Jeffrey Eugenides' new novel, "Middlesex," is a fabulous creature of sorts, like those mythical beasts made up of the parts of several other animals. It's partly the coming-of-age story of Calliope Stephanides, who at 13 learns that, chromosomally speaking, she's actually male, though due to a particular recessive gene, her body doesn't respond much to male hormones; in other words, s/he's a hermaphrodite. "Middlesex" is also the globe-spanning saga of Callie's Greek-American family, beginning with her paternal grandparents, who flee Turkish incursions into Asia Minor at the end of World War I (and who manage to escape to America and even to marry -- hiding the fact that they're brother and sister). Callie's parents assimilate and make good in midcentury Detroit, where the family weathers the racial and social tremors of the day and moves up to the posh suburb of the book's title. Then they enroll their daughter in a private girls school, where Callie meets, and falls in love with, her best friend, setting in motion the most tumultuous metamorphosis of all.

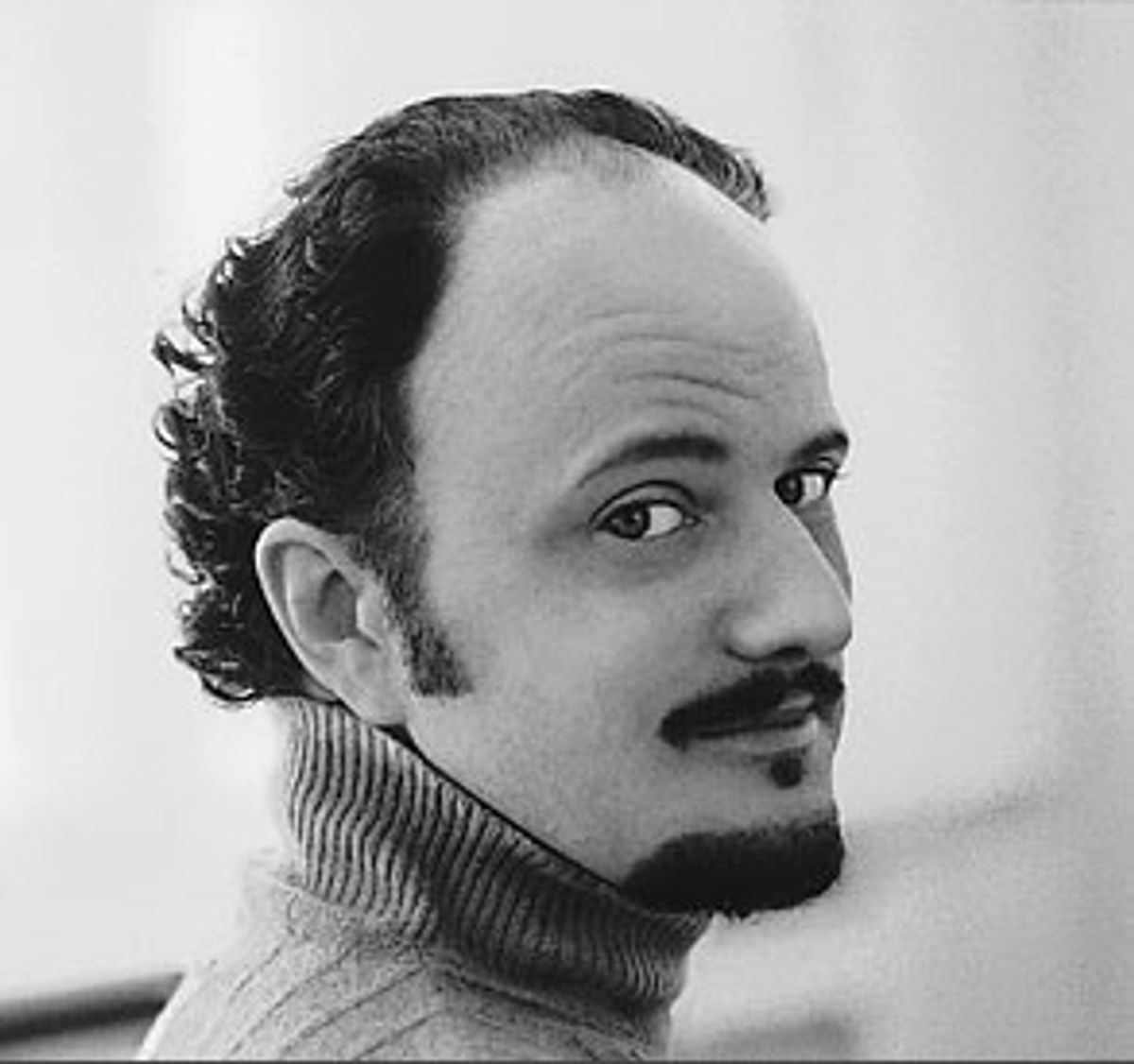

Eugenides' first novel, "The Virgin Suicides," tells the story of five sisters from the perspective of a group of boys who live in the same neighborhood. It so captivated readers (some of whom first learned of it from Sofia Coppola's 1999 film version) that "Middlesex" became one of the most eagerly awaited second novels of recent years. Eugenides recently dropped by Salon's New York offices to talk about his new book, the genetic roots of the differences between men and women, the lasting influence of Greek myths, and the weird coincidences that kept him going in the eight years it took to write "Middlesex."

Which came first, the chicken or the egg -- the novel about the hermaphrodite or the Greek family saga?

Both. The book is a hybrid, as you're describing it, and the first part came with the hermaphrodite. I read a memoir of a real hermaphrodite from the 19th century, thinking this would be a wonderful story. It had a lot of things in it that appealed to me: a medical mystery, an amazing personal transformation and a doomed passion at its center. The hermaphrodite who wrote it was a schoolgirl in a French convent, and she fell in love with her best friend. In doing that, she discovered that she was a hermaphrodite. Unfortunately, it was written in 19th century convent-school prose -- very melodramatic, evasive about the anatomical details and really unable to render the emotional situation in any regard. I was frustrated by this and thought, I'd like to write the story I'm not getting from this book.

