Some day in the future, historians may look back on Aug. 7, 2002, and see it as a snapshot of Vice President Dick Cheney at a crossroads: On a brilliant morning in San Francisco, hundreds of protesters greeted him outside the elegant Fairmont Hotel, denouncing him as a corporate criminal and a warmonger. Inside the Fairmont, a crowd of reporters was waiting for him to answer their questions. Down the road in Fresno, Republican loyalists were waiting to hear him at a luncheon speech.

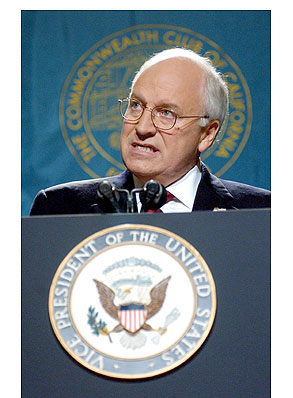

The fundraiser was a success. The vice president avoided the protesters — most of them, anyway. And in his appearance before 500 members of the august Commonwealth Club and perhaps 50 journalists, he delivered a speech and handled nine questions. Over the course of almost an hour, Cheney displayed the understated grace and self-effacement of a political pro, managing to say almost nothing new and deflecting most of the questions.

By current standards, that’s got to count as a pretty good day for Dick Cheney.

He has been pursued relentlessly by bad news throughout this hot, difficult summer. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating questionable accounting practices at Halliburton, where he was chief executive officer before signing on to the presidential campaign of George W. Bush. Because the company waited a year to notify shareholders of a key bookkeeping change, critics say, its stock prices were inflated. Cheney sold his Halliburton stock — and made $40 million, by some press accounts — shortly before its value began to tank. And during the 2000 campaign, recent reports say, the Bush-Cheney team used jets provided by Halliburton and now-bankrupt energy-titan Enron, which is, of course, also under federal scrutiny — though the White House now insists the campaign paid for those flights.

While the Bush administration has given Cheney glowing votes of confidence, pundits have begun to wonder whether Cheney is vulnerable — because of his heart disease, or because of the scandals — and whether the president will seek a stronger partner when he seeks reelection in 2004.

“This is a guy whose résumé is the résumé of the wealthy Republican businessman,” Paul Light, an expert on the vice presidency at the Brookings Institution, told the Christian Science Monitor last month. “Dick Cheney is the Republican as fat cat. And the more the public focuses on the economy, the more Cheney becomes a liability for … the president.”

In response to the storm, Cheney has run for cover. The San Francisco Chronicle jabbed him Sunday for going 77 days without taking a question from the press. By Wednesday, the count had risen to 80 days. Such silence assured that his visit to San Francisco would have a high news profile. And though it was billed as a speech about “economic and national security issues,” the appearance was really a chance for Cheney to answer questions — about Halliburton and other corporate scandals, his position as a corporate role model, and about the stock market, the economy, the Middle East and the talk of looming war against Iraq — in a controlled setting.

From Cheney’s perspective, perhaps, it worked. We learned that Cheney has “great affection and respect” for his former colleagues at Halliburton, but nothing more about the company and the SEC investigation. We learned that the Clinton administration and Sept. 11 are to blame for the economy, but not the role of Bush tax cuts in causing the first federal deficit in years. We learned that he’ll consult his wife and doctor about whether to run for a second term as vice president, but not whether he sees himself as a political liability for a White House dogged by its association with the corporate-corruption scandal.

It’s not that reporters didn’t try to ask tough questions. There just wasn’t a chance. The Commonwealth Club invited its members to submit questions in writing, with the promise that they would be selected by club officials and then addressed by Cheney after the speech. Reporters’ questions were graciously thrown into the mix. An hour before Cheney arrived at the Fairmont, we were buzzing over our lines of possible inquiry. Who knew what he might say? Who knew when there would be another chance to ask?

“We have to flood him with questions,” one reporter said to a colleague.

“What questions do we flood him with?”

“Halliburton,” she said. “We have to ask about Halliburton.”

“You know he won’t answer questions about Halliburton.”

Some planned to ask about Enron’s relationship to the California energy crisis. Some would ask about the apparent collapse of Republican Bill Simon’s campaign for governor of the state; Simon is mired in a corporate scandal of his own.

“Given that taxpayers are paying your salary, why shouldn’t they know which lobbyists met with your energy task force?” one rehearsed aloud. “That’s my question — it’s simple.”

We took the exercise seriously. Privately, cunningly, with careful attention to each word and each subtle shade of meaning, I crafted questions that would leave Cheney no room for evasion.

