In the spring of 2001, shortly after the Bush administration had taken office, a delegation of Saudi diplomats attended a meeting at the Pentagon with Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul D. Wolfowitz. As the meeting was breaking up, one of the attendees, Harold Rhode -- a Pentagon employee and Wolfowitz protégé then serving as Wolfowitz's "Islamic affairs advisor" -- approached Adel Al-Jubeir, a soft-spoken Saudi diplomat who once served as an assistant to the Saudi ambassador and today is foreign policy advisor to Crown Prince Abdullah.

Rhode told Al-Jubeir that once the new administration got its affairs in order there'd be no more pussyfooting around as there was in the Clinton days, according to a source familiar with the meeting. The United States would take care of Saddam, start calling the shots in the region, and the Saudis would have to fall in line. Al-Jubeir demurred. These were issues the two allies would certainly discuss, Al-Jubeir told the American.

Rhode then shoved his finger in the diminutive Saudi's chest and told him, "You're not going to have any choice!"

Rhode's antics caused a brief frenzy on the phone lines connecting the Pentagon, the State Department and the Saudi Embassy. And the embarrassing incident may have cost Rhode a high-level appointment in the Pentagon's Near East and South Asian Affairs office. But the incident -- among others -- set the tone for the Bush administration's relations with the Saudis, which were deeply troubled well before Sept. 11, when more than a dozen Saudi nationals drove planes into the Pentagon and the World Trade Center. After the Washington Post reported earlier this week that a Pentagon advisory board listened to a speaker (and a peculiar one one at that) describe Saudi Arabia as America's enemy, suggesting military action against the desert kingdom, Pentagon officials were quick to insist that such views were by no means those of the Pentagon or the Bush administration.

But the touchiness of the response and the delicacy of the issue underscores a reality that the Saudis and high-level administration officials well understand: Many, perhaps most, of the Bush administration appointees at the Pentagon today are only slightly less hostile to the Saudis -- and many of America's other traditional Arab allies -- than the speaker at the briefing.

And it spotlights an unsettling problem among the men deciding whether we should wage war: The relationship between career military officers and their civilian bosses at the Pentagon are the worst they've been, some insiders say, in more than 20 years, even more divisive than they were during the Clinton years. There is no clear resolution to it, and particularly in the near future, the rift could have dangerous consequences.

The Bush administration's most right-leaning political appointees are concentrated at the Pentagon. And nowhere is that tilt more evident than in its Middle East policies. The Bush appointees have not just ignored recommendations from military advisors and civil servants but have often ousted or sidelined those who have had the temerity to offer any policy advice. Over the last 18 months, there has been an exodus of career civil servants leaving the Pentagon policy shop for stints on Capitol Hill or with other Defense Department-affiliated institutions, according to a half-dozen such departees who spoke to Salon -- far more than is normally the case when administrations change from one party to the other. Many of those slots have been filled by ideologues and think-tank denizens who can be relied on to serve up the right kind of advice to their superiors.

When most people think of neo-conservatives at the Pentagon, they think of men like Wolfowitz, the deputy secretary, and Richard Perle, the chairman of the Defense Policy Board -- the panel that heard the anti-Saudi briefing. But the second tier of civilian appointees at the Pentagon is stacked with Wolfowitz and Perle protégés who are in many ways even more conservative in their views than their mentors and -- as the Rhode incident shows -- a good deal more hotheaded. And even Wolfowitz strikes many in the military as more than a touch conservative. "Wolfowitz is a right-wing sucker," says retired Army colonel William Taylor, a defense policy analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. "He's a good guy, a smart guy. But he's to the right of Genghis Khan."

In the minds of these second-tier appointees, taking out Saddam Hussein is only part of a larger puzzle. Their grand vision of the Middle East goes something like this: Stage 1: Iraq becomes democratic. Stage 2: Reformers take over in Iran. That would leave the three powerhouses of the Middle East -- Turkey, Iraq and Iran -- democratic and pro-Western. Suddenly the Saudis wouldn't be just one more corrupt, authoritarian Arab regime slouching toward bin Ladenism. They'd be surrounded by democratic states that would undermine Saudi rule both militarily and ideologically.

