At an early screening of his groundbreaking 1971 film "Sweet Sweetback's Baad Asssss Song," Melvin Van Peebles sat in a theater observing an all-black audience's reaction. Toward the end of the movie, as the eponymous antihero of the film was cornered by the "pigs," Van Peebles recalls hearing an old black woman mutter: "Let him die, let him die." She didn't want Sweetback delivered into the hands of the white police. When Sweetback escaped -- with the proclamation, "a BaadAsssss nigger is coming back to collect some dues!" -- Van Peebles remembers a stunned silence and then the audience erupting. "Nobody could believe he had survived," says Van Peebles.

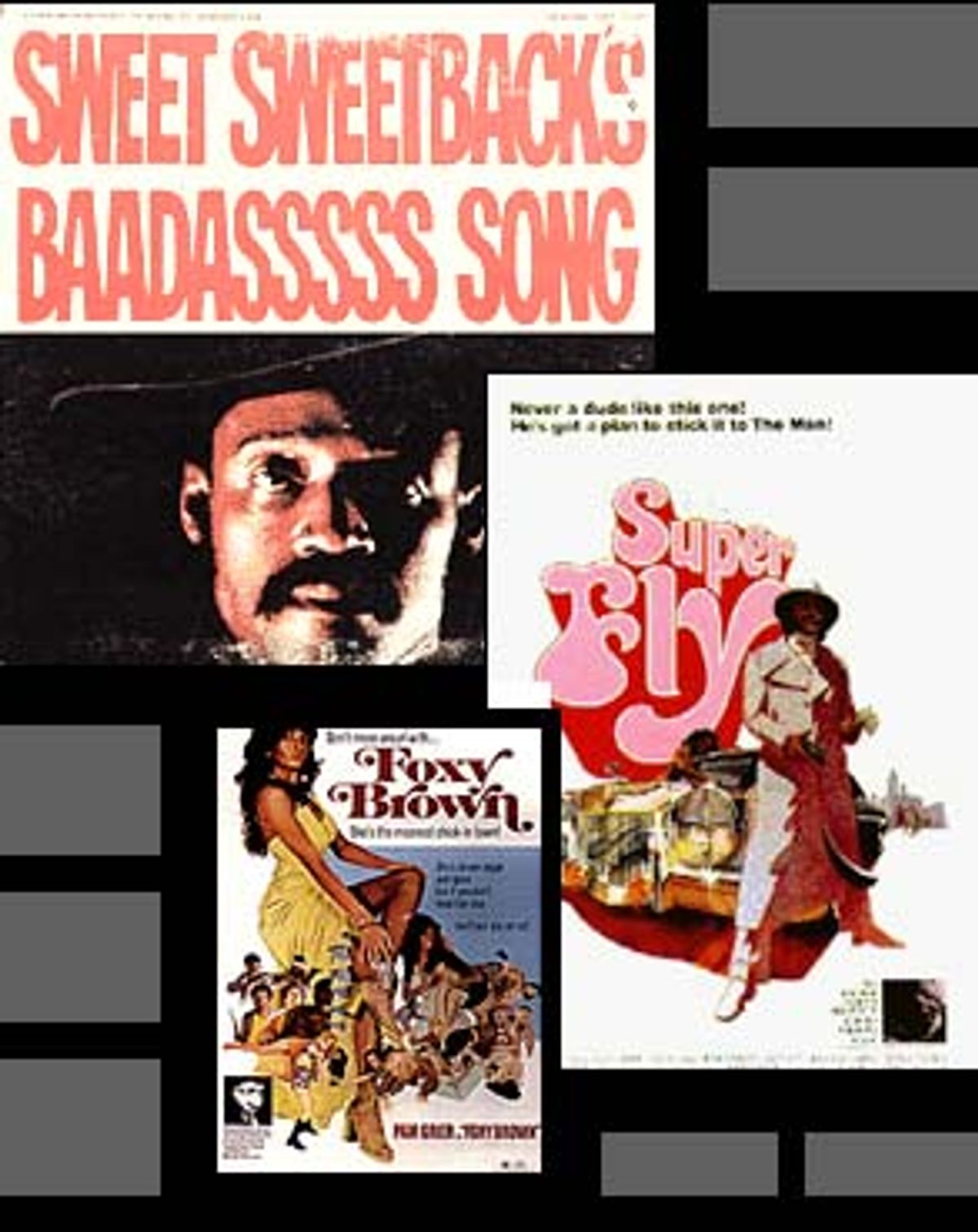

"Sweet Sweetback" went on to become one of the most successful independent films of its time, acclaimed by some critics for its formal innovation and embraced by African-American viewers for its "damn the Man" attitude. It was a major coup for Van Peebles, who directed, produced, distributed and starred in the film when Hollywood studios refused to touch it. The success of studio-released "Shaft" that same year, starring Richard Roundtree as the original bad mutha (shut yo' mouth), helped usher in a new wave of films targeted at blacks -- eventually labeled blaxploitation flicks.

