When artist Laurie Hogin, 39, was a child, she lived in a suburb of New York adjacent to a 600-acre woodland. "It belonged to some old guy who just wasn't going to sell it," Hogin says, "so we had these woods to play in -- me and my two friends. It was a wonderful, safe place for us. We were all interested in what was then called ecology; we'd see foxes, deer, wild turkey, pheasant, we'd find mushrooms. But it was a ravine with a road above it and occasionally people would dump tires, garbage and 55-gallon drums. This outraged us."

Hogin expressed her outrage by drawing pictures of the woods with the tires, garbage and barrels scattered about, often giving the drawings to her fourth-grade teacher. "It was sort of an infantile form of protest," she says. It also was, and continues to be, an organizing metaphor for her life.

The pictures Hogin makes today -- startling, provocative, elegant (she calls them "parodies of opulence") oil paintings, some as large as 8 by 10 feet -- still focus on the environment, and on a variety of other cultural and political issues that are both pressing and controversial, which makes her work especially relevant right now. Given the powerful connection between the topics she takes up in her art and the current American dynamic -- not just between humans and a disappearing natural world, but between average folks and the corporate world, the ruling elite of capitalism -- what Hogin's doing, or attempting to do, is both important and, in many ways, amazing.

What sets her work apart is that she's one of the rare artists able to pepper her images with fierce commentary without coming off as strident or didactic -- partly because her paintings are often darkly funny, and partly because their appearance is so striking. Writing in the Chicago Sun-Times, critic Margaret Hawkins explained, "The reason Hogin can get away with her intensely intellectual subject matter is that her paintings are visually irresistible, inspiring a kind of optical gluttony that is then surprised in mid-gorge by the paintings' weighty subtext."

What Hogin does, and does brilliantly, is appropriate the seductive language of advertising and dress it in the lush, hyperrealistic style and technique of 17th century Dutch and Flemish painting in order to make scathing visual comment on contemporary consumerism, sexism, the trashing of nature and the inequities of the global economy. She seized on the idea of adopting the exacting style of the 17th century artists in service of her own trenchant, satirical observations because of the strong parallels she saw between their time and the present. The period, she says, "strangely mirrors our own times in [what author Simon Schama has called] its 'anxieties of superabundance,' attitudes toward class, citizenship, the family and the peculiar kinds of stuff people strove to acquire."

