At Kim's video store on St. Marks Place in Manhattan's East Village, the "Employee Picks" section is on the third floor, right in front of the registers and next to the new releases. In the midst of a labyrinth that only Magellan could navigate, the location of this display is one of the few things in the shop that makes sense. Not only does it give Kim's a chance to market the store's institutional knowledge to customers waiting in line; it also offers employees the chance to lure the ignorant away from blockbuster schlock and toward more complex classics.

Forget "Changing Lanes," the film buffs argue from their pedestals behind a tall maroon counter. For a real dose of class struggle, grab Brando's "On the Waterfront." Ignore "Star Wars," they demand; instead watch its epic predecessor, "The Seven Samurai."

Snobby cultural up-selling is exactly what you'd expect from a place that has "cult," "classics" and "independent" sections that each occupy twice the space allotted to new releases. But still, the rack of Kim's employee picks is full of confusing choices. If the group of 44 films is meant be a microcosm of film geek opinion, a democratic canon of the best classics new and old, then much of what was once considered important appears to have been lost.

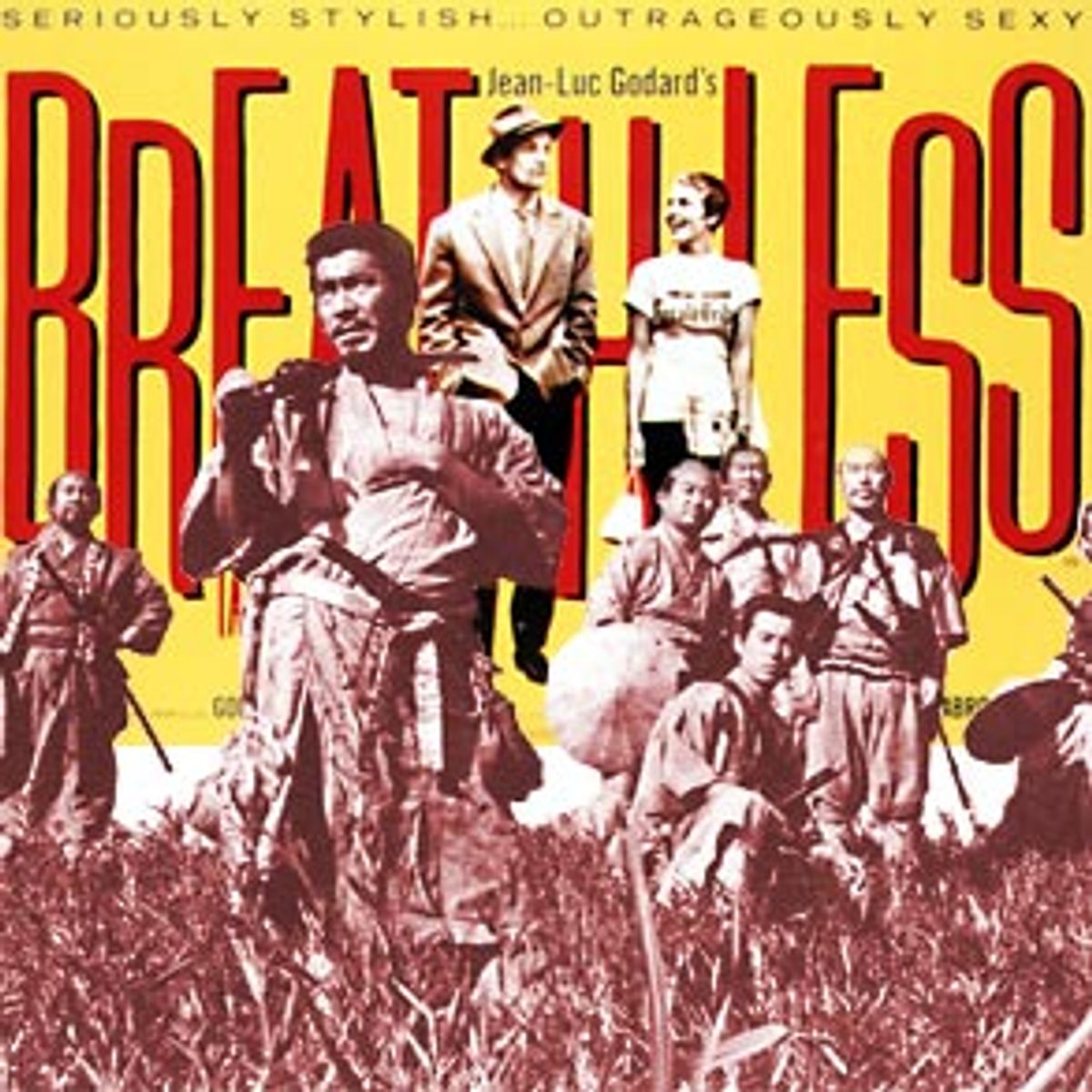

The films standing on the worn wooden shelves hail from various eras and countries. But the so-called gods of cinema are nowhere to be found. Not a single work by Italian film royalty -- Michelangelo Antonioni, Federico Fellini -- has penetrated the hearts and minds of today's self-declared film aficionados. There are no Ingmar Bergman films, nothing from classic Hollywood giants like Howard Hawks and John Ford. Jean-Luc Godard? Alain Resnais? They're not there either -- nor are they among the employee picks in the uptown branch of Kim's near Columbia University. Most of the students who rent films from the stores avoid anything made before 1970.

I ask the woman behind the counter in the East Village store -- Rachel Nelson, a 20-year-old Pace University education student with a nose ring -- why the once-essential anchors of historic cinema now seem so passé. Doesn't anyone care about Hollywood's pioneers or the complicated psychological work of French New Wave masters like Truffaut and Godard?

"I don't really like French movies," Nelson says. "A lot of them seem pretentious."

"It's easier to see something that my friends have seen," adds a 27-year-old college-educated customer standing nearby. Renting old movies, he says, "is too much of a shot in the dark."

