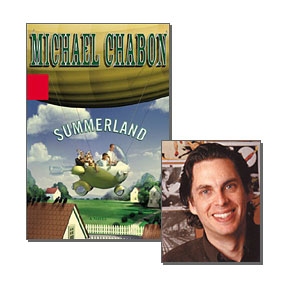

Michael Chabon’s new novel, “Summerland,” is meant for kids, but it’s just as rangy, eccentric, dreamy and funky as his books for adults. Chabon, an avid reader in his own childhood of classic children’s fantasy series by such authors as Susan Cooper and C.S. Lewis, decided he wanted to try his hand at the genre and bring to it a set of American mythic motifs. “Summerland” takes baseball as its theme, a game full of heroism, but one also redolent of nostalgia and the sting of inevitable failure. The novel’s hero, Ethan Feld, is a reluctant player trying to please his baseball-smitten widower dad on a small island off the coast of Washington state. When he’s enlisted by a supernatural scout to help rescue this world and the magical world called the Summerlands from the schemes of the trickster god Coyote, Ethan has to step up to the plate in more ways than one. He gathers the necessary entourage of friends and sidekicks and sets off on an epic journey across the Summerlands, encountering thunderbirds, giants, ferishers (a roughneck breed of fairies), Sasquatch and a half-dozen tall-tale folk heroes along the way.

Chabon kicked off his literary career with the dazzling “The Mysteries of Pittsburgh” (1988), helped adapt his 1995 novel “Wonder Boys” into an acclaimed film in 2000 and won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for fiction for “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay.” He had been intending to write a book like “Summerland” for almost 30 years, but the many new fans the novel is sure to earn him won’t have to wait quite so long for the sequels. He recently signed a contract to write two of them. Chabon dropped by the Salon offices recently to talk with us about the creation of the Summerlands, his passion for baseball and the vanishing adventure of American childhood.

I was a little surprised by how much I enjoyed this book because when I started it I wasn’t sure about the baseball angle. You’re nodding your head as if you’ve heard that before.

Yes, I’m used to it. In a way it was similar to what happened with “Kavalier and Clay.” When people heard that was about comic books, I got a lot of “Oh, really? ‘Cause I thought I might be interested until I heard that.” I was aware there was going to be some initial resistance from some people.

I know you wanted to write a children’s fantasy novel that was grounded in America in the way classic British children’s fantasy is grounded in the land and mythology of that area. Tell me how you got to the baseball theme and some of the other elements of the novel.

I had the idea to do the fantasy part of it first. That had been with me for some time, since I was a kid. When I was 10 and 11 years old and deciding I wanted to be a writer when I grew up, the kind of books I wanted to write were something like Susan Cooper’s “The Dark Is Rising” sequence. That inspired me to want to write, and to write books like that. I wanted then to do with American mythology and folklore what she does in those books with Arthurian and Celtic mythology, but I went on to other things and never wrote it.

Then when I had kids of my own and started reading to them aloud at night I rediscovered a lot of those books that I loved so much, and started thinking again about writing fantasy for children. And I had this other idea of writing something about baseball because I could never find a book about baseball for kids that communicated what I thought was important about baseball and what I love about it. Most kids books that aren’t just out and out sports books — like “Batter Up!” or that sort of thing — use baseball as a backdrop or as window dressing for the story, but they didn’t get at baseball. I had these two ideas, and as soon as I started thinking about the fantasy and using American mythology it just seemed to me that baseball was part of that and was a natural fit. Somehow the novel was going to work in this world that was an American mythological universe and also a baseball universe.

Was it hard to put those two things together?

No, it just happened. It came very easy. In fact, baseball has an origin myth, like the city of London. There’s a myth of this guy, Abner Doubleday, who became a Civil War general, drawing lines in the dirt in Cooperstown, N.Y., and telling his friends where to stand. That’s just complete fabrication. There’s a mythic quality — which is something people have often said about baseball, but I think it’s really true. You have things like Cool Papa Bell, the great Negro Leagues player who they said was so fast that he could get in bed under the covers after turning off the light but before the light actually went out. That’s like something they’d say about Hermes. It just felt natural.