I started to do a lot of research on hermaphroditic conditions, and the one I landed on was 5-alpha-reductase deficiency syndrome. (I always feel like a doctor when I say that.) The salient factor about it being that it only comes in isolated inbred communities. And I thought, Hmm. Isolated inbred communities? How about my grandparents being Greeks living in a small village in Asia Minor under Turkish rule? I saw how I could bring in some of my own family history in a fictional way to write this story. At that point, I realize what I had was a more epic story, a long family saga, not just about a hermaphrodite but about a genetic condition passing down through three generations of a family into the body of the girl who narrates this story of her family and what they went through as well as her own metamorphosis.

Stories about people who are sexually unusual in some way often present them as isolated. And it's true, they often have to cut off ties with their families, as Cal does for a while. But you were determined to embed her story in that of her family, it seems.

I thought of Callie's condition as symbolic of something that we all go through, which is the transformation of puberty and the process of self-discovery. I used the hermaphrodite not to tell a story that was unusual or apart from common human experience but as something that we all can relate to. To write it I drew on my memories of my own adolescence and, as they call it, locker room trauma. I thought of it, actually, as close to all of our memories and experiences.

Callie doesn't seem like a freakish character at all in this book, and that's what you were aiming for.

That's what I was aiming for. Sometimes people hear the concepts of my books -- "The Virgin Suicides": five girls committing suicide -- and they think that they are very strange and outlandish, and they get labeled bizarre or something like that. But I think when you read them, more than making reality bizarre, I tend to make bizarre things normal. I think that if you read "Middlesex," you'll see that what Calliope goes through in becoming Cal is normalized by the way I tell the story. The reason I have so much family history in this is because I wanted the character to be inside a family and inside society, to write the story of a real hermaphrodite instead of a mythical one like Tiresias.