"BaadAsssss Cinema," a documentary by British filmmaker Isaac Julien, is a tribute to the period when action heroes talked jive and grown men bowed to a sister with razorblades in her hair. The film premiered last week and airs several more times this month on the IFC cable network as part of a mini-festival featuring the seminal blaxploitation works "Shaft's Big Score," "Superfly" and "Foxy Brown." (Check your local cable listings for times.)

Three decades after blaxplo icon Pam Grier first put her high-heeled foot in some sucka's groin, Julien tracks down Grier, along with other key players like Van Peebles, for an affectionate reappraisal of the genre. Julien assembles 13 interviewees who act as jury, witnesses and defendants in the case for blaxploitation's cultural relevance. These include actors Grier, Fred "The Hammer" Williamson and Gloria Hendry, filmmakers Quentin Tarantino, Van Peebles and Larry Cohen, cultural critics bell hooks and Elvis Mitchell and former Black Panther Afeni Shakur (mother of Tupac).

Mixing archival footage, film clips and commentary, "BaadAsssss Cinema" examines blaxploitation's appeal for inner-city audiences: the ghetto-fabulous threads, lavish soundtracks, hyper-sexed scripts and comic book-style protagonists. Clearly blacks were hungry for on-screen representation that diverged from the bug-eyed shufflers of yesteryear or the impeccably high moral standards of Sidney Poitier's characters. Shaft and Sweetback may have been on different ends of the social spectrum, but they both raised a middle finger at the establishment.

"BaadAsssss Cinema" describes how many of the films made political statements beyond the visceral thrills; even the story of a drug pusher named Superfly had an underlying social critique driven home by Curtis Mayfield's score. Still, blaxploitation was a genre laden with double standards and quadruple entendres. While offering blacks their own heroes, they glamorized the violent lifestyles and sexual stereotypes many African-Americans longed to escape in real life. The films were especially problematic when it came to the treatment of women.

With hair by Angela Davis and body by Russ Meyer, Pam Grier's characters epitomized much of the conflict and contradiction inherent in the genre. The blaxplo female fire was clearly ignited by the feminist movement, yet the films primarily exploited the actresses' pneumatic charms. In "BaadAsssss Cinema," Grier acknowledges that her "whup-ass sista" persona reinforced some negative stereotypes about black women and explains how she tried to rise above the material. She laughs wryly, recalling how seriously she took her roles. "I thought it was 'Gone With the Wind,'" she says. "I was going for an Oscar."

But there would be no gold statuettes for the blaxploitation bunch, many of whose careers bottomed out like a pair of old flares in the mid-'70s. By then, with the release of increasingly dire vehicles like "Blacula" and its sequel, "Scream Blacula Scream," the movies had gone from sublimely ridiculous to blatantly moronic. As "Black Caesar" director Larry Cohen notes, "Most films are bad, but they abused the privilege." Audiences lost interest, Hollywood cut off funds and a backlash led by the NAACP was in full force.

"BaadAsssss Cinema" shows clips of the Rev. Jesse Jackson in a power 'fro and dashiki railing against the denigration of African-Americans on celluloid. The problem with the NAACP's attack, says Samuel L. Jackson, is that they never offered any viable alternatives. Thus the death of blaxploitation left something of a black hole, with no real black cinema emerging as a force again until the mid-'90s, with the wave of boyz-in-the-hood flicks that became known, ironically enough, as "gangsploitation." Gloria Hendry, star of "Black Belt Jones," talks emotionally about the sense of falling into an abyss after "blaxploitation saved Hollywood and when they got through with us, they dropped us."

Nonetheless, the BaadAsssss decade left an enduring legacy in both black and mainstream pop culture. Blaxploitation imagery lives on in everything from Snoop Doggy Dogg videos to "Austin Powers in Goldmember." Some actors have been able to make a comeback, such as Pam Grier, whom Quentin Tarantino treated with the utmost reverence in "Jackie Brown." Although Grier did not make it onto Halle Berry's infamous Oscar thank-you list, Berry has been touted to play Foxy Brown in a forthcoming remake.