When you decided to base the book on an American mythology, what kinds of elements did you gather together? Did you already have in mind everything that you wanted to include?

It just grew. I’ve always loved the tall tales, the stories of Paul Bunyan and Pecos Bill and Old Stormalong and John Henry. As a kid, I started with “D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths,” then I read their “Norse Gods and Giants” and then it seems like the next book I read was a huge book whose title I can’t remember, a treasury of American folklore. Those stories all completely blurred and blended in my mind. I didn’t really distinguish among them, and I have to say comic book superheroes were in there, too. When I was maybe 7 years old, there wasn’t too much difference for me between Superman, Paul Bunyan and Hercules. It was all part of the same thing. That putting together of popular stuff and classical stuff and American stuff, that’s how this book came to me. It wasn’t an artificial thing.

I think the only stuff that I deliberately introduced was the figure of La Llorona, the Southwestern figure [a ghostlike mother spirit who can be heard wailing for her lost children]. She wasn’t something I knew about as a kid. I just started reading about her about 10 years ago. All the other elements, as disparate as they seem, really come from the same place in my memory or my history as a reader, but she’s a recent addition. She worked her way into the story because she had to do with Ethan’s dead mother and his mourning for her. The rest of it just emerged from Ethan Feld, who is not that different from how I was at 11.

Except that he’s not interested in baseball.

No, not at all.

And were you?

I was a big baseball fan, but I was no more skilled on the field than he is. In fact, I was probably worse. The narrator says of Ethan that he was not a terrible klutz, and I was. I loved baseball. My father is a baseball fan. He grew up a Brooklyn Dodgers fan. There was an early taste of disappointment in my exposure to baseball. You’d think that would have discouraged me, but for some reason it didn’t. The first team I loved was the Washington Senators (I grew up in the D.C. suburbs), and they were taken and sent to Texas. They became the Texas Rangers when I was about 9 or 10. That just broke my heart. Then I transferred my love and affection to the Pittsburgh Pirates, particularly Roberto Clemente, their great player, and two years after that he was killed in a plane crash.

It’s a tragic thing.

It is. It’s always had this tragic element that’s carried me through a lot of crass, ridiculous, callous behavior on the part of owners and players over the years. There’s some essential sadness in the game for me.

Why did you make Ethan someone who doesn’t like baseball? Was he a stand-in for all the readers like me, who at first thought, Oh, great. Why don’t you just write a fantasy novel about bridge?

Yes. [Laughs] Hey, why didn’t I think of that? Well, there’s always a sequel. It was a way of handling what I expected would be a certain amount of reader resistance. I have this sense that kids today aren’t into baseball at all in the way they used to be, just as they’re not into comic books the way they used to be. Since this book was going to be for children, I thought, statistically speaking, that probably most of the kids who would read it might not really be into baseball. I thought that if I had a character who was a huge baseball fan that would be too hard to identify with. So I decided I’d have him not like baseball.

The instant I made that decision, all this other stuff clicked into place. His father would have to be a huge baseball fan, and he’s disappointing his father and that’s why he keeps doing it because his father wants him to.

But then I do have [Ethan’s friend] Jennifer T. Rideout, who is a huge baseball fan, and that gave me the opportunity to approach the game from a kid’s point of view that was also very sympathetic to baseball.

Do either of your own kids like baseball?

Well, my daughter is almost 8 and I think 8 is the age when a kid really starts to like baseball. Because it’s hard to understand: It’s illogical, it’s complicated. There’s math involved. So 8 is the age and so far it doesn’t look like she’s heading toward baseball. My son is 5. I have hopes for him.

But my daughter played an important role in this book because she is extremely prejudiced against fiction that doesn’t have strong female characters. She hates books where the girl is just being rescued over and over again. She won’t let me read them to her and she won’t read them herself.

What books are like that anymore?

