With a strong congressional war resolution in his pocket, President Bush now must convince a handful of world powers on the United Nations Security Council to sign off on his campaign against Iraq's Saddam Hussein. By all accounts, it remains a tough sell. The days leading up to the council's vote will feature lofty debate and pointed questions about U.S. intentions, but the actual deal may be cut behind the scenes, where foreign policy matters far less than nationalism, brinksmanship and greed.

Billions of dollars in old debts and billions of gallons of untapped Iraqi oil seem to be critical to the stalemate. Russia and France are anxious to make sure that their long-established energy interests in Baghdad are respected in a post-Saddam world, and that U.S. and British companies are not given economic preference in the region. While both countries seem to be generally concerned about America's military plans, experts say those concerns could be greatly allayed in the form of upfront White House concessions.

"First and foremost this is about money, not principle," says Russian specialist Michael McFaul, senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment. "Russian President [Vladimir] Putin and his administration believe the United States will go ahead with or without them so they're trying -- and not very successfully for now -- to extract what they can from America."

Negotiations remain fluid and a deal could be struck at any moment. But why is the dance so important? After all, administration hawks dismiss the need for U.N. cooperation, insisting America will fight Iraq with or without official international backing. But for the Bush administration, there's a catch: Most public opinion polls show that a clear majority of Americans want an international blessing before bombs start falling on Baghdad. If the White House doesn't win U.N. support, it could pay a high price domestically for acting without it.