To older film buffs and critics -- particularly baby boomers who came of age during the American film renaissance of the '60s and '70s -- such apparent lack of interest is appalling. It's nothing less than a brand of cultural illiteracy. How could anyone with a love of film remain indifferent to Godard? What kind of buffoon fails to acknowledge the genius of Ford? Clearly, pronounce the self-designated deans of film ed, the celebrity-obsessed media, MTV and college film departments -- awash in postmodern relativism that makes Spielberg as important as Bergman -- have lobotomized Generations X and Y.

"In the '60s and '70s, there was a spirit of 'challenge me, show me new limits.' People enjoyed the feeling of being lost, of not getting it," says Columbia professor Richard Peña, chairman of the New York Film Festival. "Now, 'I didn't get it' is what's said in frustrated desperation."

Is the 16-to-30-year-old crowd intellectually lazy? Not necessarily. Today's young film fans are very willing to watch the meandering montage of a film like Fellini's "8 1/2." They see the work of yesteryear's auteurs quite often, in fact, both in their film classes, which are more popular than ever at many universities, and on their own, via the Internet, cable, video or DVD. But some of these young viewers are unwilling to worship Fellini and his contemporaries with the passion of their elders. Their lack of effusive praise for the "classics," as designated by their predecessors, should not be misinterpreted as a failure to see, understand or appreciate films that were once breathlessly described as perfect. Even if they don't gush at the first frame of a black-and-white dream sequence, most young film geeks have likely learned to value Fellini, Godard, Bergman and the others who regularly appear on film critics' top 10 lists.

Today's young fanatics, like the ones who came before them, simply connect more intensely, and prefer to focus on, their own discoveries. They follow their favorite directors' influences; they find their own favorite styles and masters. Just as the employees at Kim's demonstrate impressive depth in their selection of obscure films from Germany, Russia and Japan, youthful film buffs are digging into the past -- distant and recent -- for classics of their own definition. Instead of eschewing the canon, they're expanding it. Film illiteracy is a concept subject to generational interpretation. Could it be that the old school, in clinging stubbornly to threadbare favorites, is losing its command of the cinematic language it claims to have invented?