As a plan to pursue in the real world, most of the career military and the civilian employees at the Pentagon -- indeed most establishment foreign policy experts -- see this vision as little short of insane. But to Bush's hawkish Pentagon appointees the real prize isn't Baghdad, it's Riyadh. And the Saudis know it.

In his new book, "Supreme Command," Johns Hopkins University professor Eliot Cohen argues that the best wartime civilian leaders are those who don't take the generals' word for it. They prod and question and they don't hesitate to overrule their chiefs when their advice doesn't square either with common sense or the larger political or geopolitical logic. Cohen's thesis got some confirmation in last fall's Afghan war; after Sept. 11, the Joint Chiefs wanted to delay an attack on Afghanistan to await favorable weather conditions and gain time to position extensive assets in the region.

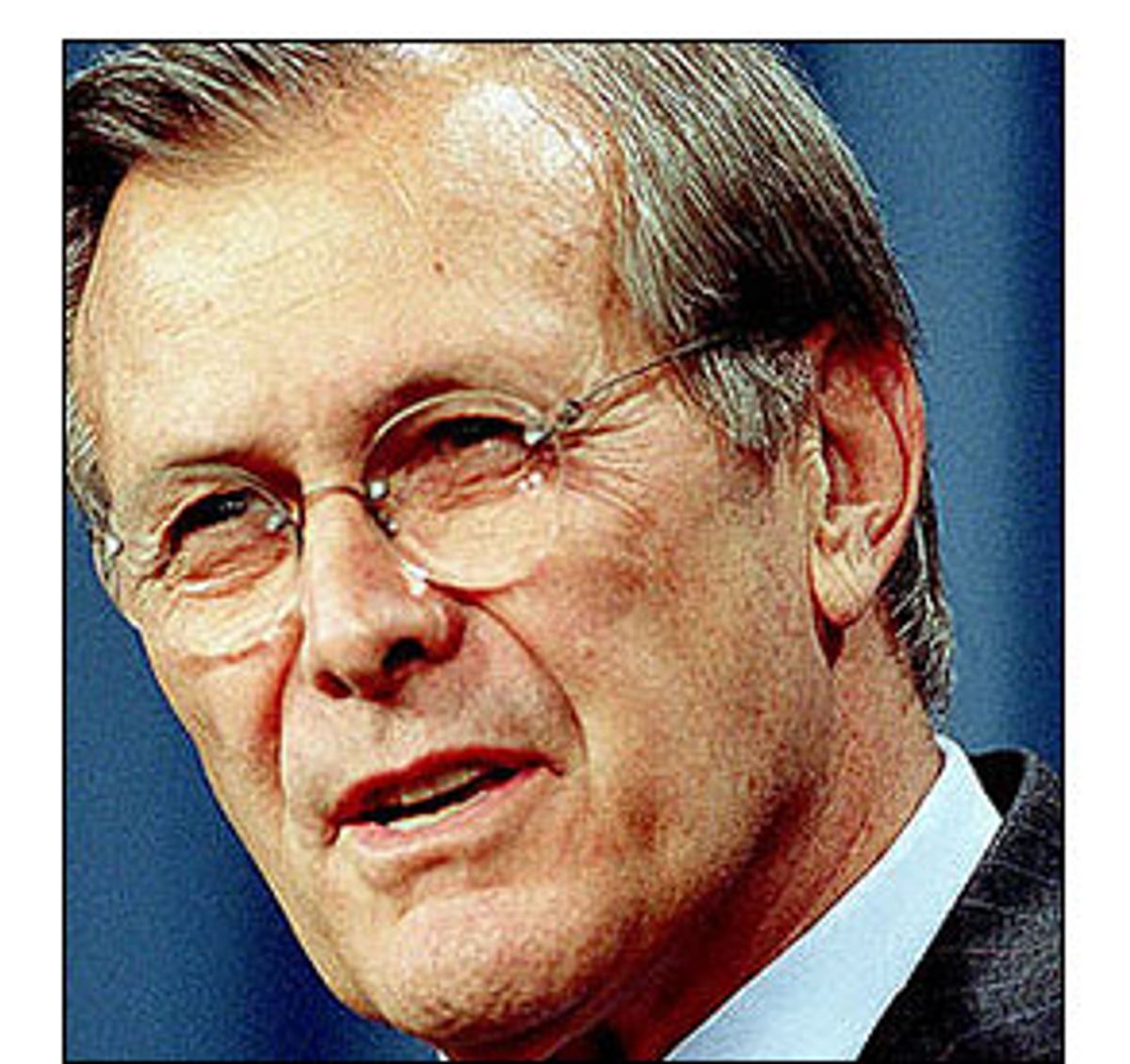

The U.S. Central Command, responsible for Central Asia and the Middle East "wanted very much to wait until the spring to start the operation," says one defense policy analyst in close touch with military and civilian Defense Department officials. "The civilians just said 'No. We want to start in October. We can't let 30 days pass since Sept. 11.'" And, in retrospect, few foreign policy experts would disagree that that was the right course. "I don't think there's any question," says one Clinton Pentagon official, "that Enduring Freedom was fought differently because [Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld] was in there prodding, saying, 'General, that's not creative enough. General, you're not giving me the options I want.' I have no doubt that Rumsfeld was personally responsible for the fact that Special Operations forces were introduced early into Afghanistan."

But Afghanistan was one case. And while nearly everyone agrees -- in theory at least -- that civilians should prod the chiefs for better answers and question their preferred options, there's a fine line between a willingness to overrule military advice and an unwillingness to listen to it at all. And on the peace process, Saudi Arabia and -- most pressingly -- Iraq, Bush Pentagon appointees are increasingly opting for the latter course.

One staff officer who worked under and briefed high-level officials in both administrations describes one administration easily cowed by generals' sober descriptions of the dangers of a military engagement in a country like Iraq and another administration virtually indifferent to them. When discussing a major move like an invasion of Iraq, says this retired officer, "you have to look [a civilian defense appointee] in the eye and say, 'Sir, do you understand that you cannot control the outcome of the enterprise on which we are about to engage?' If he moves his head up and down to that, then you can ask him the second question.