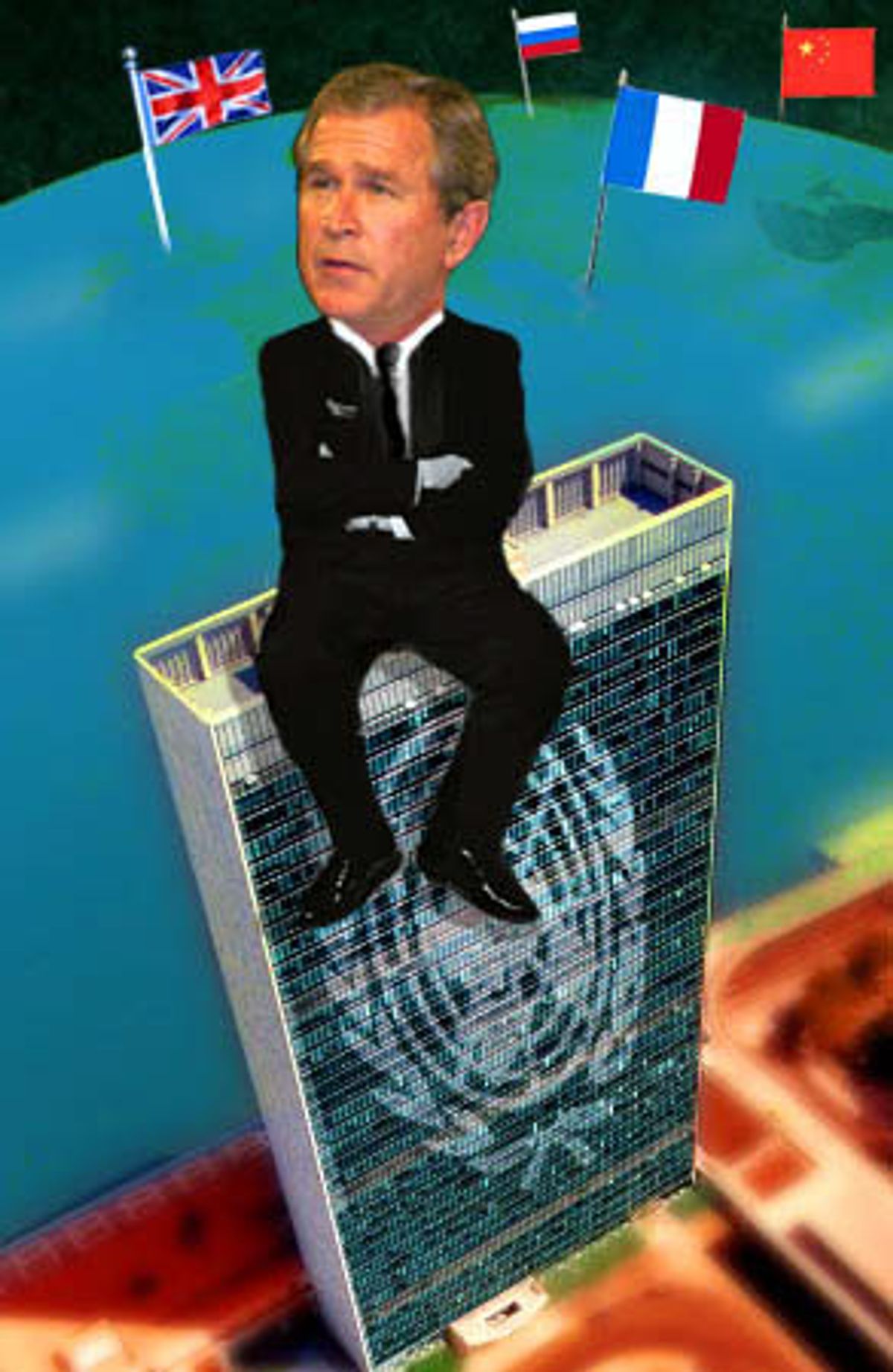

The Security Council will have a final say in authorizing any internationally sponsored military action in Iraq; having won in Congress, the White House will now turn its lobbying to the council's four other permanent members: Britain, China, France, and Russia.

The single, strong resolution Bush wants would not only send U.N. weapons inspectors back into Iraq, but would give the U.S. authorization to use military force in the event of a "material breach" of the U.N. inspection resolution. The breach would be defined by Washington.

Britain and Prime Minister Tony Blair have strongly backed the U.S. But France, Russia and to a lesser degree China remain obstacles in the United States' way, with France standing out as the least predictable of dissenters. All three have expressed opposition and want chief U.N. arms inspector Hans Blix and his team to return to Iraq immediately to begin their work. The U.S. wants the team to wait until a new, tougher U.N. resolution has been passed.

Negotiations on the resolution have intensified in recent days, with some sources saying that the U.S. is already making headway. But experts remain split over how the final document may look. "Eventually, the final resolution will be tilted substantially in America's direction," says U.N. expert Kenneth Rodman, professor of government at Colby College in Maine.

"I don't think we'll see from the U.N. the kind of resolution Bush wants," counters Jean-Robert Leguey-Feilleux, professor of diplomacy and international law at St. Louis University.

Despite a month of intense back-and-forth negotiations, spearheaded by Secretary of State Colin Powell, no breakthrough has been reached.

For now, China, France and Russia refuse to sign off on the resolution being pushed behind the scenes by the White House. The three countries, concerned about writing the U.S. a blank check, prefer a two-step approach: One resolution would set out tough conditions for Iraqi cooperation with weapons inspectors and, if necessary, a second Security Council resolution would authorize the use of force if those conditions are not met. Bush has opposed a two-resolution process, fearing that it would limit his ability to retaliate quickly if Saddam restricts the inspectors.

"From their perspective, the U.N. is really the last line of defense from a world in which the United States does whatever it wants, wherever it wants," says Paul Saunders, director of the Nixon Center, a nonpartisan foreign-policy think tank based in Washington. "That kind of world is very frightening to them."

The Russians, Saunders says, have no real affinity for Hussein. In fact, a recently published poll there shows just 4 percent of Russians think the country should back Iraq in a war with America. "But," he explains, "they want to see their interests protected, which is how they would put it."

Specifically, Russia wants to protect the 30-year-old, $8 billion debt Iraq owes for military equipment purchased in the Soviet era. Moscow also wants to protect multibillion-dollar Iraqi oil-drilling contracts recently signed by Russian energy companies. The forward-looking contracts, valued on paper at $40 billion, were approved with the hope of opening up Iraq's vast oil reserves once U.N. sanctions were lifted. Those sanctions have made it illegal for oil companies to do business with Iraq.

"The oil is the main thing," says Saunders. "There is widespread nervousness in Russia that if the U.S changes regimes in Iraq, then all the oil contracts will come to the United States and Russia will be left out. That could be a real problem for Putin. He has to demonstrate that Russia is getting something out of it [a vote in support of Bush], other than good will."

In other words, "nobody in Russia wants to be answering the question, 'Who lost Iraq?'" says George Lopez, director of policy studies at the Krock Institute for Peace at the University of Notre Dame.