Columbia University's introductory film class meets at 9:30 a.m. in a darkened screening room with 72 seats. Most of the students who shuffle into the class -- a half-dozen arrive late, with coffee -- seem to have just climbed out of bed. There are denim-clad freshmen without majors, and unshaven seniors who see the class as a break from their other lab or text-based courses. Shifting quietly in their seats, they all seem only mildly interested in the classic films that form the traditional backbone of cinematic history. Getting them to answer questions requires repeated prodding from Larry Engel, their compact, bright professor who spends about an hour going over last week's film, Sergei Eisenstein's silent communist propaganda vehicle "Battleship Potemkin" (1925).

But when Engel starts screening the day's films -- clips of Charlie Chaplin's "Modern Times" (1936) and "M," Fritz Lang's dark 1931 thriller -- the class seems to perk up. Eyes are wide open, students laugh at all the right places and take notes whenever Engel pipes in a comment like, "That opening is one of the best openings to a sound film, anywhere, anytime."

During the break and after class, I ask a half-dozen students what they think of older films and the idea of film literacy. A couple have a hard time explaining why they took the class, perhaps because they're half asleep or afraid to admit that they thought it would be an easy A. The others' opinions range from complete disgust with modern movies -- "I'm far more interested in the classics," says Jeansun Lee, a sophomore computer science major -- to a nuanced appreciation for certain aspects of the old.

Chris Wells, a bespectacled freshman who is considering a film major, admits that the older films are sometimes difficult to watch. "We have to learn a new language; it's like being taught to read all over again," he says. And yet, while the experience can be especially trying (he cites Godard films as an example), Wells says that he and many of his friends have learned to recognize the value of older films. "They're important because every movie today uses elements from the past," he says. "They help you understand movies of today."

Wells' interest in film started in high school when an enthusiastic English teacher screened Ernst Lubitsch's "Trouble in Paradise" (1932) and Charles Laughton's "The Night of the Hunter" (1955) -- one a romantic comedy, the other a Gothic tale of greed, both of them produced under the old Hollywood studio system. Wells immediately realized that classic cinema had something to offer. Soon he was exploring on his own, going to repertory houses, renting videos and making vigorous use of the Internet.

"The Net helped me a lot," he says. "You can find out anything about a movie from IMDB.com [the Internet Movie Database]. And what's great is that one thing leads to another. If you like one movie, you can go online and find other movies it was influenced by. There are so many paths you can go down and it's really interesting to connect the dots."

A similar level of inquisitiveness thrived in a film class for nonfilm majors at New York University. In fact, at universities across the country -- Oberlin, campuses in the University of California system, Boston College, Pomona, to name just a few -- film classes are some of the most popular offerings on campus. And like Wells, many students seem to be self-educating, connecting their own dots.

This comes through not just in face-to-face and telephone interviews with scholars and students but also, as Wells suggested, through the Internet. I posted a series of questions on message boards at IMDB.com, Google Groups, Yahoo and other sites that focus on the issue of whether old movies are still important and whether Generation X and Y lack appreciation for the "classics." The response was overwhelming. From all over the country, college students, recent graduates and high school students wrote to say that yes, most young filmgoers would rather watch "The Matrix" (1999) than "The Conversation" (1974), Francis Ford Coppola's take on the dangers of surveillance, but a growing minority want to see both.

Consider J.M. Gallegos, a recent graduate of Western Connecticut State University. Like many people his age, 25, he discovered a passion for classic cinema accidentally. "I came across 'The Third Man' one night on TV -- I think it was AMC -- about three or four years ago," says the former English major, in an e-mail he sent after finding one of my posts. "I started watching it, and as soon as I could, a day or so later, went out to rent it. It was unlike anything else I had seen before, and it opened my eyes to what film can be. After that, just like when I was introduced to classic literature in college, I began exploring older/classic films as often as I could; everything from 'The Birth of a Nation,' to 'Modern Times,' to 'Lawrence of Arabia,' to 'Chinatown.'" Now, Gallegos says, his favorites are not blockbusters but rather, "the works of Chaplin, Welles, Kurosawa, and Kubrick."

