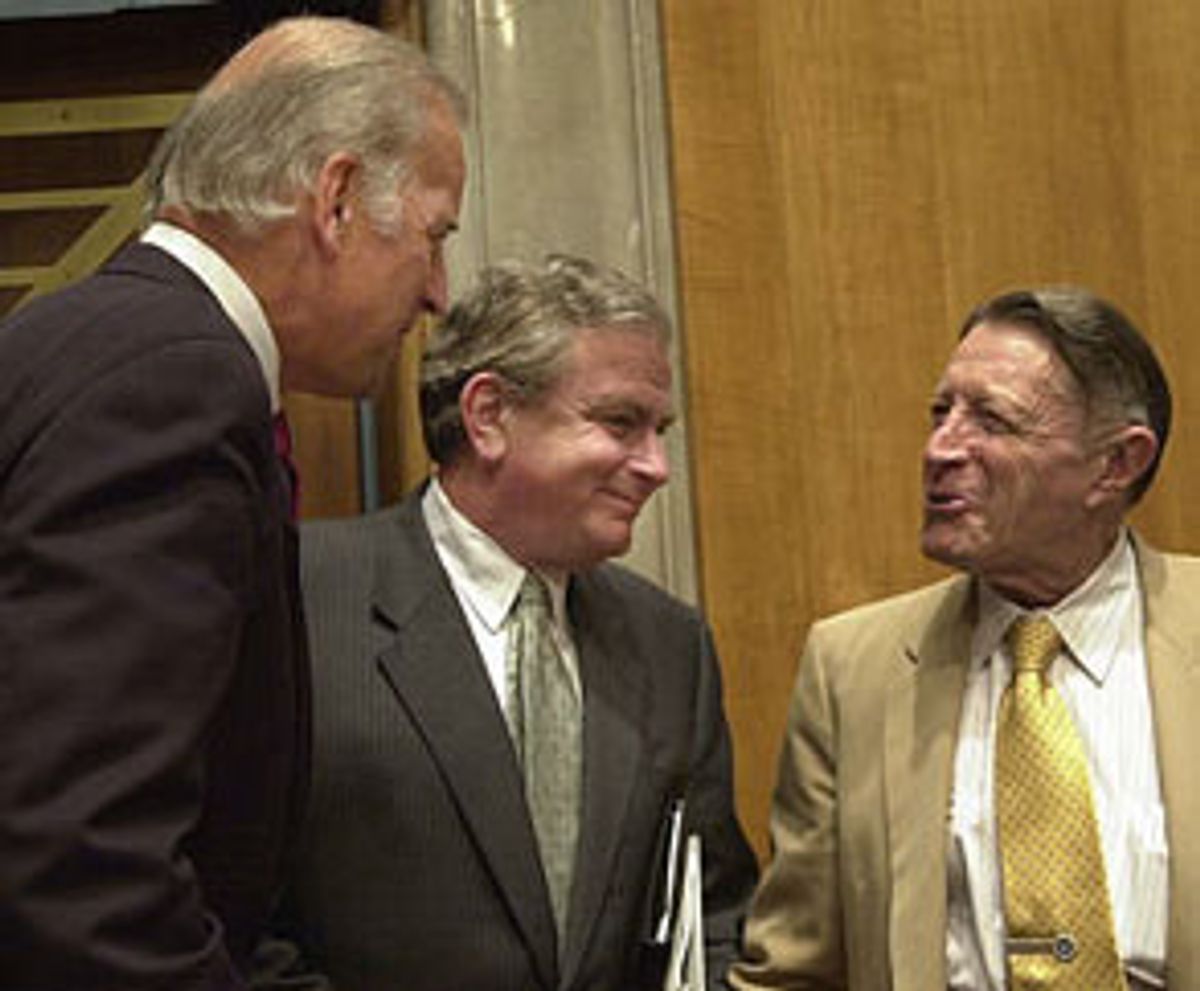

And since the committee's chairman, Sen. Joe Biden, D-Del., and ranking Republican, Sen. Richard Lugar, R-Ind., agreed not to ask members of the Bush administration to testify at these hearings, the session had the distinct feel of a talk show whose producer had failed to deliver the get.

