It's no secret that Bradley Smith opposes almost any effort by the federal government to regulate campaign finances. He's written, spoken and testified before Congress on his belief that campaign finance laws unconstitutionally restrict speech, help incumbents while hurting challengers and generally cause more problems than they solve. He has even written a book titled "Unfree Speech: The Folly of Campaign Reform."

After arguing for years that election reform laws should be repealed, the former law professor today finds himself in a curious position: He is a member of the Federal Election Commission, charged with enforcing the U.S. campaign finance laws that he has long opposed. And with a majority of his colleagues on the six-member panel, he appears to be working to systematically undermine the McCain-Feingold campaign reform law, which was supposed to impose dramatic new limits on the power of "soft money" in American campaigns.

Smith and the other commissioners in his camp say they are simply writing the rules required to make the law's definitions precise, resistant to court challenges and discouraging to frivolous or politically motivated attacks. But after a series of controversial votes last June -- and with a new rule-making session just beginning at commission headquarters in Washington -- critics say the commissioners have adopted a set of regulations with such narrow definitions and significant exemptions that the soft money floodgate will remain open, or at the very least, easy to circumvent.

Sen. John McCain and the other sponsors have blasted the FEC's interpretation of the law, charging that the commissioners have ignored the will of Congress and exceeded their authority. "Their conduct has been the most disgraceful I've seen in 20 years in Congress," McCain, an Arizona Republican, told Salon. "They're clearly violating both the intent and the letter of the law. They say they are writing their regulations on the basis of constitutionality. That's not their job. That's the job of the courts."

Sen. Russell Feingold, D-Wis., expressed similar frustration in a statement to Salon. "With its eyes wide open and in the face of strong criticism from both the sponsors of the law and groups that support it, the FEC has opened loopholes in the new law before it even takes effect," he complained. "This is not a legitimate exercise of regulatory authority and something must be done about it."

