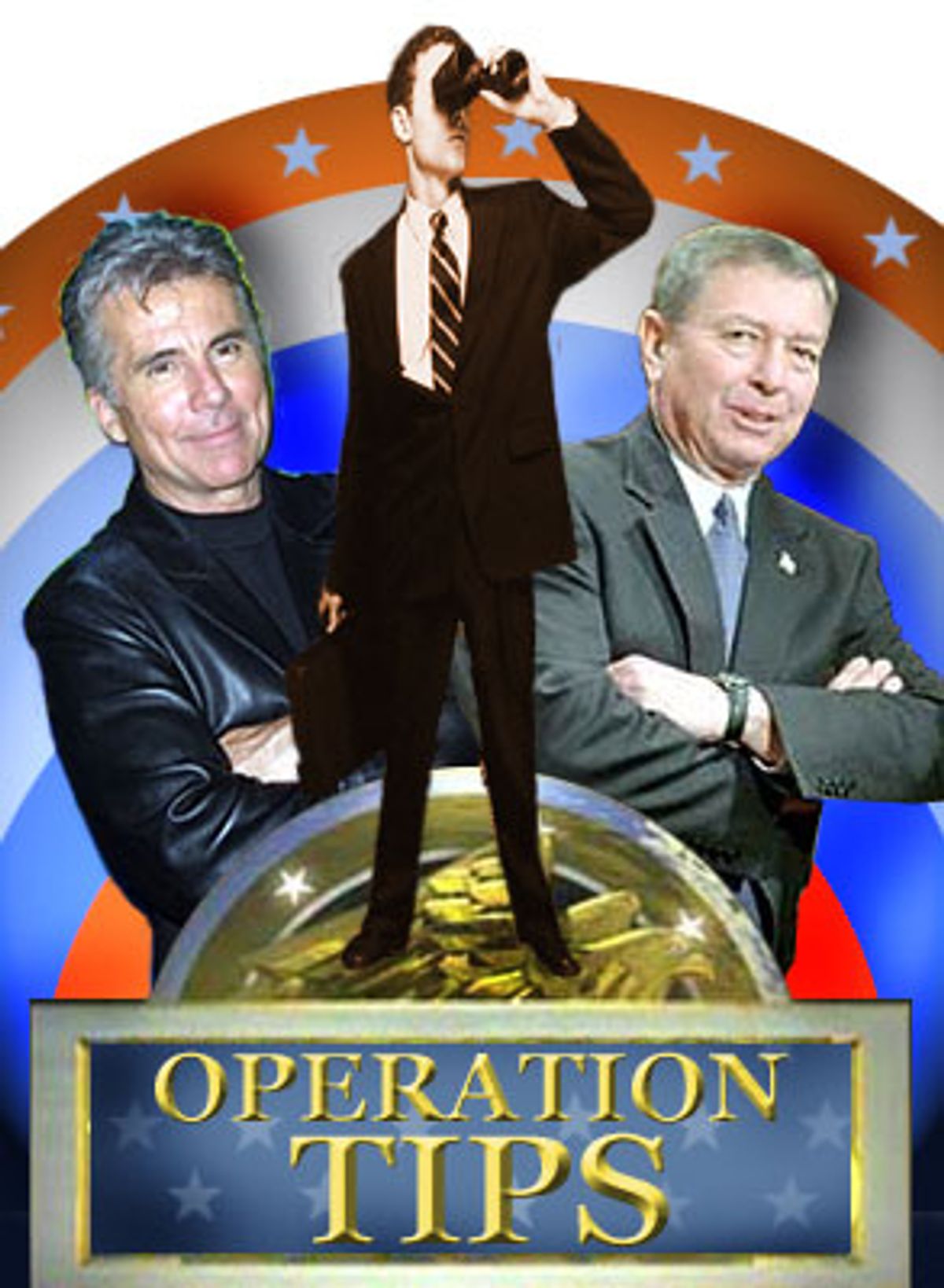

When Attorney General John Ashcroft announced the formation of Operation TIPS, a planned army of tens of millions of American volunteers charged with ferreting out terrorists in their neighborhoods, plenty of pundits questioned whether Americans spying on Americans was a good thing. Very few people asked exactly how it would work, and the Justice Department didn't offer any clues.

