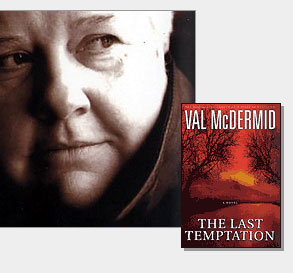

In the past decade or so British crime fiction has been fiercely determined to throw off its pervasive image (in this country at least) as the genre that specializes in tales of cozy little villages hiding dark secrets. The sleuths of yore, kindly old ladies or Scotland Yard inspectors whose crime-solving technique amounts to ruminative pipe smoking, have been replaced by harried cops and psychological profilers who are both more plausible and more rumpled (mentally as well as physically) than their fictional predecessors. The members of this new generation of British mystery authors (which includes a large Scottish contingent) function as reporters as much as novelists, mapping the structures and failures of Britain’s social institutions and the people who try to keep them working. The best writer, the most exciting and compassionate, to emerge from this school of British writing is the Scottish novelist Val McDermid.

Before writing mysteries McDermid spent 16 years as a reporter in the northern bureau of a national British newspaper. Her first mysteries were installments in two separate series featuring the detective Kate Brannigan and the journalist Lindsay Gordon. Then McDermid took a turn toward the darker side of crime fiction in 1995, when she published “The Mermaids Singing.” The first in her trilogy of books featuring Tony Hill, a psychological profiler (who may also be the first impotent detective hero in fiction), “Mermaids” capitalized on the new prominence of the serial killer in crime fiction, but it was a definite move away from the genre’s increasing fannish adulation of evil-genius killers.

The sequel, “The Wire in the Blood,” prompted the British crime fiction doyenne Ruth Rendell, herself no stranger to disturbing tales, to write, “It is so convincing that one fears reality may be like this and these events the awful truth.” Two stand-alones followed, “A Place of Execution,” a brilliant reversal of the village-with-a-secret English mystery and simply one of the greatest mystery novels ever written, and “Killing the Shadows,” in which thriller authors are murdered in ways copied from their books. McDermid’s latest book, “The Last Temptation,” the conclusion to the Tony Hill trilogy, features another serial killer, though that is only part of the story. Ranging across Europe, the book takes in the gunrunners and drug smugglers who have emerged from the collapse of the Cold War and touches on the abuses of the Stasi, the East German secret police. Salon spoke to McDermid during her stop in New York on her tour to promote “The Last Temptation.”

Were you always a crime-fiction reader?

Yeah, I’d always read a lot of crime fiction, and I always wanted to write. I always wanted to tell stories. The mystery seemed appealing because I knew the rules. You have to have a body, you have to have a detective, all that kind of stuff.

In what was being written in Britain at that time — I’m talking about the ’80s — you had two options: the police procedural and the village mystery. I did not know enough about the police to contemplate writing a police procedural. And, frankly, the cops I had met as a journalist had not filled me with a burning desire to spend more time in their company. So I felt that avenue was closed. The village mystery was really difficult for me to get my head around because I didn’t grow up in England. I grew up in a Scottish mining community. We did not have retired colonels of the Indian army. We didn’t even have vicars; we had ministers. So this world was completely alien to me. I felt that to write these kinda of books you had to have some kind of insider knowledge almost.

So I was playing with the idea, not really knowing what to do. And the catalyst for me was Sara Paretsky’s first novel, “Indemnity Only.” A friend who was living in the U.S. sent me a copy of it, and it was just a revelation. Here was someone writing about contemporary women’s lives that seemed to have a connection to the kind of lives that I saw around me. It had an urban setting and it had politics — politics in a personal sense and in a wider social sense. It was almost like reading Paretsky gave me permission to try to write the same style of book. I could write contemporary urban novels that had a sociopolitical dimension, which is what I’d always wanted to do. That was really what pushed me into actually starting it.

I don’t know if it still exists in the U.K., but in the U.S. there’s an idea that the English mystery is polite. It’s about the restoration of order, where the American mystery is hard-boiled and tough. Is that a perception that still dogs British mystery writers?

It’s a perception that is as false as the perception that American crime fiction is hard-boiled. You only have to go into any mystery bookstore to see the vast mountain of cozies that are produced by American writers. Whereas the best of British contemporary crime fiction is not like that at all, and I would include Ruth Rendell in that. She doesn’t write cozies. She writes hard-edged novels that are about British society.

It’s something that’s made it very difficult for my generation of British crime writers to break out in America, because we are fighting this expectation of what British crime fiction should be. The American market expects it to be cozy, expects it to be, as you say, about the restoration of order. And it’s been a little difficult for people to alter their understanding, to accept that British society isn’t like that anymore and that if they want to read books that reflect reality then they need to be reading people like Ian Rankin, Frances Fyfield, Denise Mina, Louise Welsh, because these are writers who are engaging with the contemporary world. Slowly but surely we are getting across that, yeah, we can write hard-edged noir novels that work in the context of our society, and the message is getting across to the discerning readers. It’s actually becoming a lot easier to convince people that, yes, we can write about the dark side of things, too.