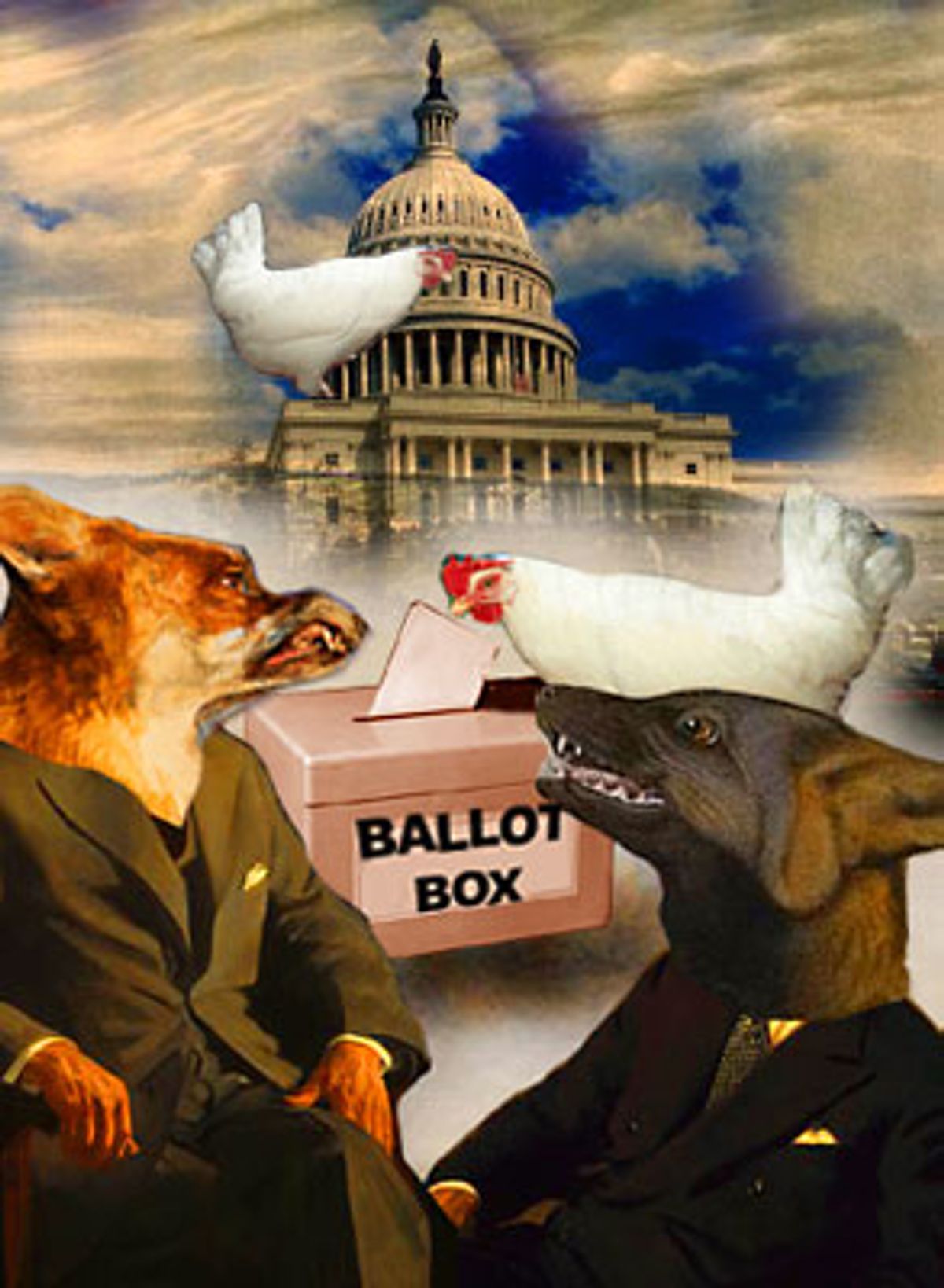

For years, critics across the political spectrum have warned with increasing urgency that hundreds of millions of dollars in unregulated "soft money" was corrupting the political process, allowing free-spending special interests to buy access and influence with lawmakers that other people or groups could never match. McCain-Feingold was intended to help purify the process by clamping down on the riches that get funneled to political parties and political action committees every election cycle.

While McCain and his allies may be dismayed by the commission's actions, they shouldn't be surprised. According to a Salon investigation, the commission has been criticized almost since its inception in 1974 as a poorly camouflaged tool of the two major political parties. Critics derisively call it the Failure to Enforce Commission, or, more simply, FECkless. In a two-year study released this May, a task force of public policy specialists, former commission officials and legal experts found the agency so flawed that they recommended it be scrapped and replaced with something less political and, presumably, more functional.

Now, to the chagrin of critics, this little-known but high-powered agency is slamming headlong into the most sweeping campaign finance law in almost 30 years. This week, the commission turned its attention to revising rules for political advertising -- a process which, critics say, will likely mean finding a way to continue the abuses that plague campaign advertising in federal elections.

"If there's one thing the FEC has done over its lifetime, it's protect the political parties," says Paul Sanford, a former commission attorney and current head of FECWatch, an oversight group run by the nonpartisan Center For Responsive Politics, a nonprofit based in Washington.

To be sure, groups ranging from the Republican National Committee, the National Rifle Association and antiabortion groups to the AFL-CIO and the American Civil Liberties Union have filed suit over various provisions of the bill. And the commission itself defies easy partisan breakdown -- two veteran commissioners appointed by President Reagan, the conservative Republican icon, are the strongest reform advocates on the panel.

But the majority of FEC commissioners today are political ideologues or party insiders who often appear more intent on catering to the parties' interests -- and the interests of big money -- than in protecting the public's interest in having fair and honest elections. At least four of the commissioners -- Chairman David Mason, Vice Chairman Karl Sandstrom, Smith, and Michael Toner -- have expressed opposition to current campaign finance law. And three of them -- Mason, Smith and Toner -- openly opposed the bill as it moved through Congress. Only the Reagan holdovers, Danny McDonald and Scott Thomas, seem to support the laws they are responsible for enforcing.

But if the will of the membership seems to contradict the spirit of federal campaign laws, critics say, that may be by design. Fred Wertheimer, executive director of the watchdog group Democracy 21, says the problem is simple: The commission was supposed to be a paper tiger, and it is. The members, who are paid a set income of $130,000 a year, are chosen by the same politicians they are supposed to regulate. Commissioners like Smith are selected for their ability to soften the campaign laws and preserve the parties' power, Wertheimer says, not for their ability to aggressively enforce the law.

"You don't have people with enforcement backgrounds being appointed," Wertheimer says. "You don't have people who come from state ethics agencies or other ethics backgrounds appointed to this commission. You have people who are sent there with an implicit if not explicit mandate to protect the members of Congress and the political parties who sent them there."