To find out, I went to the Citizen Corps Web site, then to the Terrorism Information and Prevention System (TIPS) page, and signed up as a volunteer. I quickly discovered that TIPS is having a devilish time getting off the ground. After an initial welcome from the Justice Department, I heard nothing for a month. When I finally called two weeks ago to ask what citizens were supposed to do if they had a terror tip, I was given a phone number I was told had been set up by the FBI.

But instead of getting a hardened G-person when I called, a mellifluous receptionist's voice answered, "America's Most Wanted." A little flummoxed, I said I was expecting to reach the FBI. "Aren't you familiar with the TV program 'America's Most Wanted'?" she asked patiently. "We've been asked to take the FBI's TIPS calls for them."

Has Ashcroft turned his embattled volunteer citizen spy program -- which has been blasted by left and right alike -- over to Fox Broadcasting's "America's Most Wanted"? If so, the connection shouldn't be all that surprising. Ashcroft's Justice Department and John Walsh's popular crime-busters show have been a mutual-admiration society for some time now. Walsh started coaxing ratings out of the 9/11 disaster for Fox TV while the dust was still settling from the twin towers' collapse. Only two days after the attack, Walsh loaded his whole production team onto a bus in Indiana and drove the show to ground zero, where, he claimed, government officials had told him to "help us catch these bastards."

But it's still hard to nail down the exact nature of the relationship between TIPS and "America's Most Wanted." Officials at the Justice Department and Fox Television denied reports of a formal link -- even though their switchboard operators last week were working happily in concert. "TIPS doesn't exist yet," said Linda Monsour, a spokeswoman for the attorney general's Office of Justice Programs, which will oversee Operation TIPS if it gets going this fall as planned. Then Monsour conceded that the Justice Department, which has an $8 million start-up budget for TIPS, had already begun signing up individual volunteers, in advance of the program's ratification by Congress. She wasn't exactly sure how those calls were being handled. But she denied knowing anything about a hotline to the Fox show. "It's probably something I should explore," she said.

"America's Most Wanted" publicist Kim Newport also denied knowing about a formal link between the Justice Department and the TIPS program when interviewed last Friday, but she did acknowledge that the show regularly takes tips from callers about possible terror threats. "We have been taking calls on terrorism," she said. Noting that TIPS is not officially running yet, she mused, "Maybe the Justice Department just turned to us because that's how our program works." Newport says the show turns over all of its terrorism tip calls to the FBI, or to the Postal Inspector's Office if they relate to anthrax threats.

Clearly, someone in the Justice Department decided to enlist the show in processing TIPS calls, and civil libertarians aren't sure whether the Fox-TIPS synergy is funny or scary or both. "On a certain level, it's laughable -- a Keystone Kops kind of thing," says Bill Goodman, legal director at the Center for Constitutional Rights. "But the frightening thing about it is, what if someone actually did find evidence of a real terrorist ring, and they brought it to a TV station instead of the FBI?"

"This is really, really bad judgment on the part of the administration," says Rachel King, lobbyist for the American Civil Liberties Union, who was "stunned" when I told her TIPS calls were being directed to the Fox show.

"TIPS was supposed to be about reporting suspicious behavior, which would then be interpreted by the FBI or local law enforcement. Now it turns out the information is being handed to a TV program that encourages vigilantism. What will 'America's Most Wanted' do with the information? It's kind of mind-blowing. It was bad enough when the reports were going to be filed with the Justice Department or the FBI. With this information in private hands, who's going to protect people from malicious complaints?"

A spokeswoman for Sen. Joe Lieberman, D-Conn., whose Governmental Affairs Committee is handling the Senate's version of the Homeland Security bill that would include TIPS, said, "It's inappropriate for a TV program to be taking these kinds of calls. That is certainly not what Sen. Lieberman has in mind."

Observers on all sides of the debate are still trying to figure out what Ashcroft has in mind.

The goal of TIPS, for those who missed the initial surge of coverage, was to enlist patriotic Americans in the hunt for the terrorists in our midst -- much the way, it should be said, "America's Most Wanted" enlists ordinary TV viewers in catching bad guys. Ashcroft's vision was that millions of TIPSters would volunteer to look for the odd, the unusual, the suspicious among us, and would report them to the Justice Department, which would then evaluate our evidence and decide what to do with it.

