Anne Lamott is a collection of contradictions, but perhaps the most remarkable among them is the fact that she helps her readers carry on by writing about almost falling apart. The heroine of her new novel, "Blue Shoe," is Mattie -- in her late 30s, freshly divorced, practically broke, raising two kids and worrying about her mother's failing health. Her ex-husband is remarrying (to a woman in her 20s), she's got a wicked crush on a married man and she's starting to think there was more to her late father than met the eye. Although the novel's significant plot points aren't autobiographical, fans of Lamott's Salon column will recognize a few favorite scenes from the author's own life, including a painfully funny visit to Safeway and the return of Otis, an exceptionally charismatic iguana. (These same fans will be delighted to hear that Lamott will revive her Salon column in the near future.)

"Blue Shoe" is a novel that unfolds to the rhythm of the seasons in West Marin County, Calif., where Lamott lives, and takes its heroine through several crises and revelations before its end. It has all the elements Lamott's loyal readers have learned to savor, the piquant combination of spiritual reflection and biting wit, the unabashed political commitment and the delicate observation of domestic life, but most of all it has the honesty that her fans have come to cherish not just in her fiction, but in her popular nonfiction books on writing ("Bird by Bird") and motherhood ("Operating Instructions"), as well. "My message," she says, "really is of hope, too, because if I can get through it really anyone can because I am so much more tenser than the average bear."

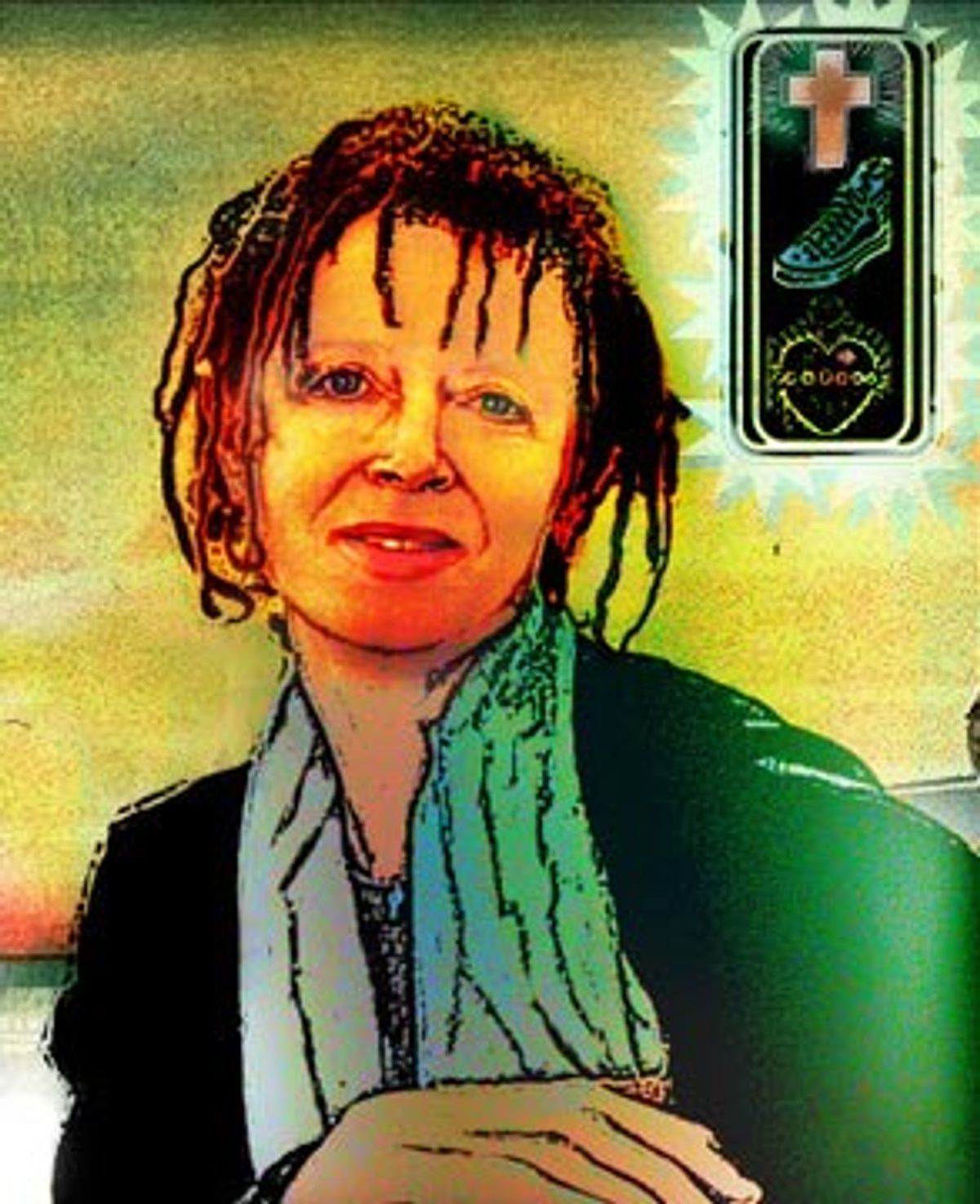

Lamott stopped by Salon's New York office recently to talk about "Blue Shoe," family secrets and where she intends to hang out when she gets to heaven.