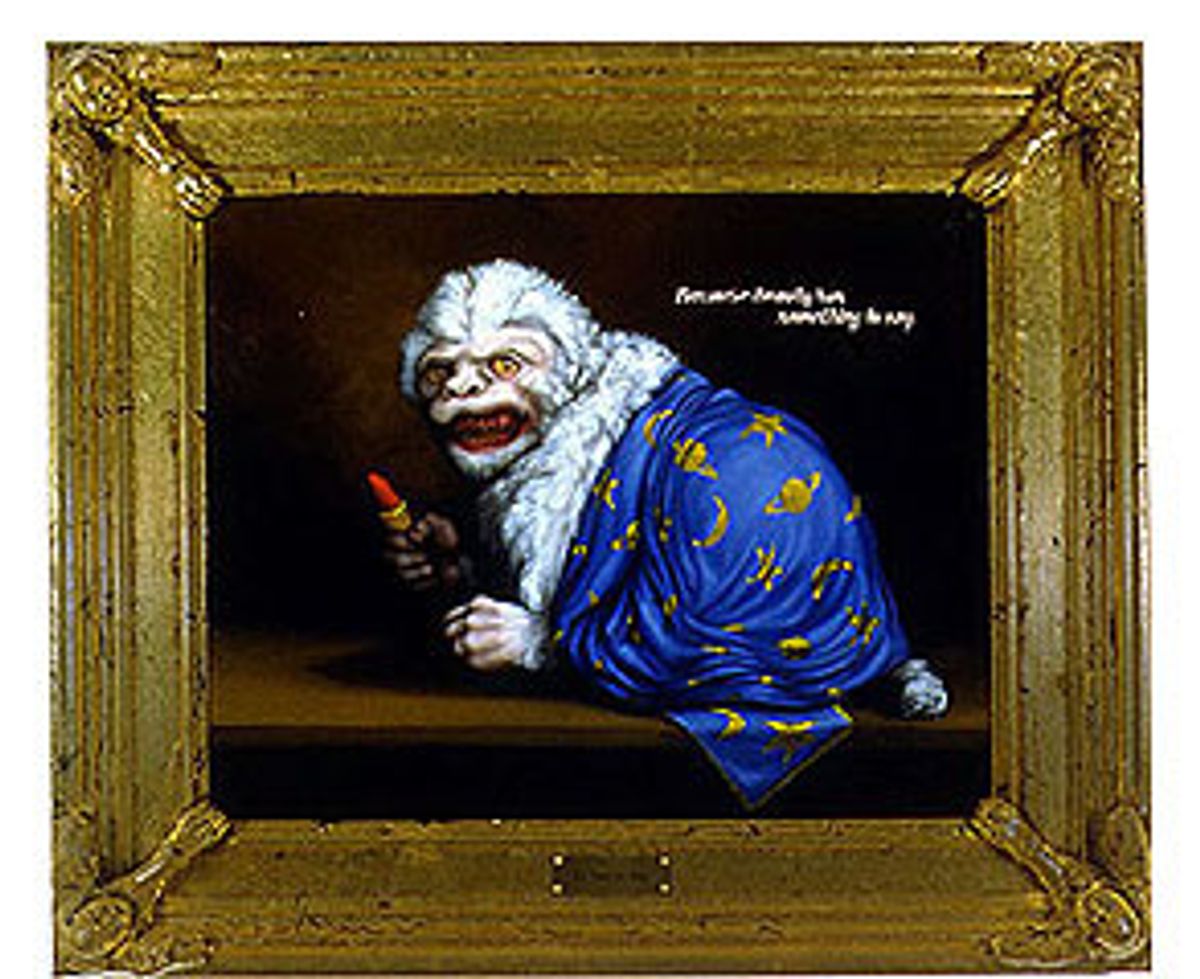

Some of Hogin's larger canvases are packed with a frenzied tangle of vividly rendered deer, dogs, rabbits, tigers, albino alligators, snakes and exotic polychrome birds, with titles such as "Allegory of the Free Market" or "The Effects of Substances in the Environment." One of the smaller works features a lone white monkey, draped in a blue and gold wizard's cape like the one Mickey Mouse wore in "Fantasia," baring its vicious teeth and holding an open lipstick, which it has smeared around its mouth, while it glares directly at the viewer. The text on the painting reads, "Because beauty has something to say."

They are mordant depictions of a natural world gone wrong -- or which has been done wrong -- where even the most benign beasts seem outraged; they're also allegorical portraits of a flourishing civilization that has become overripe and is turning toxic. "I think my most successful work is peculiar, a little bit frightening and also funny," Hogin says.

In talking about her work, Hogin refers to Schama's acclaimed book "The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age," in which he meticulously examined how the Dutch built an empire, became enormously affluent and yet lived in fear of being corrupted by their own happiness and complacency.

"There's so much they seem to have had in common with us in terms of how they viewed the rest of the world as commodities or resources for their taking, and their reveling in the commodities fetish," she says. "Also the fact that so many of their social relationships seemed to be through attainment of wealth and markers of wealth."

One of those markers -- the paintings of the period -- functioned something like advertising does today, reinforcing the values and views held by the society's leaders. At the same time, the paintings romanticized the exotic, casting the wonders of the natural world and foreign cultures as commodities to be acquired and controlled.

Those early Dutch paintings "spoke," as advertising images do now, in a distinct language, a subtle, highly persuasive visual code that can be both seductive and flattering. Today, what Hogin terms the "visual codes of corporate persuasion" are employed by advertisers, she says, to "deliver certain fantasies to consumers that are very resonant at a given time."

Advertisements for SUVs are a good example of what she's talking about, Hogin says. "When SUVs first started to become popular," she recalls, "the seductive code was about transcending an apocalyptic, chaotic landscape" that evoked images of "The Road Warrior." It's a trend still apparent in ads for some SUVs, such as the mammoth Hummer, which originated as a military vehicle. What we, the potential buyers, are supposed to come away with when viewing such an ad is that "transcendence in the context of an apocalyptic or dystopian environment becomes fun."

That advertising approach, Hogin says, "also positions the consumer as heroic, so the fantasy of having a fully coordinated, heroic, perpetually young, perpetually active body, in addition to this almost armored vehicle suggests that the two become one."

Not coincidentally, among Hogin's fascinations is the notion of cyborgs; the idea of the body becoming transcendental, mechanical and independent of nature. An associate professor of art at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Hogin teaches a graduate seminar that includes a three-week section on cyborgs. She talks about an advertisement she saw recently for a company that's working with MIT to develop new military technologies.

"This ad showed soldiers of the future who looked like 'Star Wars' storm troopers. Their humanity was completely erased, they looked like cyborgs. They were all powerful, all integrated, and I couldn't believe how seductive that was." There is something in us, she says, that finds the completely unnatural, the sterile, hypertidy and efficient very appealing.

"Everything that connects us to nature is sloppy," Hogin says, and though she doesn't agree with many of Freud's views, she grants credence to his belief that we overcome our feelings of powerlessness and lack of individuality by severing our connection with the mother's body, symbolizing nature. "Another reason," she continues, "may be the internalization over eons of the threat constituted by nature and by illness -- the development of disgust, for example."

It's a point that directly relates to one of the recurring themes running through Hogin's work: mankind's lack of empathy for, and alienation from, the natural world. As a youngster, she says, "I spent a huge amount of time drawing animals. I don't really know why, but I think it had to do with questions I had about empathy. Here was a creature whose eyes I could look into and see the evidence that it had an emotional life, perception and consciousness.

"But the only way I could empathize with that was to imagine," she continues. "And that idea became very important to me, the idea that imagination is the origin of empathy. If you really imagine what it's like for somebody, or something, you can empathize."