When first announced as part of President George W. Bush's Citizens Corps volunteerism initiative during his State of the Union address, TIPS was billed as "a national system for reporting suspicious and potentially terrorist-related activity," which would "involve the millions of American workers who, in the daily course of their work, are in a unique position to see potentially unusual or suspicious activity in public places." The plan initially called for a million volunteers in 10 urban trial centers, which were to begin operations this month.

But when Congress and the public began to imagine phone repairmen, maids, postal workers and cable guys nosing around people's houses and reporting on whatever struck them as suspicious, an uproar ensued. Critics noted the parallels between TIPS and life behind the Iron Curtain, where neighbors spied on neighbors, and Ashcroft seemed to retreat, canceling the 10-city trial (but not the online call for individual volunteers). He delayed the official kickoff of the program until autumn and said that, instead of millions of citizen volunteers, he would aim the program at truckers, postal workers and others in particular industries who would be well-positioned to notice unusual activities. The Postal Service immediately said it would not cooperate.

TIPS ran into political fire especially on the right. House Majority Leader Dick Armey, R-Texas, has attached a measure to the House version of the Homeland Security Bill barring any government program from having citizens spy on other citizens. The bill has 295 sponsors, according to Armey spokesman Richard Diamond, who predicts, "TIPS is going to die." He says that although the Senate version of the bill does not address the program, Armey, one of the most powerful members of the Republican-dominated House, has determined that his measure "will stay in the bill in conference" when the two chambers' versions of the bill are reconciled.

But he may not get his way: Lieberman considers Armey's opposition to TIPS to be "too broad," according to one source. The Connecticut Democrat is said to think that modeling a program on the Neighborhood Watch idea and enlisting the help of workers in certain industries "makes sense." Civil rights groups are said to be livid at Lieberman's reported waffling on TIPS.

But whatever Lieberman decides, congressional opposition to TIPS is strong. So is Ashcroft rethinking his plan to establish a sprawling team of feds to oversee the operation? Is he planning on turning it into a television program, where people will rat on their neighbors, and John Walsh and his "America's Most Wanted" TV crew will come banging on the doors of the suspected terrorists, demanding that they come clean? It could be novel way of getting around congressional reservations and restrictions. Armey's measure, for example, would bar only "the government" from running any program having citizens spying on citizens -- but it might not apply to a Fox-run effort.

Certainly it wouldn't be the first time Walsh and the feds have cooperated. On the 30-day anniversary of the Sept. 11 attack, Fox, at the administration's request, preempted its Friday evening schedule to air a special Walsh production called "America's Most Wanted: Terrorists -- A Special Edition." Fox Entertainment Group president Sandy Grushow told Daily Variety, an industry newspaper, "This is something we wish we had more time to put together, but it seemed quite important to the FBI and White House that we do this as soon as possible." Walsh claimed later that the program netted 1,500 call-in tips, compared with the program's usual 200 to 300 phone tips following a show. Clearly the administration needed the help: Even today, the FBI doesn't have a dedicated line to handle terrorism tips. People are expected to contact their local FBI office. The New York office reports that it was overwhelmed last fall with more than 100,000 calls per month. Now it no longer bothers to separate terror tips from regular crime tips.

It's still next to impossible to get firm answers about any aspect of TIPS. After my conversation with Justice Department spokeswoman Monsour last Friday, operators at the attorney general's office have apparently begun sending callers to a number that really is the FBI, not the "America's Most Wanted" switchboard. "We are now being told to refer TIPS calls to the FBI," an operator told me. But when I phoned the number (which proved to be the FBI's main Washington switchboard), I got little help. After an interminable period of Muzak, an operator said she couldn't help me. "You should probably call your local FBI office to report any suspicious activity," she said. An FBI spokeswoman then told me that the bureau is not fielding any calls from TIPS volunteers. "That's being handled by the Justice Department," she said. I'd finally come full circle with my questions about where TIPS calls should go. Additional calls to Monsour's office to clarify the relationship went unreturned.

I tried the "America's Most Wanted" hotline one last time. And once again I was told that the show was "helping with the TIPS calls" and that any information about suspicious terrorist activity would be "forwarded to the FBI."

Even if the TIPS-Fox connection is just a stopgap measure while the Justice Department tries to figure out what to do with a program nobody but the president and the attorney general seems to support, the solution shows Ashcroft's tin ear when it comes to privacy rights. The idea of privatizing a citizen spy operation is alarming to many civil libertarians, not reassuring.

"This is all very, very disturbing," says the ACLU's King.

Shares