"In the Clinton administration, they'd look at you with that bovine stare. And then their head would start moving laterally," the retired officer said. "But these guys seem to have assumed away that problem. They seem to believe they can control the outcome. Every man in uniform knows that's not true."

Now, many on each side are viewing the other through a prism of caricatures and clichés. The uniformed officers and civil servants tend to espouse establishmentarian views of proper U.S. defense policy in the Middle East and the operational details of how to fight actual wars. They see the difficulties and problems in relations with countries like Saudi Arabia but are more interested in bettering relations with those regimes than ousting them from power. These career professionals see the civilian appointees as uninformed zealots who've spent most of their time in think-tanks and have no actual military experience. The civilians tend to see the generals they command as unimaginative bureaucrats who lack the will to actually fight.

This split is also heating up over what defense policymakers call "transformation" or the "revolution in military affairs" -- a host of budgetary, structural and weaponry decisions aimed at revolutionizing the American military to confront the challenges of the 21st century.

The big push for transformation comes from Rumsfeld (and not Wolfowitz and Co., who focus more on regional policy) and the tight circles of his advisors and aides. Most prominent among them is Stephen A. Cambone, Rumsfeld's chief deputy, who earlier served as the staff director of the Rumsfeld Commission on National Missile Defense. Cambone has earned the fierce enmity of almost every officer at the Pentagon for chewing out generals while remaining unassailable since he has his boss's complete confidence.

Many defense analysts doubt Rumsfeld has a coherent vision of transformation but most believe that his aggressive stance on the issue -- signaled most prominently by the high-profile axing of the Army's new, but costly and unwieldy, Crusader artillery system -- is a positive development. In the complex calculus of civilian military oversight, there are few issues that the military is less capable of addressing on its own than the sort of broad, sweeping changes implied by transformation. Making revolutionary changes to the armed forces necessarily means ditching weapons and ways of operating that the heads of the services have built their careers around.

"It's more than human nature can deliver," says defense expert Edward Luttwak, to expect Army generals who built careers around artillery to turn around and scrap a new artillery system like Crusader. Similarly, can one really expect the top Air Force generals -- most of whom were fighter pilots -- to back taking money out of fighter jet production so that it can be reallocated for more bombers and unmanned drones? Arrogance and bad manners from Rumsfeld and Cambone may have complicated matters, but transformation requires hard choices that simply cannot be sweet-talked away.