An oil exporter, Russia is concerned that if America's regime-change action in Iraq is pulled off flawlessly, that could translate into lower oil prices over the long term. "That would torpedo Russia's economy," notes McFaul. He also thinks the oil contracts are a non-starter with the Bush administration, and that Russia should focus its energy on getting Iraq -- or someone -- to repay the debt.

Putin has staked his entire foreign policy on trying to move Russia, diplomatically, into the community of Western nations. "This is precisely when you say whether you're in or you're out," says McFaul. "I'd be surprised if Russia votes no."

Of the three permanent members of the Security Council in play, China appears to pose the least threat to the U.S. policy. Although it has voiced reservations about the proposed U.S. resolution, experts doubt China would torpedo any proposal. "Under their broader strategic thinking, China's best interest is to have good relations with America and to keep quiet about the U.N. resolution," says Cheng Li, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and professor of political science at Hamilton College in upstate New York. For political consideration though, he thinks China would abstain, rather than vote in favor of a U.S.-sponsored resolution. "Being pro-United States looks silly at home," Li explains.

Ideally, foreign policy analysts say, the U.S. would like to peel Russia away from the dissenters in hopes that France would not want to cast the lone veto. Conversely, if France gives in to the U.S., either by voting yes or agreeing to abstain, it's unlikely that Russia, with too much to lose from fractured relations with the U.S., would stand in America's way at the U.N.

"It's clear Moscow is not prepared to let this issue stand in the way of the rest of U.S.-Russia relations," says Saunders.

As for the possibility of France casting a lone veto, "it's touch and go," says Lopez at the Krock Institute for Peace, which has been in regular contact with French diplomats. "At this point I'd say yes [to a French veto], but next week it might be no."

That's why, at least temporarily, France has emerged as the most important diplomatic player in the pending war with Iraq. In late August, French diplomats signaled that they were willing to work with the U.S., perhaps even to provide troops as they did during the Gulf War. But things cooled in September when the U.S. rejected Saddam's initial offer to allow inspectors back in the country. Then came France's suggestion of a two-step resolution, followed more recently by dismissive comments from the French prime minister, Jean-Pierre Raffarin, eschewing a "simplistic vision of the war of good against evil." The jab seemed clearly directed at the White House.

In recent weeks, France has become a sharp thorn in the side of the administration. "It's a position the French like to be in," notes Craig Parsons, director of the European Center at Syracuse University's Maxwell School of Public Affairs. "They have been making sure they take distinctive positions from the United States all through the postwar period."

Yet there are reasons why France's stance at the U.N. is not being dismissed out of hand as Gallic pride or quixotic obstructionism. For instance, despite often clashing with the U.S., French leaders recently backed U.S. military action in Afghanistan, Bosnia and Kosovo, which shows they are not allergic to all U.S. use of force. Also, led by newly elected President Jacques Chirac, France today is governed by moderate-to-conservative politicians, not left-wingers with a knee-jerk opposition to America's foreign policies.

"What could induce France to back America's campaign? I don't see it," says Leguey-Feilleux. "The concern for France is that the consequences of this war would be drastic. Then she could say: 'Look, listen to us next time.'"

Adding backbone to France's resolve is the fact that its position is immensely popular among French voters. Also, minus Britain, most of the European community stands behind France at the U.N., an uncommon occurrence. Especially comforting is the fact that Germany, in a rare move, has out-flanked France in its opposition to America's policy, thanks to the strident antiwar rhetoric from Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder during his successful reelection campaign.

Meanwhile, experts say, France would not pay that big of a political penalty for challenging the White House at the U.N., in part because it's not as dependent on the U.S. as Russia is. "There's not that much of a downside, given that current French leadership is already lukewarm to the United States' transatlantic agenda," says Parsons.

But can France openly oppose a war and still protect its significant economic interest in a post-Saddam Iraq? France is Iraq's biggest trade and investment partner in the West, with French commercial interests in Iraq now worth $4 billion. And Iraq reportedly owes France $4.5 billion.

They can be protected, Parsons says, thanks to France's historical ties with Iraq. Also, France could gain economic entry when America inevitably calls on its European allies to help rebuild the nation after the war. "I think French will have a reentry strategy no matter what happens," he says.

No doubt as negotiations intensify this week at the U.N., that reentry strategy will be a topic of much private debate.

Shares