Tiresias was someone who'd been both a man and a woman and he was questioned by the gods about which gender enjoyed sex more.

He was walking one day and saw two snakes copulating, threw his staff at them, and he was turned into a female. Then seven years later he saw the same snakes, threw the same staff at them, and was turned back into a man. The story you're recalling is an argument between Zeus and Hera over which sex has a better time in bed. Strangely, I think, Zeus thinks women have a better time and Hera thinks men do.

The grass is always greener.

I guess. So they get Tiresius and he says women have more fun, and she loses. Because she's angry at Tiresius, Hera makes him blind, but then she or another god gives him foresight, prophecy. So it's all connected with omniscience. And I certainly play with these ideas in a comic way with my narrator Calliope, who is endowed with a certain knowingness that's impossible. She's probably inventing the story of her own family to understand herself.

You don't often come across the first-person omniscient narrator. Usually the omniscient narrator is third-person, what we think of as the voice that tells classic or old-fashioned Victorian novels, this unidentified person, maybe the author, who sees everything. With the first-person narrator, you know who it is, a character in the story, but it's a limited point of view and only knows the things that he or she has seen and experienced personally. How did you decide to go with this different sort of voice?

That's what gave me such trouble and why it took me so long to write the damn book at first. It took me two years to get this first-person omniscient narrator. I was sure I needed a first-person narrator for many reasons. I wanted the story of Calliope's transformation to be intimate. I also wanted to avoid -- and this is a very practical writerly point -- to avoid the pronominal problem with he/she that we're having in this interview. I wanted it to be "I." And the point is also that we're all an I before we're a he or a she.

So it seemed important to have this "I," but in order to tell the story of the grandparents and the parents, if I remain in a first-person narrative voice, I can't go into their minds and tell you what they're feeling. It becomes very dry and voyeuristic. It took me a long time to figure out how to have a first-person that could also switch into the third-person. I had to basically give myself permission to do that, and I had a lot of scruples against doing it for the first couple of years. So I wrote the story many different ways -- sometimes all third-person, sometimes all first-person. I knocked my head until I finally realized I could have the narrator do both things and give the sense to the reader that Cal, telling the story years later, is possibly inventing things and maybe knows things that he can't but that's all right. I worried that the reader would resist certain things that Cal knows, but I've found that actually readers don't bother themselves with the details as much as I do. In general, readers don't worry about things like, how would he know this about his grandmother?

Did you know about Tiresius being a seer starting out? That almost seems too fortuitous.

I took Latin for seven years, and in 10th grade we read Ovid's "Metamorphoses" and the argument between Zeus and Hera. That was an interesting class that day -- we never usually got such information. I got to read about Tiresius early on and was interested in a figure with that kind of power and amazing experience of being both genders.

And then you had to put yourself through something like that, imagining what it's like to be a girl for the first 14 years of life. How did you go about doing that? It's very convincing. In fact, I had a harder time thinking of Cal as a man than I did in believing in Callie the girl.

Well, you can vouch for the girl part and I'll vouch for the man part! Obviously I was hoping that would be the case. I did it by following my basic belief, which is that our experiences as male and female are not so different. Any novelist has to be hermaphroditic in a certain sense, in that he or she wants to go into the minds of characters of both sexes. I took the elements of being a young boy and slid them over into a girl's experience. I mean, she's in a locker room, she's not developing, she's embarrassed about it. I was once in a locker room, developing slowly, late blooming, and remember the embarrassment of it. I would just use things that I knew and put them in a different arena.

Then when Callie decides to become Cal, she has to learn how to act like a man. Was that like being a teenage boy?

I guess. Certainly, boys try to be manly at a certain age and you ape behaviors that are masculine and I tried to remember those times. And I just imagined what it would be like now. I remember crossing my legs. You were never supposed to cross your legs at the knees. You always had to do it with your ankle resting on your thigh. I remember being very scrupulous about crossing my legs over the knee, but then I went to this new school where somehow all the men were these preppy Ivy League guys who crossed their legs like, I thought, women did. I was really shocked. I remember the different codes. Suddenly it was permissible to cross your legs at the knees, and it did feel better than putting your ankle on top of your knee.

