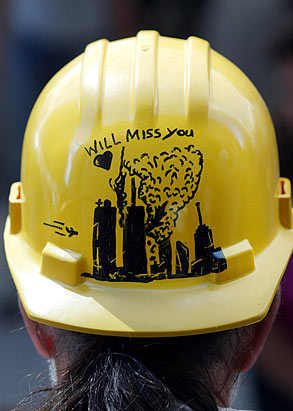

Jill Gatsby, 30, painted a 1964 VW bus to look like a fire truck and drove here with her girlfriend from L.A., stopping in firehouses in 17 states to sing folk songs. Dressed in an old fire suit, dyed yellow hair beneath a flag-stripped bandana, Gatsby marched with New York’s firemen from the Bronx to Ground Zero, then proceeded to Tompkins Square Park to play for a crowd that included overgrown punks on tiny bicycles, two enthusiastic middle-aged black women, a pretty Hispanic transsexual, a fading movie star and a drunken 5-foot-tall Asian man doing a delirious drunken dance based on Tae Kwon-Do.

New York did the impossible on Wednesday — it reclaimed Sept. 11 from media mawkishness and political opportunism. Setting out this morning to cover the day’s events in Manhattan, I found that impossible to imagine. On TV, the past few days have been an orgy of sanctimony, with anchors relishing every brutal detail of the year-ago slaughter even as they spout the saccharine slogans of commemoration. Meanwhile, the president had already announced his plans to hijack the anniversary of the attack on this city to push policies that are anathema to most of its residents. Downtown would be flooded with people who lost nothing that day, but who burned to buy made-in-China flags and tasteless T-shirts and enjoy a few moments of delicious mournful melancholy.

But when I turned off the TV and ventured into Manhattan, I found it had bloomed with art and protest, music and grief. The September Concert Foundation organized hundreds of free performances all over the city. There were punk bands in Tompkins Square Park, DIY group installations in Union Square, Mozart’s Requiem at Juilliard. Joe McNally’s magnificent 9-foot tall photographs of 9/11 survivors were displayed in a Rockefeller Center tent. In city squares, thoughtful political discussions were carried out in chalk on the pavement. People in the Village wore “New Yorkers Say No To War” T-shirts.

And everywhere — on coffee shop benches, at the Astor place subway, on the steps of Saint Patrick’s — people sobbed quietly, far from the braying of network TV.

At first the day gave little indication it would be so inspiring. Near ground zero, the tourist hordes, looky loos of grief, huddled behind barricades, while a nearly equal number of journalists and photographers snapped their earnest shows of sorrow. On the corner of Trinity and Liberty, a well-scrubbed man with a reporters’ notebook asked an old woman, “Is it drudging up painful memories? Is it bringing closure?” A very large woman wore a T-shirt with a minute-by-minute chronology of last Sept. 11, under the excited headline, “The Worst Day in American History!”

Every few feet there were bright-red “Prayer Stations,” and well-scrubbed missionaries accosted passersby to ask, “Is there any way that we can pray for you?” Doomsayers milled about, one muttering, “For the wages of sin is death …” A group of children in fatigues, shepherded by an adult in Green Beret dress, carried toy rifles. And when a victim’s family member passed by on the way to lay flowers at the site, heads everywhere craned for a peek, the survivors’ desolation making for a sharp contrast with the rubbernecking breathlessness of the crowd.

Gov. George Pataki’s reading of the Gettysburg Address also struck a weird note, especially the line, “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure.” The quote carried a sinister hint that those who disagree with the White House line are traitors, a threat to the nation’s endurance.

But things changed as soon as former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani took the microphone, to screams and cheers from the crowd. As Yo-Yo Ma played a mournful cello, Giuliani began reading the names of the dead — Muslim names, Jewish names, Spanish names, Italian names, Anglo names. Suddenly, the commercial tawdriness that’s blighted the area around the disaster seemed to dissipate, and a true, quiet sadness settled on the suddenly reverential crowd. The names echoed from radios all over lower Manhattan, filling the air with an unadorned reminder of loss.

Such deep, plain sadness mingled with a glowing love of the city throughout New York all day long, nowhere more so than at Union Square. A year ago the park was turned into a spontaneous and devastating memorial to the dead and missing; this year, someone set up tables with hundreds of pieces of paper and colored markers for people to leave messages on a giant wall. Beneath it, the messages continued in chalk as people argued about the world.

Someone had written, “Should we wait for a smoking gun in Baghdad? Or for another Smoking City in North America? Tough Decision.” Beneath it, someone riposted, “The tough decision is to choose peace and end suffering.” A poster on the wall walked a middle path: “Replace Bush with Kerry. But first replace Saddam Hussein with 6 feet of fresh soil.” And someone else quoted Gandhi, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.”

40-year-old Kim Wylie stood before the makeshift memorial on her way to church. She wore a fuchsia “I Love New York” tank top, and she was sobbing. “Today is another level of mourning,” she says. “The first few months were incredibly raw. This feels like that all over again. But being in New York feels great. It feels so safe here. I feel so honored to live here. It really is a privilege.”

One irony of Sept. 11 is the fact that for a year now, the assault on New York has been used as a perverse cudgel to attack much of what this city stands for — debate, dissent, internationalism, progressivism. Jerry Falwell blamed the attacks on “pagans,” feminists and gays — crucial elements in New York’s ferment — and though he later apologized, he never became a pariah like, say, Noam Chomsky. Ann Coulter has been feted on the talk shows even as she gleefully thirsts for the blood of the metropolis’s liberals.

I think that’s what Paul Auster was reacting to when he wrote in the New York Times last Saturday, “Not long ago, I received a poetry magazine in the mail with a cover that read: ‘USA OUT OF NYC.’ Not everyone would want to go that far, but in the past several weeks I’ve heard a number of my friends talk with great earnestness and enthusiasm about the possibility of New York seceding from the union and establishing itself as an independent city-state.”

God knows I’ve had the same discussion a dozen times this year, but the mistake I made was to let the most benighted corners of this country foist its definition on me. In dismissing the anniversary of Sept. 11, I had mistaken the media representation of memory for the thing itself. Last year’s loss, and the solidarity born from it, turned out to be too vital to be sucked dry by the idiot bleating of politicians or pundits.

To me, the thousands of passerby who affixed political messages to a giant wall in Union Square are more American than officials who warn we should watch what we say. What’s worthwhile about my America is all the bleeding-heart liberal middlebrow stuff that drives the right crazy. It’s the sweet earnest humanists at the Society for Ethical Culture on 64th Street who hosted musical collaborations between Arabs and Jews. It’s writers like Francisco Goldman and Paula Fox giving free readings on the steps of the Brooklyn Public Library. It’s the lefty kids who camped out overnight in Washington Square and left behind hand-scrawled signs with slogans like “Bull Dykes Not Missile Strikes.”

Later in the day, Jill Gatsby looked up from the Tompkins Square bench where she was napping and said, apropos of nothing, “I’ve been across the United States. New York City is America.” An obvious thing to say, perhaps a maudlin thing, but also obviously true. And if New York is America, then America is worth grieving for, and worth celebrating. By reclaiming Sept. 11, New York also took back the country, if just for a day.