What was the motivating idea behind "Blue Shoe"?

The motivating idea was that I'd been working for Salon for a really long time. Every couple of weeks I did a piece on whatever I wanted. It's been a great place for me to develop material. I've been able to try out things here and there, scenes that I didn't want to forget, in between left-wing screeds and proselytizing. I put together "Travelling Mercies" almost entirely from Salon essays. I had the intention of getting a lot of early work done on the novel in the same way because it's so safe for me. Instead of this big unassaulted iceberg of a novel it would just be five pages every two weeks.

A lot of my favorite set pieces are in "Blue Shoe" -- like the iguana Otis and the mother shopping at Safeway with her coupons and didgeridoo stuff -- really odd, unlikely stuff I wrote there. And I could tell it was good because I had five days to write five pages and get it right. I didn't have the stamina to tackle a novel for a long time. I just kept writing scenes, a lot of stuff about Marin and West Marin, where I live.

Little by little I felt like something was tugging on my sleeve. I really don't like to write novels at all. I'm really not impressed with my own novels. This character started appearing, and then I found this little blue shoe that I'd gotten in a gumball machine 20-some years ago with an old friend. We'd found it at a really hard time for both of us. Right when [my novel] "Rosie" was getting rejected and Viking had said, "This will never get published. It's a book you wrote to get out of the way." Of course, I'd spent the advance, which was $7,500. I had no income, I was a total drunk. I was just so devastated.

I moved in with a divorced friend and while we were at a market I put 25 cents in a gumball machine and out came this plastic ball with this stupid, nothing, little turquoise rubber shoe with perfectly delineated laces and a round logo. It's a high-top. I thought it was a Ked, but if you mention this to men there's extreme agitation until it's settled that it's a Converse.

Then I thought what a nice way to tell this story that I basically tell in different forms which is that our only hope is that some of us take care of the others. And that some people take care of me, that I let them know me and they love me anyway. And they show me their most awful stuff and I just love them more. When Pat and I were staying in the same house, when things were bad for me, I'd get the little blue shoe. It was so soft and when you curled your fingers around it, you just felt like you could breathe again because you had something to hold onto. It was nuts -- and obviously I was in some sort of alcoholic breakdown, too -- but that's another story because Pat wasn't, and when things turned bad in her life, I left her a note saying: "I think you need this for a while. And I just want you to know that I'm going to walk you through this. Stay on the train, the scenery will change."

So it worked for her too? She was your control group.

Yes. She was working in the city as an executive, with the fancy nails and fancy clothes, but every day when she left for work I knew the secret, which was that she was clutching the little blue shoe. It's a hard and sometimes horrible world, and it's good to have something to hold onto. One day I came home and she was vacuuming and I said, "How are you?" She looked at me and without saying a word unrolled her fingers. She was vacuuming clutching the little blue shoe. When I was going through a hard time, I'd wake up and there'd be a note saying, "Don't worry, I'll be here every step of the way, and the shoe is there."

I thought what a great way to tell the story of a friendship, from the first time you see somebody at the door that you recognize in some deep, subconscious way, when something inside you is stirred. What a way to tell the story of a friendship that grows organically from that, with two friends trading back and forth a shoe that's worthless to the world, but that says to each other that they'll really be there. Every chapter ends with the trading of the little blue shoe to the person who needs it more.

Once I had that in place, I took a deep breath and said, "I think I'm going to have a novel," the way people say "I think I'm going to have a baby."

Was it as hard for you to put this book together as your earlier novels were, or did having the theme and some of the scenes already make it easier?

No, but I have a very hard time. It's slow. People say, "Oh, it sounds so natural!" but that's four drafts down the line. The first draft is so hysterical and bitter and overwrought. And it's all this attack on the right wing. But somewhere in there is a bead that I've created that's a scene and can be strung on the cord. It's hard, and novels are hard. I don't know who I am a lot of times, as a writer. I know that I can make people laugh. I know that I have a good eye for stories that surprise you because they seem at first to be all hopeless which is how I feel about a third of the time and they turn out to be kind of funny and even touching. Or they break the trance of busyness that you're in.