In "BaadAsssss Cinema," Julien makes a persuasive argument for learning to appreciate blaxploitation on its own terms. Far from exhaustive, his documentary is more like Blaxploitation 101 for novices and casual fans, offering plenty to entertain and stimulate discussion, but little new for serious enthusiasts. "BaadAsssss Cinema" is the latest in an eclectic body of work exploring racial and sexual politics, and art from an outsider's perspective. Julien's best known films include "Looking for Langston," a stylish docu-dream on Langston Hughes that famously outed the late Harlem poet, the feature "Young Soul Rebels," set in 1980s London, and "The Long Road to Mazatlán," a homoerotic portrait of the Wild West that was nominated for the Turner Prize, the United Kingdom's most prestigious arts award.

Julien, who studied filmmaking in London at Central St. Martin's School of Arts, says he shoots his movies as if he's painting. In "BaadAsssss Cinema," he paints from a bold palette but rightly uses the lightest touch and knows exactly when to step back from the canvas. A visiting professor of Afro-American studies at Harvard, Julien continues to be an influential force in experimental film. Salon caught up with him by telephone while he was on vacation in Aspen, Colo., to talk about black cinema and the BaadAsssss mystique.

What attracted you to making a film about blaxploitation?

There was this fantastic book, "What It Is ... What It Was!" [by Gerald Martinez, Diana Martinez and Andres Chavez], which had interviews with all the different stars from that era, so that was probably what got me interested at first. Then I was teaching a course on blaxploitation at Harvard, on the invitation of Henry Louis Gates, and I realized there was no context for assessing films from this era. So this documentary in some ways was an attempt to put the fun back into film history and give recognition to what was one of the major periods in Hollywood cinema.

What would you say defines a blaxploitation film?

They're considered B movies, but they're really an amalgamation of different genres, including kung fu films, Westerns, horror, pulp, comedy -- although on the whole their main focus is black action films of the '70s. Of course, there's a whole other cinema of the period, films made by people like Charles Burnett and Julie Dash, which I think could be the subject of another documentary about [black] independent films. But I wanted to focus on blaxploitation films as part of '70s Hollywood history, films that have been pushed to the margins when they should be part of the official canon.

Why has there been such a renewed appreciation for this genre?

Blaxploitation's long afterlife, I think, is due to the fact that it was a repressed genre and it's only belatedly recognized as a genre within its own right. Some of the energy of the civil rights movement and the success of hip-hop culture were pivotal to its longevity. It's been very influential, even cropping up in new films like "Undercover Brother" and "Austin Powers in Goldmember."

I'm more interested in the darker aspects, like "The Bus Is Coming" (1971) and even some of the subtext in "Coffy." There's another film, "The Spook Who Sat by the Door" [in which a CIA-trained black man foments a new American Revolution]. So while they're great fun, there's also this serious angle, and I think that Quentin Tarantino, in "Jackie Brown," was able to give a serious reassessment of this genre. In his hands, it matures into a sophisticated thriller with film noir touches, even though it has the same motif as blaxploitation-era movies.

You included a sequence on the "N-word" debate in "Jackie Brown." I found it frustrating that, despite such a strong central performance by Pam Grier, so much focus went to how many times Tarantino used that word.

I think Tarantino's such a good scriptwriter [Tarantino in "BaadAsssss Cinema": "My dialogue's not poetry, but it's close"] that he was able to capture the vernacular which some others thought was a political issue. Obviously we listen to hip-hop and hear that word, and maybe it's flavored differently because of the music and rhythm, but as a trope of black culture it's alive and well.

I think the debate got so heated because cinema is a visual medium and we've had a problematic relationship with the way we've been represented on screen. But basically it's a reactive position that produces a safeguard in which black people always have to "behave" in the movies or risk coming under attack. There begins to be a clash with genre questions, because genre demands authenticity. Obviously if we didn't deal with that question in the film, people might think we're afraid to talk about it. But the real debate should be about the culture capital of black stars. Obviously Tarantino helped boost John Travolta's career, but even after "Jackie Brown," Pam Grier hasn't had the same kind of opportunities, and we all know why that is.

What do you think of casting Halle Berry in the Foxy Brown remake? Can Berry kick butt?

[Laughter.] It could work but I hope it's serious rather than just comedic. You have all these layers in the films, but what happens is that people always emphasize the comedic. Also, I hope it's not just about Halle taking her clothes off.

Would you say that the civil rights activists protesting blaxploitation not only missed the political subtext of a lot of these films, but also underestimated the audience who actually got the message, not just the hype?

I think that's absolutely the case. I think they greatly underestimated the audiences who were really quite sophisticated on many levels. Obviously there's a tradition of campaigning groups speaking on behalf of the public, but I think this contestation was about power, and that misfired on the actors and the artists. Of course, there are issues to be dealt with around the negative images of black culture and black women, but their analysis doesn't go far enough to touch on the complexity of these works.