In contemporary British crime fiction the heroes are often cops, and while they may have to fight dunderheads in their own ranks, in America the heroes still tend to be private eyes, renegades. Obviously there are exceptions on both sides. But does that imply that the British have greater faith in their institutions?

I don’t know if it’s so much that we’ve got greater faith in our institutions as that the private eye in the U.K. has always had a slightly different feel than in the U.S. In the U.S. the private eye has always had a kind of status, conferred by the fact that they have to be licensed, they have to qualify in certain respects to do their job. In the U.K. people have a much lower opinion of private eyes because anyone can be a P.I. You can get out of jail one day and set up your slate saying “I’m a private eye” the next day. You can be a convicted felon, you can be a con artist, and you can set yourself up as a private investigator. So I think we went from the amateur sleuths, which became increasingly difficult to sustain, to the idea that the people who actually solve crimes are the cops and the associated agencies, and the private eye doesn’t really figure in our mythology to the same extent.

Do you feel that crime writers are filling a void that literary fiction has left behind?

Yes, I think that’s very much the case. There’s been two things with literary fiction, I think. Literary fiction in the U.K. became very concerned with literary theory, critical theory, to the extent that the notion of narrative almost became a dirty word. That’s slowly started to change because the simple economics of the marketplace dictate that readers actually want to read things that have a beginning, a middle and an end. I think we’re hard-wired for narrative. I’ve been saying this until I’m blue in the face for the last 10 years. And interestingly enough there was an article recently in the Observer when the Booker short list came out saying precisely this, and I felt I’d been vindicated.

But it seems to me that although literary fiction is returning to the notion of narrative, [literary fiction writers] are still not engaging with the society that we’re living in. There’s a big boom in historical fiction, whether it’s recent history or further back in time. I mean Ian McEwan’s novel “Atonement” is essentially an historical novel. It doesn’t engage with the present day. And I think that if you look at the successful books in literary fiction, this is what you find. So the crime novel started to pick up the baton in the ’90s. We were the ones writing about the reality of the world we lived in.

One of the things that’s very strong in British crime fiction, in particular Scottish crime fiction, is the notion that the people who break the law are not the only criminals. Social institutions, the way we live, the structures we set up in our society, are often equally morally reprehensible. And I think a lot of British crime fiction deals with this notion that there’s more than one way to be criminal.

As a genre writer, do you feel like you’re fighting for respect?

I think most of us have given up the fight for respectability some time ago. I think we are content to be read, and we’re content to carry on trying to write the best books we can. It’s frustrating to see the way that we’re not regarded as being respectable. And I usually put this down to ignorance, people who don’t know better because they haven’t read anything since Agatha Christie. I remember the year that “A Place of Execution” came out in the U.K. the chair of the Booker judges was interviewed after the awards ceremony, and he was saying it had been a particularly strong year, it had been a hard choice, there had been a lot of contenders for the short list and the long list, including Val McDermid’s “A Place of Execution,” but of course that was a genre novel.

You just say: The readers like the books; that’s the important thing. And I know that as a writer I’m getting better, that I’m developing, that I’m a lot better writer than I was five years ago, two years ago, and every book is a process of trying to be better.

In his book “On Writing,” Stephen King said nobody ever asks genre writers about the language. They ask about the mechanics of plotting, but not about the care you take with the language.

Yeah.

That’s been your experience, I take it?

Yeah. I remember a few years ago at an arts festival, Ian Rankin and I were doing a panel with, as sometimes happens, the literary novelist who has attempted to dress himself in the clothing of the genre and purported to have subverted the genre. Which actually is another way of saying, writing a badly plotted crime novel. The moderator asked Ian about writing a police officer and how was that, and how did he do his research. He asked me what was so interesting about writing about psychological profiling.

And then he turned to the other writer and said, “Of course, you’re concerned with style and characterization.” Ian and I, our jaws just dropped. I sat and took this for about 20 minutes and I finally just blew. I couldn’t take any more of this insulting patronizing. I just went off, saying anyone who didn’t think that there was interesting experimental writing being done in the crime genre, and good writing being done in the crime genre, was displaying nothing more than the depth of their ignorance. I just went off on a roll and ranted for five minutes. I stopped, thinking there was going to be this deathly silence, I’m going to be drummed out of the festival. And the next thing I knew, the audience were stamping their feet and cheering. Go figure. They knew that they were reading good stuff.

We seem to be at a stage where we’re fetishizing the serial killer, with writers and filmmakers trying to outdo themselves with the most outrageous modus operandi they can come up with and the most gruesome murders. Sometimes there’s a barely disguised thrill in that writing. I don’t feel that in the Tony Hill trilogy or in “Killing the Shadows” — though there are things in your books that have made me blanch.

That’s a good thing, because if it didn’t, you should probably seek professional help.

What’s the line between desiring to thrill the reader and fetishizing or exploiting the violence?