Well, you’d be surprised. Lloyd Alexander’s books. I loved them and brought them to her, but she always had a hard time with the figure of Eilonwy. She always speaks her mind and that’s good, but that’s about it. Other than that, she’s always in trouble, always needing to be rescued.

So with Jennifer T. Rideout I really tried to create a character that would get past her.

And what does she think?

She thought it was all right. I had this wonderful moment when I was reading to her and there was a sentence in there, which I should be able to quote verbatim, but it’s something like, “A baseball game is nothing but a great contraption to get you to pay attention to the cadence of a summer afternoon.” I read that sentence and paused before going on to the next paragraph and in that little gap she said, “Nice.”

I don’t think that at 8 I would have known what the word “cadence” meant. But kids are not as put off by things they don’t understand as adults are.

They leap over it. Or else they ask. It used to be a real pleasure for me to ask my parents what a word meant, because they usually knew and I liked that, that they would know the answer.

Did you worry about some aspects of the book being hard to understand? Did you write in a different way?

I tried to be conscious of vocabulary and to keep it more simple, relatively.

You’ve always chosen from a broad palette of words.

Yes, so I did narrow it, but not that much. I was aware sometimes of choosing a word that might not be superfamiliar, like “cadence,” but I just went with it. It wouldn’t have bothered me when I was 11, so I’m just trusting that it’ll be OK.

Along the same lines, there are more references to sex and …

Bodily functions?

Yes, and body parts, like the breasts of the Bigfoot character. Several characters notice them and are aware of them without dwelling on them. “Summerland” is a lot earthier than many children’s novels. Was that a deliberate choice?

I just felt that that’s how I write. I thought, if I’m an 11-year-old kid and I’m confronted with this big 9-foot female Sasquatch, I’m going to notice her big black breasts. I’m just going to notice them. I noticed them on pictures of gorillas when I was that age and I notice them now. Everybody notices them, so what’s the point of not talking about them? And I was thinking that if I wasn’t allow to do that, someone would tell me but nobody said anything.

There’s also alcoholism, a dead mother and a mother who runs away — elements that you think of as turning up more in nonfantasy fiction for kids, the kind of book that deals with issues. But this doesn’t feel like “issue fiction.”

You mean the kind of book where they say, “Now here’s the lesson about shoplifting”? Exactly. As a kid I loved fantasy, even out and out fantasy with no ties to the world around us at all, but I also liked realistic fiction like “Harriet the Spy” or “From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.” And what I really liked was stuff like Susan Cooper, where she does both at once. She has these very contemporary (for the time) British children having these adventures in this world of Celtic and Arthurian romance.

Did you run into any particularly big challenges in pulling this thing off?

What was hardest for me was that I had so many characters. I needed to get the number of characters up to where they could have a baseball team, nine players. It was a lot. I struggled with that, to make sure that I introduced the characters in good time, that I kept the pace going and also that when they did get introduced they’d be unique and interesting even though they couldn’t all be main characters. I still wanted them to feel vivid and alive. That was the hardest. But it wrote itself pretty quickly. This was the most fun, easiest writing that I’ve had in a long time.

Why do you think that is?

Partly because it had been sitting around inside me for so long waiting to be written. When I started letting it out, it just came out and it was ready. Also maybe because I was working on the screenplay for “Kavalier and Clay” at the same time and that was very hard, often tedious, repetitive, going over the same material, the same characters I’d been living with for four and a half, five years at that point. I’d finish a draft of that, which was always labor, and then turn to “Summerland” and it just felt so liberating. There was a sense of liberation that came from writing fantasy, too, I have to say. It was really hard to write the novel “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay” because there are plenty of people around who were there and remember what New York was like in 1940 or ’44. I had to measure up to those people’s knowledge.

And that’s the kind of body of knowledge that some people are totally fanatical about. They’ll be all over your case if you say that the cellophane on the toothpicks at a particular deli was red when it was actually green.