So many people want to believe now that all those things are innate and not learned.

I don't think leg crossing is innate; I really don't. There's a certain amount of genetic determinism in our lives, but the way you check your nails to see if they're clean isn't innate, or the different ways of moving. Hips are bigger in women and so they move slightly differently, but I know women learn to walk in a certain way self-consciously, and so do men.

Did you feel in writing "Middlesex" that you were pushing against that tendency that people have now to think that everything is genetically predetermined?

Yes. Because I grew up in the unisex 1970s, when everyone was sure that gender role was just environmentally conditioned and that we could give little girls guns and they'd happily go shooting up each other. That's where I started, and now I see it completely reversed, where I'll go to the playground with my daughter and sit with a mother who has a son, she'll say, "Look at my son, beating on that rock while your daughter is playing so nicely next to that rock." And it's true that kids do seem to exhibit these innate differences, but people have decided that all of our behaviors are genetically determined and we're getting a lot of very simplistic explanations of our behavior on the basis of what hunter-gatherer societies did 20,000 years ago. I'm supposed to exhibit a lot of Neanderthal attributes and you are supposed to be out picking berries.

I'm supposed to like shopping, which I hate.

Right. That kind of thing. I find it ridiculous actually, overly reductive. And "Middlesex," while admitting a certain amount of genetic determinism, tries to open up a space for free will again in human nature. And one that I think genetics accords with. They tried to find our genes. They thought they'd find 200,000, but they found 20,000. We have as many genes as a mouse, Cal points out at one point, so why are we not mice? Something else is at work besides just genes. The old ironclad idea of Greek fate is like the idea of genetic fate we're living through now.

How important is classical Greek culture to your writing? It's ironic, given our talk about genetics, that modern Greeks are thought not to be the direct descendants of ancient Greeks, but the cultural identification is still very strong, even if it doesn't come down through the blood.

Being a modern Greek is immediately a comic situation because it's mock epic. You still believe that you've come from the ancient Greeks. There are all these arguments that the ancient Greeks were actually blond, that they were some Northern race that were inhabiting Greece. I know a little bit about things like that. Nevertheless, if you are born Greek-American, you do think that your heritage is Pericles and things like that. I remember being 8 years old and looking in the World Book and finding Alexander the Great and I said, "Dad, where's Macedonia?" and he said, "That's part of Greece." And I said, "We have him! We have Alexander the Great!"

I didn't actually start out thinking I was going to write a Greek-American novel, but because I was dealing with hermaphroditism, it brought up classicism, and classicism brought up Hellenism, and Hellenism brought up my Uncle Pete, basically. If I was going to write about Tiresius, I could write about Greek-Americans as well.

Were you raised with a lot of ethnic self-identification, or was your family assimilationist?

My immediate family was completely assimilationist. My father never went back to Greece. He didn't care very much about Greece, but there were certain times when it would bubble up in him. But in general, he was part of a generation that wanted to become American, and he did. He was a very patriotic American. He didn't marry a Greek woman or go to a Greek church. In the book, when the character of Milton sides with America over Greece during the Cyprus invasion, that was something that my father would have done. And we didn't talk about classical Greece in my household growing up at all.

Is including Greek myth in your novels a particular preoccupation of yours? "The Virgin Suicides" had some of the feeling of mythos to it.

It's not something I was conscious of at all with "The Virgin Suicides." I'm more aware of it with this book because it deals with classical themes. I think this comes less from being Greek-American than from studying Latin so much. The first books that I really read closely were "The Aeneid" and "The Metamorphoses." An epic story, and stories where people can go into the underworld and strange things like that happened, were the first stories that seized my imagination when I was young, and I'm starting to think of what a great influence those writers were on me when I look at my novels now. But I'm not conscious of trying to do that. Actually, I think that because my name is Greek, I got a lot more people saying "Eugenides has a Greek chorus" than other people would have gotten using the same narrative voice.