Reformers had been pushing federal lawmakers since the early years of the 20th century to regulate campaign spending and practices, but with little effect. That changed with the 1971 Federal Election Campaign Act, the law that sets campaign contribution limits and requires timely contribution disclosures from federal candidates.

The law was amended after the Watergate scandals in 1974, giving birth to the Federal Election Commission, which is charged with investigating campaign abuses and, when it finds violations, either seeking fines or recommending that the Justice Department pursue criminal investigations. Under the law, the commission is the only body allowed to file suit against federal campaigns.

The concept of "soft money" was born in 1978, when the commission issued an opinion that allowed state political party activities affecting both state and federal races to be paid for with a mix of regulated and unregulated funds. A year later, the commission cleared the way for the national parties to raise unregulated funds for similar mixed state-and-federal campaign activities. Enron, for example, would be allowed to give millions to various state or national party committees and not have the donations be covered by the strict federal donation limits that presidential campaigns are subject to. These party committees can then spend the money on advertising, facilities, get-out-the-vote drives or other activities that end up benefiting the party's presidential candidate.

"Gradually," says Commissioner Thomas, "the party committees figured out that, hey, you've got a lot of states where you can give an unlimited amount to a party committee. Corporations can give, unions can give ... Very influential federal legislators got involved in raising the soft money and it became suddenly a real players' game, with huge amounts of money coming in. And the FEC, stemming from that 1978 decision, is largely responsible for getting it going." Later, Thomas says, Congress reinforced this game with legislation that officially sanctioned such activities.

According to the campaign watchdog group Common Cause, during the first 18 months of the current election cycle, national parties raised over $300 million in soft money. That is an 18 percent increase over the amount raised in the first 18 months of the 2000 election cycle (a presidential cycle) and nearly three times the amount raised in the last comparable election four years ago, according to the group.

Critics identified problems in the system years ago, but early efforts to reform the commission were undermined in Congress. The commission originally had been structured to avoid partisan enforcement actions. No more than three of the six commissioners could be from any one party, and a four-vote minimum was required for any commission action. At first, the president was given two appointments, with two going to the majority leadership in Congress and two others to the minority leadership.

In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled that the process violated presidential appointment powers. Because the Federal Election Commission has the power to administer and enforce the law, the court ruled, commissioners are officers of the United States, similar to top executives at the FBI or the Securities and Exchange Commission. Therefore, the court said, the election commissioners have to be nominated by the president. Congress then restructured the appointment process to a more traditional formula in which the president made the appointments and Congress approved them. Practically, though, little changed. The president usually defers to congressional leadership for four of the seats, and Congress has been known to retaliate if the process doesn't run smoothly.

Commissioner Bradley Smith is a contemporary case in point.

Smith, a law professor, had written numerous articles against campaign finance regulation and reform in journals and newspaper editorials, and found himself a favorite witness of reform opponents on Capitol Hill, most of them conservative Republicans. Eventually, Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., approached Smith about an appointment to the commission. McConnell is among the most outspoken critics of campaign finance reform in Congress, and has already filed a lawsuit attacking McCain-Feingold as unconstitutional.

Mississippi Republican Sen. Trent Lott, then the majority leader, sent Smith's name to President Clinton for appointment. Clinton initially balked at putting such a strong critic of campaign finance regulation on the commission, but when Lott delayed the confirmation of Clinton's choice for U.N. ambassador, Richard Holbrooke, and threatened several judicial appointees, the president relented.

Clinton thereby found himself in the odd position of simultaneously nominating and disparaging Smith. "I don't like it," Clinton told reporters in a 2000 news conference covered by the Associated Press. "But I decided that I should not shut down the whole appointments process and depart from the plain intent of the law, which requires that [the commission] be bipartisan and, by all tradition, that the majority make the nomination."

Wertheimer and his group, Democracy 21, put together a task force of experts in 2000 to study the commission's history and problems. Members of the team came from a range of backgrounds and included experts from such places as the Brookings Institution, Harvard Law School, Common Cause, and one former federal election commissioner. In its findings, the task force detailed a series of spectacular enforcement breakdowns. It also named the politicized nature of the appointment process as a key problem.

