Each generation has its anti-cartoonist cartoonist, the lone genius whom almost everyone -- whether they read comics, like comics or even know anything at all about comics -- seem to know and like and consider respectable. Part of the problem with acquiring comics, as opposed to perfect-bound novels, is one of access: Most single-issue comics are available only in comic-book stores. It's difficult enough to find the kind of stores that stock the good, arty comics in the first place; those that do will often find that the merchandise is more often than not guarded by surly men in metal-head T-shirts who don't take kindly to the uninitiated.

There is no good reason why anyone who reads good fiction should not have a fat bookshelf exclusively devoted to comics. But it often takes the cultural equivalent of a divine proclamation to get the squeamish to take a novel with pictures seriously. It took a Pulitzer to make Art Spiegelman the "lone genius" of the last generation. And it took a surprise hit movie to make Daniel Clowes the next beloved cartoonist for people who think they don't like cartoonists (though Chris Ware, whose "Jimmy Corrigan" was the first graphic novel to win the Guardian First Book Award, isn't far behind). It is probably safe to say that all across the country, there are readers who have bought exactly two graphic novels in the last 15 years: Spiegelman's "Maus" and now Clowes' "Ghost World."

Most of those same readers who discovered Clowes via the local multiplex have probably not yet read "Eightball," the comic Clowes has been publishing since 1988 and the place where "Ghost World" first appeared in serialized form. Within the comics community, "Eightball" needs no introduction; like Spiegelman's "Raw," it is considered a modern classic, so well-known and indisputably good that the only still vital question is whether it is overexposed and thus prone to an insider backlash.

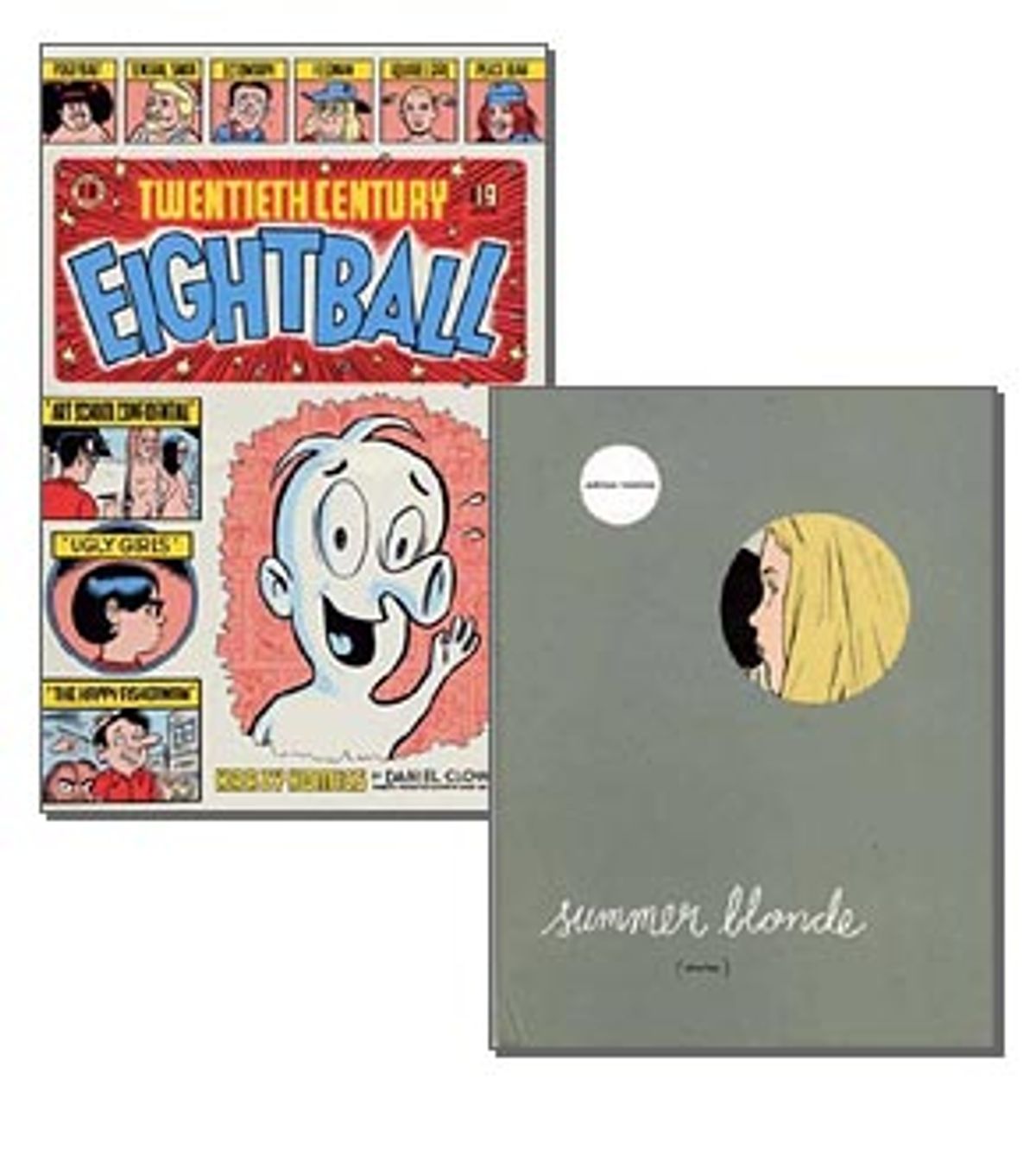

Those who missed out on the first 12 years of "Eightball" can find it in "Twentieth Century Eightball," available in attractively bound book form, most likely even in those stores that do not have a graphic-novel section. (Over the years, I have found "Maus" shelved under "fiction," "literature," "nonfiction," "world history" and "Holocaust.")