The group I met online included other equally passionate fans of classic cinema: people like J.W. Mathews, a 17-year-old high school senior in Amherst, Mass., who lists Truffaut's "The 400 Blows," Kurosawa's "The Seven Sumurai," and Welles' "Citizen Kane" on his list of top 20 favorite films; and an anonymous teenager who wrote to say that he has seen every film on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 Greatest American Movies of All-Time.

A. Madison, an archaeology major at Arizona State, said that "most of what I know about movies I learned on my own -- either through watching them or reading something about them." There was also a 16-year-old high school student who, after watching "The Apartment" in class, says that now "encouraging classic film appreciation among my peers is a secret agenda of mine"; and Kyle, an 18-year-old college freshman, who insisted that "to appreciate film's full capabilities you should see the widest varieties of genres and nationalities. American, German, Italian, Japanese, French, British -- you name it, any kind of cinema."

All of these people in their teens and 20s -- along with a handful of older film scholars who argue that today's young people are at least as fascinated by classic films as their predecessors were -- say that their appreciation can be attributed to the availability of film and a process of acquired taste that comes from exposure to an eclectic bunch of movies. With cable, video, DVD and the rise of restored film prints like those put out by Rialto Pictures, "kids can self-educate," says Jeanine Basinger, head of the film program at Wesleyan University. "They didn't have film Ph.D.s when I was learning about film in the '50s," and film buffs had to explore on their own, Basinger says. "Today's kids are returning to that ideal."

Today's students of film are coming of age in a time when independent cinema has catapulted out of the art houses and into the mainstream. The movie industry's burgeoning faith in independent and edgy film has brought everything from "sex, lies, & videotape" to "Mulholland Drive" to local cineplexes, creating a willingness in young audiences to see films that, in an earlier era, might have been categorized as dull or incomprehensible.

"The more popular contemporary movies in my circle of friends are the movies that are more challenging; the ones that are doing something offbeat or different in a narrative or visual sense -- like anything by David Finch or Wes Anderson, or Richard Linklater's 'Waking Life,'" says Kate Brokaw, a freshman at Pomona College in Claremont, Calif. "We're part of that trend that's looking for something different, and it makes us more willing to dig back into the past for older innovative work."

Most students and recent college graduates are lured back to traditional classics by their interest in current hits or cult films. They discover a contemporary director that they like, then trace his or her influences. Wes Anderson's "Rushmore," for example, led Wells back to the directors of the French New Wave -- Godard, Rivette, Chabrol, Varda. "The success of Tarantino's work raised up Asian cinema," says Bruce Jenkins, director of the Harvard Film Archive. "People weren't talking about John Woo before 'Reservoir Dogs.' And 'Run Lola Run' is a great film that knits together German legend with a very contemporary subject. If the director [Tom Tykwer] can do what he did with an old subject, people wonder, what was [F.W.] Murnau [the director of "Nosferatu," a 1922 vampire story that was also the subject of 2000's "Shadow of the Vampire"] doing in the '20s?"

But if German and Japanese films are hot -- which is the case not just at the Harvard Film Archive but also at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, Calif., and at universities such as Wesleyan -- what kinds of films are they replacing? Have classics considered crucial by aging film buffs fallen from favor?

The students, professors and young film geeks I queried admitted that Bergman, Antonioni, Fellini and Godard had lost their status in the classics lineup. However, Ray Carney, a film professor at Boston University who maintains a comprehensive Web site on film and other arts, believes that simply citing names doesn't fully explain what's happening. It's a certain style of film that today's audiences seem unable to grasp, he says. The "spiritual" films have been shoved aside, explains Carney -- those that offer "a transformative experience," those that "expose us to new ways of being and feeling and knowing."