Instead, visitors and viewers were treated to the simultaneous testimony of two former government officials, Casper Weinberger, who served as Ronald Reagan's secretary of defense, and Sandy Berger, Bill Clinton's national security advisor. In the clichéd formula of cable gabfests, the two were perfectly cast. Not only did they personify the partisan differences between Democrat and Republican, but also the difference between a diplomat and the Pentagon.

But since Berger and Weinberger are both long out of office, their testimony was of dubious value to the debate about reported plans to invade Iraq -- possibly early next year -- in an effort to oust Saddam Hussein. If you were to play a drinking game requiring a sip of beer every time one of the two men began a statement with an admission that they were speculating, everyone in the room would have been hammered at the end of the long afternoon. And that may have been an improvement.

For example, when Sen. Bill Nelson, D-Fla., asked the two whether al-Qaida terrorists were active inside Iraq, Berger said he knew of no significant al-Qaida activity in the country when he had access to classified information, but conceded that may well have changed since Sept. 11.

"I know that the intelligence community has been looking rigorously at the issue of whether there is a connection over the last 10 months," he said. "And obviously, it would be important to hear from them as to what they've established."

Weinberger said he believed there was a sizable al-Qaida presence in Northern Iraq -- an area controlled by Kurds who oppose Saddam and are protected from his attacks by a no-fly zone enforced by the U.S. and its allies -- but he conceded that he wasn't privy to firsthand information, either. "They have been welcomed to the country officially," Weinberger said. "Some of them are being paid as martyrs by Saddam Hussein." Weinberger said he received this information from "senior intelligence officials who did not wish to be otherwise identified," sourcing that wouldn't even satisfy a competent city desk editor at a small newspaper, let alone offer the American people a compelling reason to go to war.

But as in a cable talk show, the disagreement between the two witnesses did prove to be mildly entertaining, at least for political junkies. The most intriguing sound bite of the day came from Weinberger, who -- despite estimates that a war in Iraq may take up to a quarter of a million American troops -- compared possible military action there to the 1983 American invasion of Grenada. Though the committee heard earlier predictions that American troops would have to stay in Iraq for months or even years after Saddam's departure, Weinberger pointed to the Grenada invasion to suggest the United States could get out of Iraq quickly.

"We went into Grenada with more troops than everybody thought we needed, and we had a very successful operation and prevented the kidnapping and detention of American students, and we got out," he said. "And we got out in something under a month. And a couple of months after that, there was a free election and we have not been back."

Berger offered a Caribbean military reference of his own for a possible U.S. invasion of Iraq, warning that toppling Saddam would be much more difficult than the campaign in Afghanistan. "The Iraqi armed forces are significantly stronger than the Taliban and Saddam Hussein's grip is tighter," he said. "We should be very wary of turning the U.S. military into an emergency rescue squad if Saddam Hussein moves his tanks against insurgents we are backing. America does not need a Bay of Pigs in the Persian Gulf."

The two also disagreed about whether or not President Bush should consult with Congress before launching a military strike against Iraq. Weinberger said it is "always desirable to have congressional support," but said the president has "very substantial freedom to do the things that he considers necessary in foreign policy." Berger, by contrast, said: "Congress becomes, as always, the vehicle for expressing American public support. And we've learned in the past that without sustained American public support, we can get ourselves in trouble."

The most heated exchange between the two came over the timeline of a possible U.S. strike. Weinberger called for swift action against Saddam, while Berger endorsed a more measured approach. The former national security advisor said Bush should go back to the United Nations to call upon Saddam to allow weapons inspectors back into Iraq "to serve our purpose of gaining some greater support in the world for an action we may have to take."

Weinberger dismissed the diplomatic route, saying Saddam "had four years in which he has succeeded in throwing out an absolute U.N. resolution. And asking for it again is asking for more useless promises from him."

For all of the lively back-and-forth, one thing became clear at the end of this second day of hearings. There will be no meaningful congressional hearings about Iraq until some current employees of the executive branch make their way to Capitol Hill. That's not expected to happen until fall, at the earliest.

Shares