In remaking the beloved 1963 Parisian caper flick "Charade," Jonathan Demme has tried to infuse his version with the music and cinematic style of the 2000s and the spirit of the French new wave. So at the very least "The Truth About Charlie" is fun to watch in a chaotic, everything-but-the-kitchen-sink way. We careen through the streets of Paris while rai and Afro-pop blast on the soundtrack; we keep running into enigmatic women from the glory days of Euro cinema (actress Magali Noël and director Agnès Varda appear in cameos, and one-time Godard leading lady Anna Karina presides over a hilarious tango sequence); we see repeated shots from the POV of a corpse on a slab in the morgue.

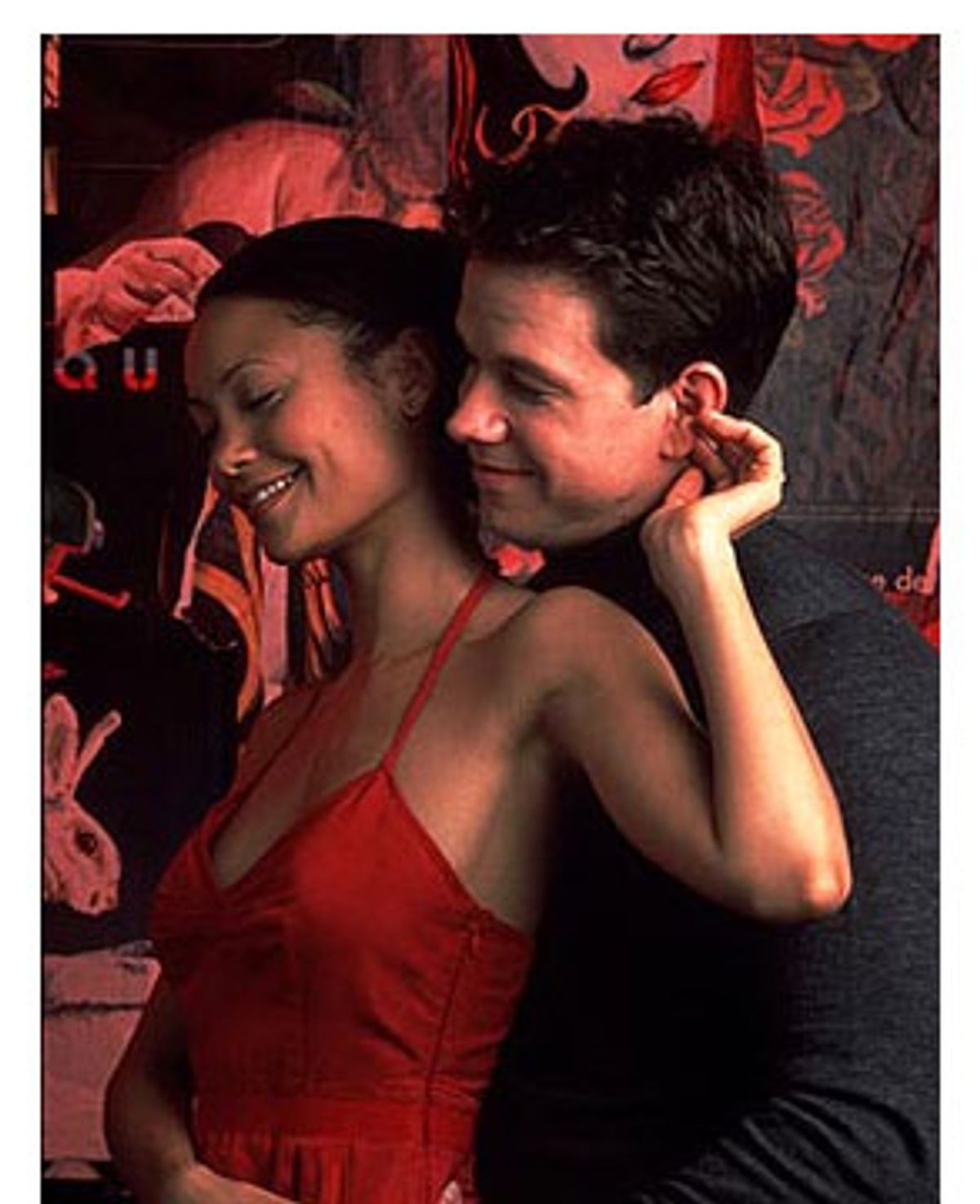

Demme's casting is also highly entertaining, although I wouldn't go so far as to call it successful. This movie's resemblance to its predecessor is pretty vague, but Thandie Newton actually does a better Audrey Hepburn impression than I could have imagined, pixie-ing and moxie-ing her way through the incomprehensible plot in that half-apologetic, half-sardonic fashion. I'm not saying Newton has anywhere near Miss Audrey's inimitable screen charisma, but she's got the button nose and the wasp waist; she can't weigh much more than a wet raincoat. (She's also got the right girls'-education mannerisms. When told that her late husband was an international bad guy with a zillion identities, she responds, "Perhaps I will have that ciggie.")