As an adult, Hogin says, "I've gotten my sense of ethics, and my politics -- as a citizen and as a consumer -- from imagining where I am in this network of economy and production at the global level, and imagining how I want to behave according to my effect on other people's lives." Hogin, who's married to a documentary filmmaker and has a 2-year-old son, continues, "I can imagine what it might be like to be in a place where I don't get antibiotics for my kid. Or to have been in the [WTC] towers -- what it was like for the people who had an hour to think about it."

It all comes back to the idea that empathy and imagination are linked, she says. "I suppose the eyes and bodies of animals were a huge part of that for me as a kid. Perhaps because animals are inarticulate: They won't tell you how they feel; they'll act out their feelings, but they can't express it."

Hogin clearly spends a lot of time crafting her animals' eyes, which seem by turns furious, terrified, frenzied or, at the very least, challenging, many of them gazing straight out of the painting, following the viewer just like those of Uncle Sam on the well-known "I Want You" recruiting poster.

"Animal paintings from the Dutch 17th century really grab me," she says, "because they are all about exoticism, colonialism and collecting -- the ownership of bodies. It's also about tourism, not so much literal tourism, but the psychological tourism now provided by advertising. For example, the representation of urban authenticity or drug addiction -- heroin chic -- is often couched as a form of tourism in our culture."

Hogin usually does her paintings as diptychs, triptychs or series. One of the funniest and most disturbing is her "Bunny Suites," three series of small portraits of rabbits that have apparently mutated, turning pink or acquiring the fur of some other beast, such as a tiger, the menacing teeth of a predator and, in some cases, the pose of a centerfold model. In fact, she says, they are loosely based on the "odalisques" made famous in the paintings of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, whose early 18th century pictures mythologized the sensuality and eroticism of Turkish harem slaves.

In his pursuit of the erotic, Ingres depicted female bodies that would be deformed in real life. "Those women are literally disabled. They couldn't walk if they tried to get up," Hogin says. As many have pointed out, Ingres' harem slaves would have had to have extra vertebrae to appear in real life as they do in his paintings. "Distortion in service of sexualizing the body becomes an interesting icon of sexist desires and sexist assumptions," Hogin says.

It's important to her that the paintings not be seen as geared to an elite audience. Hogin says that "the fact that the art world is so opaque has always bothered me a little bit," which is why she strives to make her work accessible. Indeed, one needn't have any deep knowledge of art to appreciate her paintings. They're extraordinary objects in their own right (she also builds most of her own elaborate frames), and the subtext of meaning is easily discerned.

"It seems to me there is a lot of work out there that just reiterates and emphasizes the class structure in this country by being intentionally opaque and inaccessible," Hogin says. "While my paintings are supported by people with money, I also find that when they get reproduced in [print] magazines or online that I get a response from a wide variety of people who really do understand them and read into the images.

"Surprisingly," she adds, " a lot of art-educated people are the ones that don't get it, and a lot of bright, interested people who don't happen to be art-educated do get it. One of the most gratifying things to me is when I hear from those people."

Despite the precision and degree of detail evident in her work, Hogin is a fast painter. Even one of her most ambitious pieces, the 8-by-10-foot "Allegory of the Free Market," done in 1999, took just three weeks to complete. It's one of her more spectacular pictures in which tiger-striped and leopard-spotted deer, some sporting excessive antlers, seem to be rearing up and bucking in hysteria while strange mutant rabbits and monkeys sit below them and a Bambiesque fawn shrieks from its perch on a hill. A banner is tied to one deer's antler. It reads "Laissez Faire."

The look of the piece, Hogin says, is loosely based on the over-the-top, heroic style of Napoleonic war painting, a formulaic approach that usually included the same essential ingredients. "There was always a hill and a yellow and black sky with roiling clouds or the smoke from battle fires," she says. "My painting cannibalizes some of that formula to talk about the romanticizing and idealization of free market theology, which was very prevalent in the '90s; people all the time talking about markets and how the invisible hand solves problems.

"These creatures in the painting, these deer, have become rampant because of free market policies," she explains. "Unregulated use of land has resulted in the destruction of predator habitat. One species becomes unbalanced, in a sense, and overruns everything." Deer overpopulation is a phenomenon that's quite real in many regions of the U.S., and in Hogin's hands works as a biting metaphor for the glorification of the free market ideology so prevalent in the 1990s.

Hogin's next exhibition opens Nov. 1 at the Koplin Gallery in Los Angeles. Her current preoccupation and the subject of the work in that show is, appropriately enough, "orientalism, the history of how we've looked east, and how we and the East have looked at each other over this significant cultural divide." Hogin explains: "We've always looked at the orient as mysterious and exotic, and as a series of commodities, but we've never understood them and they've never understood us. In the history of painting, the Middle East and the way French painters [such as Ingres] looked at the Islamic world is very interesting to me."

Hogin's a prolific, ambitious painter and a vital thinker. Her prescience in doing work that takes up greed and its catastrophic results resonates acutely now that many of the corporate elite have been exposed as narcissistic plunderers of the public trust. Her new work, which looks at the West's view of the East, the relevance of which can be seen in the news every day, promises to be just as provocative. If, as has often been said, the function of an artist in society is much the same as a canary in a coal mine, Hogin's art is worth watching closely.

Shares