The first draft of the Salon pieces would take two days, and then I could really get down and burnish it. A lot of my creativity is in taking things out because I tend to write too long and talk too long. Then the fourth day I would get to get it just right. But a novel takes me a whole year to even know the characters, and every step of the way I think, This is so hopeless. By Page 8, I'm so obsessed with whether [New York Times book critic] Michiko Kakutani is going to dislike it, even though they've never actually given me a daily review. I'm worried about whether these people who have never deigned to give me a review are going to like it or not. I get up to look at CNN every hour. I bribe myself with that. I always think that George Bush is going to have a moment of conscience and realize that he didn't actually win the election and he should just step down.

That usually doesn't happen, and then I get back to work. During the O.J. trial I used to bribe myself by saying, "If you just go and write this scene out at Samuel P. Taylor Park, inside that old redwood tree, then we'll stop and go see if O.J. has confessed," which he usually hadn't either.

So I use bribes and threats, and after a year I know the characters, it's way too long, it's all over the place. It took a year to find that there were three strands in "Blue Shoe" that were a weave. One was the story of Mattie's life going up in flames. Her world has crashed and is burning, her marriage is over, her husband is in love with a girl in her early 20s. And Mattie's getting bigger and grayer and like the rest of us just a tiny, tiny bit more wrinkly with every passing day. She has two kids who have been through the smash-up of divorce and separation even if it's for the good. And she's got a mother who's clearly got some form of dementia.

So there's Mattie's mother and the wreckage of a family; there's this man who she sort of recognizes somehow who appears on her doorstep -- that's the love story. And then quite early on she and her brother, who's her great advantage in the world, end up with this Ziploc bag of dumb trinkets and a library that belonged to her father, and in it is this little rubber blue shoe. And that's what gets them to thinking, Why would Dad have this stupid little blue shoe? It's a search for clues into who he was and why everything was so not what it seemed when she was a child, why she was so worried and had to be a black-belt codependent by 9 years old to feel she had any value at all.

It's so common, when a parent dies, for the adult children to get to talking with the parent's friends and, even if there's no big secret to discover, to get a totally different picture of who the parent was from that conversation. And the friends are often surprised about how the children see their parents. Is that the kind of experience that inspired this novel?

None of the plot stuff really happened. OK, some of the awful men, oh, are a little tiny bit true. And emotionally, psychologically and spiritually all of Mattie is me, obviously. But most of the stuff that happens to her didn't really happen to me, although my mother did die of Alzheimer's and a little of what happened to her there happened to me.

There was no one trinket that symbolized it or anything like that but it's true that after my parents were both dead, I'd say, "My mom was just insane." And it's true, she was insane in a very socially sanctioned way, kind of pathological, like a lot of women were before the women's movement. People would say, "You're so exaggerating it. Your mother loved so much about life." Well then why did my mother weigh 200 pounds and why was she so frantic and so scary? I'm not exaggerating. People would say, "Oh, I think there was a lot of mutual respect," but that was the performance art of their marriage. The guests left, and the door shut and the sulks and the snits and the small explosions began.

I think almost every kid I know had that experience where from the outside they seemed like a wonderful ideal family, but on the inside ... I had this one friend whose father was the mayor of a small town, really a perfect civic leader, charming, witty and involved. And the kids just went to the hospital all the time because the father broke their bones. He tried to hit them where it wouldn't show.

My parents had a disastrous marriage. Inside the house there was this whole reality unfolding that was a lot about secrets and drinking and my dad and mom not talking to each other very much. My father didn't speak to my mother very much and when he did it was this sort of Harold Pinter clippage. We were all using drugs pretty early and we were all encouraged to drink, but when we stepped outside we were fabulous. I was a tennis star; my dad was a well-known writer, really smart and handsome in the Kennedy mode.

What happens in Mattie's family is more overtly distressing than what happened in mine, but mine was chronically distressing. I had migraines from about 5 years old until I was about 17 or 18, I think, when, coincidentally, I left home. I grew up putting my head on cool tiles in tennis clubs, and it didn't occur to anyone that there was something really traumatic going on for me that was manifesting in a really flagrant way. My head was splitting open. I had a caseload at 6 years old. I was a marriage counselor, I was trying to raise my brothers -- the nanny, the governess -- I was my father's main date when he went places.

There were no divorced families when I was a kid. It was so important that you not be divorced. I would do whatever I could to make sure Dad kept coming home. At 40 pounds, I would be trying to get a heavy-drinking, unfaithful, man-about-town writer to come home every night. It took a tremendous psychic cost. My brothers and I were the most worried people on earth. That's a theme that I've written about, but I wanted to write a novel about it.