While the commission this week announced record fines against players in the 1996 Clinton-Gore campaign for illegally soliciting foreign money, that action may have been a cover for mounting attacks against its leniency. Critics say such enforcement is the exception and not the rule.

One of the more serious debacles took place when the commission investigated both the Clinton-Gore and Dole-Kemp presidential campaigns' use of television advertising in the 1996 campaign cycle. The commission's general counsel found that both campaigns had run ads illegally coordinated between the candidates and the political parties, which had been paid for with soft money. The Clinton-Gore camp alone used over $47 million in illegally coordinated campaign ads, according to the report. Despite strong evidence of wrongdoing, and the recommendations of its own staff, the commission failed to pursue charges against either campaign. Even a fine, critics point out, would have discouraged such illegal coordination in the future.

"Those kinds of things involve enough spending that it really could have impacted the election result," says Thomas, who voted in favor of enforcement. "And yet the commission ... did nothing."

Even as the Democracy 21 investigators were at work, ambitious bipartisan measures to overhaul the system were being advanced in Congress by Sens. McCain and Feingold and by Reps. Christopher Shays, R-Conn., and Martin Meehan, D-Mass. McCain and Feingold waged an epic seven-year battle to get their landmark campaign finance reform bill past fervent opposition. In late March, the supporters outmaneuvered the opponents for a final time, winning legislative approval for a bill formally known as the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. Public support for the measure was so strong that President Bush was compelled to sign it into law despite his earlier opposition.

The main thrust of the measure was to choke off soft money. The bill prohibits federal candidates and national parties from raising or spending soft money, even for state party activities. The president, for example, is prohibited from asking rich donors to give contributions over $25,000 to state party committees. Additionally, the law puts a check on state party usage of soft money to influence federal elections -- money used for advertising mentioning a candidate, or get-out-the-vote drives, for example. The bill also places new restrictions on the kind of advertising that can be done by special interest groups close to an election. The bill has other provisions, such as raising the maximum individual restriction limits and further tightening restrictions on foreign donors, but the heart of the law is its attack on large, unregulated contributions.

But while a legal challenge was inevitable, a challenge from the Federal Election Commission was predictable, too. The bloc of four reform opponents was in place and they were facing their biggest challenge -- and a cursory review of their résumés makes clear that even Bush's signature was no guarantee that the law would be put into effect.

- Bradley Smith has never been a Republican activist, but as a professor at Capital University Law School in Columbus, Ohio, he gained notice in Washington for his frequent articles blasting campaign finance reform. McConnell views his recruit as an ideal choice for the commission.

"Professor Smith is a First Amendment scholar and the most qualified commissioner in the history of the Federal Election Commission," McConnell said in a prepared statement. "His constitutional expertise is particularly needed at an FEC that has a dismal string of losses in federal court. I believe the FEC needs at least one commissioner who understands the First Amendment and respects Supreme Court precedent."

Smith sees himself as a civil libertarian pulling for the underdog. In his view, campaign finance regulation restricts speech, is vulnerable to loopholes and helps incumbents at the expense of challengers. In a commentary written for the Wall Street Journal in March 2001, after his appointment, Smith accused McCain and Feingold of a cynical ploy to silence critics with their bill's advertising restrictions.

Contrary to the findings of Democracy 21, Smith, like McConnell, says the commission has been too aggressive in the past, venturing into areas where it has repeatedly been struck down by the courts.

"I certainly wasn't chosen for my partisanship," he says. "I was selected because there was a great number of people in Congress who I think represent a great many people in this country who felt this commission had gone the wrong direction and needed a voice that would pull it back to the center."

- FEC Chairman David Mason was deeply involved in the Republican Party prior to his 1998 appointment. He served in both Ronald Reagan's and former President George H.W. Bush's defense departments, and has served on the staffs of several House and Senate members, all Republicans. He ran for the Virginia House of Delegates on the Republican ticket in 1982, but lost.

In a report for the conservative Heritage Foundation titled "Why Congress Can't Ban Soft Money," Mason made his objection clear: "Congress should recall that existing practices are direct responses to previous attempts to regulate political activity. As 'hard money' (direct expenditures on campaigns) was limited and regulated, activists simply changed tactics ... The real solution to the problem of soft money lies in minimizing, not expanding, government controls."

Mason did not return calls for comment.