Clowes' reputation is based on writing the graphic equivalent of literary short stories and novels; these are the kinds of stories that would have made the New Yorker were it not for the pictures (though of course several of Clowes' strips as well as his illustrations have made the New Yorker). Besides "Ghost World," Clowes' work includes three previous fat and delicious works of fiction -- "David Boring," "Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron" and last year's short-story collection, "Caricature: Nine Stories," all of which appeared previously, in some form, in "Eightball." These stories are complex, sustained works and prove Clowes to be the equal of the best fiction writers working today.

"Twentieth Century Eightball" is made up of the rest. Clowes describes them in his self-deprecating introduction as "what we in the business refer to as 'filler' strips or 'bullshit' strips or 'slap the first stupid idea you have down on the page because it really, truly doesn't matter to anyone at all' strips." (The title page of "Twentieth Century Eightball" bears the byline "Krazy Komics by Daniel Clowes, formerly respected author of 'Ghost World.'")

These strips range from autobiography to short character sketches to social satire. Many of the pieces are classic comics -- full of ectomorphic characters with weirdly shaped heads inhabiting fantasy landscapes: post-nuclear wastelands, outer space and the like. But they are far from being "bullshit" strips. The best are easily as testily thoughtful and revealing as Clowes' works of fiction. And if they aren't concerned with creating sustained narrative story lines, taken together they do tell us a lot about character -- though the character revealed most is Daniel Clowes (represented either as himself or via a "transparent stand-in" in roughly half of the pieces).

In contrast to his graphic novels, these strips resemble a Clowes manifesto, or perhaps the notes scrawled by his psychoanalyst. (Said analyst would probably have much to say about "The Happy Fisherman," about a guy who walks around with a frozen fish stuck to his dick, "Ink Studs," in which a penis serves as a paintbrush, and "Needledick, the Bug Fucker," which is exactly what it sounds like.)

Perhaps the most striking thing about "Ghost World" -- the novel and the film -- was how relentlessly Clowes refused to permit anything to exist in Enid's world that was as lovable, quirky and authentic as Enid herself. (Since Clowes authored the novel, and co-authored the screenplay with Terry Zwigoff some plot elements of each are mixed freely.) Enid wasn't just stuck in anonymous suburban strip-mall hell with dopey high school boys, bad fake blues bands, and no clear future to aspire toward. But even the traditional nests for losers and freaks and "artists" seemed to have been recycled past the point of redemption: Her "original punk rock" look was misinterpreted as "trendy" and the coffee houses were loaded with alterna-rock-boy poseurs. Meanwhile her best friend Becky was being seduced by Crate and Barrel and her neurotic, older-guy record-collector friend turned out to be susceptible to the charms of a peroxide-blond realtor. Even art school was out -- the domain of solipsistic "performance artists" and those canny students who get brownie points for cynically regurgitating the zeitgeist on a platter.

"Ghost World," like just about every competent adolescent coming-of-age story, has been likened to "Catcher in the Rye." The comparison is apt in the sense that, to Enid, pretty much the whole world has become the kind of place where a beloved older brother has to switch from literary fiction to advertising copy as the cost of becoming an adult. In the graphic novel, Clowes even shows himself and his work as an object of Enid's ridicule; she shows up at one of his signings, only to find out that he is some pathetic old guy.

The stories in "Twentieth Century Eightball" are no more forgiving -- frenzied, neurotic and filled with self-loathing. There are strips about the fruitlessness of the search for love, creating art, being a Christian, being a devil worshipper, being an agnostic, being a hippie, being a businessman and living in Chicago -- where "a special circle of hell is reserved [in which] the damned will be forced to drink old-style beer while listening to an eternal medley of R&B standards performed by Jim Belushi and Bruce Willis (on harmonica)." More than one strip ends with a character putting a gun to his mouth. Though even suicide makes for a drab option: In "My Suicide," Clowes points out that, should one do the deed, "very few people would feel bad for more than a day or two (if at all)."

Despite (or perhaps because of) this relentless nihilism, many of Clowes' strips are scathingly, brilliantly funny. "Why I Hate Christians" and a companion piece, "Devil Doll," are witty satires of the fire-and-brimstone rumblings of the religious right, popularized in fundamentalist Jack Chick's cartoons threatening eternal damnation. "On Sports" offers Freudian deconstructions of such popular games as football ("sublimated homosexual rape and Oedipal hostility"), baseball ("again the player is fucking, though not so much his opponent as the field ... itself"). If you can imagine what the illustrations depict, it won't be difficult to understand why this strip prompted a boycott when it appeared in an Austin alternative weekly.