But the mix of the antagonism over regional defense policy -- particularly in the Middle East -- and the transformation debate has produced a level of antagonism between civilians and military at the Pentagon that is actually far greater than it was under Bill Clinton. And no one is more surprised than the military itself.

"By the time the Clinton era was ending, a lot of the military guys still held the view that we really don't like Clinton, and boy, if we got a Republican in here, it would be oh happy day and we could really ramp up the budget and go to town," says one former career officer who remains in close touch with members of Joint Staff. Only it didn't turn out that way. "They throw their lot in with the Republicans. The Republicans come to office. And wham! They're worse off than they were at the end of Clinton. Even though they're going to get more money in the budget, they're going to have little or no say-so over where it goes or how it's done. The relationship between them and the new overseers is testy at best. It's very strained."

The rude awakening the armed services got in February 2001 points up a too little appreciated fact about the Clinton Pentagon. As a group, the American military never lost its distrust and even enmity toward Bill Clinton. And they are far more positively inclined toward George W. Bush. But in terms of calling their own shots, the brass never had it so good as it did under the former president -- particularly after Clinton's first couple of years. Clinton-era defense officials were seldom in a position to go head to head with the generals on truly important matters, with some simply lacking confidence in their grasp of military affairs. Because of that they were often ready to defer to those in uniform.

Others at the Clinton Pentagon were seasoned defense professionals -- men like Defense Secretary William Perry and Undersecretary Walt Slocum -- who had as deep a grasp of military affairs as anyone who has ever served in their posts. But they still operated in the larger knowledge that their civilian superiors lacked the political clout to back them up in a major confrontation with the military. Out of necessity, defense officials reached a modus vivendi with the military, and the two sides ran the Pentagon by consensus.

Despite the lip service he paid to "transformation" on the campaign trail, what the military expected from George W. was Bush redux: more or less unquestioning support for the armed forces. But they soon learned that Rumsfeld and his new team had taken a very different lesson from the often fractious relationship between the military and the outgoing administration. While Rumsfeld and Co. were no less sour on Clinton defense policies, they also believed that the civilians needed to bring the military to heel. "They thought the uniformed military had run roughshod over the process at the Pentagon," explains one retired Marine with long service at the Pentagon. "They thought the civilians really needed to take over, and that attitude became very evident in the first couple of weeks."

Though major defense cuts began under the first Bush administration, the political tenor of Bush I was almost perfectly suited to the officer corps: culturally pro-military and ideologically middle-of-the-road conservative. The ideologues who populated the Reagan Pentagon were occasionally irksome to the Joint Staff. But they were united by a common goal: their opposition to the Soviet Union. And given the historical moment -- the arms buildup that hiked funding for numerous weapons programs while seldom cutting any -- latent ideological tensions seldom came to the fore.

By contrast, Bush II, though also willing to spend, is far more ideologically conservative and doesn't share the reluctance that earlier Republican administrations had at scrapping weapons programs. Most important, these appointees have the political clout and the willingness to fight with the military to get their way, and have been, in their own way, beneficiaries of the historical moment -- the successful prosecution of the U.S. war in Afghanistan. The new team turns out to be as likely to dismiss professional military advice as the old team was to accept it. And that accounts for the case of whiplash that the Pentagon brass has suffered for the last 18 months.

What makes civilian control so important is that military officers have a tendency to become consummate ideologues, too -- not of a political ideology but a corporate one, the ideology of the professional military. They're reared in the culture of their service branch, build careers around war-fighting doctrines that are often outdated by the time they become heads of their services. They have an understandable tendency toward risk aversion and an equal tendency to conflate the interests of their services with those of the country. Civilians bring a fresh set of eyes to the problems of fighting wars. They tend, in short, not to be blinkered by preconceived notions and intellectual rigidity.

But if the civilians themselves are hidebound ideologues, then much of the benefit of strong civilian control is lost. It's just the blind leading the blind. And in Iraq that could get us into a heap of trouble.

Shares