Did that bother you, people saying that about the first-person plural narrator of "The Virgin Suicides"?

No. It was a perfectly nice way to describe this choral narrator. But I never thought of it as a Greek chorus at all. I just thought of it as a group of boys.

You sure seem to like unconventional narrators. First you use first-person plural, then it's first-person omniscient.

I seem drawn to impossible narrative voices for some reason. I think it's related to religious literature in a way. I think with the Bible and certain religious texts, this voice sort of speaks to you. You don't know where it's coming from and yet it's mesmerizing and is full of (supposedly) wisdom and you have to listen to it. I like books where the narrative voice is in some way originless and you don't know exactly where it's coming from. That seems to me something that books can do that nothing else can do. And that is in a way the condition of literature as opposed to journalism, that kind of voice issuing from mystery.

"The Virgin Suicides" is also about a neighborhood while "Middlesex" is about Detroit. Is that something you intended for this novel all along?

Once I knew I was going to write a book that dealt with history, I wanted to bring Detroit into it. I do have a perverse love for my hometown, and I think Detroit as a setting is really rich material. It's this great industrial city that has decayed. It produced Motown, Madonna and now Eminem, but it's also been destroyed by racism. All these things that are in Detroit seem central to the American experience to me. I've never found a reason to write about another place because everything I was interested in writing about was already there where I was born even though I left many years ago.

I wanted to bring in as much Detroit history as I could, and as I started to read more about Detroit, things just seemed to apply to this story. I found out that the Nation of Islam was founded in 1932, exactly the year I was writing about, in Detroit. And the Nation of Islam was founded by a man who was supposedly a mulatto and he worked in the silk trade and no one knew exactly where he came from and he had all these theories about racial origins and genetic transformation, and this was exactly what "Middlesex" was about. My grandparents and the grandparents in the novel were silk farmers. It all seemed connected.

There's also the strange coincidence that a Mr. Eugenides is described in T.S. Eliot's "The Wasteland" as "the merchant from Smyrna." What about the burning of Smyrna? Were your grandparents really there?

No, and I hasten to add that they also were not brother and sister. Greek-Americans are obsessed with the burning of Smyrna [by the Turks in 1922]. Once Smyrna came in, I knew I had to work in Mr. Eugenides. My Latin teacher was the first person to point out to me that I had the same name as someone in T.S. Eliot, and that seemed like a calling to become a writer.

It seemed like the construction of this book involved an unusual number of coincidences.

I had some incredible coincidences in writing this book. My wife had to go see an endocrinologist on the Upper West Side. We went up there, and I started asking him questions about genetics because I'd been reading all this genetics and sexology material. He said, "Are you a physician?" And I said, "No, but I'm writing this novel about a hermaphroditic condition," and I start to explain to him what it is when he swivels around and takes out this old yellowed journal, and it turns out that he was one of the original researchers of the article that I was basing my novel on.

That's weird.

It was. Want to hear another one? I was writing about River Rouge plant, the Ford plant, and I happened to call a friend in Michigan who lives nowhere near the plant, and a woman answered and said, "Hello? We just had an explosion!" It turned out that my phone call had somehow been re-routed to the River Rouge plant, which had a big explosion on that day.

The last one I'll tell you about is that I was trying to describe the grandparents in the book, and so I was trying to remember this old photo of my grandparents that my parents had in the basement. I hadn't seen it in 10 years, and so I was struggling to remember it, and just as I was writing that description, the doorbell rang and it was the FedEx man who was delivering that same picture from my parents' basement that had been there for years. My mother, without telling me, had gotten it framed and sent it to me, and she didn't know I was writing about them or anything. That was very strange.

Did that ever spook you?

When you're writing a book that takes as long as this one did, that's the sort of thing you need.

Shares