Many readers will recognize several characters from "Ghost World," the movie, including Feldman, the annoying guy in the wheelchair with the laptop connection, who is stalked by SquirrelGirl and Candypants, teenage girls on the Enid and Becky model. The best of these strips is "Art School Confidential," which has been optioned as a feature film, a story about the futility and silliness of art school, based on Clowes' years at Parsons. In this strip, Clowes takes on pretty much every kind of art (trashed dorm rooms and toothbrushes as final projects; the "famous tampon in a teacup trick") and artist ("Mr. Phantasy," who "does a Frazetta-style painting of a barbarian as the solution to every assignment" and the guy who draws his girlfriend in "humiliating, sexually submissive poses, then brings her to class with him.")

But for all his cynicism, Clowes offers many moments of compassion, even beauty. "Ugly Girls" is an ode to the kind of cute girl with big teeth, glasses and plaid skirts who so often shows up as a Clowes' heroine. "When I see a 'beautiful' woman," writes Clowes, "I'm usually bowled over by existential boredom ... True physical beauty must be that perfect combination of natural and chosen elements, which fall together ... suggesting something beyond the physical."

And in the aptly named "Marooned on a Desert Island with the People on the Subway," Clowes spins a strangely touching fantasy of how, exactly, the 10 or so people on his train car would re-create civilization were they to be, you know, stranded on a desert island. Will the cute blonde choose the young wanker, or will the businessman get all the chicks? Can the professorial-looking guy make a ham radio out of that high school kid's Walkman? By the end of the strip, when he has planned how they will care for the second generation of desert island inhabitants, one feels a certain genuine grief that the weird community he has imagined for them will never be, or at least that none of the people who share his car know that the cranky guy in the corner has been studying them with such a shrewd and compassionate eye.

Those in search of the next lone genius or those looking for a gorgeous collection of literary short stories would also do well to pick up "Summer Blonde," the latest hardbound collection by Adrian Tomine (pronounced "Toe-Mean-uh"). Though Tomine is only 28, this is the third collection of stories taken from his comic, "Optic Nerve," which he has been publishing since age 16. (Tomine self-published until 1994, when the Canadian publisher Drawn and Quarterly signed him up while he was an undergraduate at the University of California at Berkeley.)

Tomine's illustrations regularly appear in the New Yorker, and "Bomb Scare," a story from this book, was included in the "Best American Nonrequired Reading" anthology, edited by Dave Eggers (though a reference to fisting and the last panel, which contained nudity, had been removed). He's already been around long enough to inspire a mini-backlash from those indie purists who say his best work is behind him.

Tomine's work is aimed at the same audience as Clowes'. (In fact, the two are good friends and lived for many years on the same street in Berkeley.) Although many alternative writers go through a superhero or supernatural phase, "Optic Nerve" has from the beginning been almost exclusively devoted to realistic, impeccably drawn short fiction, usually about relatively young urban characters casting about for their place in the world.

Tomine is a master of the arts of both cartooning and fiction, and he uses each to complement the other. His panels are meticulously, nearly obsessively perfect, and his freakishly accurate mastery of human facial expressions means that many times, he is able to forgo lengthy plot explication altogether and say it all with spare dialogue and a glance or gesture. It makes one wish that MFA students intent on writing minimalist fiction would simply get themselves to the drawing board instead.

On the comics shelf

Eightball #22 by Daniel Clowes, Fantagraphics Books

Twenty-nine interlocking stories follow a Leopold and Loeb-inspired kidnapping in a small town and examine various characters along the way -- a frustrated poet, a teenage bride, an anti-Semitic school bully, a kid in love with his older stepsister and a teen 'zine genius.

Love and Rockets #5 & 6 by Los Bros Hernandez

Jaime's Maggie and Hopey deal with Izzy's psychotic episodes, while Gilbert offers a sympathetic and disturbing portrait of Fritzi's teenage sexual escapades as the girl with the big boobs whom everyone wants to do but no one wants to date.

La Perdida #2 by Jessica Abel

Abel, the creator of Artbabe, has produced a striking series about Carla, a girl who decides to go from Kansas City to Mexico City to discover her "roots." In this episode, Carla ditches her trustafarian sort-of boyfriend for a goateed revolutionary, while her communist friend continues to berate her for thinking she can discover her authentic Mexican self in pretty pottery and peasant costumes.

B. Krigstein by Greg Sardowski, Fantagraphics

A lush, coffee-table retrospective of the work of Bernard Krigstein, the classically trained painter who became one of the most influential and innovative comics artists of all time during his period at EC Comics in the '40s and '50s.

Three Fingers by Rich Koslowski, Top Shelf

An amusing Ken Burns-style faux documentary about the early days of animation, starring "Ricky Rat," the first 'toon to break into pictures with the help of "Dizzy Walters," and featuring a scandal surrounding a mysterious practice dubbed "the Ritual."

Shares