Exactly, and I sweated that stuff a lot. With “Summerland” I got to make it up. People have asked me, “Isn’t that hard when you have to make everything up?” and I say, “No, that’s easy. Making stuff up is easy. Getting it right is hard.”

One thing I loved about “Kavalier and Clay” was the way the characters created heroes for their comic books whose superpowers compensated for the ways they felt inadequate in their own lives — the Escape Artist was invented by a man who couldn’t get his family out of Nazi Germany. Was there anything in “Summerland” that served that purpose for you?

There’s this appeal in stories with the idea of people being chosen. Especially in the Susan Cooper book “The Dark Is Rising” — which I think is the best of the sequence. It’s all about how this kid Will is really one of the Old Ones, even though he’s never known it until this moment.

Or Harry Potter.

Yeah, Harry Potter’s another one. The idea that you’re the special one, even though that seems so unlikely and you’ve never known it. That has a very strong appeal for a certain kind of kid, and maybe since Harry Potter has been so successful, for a lot of kids. That old fantasy of mine is definitely part of what’s going on in “Summerland,” with the idea that Ethan Feld is a secret champion even though everyone, even the person who’s scouted him to be a champion, is somewhat skeptical about it.

You have him go through this whole process with it where it doesn’t just happen. First he hears about it, then he thinks he’s failed at it, then he has to make it happen. He has an almost postmodern relation to the idea. It’s not an unexamined theme for him.

I guess it wouldn’t be that way. I have a lot of respect for what J.K. Rowling’s done in her books. They’re very pleasurable and enjoyable, but if I had a criticism of them it would be that Harry is too good and too talented too quickly and seems to take to the idea that he’s the special one too easily. It’s always about Harry winning. That’s what he does again and again, and if he ever gets into trouble it’s not because he’s weak or ineffectual and not up to the task, it’s because his opponents are so evil, or someone betrays him so he doesn’t stand a chance. I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t imagine that character because it’s not enough my own experience of childhood.

Especially if you’re writing a book about baseball, a game where there’s so much failure involved as a matter of course.

Right. Baseball is a game of failure. It just all fit. Ethan made the baseball work. For example, at the very beginning, when he’s railing that the fact that they keep track of errors in baseball seems so unjust to him. And yet I felt that was perfectly appropriate for Ethan Feld that this would be the sport that he would become involved with.

How about the missing mother theme, which is so prominent in this book and so many kids books? There’s Harry Potter, and Nancy Drew.

That’s why that Kelly Link story is so wonderful. I guess I felt it was part of the tradition, but people have pointed out to me that it’s been part of almost every one of my books. Joe Kavalier leaves his parents behind and they’re gone, and Grady Tripp in “Wonder Boys” is an orphan from childhood, and Art Bechstein in “Mysteries of Pittsburg” — his mother is dead. It might be that I was so deeply steeped in children’s literature and the whole idea of the absent parent that that was just inevitable. But what I really think is going on is that it’s just one less character to have to write.

That’s terrible! The structuralist explanation: It’s all about the lazy novelist.

But also, you know, a character works best when that character has a wound that needs to be healed, and one of the deepest, longest-lasting wounds that a person can have is to have lost a parent. I didn’t lose either of my parents, thank God. They’re both still living. But I guess because they were divorced when I was young — that’s a lesser wound but it’s given me access to imagining the greater wound.

Also, a child without a mother is not as closely supervised and is more on his or her own. It’s being forced to grow up too soon. And that’s another persistent theme of yours: youth, or boyhood — literally or figuratively …

Overgrown boys.

Yes. Even in “Kavalier and Clay,” one of them gets married, but the thing that they create, their art form, is for boys.

The idea of boys and boyhood is very strong in “Summerland,” too. There’s this bit about this defunct quasi-Boy Scout organization called the Braves of the Wa-He-Ta. There’s this official tribe handbook that Jennifer T. is given, and it comes in handy.

It’s so useful! I love that. It’s this hokey scouting handbook, but somehow just when you need it, it’ll tell you something like how to pick a lock.

Even though it was written by a guy named Irving Posner in Pittsburgh in 1926 or whatever.