For instance, a film like "Superfly" is really a comment on the failure of the civil rights movement. Here's this character who wants to do the right thing, but he's left with few options. The filmmakers are consciously playing with the genre of gangster movies but also providing a critique -- in "Superfly" this comes through in the soundtrack by Curtis Mayfield.

I love the way you used and referred to music in the documentary. Music has been a significant part of your own work, both as soundtrack and also as subject.

Sound is very important -- it's almost everything. The way someone like Melvin Van Peebles got Earth, Wind and Fire to do the soundtrack and then released it months in advance of the premiere of "Sweet Sweetback" was ingenious. It became a very Hollywood method of promoting movies. Music is very important in relation to blaxploitation and I'm always interested in the use of music to perform social commentary. So in that sense "BaadAsssss" was perfect, for me to be able to explore a black idiom that is so much part of the cinema. It's as big a star as the actors, if not bigger.

The documentary is open-ended but has a distinct narrative thread. Did you have a particular theme in mind when you started filming?

From reading the interviews with actors I knew I wanted to focus on the artists, who are always the ones on the firing line -- everyone from Pam Grier to Halle and Denzel today, they're the ones who feel the heat. One of the things that surprises you in making documentaries is the ways people react to what seem to be the most innocent questions. And you always have to be willing to go with things which at first may seem inconsequential but can move your film in a totally new direction.

Were there any surprises during the interviews?

I think it was Fred Williamson who really blew me away. He's someone who's tried to keep a certain visibility in film, yet he put himself on the line because he felt he had nothing to lose. Fred refers to Hollywood as a plantation system and says people are working on islands. Unlike the music business, there's no unifying force and that's one of its great failings.

Gloria Hendry's comments on her swift ascent and even swifter fall are very affecting.

Gloria Hendry's story is really the subject of the film. Although there were major stars, it's really about someone like her who is still fighting to this day for recognition. Yes, under the slapstick and comedic aspect, there is a painful, moving story behind it all.

You first experienced these films as a teenager. What, if anything, have you inherited from blaxploitation as a filmmaker?

I'm one of the generation of filmmakers whose work is antithetical to blaxploitation. But one of the things I've learned while making documentaries is that some of the motifs live on because they have a certain power. It's interesting, though, that there are hardly any black indie filmmakers who have worked with someone like Pam Grier, because they were, in a way, the bête noir of black independent filmmaking. But it had such a primal, pivotal effect on me as an audience member. These films weren't connected to art in the sense of high culture, but they are art in terms of popular culture.

You seem to have moved further into art-house cinema, with video installations and such. Are you interested in doing another mainstream feature down the road?

I'd only want to make the feature I want to make. In the art world, the idea comes first, so for me it's a good place for an appreciation of the complex nature of my subjects. I just saw "Road to Perdition" and I thought it was fantastic. Sam Mendes did a wonderful job, but very few black filmmakers have access to that kind of material, and I'm always struggling with funding issues.

There seems to be a growing overlap between Hollywood and the indie scene. Is there any such thing as independent cinema any more?

Independent cinema is a budget of $15 million with a star actor. Real indie cinema doesn't exist anymore. Its appropriation by Hollywood has hurt the genre, because we never got to fully realize the ways in which cinema could develop outside the norm. But times shift, films change and now a lot of Hollywood mainstream films have taken on an independent approach, which I suppose is a good thing.

Much of your work explores homoeroticism and homophobia in black culture. I've always thought there could be a gay subtext to some blaxploitation films.

Absolutely. In fact, I'm working on a three-screen piece, a short film called "Baltimore," which I'd describe as blaxploitation meets the art world. It's still in development, but it does have an interesting subtext that explores questions of homoeroticism in blaxploitation. I'm looking for a famous blaxploitation actor to take the lead. Blaxploitation films are overtly camp and they do have appeal for a crossover audience. But you know so many of these aspects are repressed, and I think maybe there are several documentaries to be made on the subject.

Afena Shakur was an interesting interviewee. Why did you select her?

We thought she was a fantastic subject for the historical trajectories and all the contexts of blaxploitation: from the black power movement to modern-day hip-hop with her son Tupac, who was also an actor and who also starred in gang movies and had that duality of dark and light at play. We also thought she was interesting as an audience member in her own right, someone who watched and enjoyed blaxploitation cinema when it first broke through.

I thought her comment about how the Black Panthers only had "perceived power" but no actual power was a critique that could be applied to so many aspects of black culture, including blaxploitation.

Yes. In a sense the promise of black action films of the '70s was that they would empower the actors and artists involved, that there would be more roles and opportunities and the doors would break open so that other genres and traditions could come through, but that never happened. In a way, it's a promise that has yet to be guaranteed.

Shares