It isn't so much about the directors, says the film professor; it isn't just the old ones who get the boot. While Antonioni's and Bergman's work from 40 years ago fit Carney's description of unfavored films, he also cites the work of '70s indie heroes like John Cassavetes and relative newcomers like Abbas Kiarostami ("A Taste of Cherry," 1997), Mike Leigh ("Secrets and Lies," 1996) and Todd Haynes ("Velvet Goldmine," 1998).

The key issue with these films, Carney says, is that "you don't get easy gratification out of them. You're often left puzzled or frustrated. You may have to see them a second or third or fifth time." And precisely because they're difficult, says Carney, a caustic critic of academic multiculturalism and the press, they're eliminated from curricula and today's updated canon. Film culture's gatekeepers (except at Boston University, Carney says) favor films that fit easily into a political agenda -- Who's being oppressed? What would Marx think? -- or have an ironic, pop-cultural and literal sense of art. A film like Cassavetes' "A Woman Under the Influence" -- the story of a woman's struggle with mental illness and her husband's unorthodox attempts to keep her sane -- can't be explained by these postmodern theories, Carney says, so it's dropped.

"I was at the Stanford film department, at Middlebury, at the University of Texas, and no one recognized [Cassavetes'] work," says Carney, who was a personal friend of the filmmaker. "It wasn't, 'Oh, we show it sometimes'; it was blank stares. They all thought he was just an actor in 'Rosemary's Baby.'"

To Carney, the contemporary filmmakers that many students cite as their favorites -- Wes Anderson, Richard Linklater, Todd Solondz -- lack depth. Just as kids in the '60s were attracted to "Bonnie and Clyde," "Easy Rider" and other anti-establishment pictures, today's kids are attracted to movies that show what Carney calls "the dirty underwear of American culture."

"It's not bad in itself," Carney says. "'Magnolia' is a better film than 'Titanic.' But it reveals an institutional bias to show films that pander to the youthful desire to drop out, or believe that the world is a load of crap."

Other insightful critics, like Peña at Columbia, agree with Carney's pessimistic take on today's budding film buffs. And they seem to be correct in pointing out that scores of young film fans fail to worship the baby boomers' gods -- Bergman is a classic example -- with the same intensity their parents did. "Even Fellini, who was who I loved when I was young, isn't as relevant anymore," says Richard Breyer, a film professor at Syracuse.

It's also true, as Carney suggests, that some undergraduate film programs have shifted their curriculum to fall in line with what students and academics now find attractive. Syracuse, for example, now offers a Shakespeare-in-film class because students have become fascinated with recent bardic adaptations like Baz Luhrmann's "Romeo + Juliet."

Meanwhile, Bergman and Antonioni films, says Breyer, "are out of the house." Even at NYU, the introductory film course I visited was not a broad survey of brilliance but rather a study of Hitchcock's films, which are still popular today in part, if Carney is to be believed, because they're suspenseful enough to hold students' attention.

Carney's larger argument about German and Japanese films -- that they're favored because they're less challenging -- isn't entirely off base, either. As Basinger at Wesleyan points out, films from both of these countries are closely related to the Hollywood style we've been trained to watch. Early Japanese movies like Kurosawa's "The Seven Samurai" (1954) resemble refashioned westerns, and the style of German expressionism essentially became part of the Hollywood repertoire when Hitchcock, and Austrians like Billy Wilder ("Double Indemnity," 1944) and Fritz Lang ("The Big Heat," 1953), emigrated to join the studio system.

And yet there are several holes in the pessimists' theory. The idea that German and Japanese cinema is inherently superficial because it's familiar and Hollywood-like -- an overgeneralization in its own right -- is a bit like saying that "The Great Gatsby" is shallow because it resembles British Victorian novels that concerned themselves with class and social striving. And even if German and Japanese cinema works within a tradition that young Americans easily comprehend, can it be inferred that the films themselves are less "spiritual" or important? If students are finding those films interesting, does it mean they're less willing to watch other kinds of difficult older films?