It's no wonder, then, that in your writing -- fiction and nonfiction -- you've been so concerned with describing what things are really like. You can see the tension between what you think you should be feeling or doing and what's actually going on. That's an enduring theme for you.

It is. I'm so relieved when people will tell the truth because I grew up thinking I was in an alternate reality. And right now, with Bush in office and especially the first six months after Sept. 11, I felt like I was in an alternate universe. I would speak out, because I have a big mouth, but I felt like nothing anyone is saying is true. The culture mostly has total bullshit, some of it very nicely tricked out with curtains and fresh paint, to offer. When I read a book and somebody's telling the truth, I feel like I can breathe again.

Mattie is so faithful, very political and so loving with those children. She's such a good mom, and yet at one point, with something so little, which is that they don't want more reading light, she puts her fist through the wall. Or with her mother going down the tubes and being so pitiful and vulnerable, she should feel like she does when her little dog is dying, but instead she wants to choke her mother.

That's why I wrote "Operating Instructions" -- or why I published it, because I was already keeping a journal. All the baby books out there were so full of happy horseshit, like you should be like Marmee in "Little Women." You would surely feel a lot calmer if you would just rock the baby, but the fucking baby won't go to sleep and it's 10 p.m. and he's been crying for five hours and you're alone and your body is still hurting from childbirth and you don't have enough money and the baby won't shut up.

When I would talk to other mothers, they'd say, "We're all nuts about a third of the time and we all realize that we really don't want children and don't like children. It's like having little mental patients -- or little tiny alcoholics -- living with you." And when people would tell me that, I'd feel like I could breathe again. Thank you. Of course, the truth people won't tell you is always kind of unpleasant. Yes, moms are pushed to the brink and they stuff a lot of it, and then there's a limit and they blow. The mothers blow. It just happens. Do you know that book "Lucky in the Corner" by Carol Anshaw?

Suzy Hansen reviewed that book for Salon.

I loved that book. I've bought copies for people. It's about such a mess of a family, and because of that it felt so real. They stick together and they do the best they can and the message is, "I have hope that if this character can get through this, you can, too." My message really is of hope, too, because if I can get through it, really anyone can because I am so much more tenser than the average bear. But you might need help, you might need someone to do it with. When I read that book, I felt like my gas tank was filling up, someone was just telling it in a way that I could recognize myself and get lost in how funny and what a wonderful writer she is. And I was getting found because it rang true, and so little rings true for me. I happen to really love that book.

How do you feel about writing fiction compared to writing nonfiction?

It's just so much easier for me to write nonfiction. And if you think about it, all three of my nonfiction books, which have been much more popular than my fiction, have been short takes strung together on a cord. "Operating Instructions" was daily journal writing. "Bird by Bird" was a talk I'd been giving for years. If they gave me a full hour, it was called "Everything I Know About Writing," and if they gave me a half-hour it was called "Almost Everything I Know About Writing." The chapters in "Bird by Bird" were just the notes to myself of areas I wanted to cover. "Travelling Mercies" was Salon pieces. I had several years' worth of pieces to choose from, though.

It really goes back to the stamina issue. I really love nonfiction, and I read a lot of it. I read a lot of religious stuff, Buddhist stuff. But my great love is fiction. It's what I loved as a child. Pippi Longstocking, E.B. White -- these people who made you feel as if it was going to be OK. I love that feeling that someone has created a world behind the door to the secret room, and they've gotten the details just right and they've told it the best they can. It's this world that you can enter into and then pull the rabbit hole in after you and then be there. It's saved me over the years. Fiction has saved me in the same way the Bible has. In fiction I can find a greater truth than in nonfiction.

As a writer or as a reader?

As a reader. I'm not sure about the nonfiction writing ... because it was really easy. "Operating Instructions" really was a journal. It was really easy to get it down. "Traveling Mercies" was Salon columns. I noticed that a lot of them were about the spiritual in the ordinary stories of the day and so I got the idea of a book of essays that I'd love to come upon, by someone who was religious but really crabby and who could make me laugh and didn't take herself seriously and who didn't feel like she had any lock on the truth, who knew that you couldn't.

There's this great joke about a man who dies and goes to heaven and is being shown around by the angels who are saying, "Over there are the rolling hills where it's balmy and sweet, and over there are the mountains with clouds and rain for people who like to be indoors by the fire, and there's meadows and a huge pond over there," and it goes on and on. And then there's this walled-off compound and the guy says, "What's that?" And the angel says, "Oh, that's where we put the fundamentalists. It's not heaven for them if they think anyone else got in." I'm a Christian who knows that everyone gets in. In fact, I want to be with the smokers and the Jews because I think they're inherently more interesting.

Shares