- Michael Toner is the most recent commission appointee, taking the post during a congressional recess in March -- two days after Bush signed McCain-Feingold. Toner's choice represented a slight departure from the traditional appointment process, in that Bush chose him rather than support the Republican congressional choice, former commissioner Daryl Wold. But critics were hardly relieved by Bush's break from tradition. Like Smith and Mason, Toner has denounced campaign finance reform, though not as often or with as much furor. And he is much closer to the Republican Party apparatus.

Immediately before his appointment, Toner was general counsel at the Republican National Committee, which soon would file suit to overturn the reform law. Before that, he was general counsel on the Bush-Cheney presidential campaign. He also worked as a counsel to the Dole-Kemp ticket in 1996.

It was during his time with the Republican National Committee that Toner publicly opposed the McCain-Feingold bill. "Democrats are driving legislation that will put a stake through the heart of grass-roots and voter-education initiatives," he told the Associated Press in July 2001.

Like Smith and Mason, Toner has issued assurances that his views of campaign finance, and his relationship with the Republican Party, will not unduly influence his actions on the commission. In fact, Toner said in an interview that his involvement with the GOP is an asset to the commission.

"I think my having worked in the trenches, advising candidates, political staff, the RNC -- people who've had to deal with all these regulations -- about what they need to do [is] a healthy and positive perspective," he says. "You've got to tell people what they can and cannot do. The rules have got to be made as clear as possible."

- Democrat Karl Sandstrom was appointed in 1998. Before that he was chairman of the Administrative Review Board at the Department of Labor and served on the Subcommittee on Elections in the Democrat-controlled House during the late '80s and early '90s. He doesn't have the ideological baggage that his Republican counterparts do, but he has largely voted like them, shying away from strong enforcement action, refusing to pursue action in the Clinton and Dole television ad fiascos and asserting himself to water down McCain-Feingold.

Sandstrom's actions seem to stem from a belief that attempts at campaign finance regulation are so complicated that enforcing them is often impossible. His common refrain is that laws need to be made clear and "concrete" before they can be enforced.

"Before we can enforce the law the public must be made aware of what the law is," he said in a recent interview. "People active in politics are [sometimes] uncertain as to what the rules are. That is not a healthy situation. Either people proceed at some risk or they do not engage in political activity because they are fearful they might violate an uncertain standard."

The cautious approach and the narrow interpretations are frustrating -- sometimes maddening -- to their two colleagues, Scott Thomas and Danny McDonald. Both, surprisingly, were appointed by President Reagan, and both have been bluntly critical of the majority.

"I view my role as primarily trying to give my colleagues the courage to enforce the law as Congress intended," Thomas said in an interview. "At least from my perspective, commissioners are spending too much time trying to figure out ways not enforce the law, or to enforce it in a way that is focused only on rather insignificant little cases, and finding ways to drop the big cases."

Between now and year's end, the commissioners will preside over a complex process in which the rules of campaign finance reform will be drafted, studied, subjected to public hearings, reviewed, amended and then approved in a public vote. Thus far, only the rules on soft money have been reviewed and approved by the commissioners, but in that process, critics see a grim harbinger of things to come.

Initial drafts by the commission staff provoked only modest debate, and most controversies seemed to be quelled by the last proposed draft. But in the final session, spread over four days in June, the commissioners introduced and approved a set of amendments to the draft regulations that bloodied the law. "Watching the final soft money rule-making was like watching a stock market crash from the trading floor," says Paul Sanford of FECWatch.

The meeting was held in the Federal Election Commission's public hearing room in Washington, a room packed with commissioners, lawyers, staffers and an audience of more than 100. Those who attended watched a lesson in how fine-print changes in the law -- seemingly insignificant -- had the effect of a counterrevolution.

As drafted, the rules blocked federal candidates from raising or directing soft money, prevented national political parties or organizations related to them from doing the same, and generally curbed soft money's influence on federal elections. But scores of amendments were introduced, one at a time, each weakening the law, and many passing by the same 4-2 vote.

When the commissioners tried to settle on what it meant to "solicit" donations, the commissioners' general counsel, Larry Norton, offered a common-sense approach: Solicit means to "request, suggest or recommend" that a donation be made. Sandstrom flatly rejected that language, asserting instead that "solicit" means a candidate must explicitly "ask" for a donation. Norton shot back: "It doesn't seem to me to take a great deal of cleverness to ... persuade a person to make a contribution, without coming out and asking. I think this definition has the potential for great mischief."