You have to use your own judgment. That’s a tough line to walk. For me, what always holds me in check is that I try always to think about victims. The victims in my books are not just faceless ciphers who are there to be killed. They have, if you like, a life outside their death. That’s what I’ve always tried to keep in mind. And that’s what my investigators always hold in their heads. It’s not just a piece of meat. This is somebody who had life, who had loves, who had an existence, whose death sends ripples out that touch other people’s lives.

If you hold that in your head, it’s a way of keeping yourself from going onto the wrong side of the line. If you keep a concern with victims at the front of your head, then you don’t tip over into that area of the evil genius becoming the hero. And that’s what’s always contained me. But you do, at the end, have to use your own judgment. I hope that I stay on the right side of the line. One of the reasons I started writing these books is a disgust I felt at this very thing, the way that serial killing was almost turned into a kind of pornography. I would far rather disgust my readers than have them excited by that. I’m not in the business of cheap thrills. Very expensive thrills, yeah. [Laughs.] The reader has to pay for those thrills.

That’s one of things you’re parodying in “Killing the Shadows.”

Yeah, people die because they write badly. [Laughs.] I think that’s entirely reasonable, don’t you?

Is it hard to shut out the violence of your material sometimes?

I’ve never had any difficulty closing down at the end of the day. When you’re writing it, you’re always thinking about it as a piece of prose. Does this sentence work? Does this paragraph flow? Should I end the chapter here? You’re always being mediated by the technique. That stands between you and the text. The reader has a much different relationship with it, more intense. If I’ve done my job properly, it’s right there in the reader’s face. It’s other people’s work that gives me nightmares, not my own. When I read Denise Mina’s “Resolution,” my partner was shaking me at 4 o’clock in the morning because I was fast asleep shouting at the top of my voice, having some sort of nightmare. Which I don’t very often experience, but that did it for me. My nightmares don’t come from my own imagination but from other people’s. Because I have no control over that.

In a lot of crime fiction the detectives just seem lost in their emotional problems and the reader feels overwhelmed by the drabness and hopelessness of it all. Your characters, their problems notwithstanding, actually seem to enjoy their lives.

I wanted to reflect something a little different. I got very tired in the early ’90s, late ’80s with the succession of dysfunctional detectives. You think, these people can’t even organize their laundry. Why on earth would I expect them to be able to solve a crime?

I have to say my own experience of the world isn’t like this. The people I know who are really good at what they do tend to have lives that, in one way or another, are relatively comfortable. They live somewhere that has their mark; they come home to something. It may not be the person they love or their kids or whatever, but they come home to something that is not, you know, the grotty apartment with three weeks of pizza boxes on the floor. My characters have something to lose. They have something to drive them forward. You look at some of these [other] heroes and you think, why would you bother to do this stuff? Because you’ve got nothing invested in this except some quixotic notion of honor. I prefer to have characters who have more of an investment in the world they live in.

What writers were important to you and who do you read among your colleagues?

I think it would go back to who set me on the track to begin with, and obviously Paretsky, whom I mentioned. Ruth Rendell was a big influence on me, partly because she was one of the earliest crime writers who could write different styles and tones of book and get away with it, take your audience with you and still get published.

Robert Louis Stevenson was a huge influence on me in my childhood years. I can’t remember the number of times I’ve read “Treasure Island” and “Kidnapped,” and later on “Jekyll and Hyde.” I just loved the way he told stories, and I loved the darkness in his books. Which you didn’t get much of in children’s books at that time. The Scots are very good at darkness. We’re very good at dark nights of the soul, but we’re also very good at black humor. And you find aplenty in Stevenson. Writers I enjoy now: Denise Mina, Laurie King, Ian Rankin, James Lee Burke, Michael Connolly. Two first novels I enjoyed very much this year: a book called “The Waterclock,” by Jim Kelly, and also “The Cutting Room,” by Louise Welsh. There’s a lot of good writing going on in contemporary crime fiction. When we finish this interview, I’ll think of five other people I should mention.

Last question: Why are Scottish crime writers so tough?

[Affecting a brogue.] Y’ever been to Scotland by th’ way?

I think it comes down to what Hugh MacDiarmid defined as the Caledonian antisynergy, the pull of two polar opposites in the same people. We’re famously hospitable but we’re also famously xenophobic. We have this sort of dark Calvinist past and it’s still in place in the present. We also have this wonderful black sense of humor and we love to party. We’ve produced some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment, and also some of the worst slag-faced bigots in the history of human thought. So there’s always the dark pool of these opposites within us that produces a sort of dramatic tension.

And I think the reason why Scottish crime fiction has emerged so much in recent years is that for the first time in 300 years we’ve been forced to operate as a nation again. We have a parliament. We have to think of how we define ourselves. For 300 years we’ve been defining ourselves as “We hate the English and we’re not them.” Now we have to start thinking more positively of our own case. What does that make us? Who we are? And this happened at a time when British crime fiction started to be written with a much wider social perspective. We are the dark knight of the soul.