What I came to see I was writing about, which is something that’s of great concern to me as a parent, is what I see as the lost adventure of childhood. I remember a childhood that was the kind of childhood that people had been having in the United States going back at least four or five generations before me. It was rooted in independence and freedom. I’d just go out in the morning on Saturday morning and say “Bye, Mom” and I’d be gone all day long.

She wouldn’t know where you were.

She would not have the faintest idea where I was, and I’d come home for dinner. And I’d get into a lot of trouble, no doubt about it, and probably almost died a couple of times, but still that’s the world. It dovetailed so completely with what I read, so when I went out to play I could go play in Narnia or I could go play in the Virginia wilderness of George Washington’s boyhood if I was reading a biography of George Washington. There was a seamlessness between the world of literature and fantasy and the world that I was living and playing in. That really mirrored what was going on in the fantasy worlds themselves, where there was a seamlessness and a porousness between, say, England and Narnia.

Or even something like Tom Sawyer. Even though I wasn’t a boy, there was a Tom Sawyer element to my childhood. Our mother didn’t know where we were half the time and there was so much more undeveloped land to play on.

There was more undeveloped land and so much more free space. And now so much of the space we put our children into is created by adults for children. It’s licensed by adults, patrolled and permitted by adults. There’s nowhere for them to disappear into. They’re under surveillance all the time. It’s that idea of that lost … that’s the Summerlands, to me, ultimately. That this is imperiled, or probably gone forever, is a very painful idea to me. Maybe that ties into the idea of a lost innocence or a lost boyhood.

In a way it’s not a lost innocence, though, because now children live in this artificially maintained innocence, the place where everything is safe.

It’s lost experience, I guess. On the other hand there’s all this pressure on them to grow up too quickly. A lot of homework. You don’t get to be a kid in the way that you once were automatically granted the right to be a kid. It’s a painful thing.

Why did you set “Summerland” in the Pacific Northwest?

I lived on an island there and for one year I was the scorekeeper for a Little League baseball team. I had never played Little League baseball, since my father wisely sought to protect me from my own failings. He didn’t even let me get near a bat, basically, because he was afraid of the consequences. So that was my exposure to the world of Little League. I got to see it both from the bench, ’cause I would sit on the bench with the kids, and also from the adult, parental point of view. I got to see what the parents were like. I got to see how the more talented kids treated the less talented kids. So when I was writing this it just seemed inevitable that I’d set it there on an island.

The Pacific Northwest is also a place where a sense of wildness still persists.

And the kids are allowed more freedom, as I think is still true for kids in rural settings. They’re granted more freedom than kids in urban or suburban settings. It’s true, I needed that. If I’d tried to set this in Berkeley, Calif. [where Chabon lives] it would have been a lot harder. Jennifer T. and Ethan would have been scheduling play dates with each other. It gave me the liberty to create the same kind of adventure that I grew up reading, which felt so much a part of my own experience then but I fear that for a lot of kids might feel somewhat remote.

You’re also writing screenplays, which is something that I think of as a job that novelists take on when they need to make some money. But you seem to be doing it out of choice.

Well, not entirely. I insure my family’s health through the Screenwriter’s Guild and you have to make a minimum amount every year as a screenwriter to keep your insurance up. I mostly do it for the insurance, actually. But this most recent one — I just got offered the chance to do “Spiderman II,” or to take a whack at it, I should say. I could have passed it up because I just finished the “Kavalier and Clay” screenplay, but I just couldn’t resist.

So you really wanted to do it?

It was just too good of an offer. I love Spider-Man. I grew up loving Spider-Man. I love Peter Parker, he’s a great character. Of all the things in that first film, what I liked best was the Peter Parker stuff. I thought Tobey Maguire was great, and the parts that had to do with this ordinary guy having to come to terms with having these amazing abilities. And even the freakishness about it. There were only hints of that in the first film but there was a freakish, almost Peter Lorre aspect to it, where those things are growing out of his skin. So how could I say no?