The reform opponents mustered four votes to pass the amendment.

In its effort to stop national political parties from using shell organizations to get around the new law, McCain-Feingold states that such organizations, when created or run by the parties, would also be covered under the law. But Toner moved to open a potentially huge loophole: Any organization created before the law took effect Nov. 6 would be exempt, as long as it was no longer controlled by the party after that date.

Again, the reformers were incredulous. "[The FEC] will allow the parties to set up these organizations, and perhaps provide them with some funding, and then after November these groups can operate however they like, and they're not subject to the same soft money restrictions that apply to the parties themselves," Sanford says. "The rules are a recipe for them to do this. It's a big, giant sign in 6-foot letters that says: 'Do this.' And they've painted it on the Capitol dome. If party committees aren't doing this, they need to have their eyes checked."

And Sanford appears to be correct. The Washington Post reported just weeks after the meeting that the national parties were already moving to set up soft money shell organizations for use after November.

Toner counters that it's ridiculous to hold someone accountable under a law for things they do before the law takes effect. "What basically developed was a concern that people would be prosecuted next year for conduct that they're doing now that is legal under current law," Toner says. "If you're going to have a transition period, than what you're doing now, if it's legal under current law, should have no bearing on if it's legal next year."

When the June rule-making session was finished, campaign finance advocates were outraged. "You have so tortured this law, it's beyond silly," Commissioner Thomas, one of the Reagan-era veterans, told his colleagues. McCain and the bill's other sponsors agreed, and they blasted the commission's actions.

"The Federal Election Commission has taken upon itself the task of rewriting the newly passed McCain-Feingold/Shays-Meehan bill," the four said in a joint press release the day after the rules were issued. "This is not a role given to the FEC by Congress, or by the Constitution ... Many of the amendments adopted in the past two days simply ignore the law. They show that a majority of the FEC is willing to flout congressional intent and substitute its own policy preferences. The country deserves better, especially from an unelected body."

Despite such a dressing-down by the congressmen who created the bill, the four commissioners who rewrote it were unapologetic. "They don't understand the regulations that they're criticizing," Smith says of the sponsors. "At times they either don't understand their own bill, or they're trying to get the commission to do things that they didn't think they could put in their bill and get it through Congress."

Thomas disagrees. "I'd be happy to sit down with anybody at any time, and take the provisions of the statute and the legislative history and the comments we got, and show how the approach that my colleagues took doesn't coincide with the language or intent or the legislative history," Thomas says. "In virtually every occasion when that kind of an issue came up, four commissioners took the position that was: 'Let's interpret the law in a way that will allow more of the soft money to come in and continue.'"

McCain and the other sponsors will likely file a resolution in Congress seeking to have the rules overturned. They have also said that they are considering filing a legal action against the commission. But both avenues will be difficult at best. The resolution would need approval in both houses of Congress and would have to be signed by the president. A lawsuit will have to prove that the rules were "arbitrary and capricious," a standard that campaign finance advocates say can be achieved, but only after a long detour through the courts.

And even as McCain and the other sponsors pursue these efforts, the commission is likely to chip away at the law in different areas as it continues in the five other rule-making sessions that are likely to last until the end of the year. So far, the draft rules in areas like advertising appear to be far less controversial than the final soft money rules, but critics are mindful that most of the objectionable changes on soft money rules came at the last minute.

There is one bright light on the horizon for Sanford and other reform proponents: Sandstrom is set to be replaced in October by Ellen Weintraub, a former counsel to the House Ethics Committee and the wife of Feingold's legislative staff director; that change will almost certainly alter the balance of power. Bush approved the nomination only after McCain threatened to vote against Bush's judicial nominees.

Far from solving the commission's problems, however, the change may only result in gridlock. Many critics insist that the only way to really solve the problems of the Federal Election Commission is to disband it. The Democracy 21 task force recommended replacing the commissioners with a single, long-term administrator. That, the authors said, would force the president and Congress to appoint an executive who is more powerful and less partisan.

McCain says he may pursue some type of restructuring of the agency, in hopes that one day the campaign reform law will become what it was intended to be. "It took Russ [Feingold] and I seven years to get this law passed," he says, "and we're not going to quit. It may take another seven years to get it enforced properly, but we'll win over time."

Shares