Rather than cutting out the older classics from curricula in favor of films that are easy to watch or politically relevant, colleges (and high schools) have actually added films to class viewing schedules -- and film courses to their catalogs. Even small schools like Oberlin have recently made film a fully developed, expansive major so that these days, if students haven't already seen Fellini or Howard Hawks films on their own -- and many of them have, according to Basinger -- they'll likely get the chance to catch up in architecture in film, which is being taught at Cooper Union, or the Italian realists class at Columbia.

And even if there are some students who won't watch any Godard in their films of Weimar Germany class at the University of Montana, there are others who will be introduced to "Vivre Sa Vie" (1963) -- Godard's episodic tale of a Paris prostitute -- in NYU's Hitchcock class, where professor Richard Allen uses the film to show what can be done with ambient sound. Sure, in some cases, the films will be seen through the lens of political theory, feminist theory or Jacques Derrida's frustrating form of deconstruction, but the films are still being seen -- and that includes the "spiritual" ones that Carney feels have fallen into the abyss. As Annette Insdorf, chairwoman of Columbia's undergraduate film program, points out, "There is renewed interest in mavericks like John Cassavetes, now that the independent American cinema is virtually a genre."

So why are baby-boomer critics panicking about the film literacy of younger film addicts?

Partly, says Basinger, it's simply nostalgia: "There's always the assumption that the younger generation A) has no intellectual curiosity; B) won't explore the past; and C) won't notice something good when it's put in front of them."

Older critics who came of age during the era of revival houses, like those described in Theodore Roszak's brilliant novel "Flicker," may also be mistaking shifts in technology for shifts in literacy. "What they remember about the '60s and '70s was that excitement, and revival houses and community," Basinger says. "The fact that kids pop in a DVD and watch it quietly -- it seems different. But it is the same, in a different form. They're missing the group camaraderie, but that doesn't mean that passion isn't there, or the interest isn't there."

In addition, the shift away from European directors that Syracuse's Breyer described seems to have been misinterpreted. It's not that students don't watch Fellini anymore. As Bruce Goldstein, director of repertory programming at FilmForum in New York, points out, the mix of young and old for a Fellini retrospective today is essentially what it was 25 years ago. But certain films seem to age better than others. "Nights of Cabiria" was a favorite of many students I interviewed, while "8 1/2" was off their radars. Both are available on DVD, so it's not a distribution issue. But critics who hear a student disparaging the latter often take this to mean that today's young audiences are unable to appreciate Fellini. And yet there are other explanations: Perhaps, for instance, "Cabiria's" Forrest Gump-like inginue simply resonates more intensely than the Freudian tale of a frustrated filmmaker in "8 1/2."

At the same time, is Gallegos (the one who accidentally discovered "The Third Man") film illiterate because, as he puts it, "I have always been as receptive to Far Eastern cinema (Kurosawa and Ozu) as most film buffs have been to European cinema"? After all, he still watches and understands Fellini; he just doesn't like it as much as his elders do. At what point does criticism of what people read or watch become an excuse to pressure us all into liking the same books or movies? At what point does the idea of a canon cease to be an educational tool, becoming instead a shackle of approved taste? Or a bid for legitimacy from an older, and increasingly cranky, generation of film fans?

Gallegos and other smart 16- to 30-year-old film geeks, don't much care. They simply emphasize that they're seeking their own examples of greatness. Not content to just see and appreciate what their parents loved, they're aiming to deify their own directors, create their own canon.

Which brings us back to the bin at Kim's. It's chock-full of Asian, German, African and Russian cinema. Documentaries, once shunned as less artistic than features, are also there. And with choices ranging from "Come and See," a 1985 Soviet film about World War II, to "The Tokyo Olympiad," a lengthy documentary about the 1964 Olympics, the display presents not just options, but intelligence. Are they spiritual? Probably depends on who you ask. Are they important? Same answer. At least they're undiscovered, says Nelson, the nose-ringed clerk.

"The picks are a way to suggest movies people probably haven't seen," she says. "People know Godard -- they want something new."

Shares