As for Mark Wahlberg playing her on-and-off love interest, there's not a lot to say, and the less you think about Cary Grant playing that role in the original "Charade," the better. Wahlberg's French is passable, and his sequence of hats hilarious. The preview audience with which I watched the movie was on the floor over that über-Froggy beret he wears in one scene, and later there's a fedora that makes him look like the kid who got drafted for a small role in a suburban high school production of "Guys and Dolls."

I'm risking film-critic heresy here, but I can't be the only person who thinks "Charade" is kind of a snooze. Sure, Grant and Hepburn are always easy on the eye and their outfits are great, but the story is limp and unsuspenseful Hitchcock lite, the dialogue is loaded with that not very risqué '60s repartee, and the whole movie basically slides downhill from the awesome credit sequence. (Director Stanley Donen used Hepburn -- and Paris -- a lot better in "Funny Face.") Puffball commercial movies like "Charade" are pretty much why the naturalistic, low-budget French new wave happened in the first place.

Perhaps that point of view explains why I just sort of went along for the quasi-enjoyable ride in "The Truth About Charlie," crappy and nonsensical as it may be on the whole. Whereas I gather that "Charade"-lovers are likely to be highly exercised. "This was not 'Charade'!" one earnest-looking fellow in a yellow oxford shirt raged at his date on the sidewalk outside the theater. "This was the anti-'Charade'! 'Charade' was carefully constructed, and this was a total, ridiculous mess!" Consider yourselves warned by the earnest guy.

For one thing, "The Truth About Charlie" violates the nearly irrefutable Rule of Three, which holds that any movie with more than three credited screenwriters is bound to be garbage. (There are four, one of them Demme -- actually five, if you count "Charade" scripter Peter Stone). In both movies, we start off with a juiced-up plot engine, and you're at least half an hour into Demme's picture before you notice that the wheels are coming off. Cutie-pie Regina Lambert (Newton) is getting ready to dump her mysterious art-dealer husband Charles (Stephen Dillane) when she comes home to find their Paris apartment stripped to the bare walls, Charles gone, and a sexy, rather butch female cop (Christine Boisson) waiting for her.

Charles is dead, of course, and amid all the excitement Regina doesn't find it weird that an American who calls himself Joshua Peters (Wahlberg), whom she bumped into in the Caribbean, keeps turning up wherever she happens to be. This might be my central problem with both movies, actually: The Hepburn/Newton ingénue has to be a girly little dim bulb who never notices that she's super-double-obviously being followed and set up for something. Into this murk comes a crewcut-sportin' CIA-spook type (Tim Robbins) and an international, multiracial trio of thugs, all of whom evidently wanted something from Regina's defunct hubby and assume she's got it now.

Robbins goes a bit overboard with his usual shtick, as a white man oozing insincerity as thick as the scum from one of those science-project volcanoes. But as the other actors become increasingly lost in cinematographer Tak Fujimoto's welter of crooked-angle shots, crazy-making extreme-close-up conversations, and digital-video flashback and fantasy sequences, it's nice to feel as though somebody here knows what he's doing. (Boisson, who has the confidence and savoir-faire of a weatherbeaten alleycat, is also terrific.) Wahlberg, who was so essentially likable in "Boogie Nights," "Three Kings" and "The Perfect Storm," has now officially "stretched" to leading-man status with his bland, worried-looking performances here and in "Planet of the Apes." It's time to unstretch.

Really and truly, there's a lot of fun stuff here. Every time Newton goes outside in some gamine designer outfit, and the camera wanders after her, seemingly conjuring up still-beautiful specters from the cinematic past like Parisian sprites, Demme appears to forget what movie he's working on and starts to remake something good, or at least something odd: "Cleo From 5 to 7" or, possibly, "Diva." Then someone else in the story will die in some half-whimsical fashion, or will reveal that they're a totally different person from what Regina thought, and we remember where we are: a misguided reinvention of a buttoned-down romp.

Demme has floundered as a filmmaker ever since he got all respectable with the Oscar-pileup "Philadelphia" in 1993, although it might be unmerciful to hold him entirely responsible for the Oprah star vehicle of "Beloved." There's a desperation to "The Truth About Charlie" that suggests he's trying to reclaim all his "Something Wild"-era hip cachet at once by flinging a bunch of film-school tricks at the screen. You're never sure whether he's spoofing the original film relentlessly -- although the ludicrous climactic scene sure looks that way -- or trying to give it a big wet one, the way Steven Soderbergh might in his "Ocean's Eleven" mode. Like the earnest guy said, he's traded the smooth, superficial control of Donen's "Charade" for an experience that's much more anarchic and less predictable. As utterly disastrous movies go, this one's really got something.

Shares