Mr. Vice President, according to a recent New York Times poll, 66 percent of the public believes big business has too much influence on the Bush administration. Another 62 percent say the recent accounting scandals pose “a very serious problem” for the economy. Given questions about your record as the chief at Halliburton, are you undermining the credibility of the White House?

There is much discussion and disagreement in the Bush administration over a possible invasion of Iraq. When, in your opinion, would such an invasion be justified? Some top Republicans recently have suggested an invasion is inevitable. Do you agree? Why or why not?

Why have you not done an interview or a news conference with the press in nearly three months?

Do you expect to be on the GOP ticket as the vice presidential candidate in 2004? Under what conditions would you reconsider plans to seek reelection?

In the end, one of my questions actually got asked. He didn’t evade it, but he didn’t exactly answer it, either.

Cheney used his speech to extol the Bush administration’s handling of the economy. He acknowledged a “serious economic slowdown,” but blamed it on the “massive disruption” caused by the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and on two terms of President Clinton. “The Bush tax cut came just in time,” he said. In the fourth quarter of 2001, “tax relief helped us climb out of the recession.”

He made no mention of the $165 million deficit expected this year, a deficit that critics blame on the tax cuts, nor of the “double-dip” recession that some economists are now predicting.

And while he said he was not prepared to analyze the recent stock market spiral, he noted that the slide began during the waning days of the Clinton presidency. “Some of the more recent declines are at least partly explained by a loss of confidence in the corporate sector,” Cheney acknowledged. But he insisted that Bush has “acted firmly” to win reforms. “The system rests on confidence,” he said, “the basic belief that corporate officials are truthful, numbers are real, audits are real and independent.”

It was at about that time that a handful of protesters stood up in the audience and began chanting: “Cheney is a corporate crook! No war in Iraq!” As they were led away by Secret Service agents, Cheney said: “Thank you!” The audience responded with nervous laughter, then applause. “Acts of fraud and theft are outside the norm in corporate America,” he resumed, “but when those acts do occur … wrongdoers must be held to account.”

Cheney segued into the administration’s all-purpose agenda, calling for “reliable and affordable supply” of energy, support for small businesses, reduced federal regulation, and free trade. He expressed pride in the U.S. armed forces, and warned that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was continuing efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction.

When the question-and-answer session began, it was clear that the club members and reporters were seeking detailed answers. Commonwealth Club CEO Gloria Duffy tossed him some fastballs and a couple of softballs, and even allowed a couple of members to ask their questions directly from the floor. But Cheney’s answers were rarely definitive, and without a chance for follow-up, he got to spin them his way. If Iraq were to allow a return of U.N. arms inspectors, one questioner asked, would the administration hold off on plans for war? Cheney talked tough but made no commitment.

“The president has not made a decision at this point to go to war,” he said. “Many of us I think are skeptical that returning inspectors will solve the problems,” he added, suggesting that Saddam’s renewed interest in the issue was just “an effort to obfuscate and delay and avoid having to live up to the accords he signed” after the Gulf War.

When asked to discuss possible links between the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Iraq and how they affect U.S. policy, he simply did not answer the question, but instead talked about the need for reform in the Palestinian Authority. Asked about the Halliburton accounting flap and its possible connection with the crisis in investor confidence, he expressed “great affection and respect” for his former colleagues but again did not answer, citing the SEC investigation and insinuating the media was to blame for his silence.

“I am of necessity restrained in terms of what I can say about that matter,” he explained, “because there are editorial writers all over America poised to put pen to paper and condemn me for exercising undue, improper influence if I say too much about it.”

The last question read by Commonwealth CEO Duffy: “Do you expect to be on the GOP ticket as the vice presidential candidate in 2004? Under what conditions would you reconsider plans to seek reelection?” That was my question, though others may have asked something similar. But Duffy added her own quip: “Put a different way, how’s your heart?” Certainly that wasn’t what I was getting at, but Cheney took up her approach to the question.

“In terms of what happens next, he [Bush] will have to make a decision by this time about two years from now, when the convention rolls around,” Cheney told us. “If the president is willing and my wife approves and the doctors say it’s OK, I’d be happy to serve a second term. But again, that’s his decision to make.”

It was hardly the statement of a man hungry for the job. In fact, Cheney complained that, being a public official, “certain penalties” make one a “target.” In the end, he made no commitments and he left his options open. He gave his opponents nothing to attack.

With that non-answer, Cheney’s skein of 80 days without answering a question from the press came to an official, if unsatisfying, end. His motorcade sped past the remaining protesters to his Fresno fundraiser, away from all their troubling questions, at least for now.