Michael Jackson's nose. Pamela Anderson's boobs. Barbara Hershey's lips. Cher's everything. We expect our celebrities to go under the knife in pursuit of perfection. From the "Did she or didn't she?" perma-youth of stars like Goldie Hawn, Demi Moore and Madonna to the tragic joke that is the former King of Pop, the general message hasn't much changed: If it ain't broke, fix it anyway.

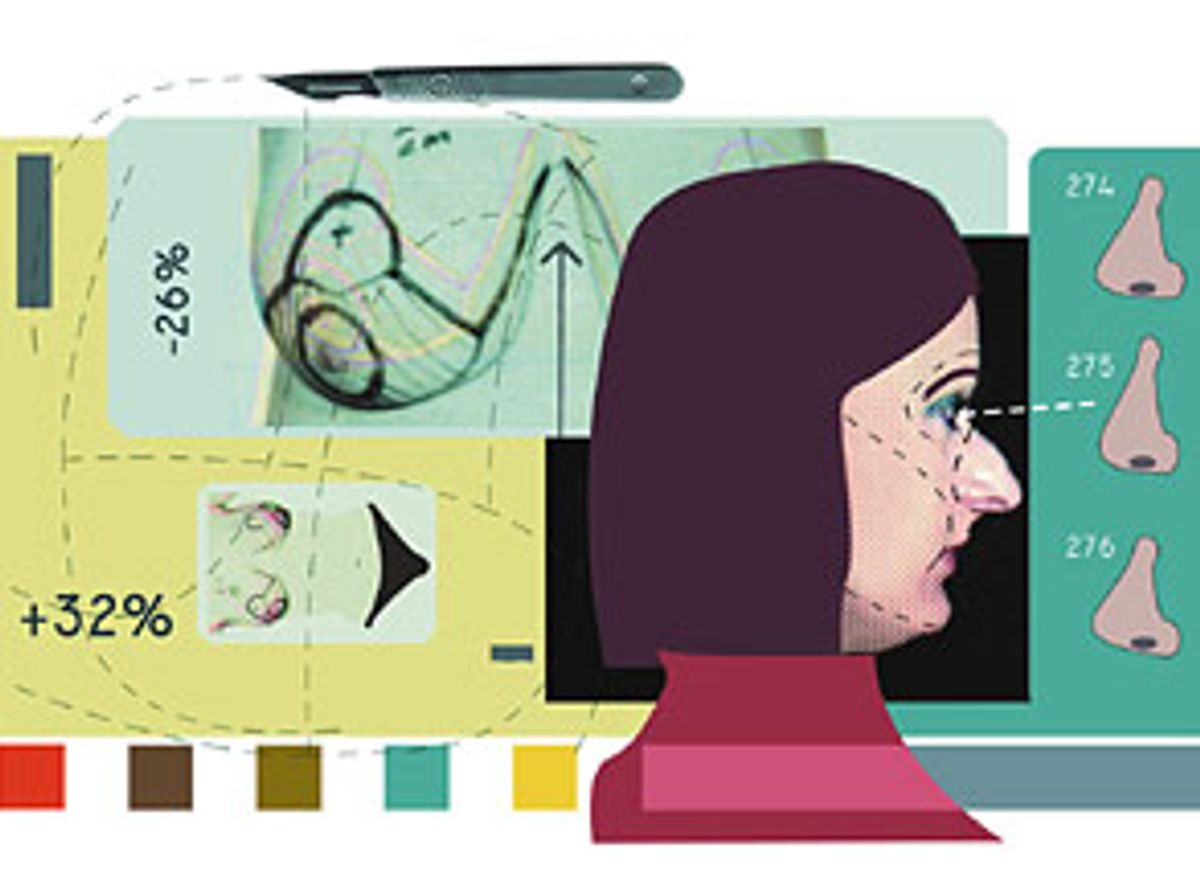

But plastic surgery is not just for the rich and shallow; it's gone mainstream. As medical breakthroughs make procedures more affordable, and the constant media images of beauty make it ever more desirable, carving and stretching new faces and bodies may be one of the only boom businesses left. In 2001 more than 7.5 million Americans underwent cosmetic surgery -- and about 15 percent of them were men.

The latest sign of plastic surgery's intriguing power is that it debuted in its own reality show -- last week's "Extreme Makeover" on ABC. In it, three imperfect but rather attractive Americans underwent more procedures than they'd originally intended -- and whether they looked better afterward is a question of taste.

But at what point does a national preoccupation with appearance cross over into pathology? Should Americans be spending less time at the surgeon's and more time on the psychiatrist's couch?

Dr. Katharine Phillips is a professor at Brown University, the director of the Body Image Program at Butler Hospital in Providence, R.I., and the author of "The Broken Mirror: Understanding and Treating Body Dysmorphic Disorder," the first major study of the illness.

According to Phillips, between 1 and 2 percent of all Americans suffer from body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) -- the debilitating belief that something is severely wrong with one's body. People affected with BDD can be so certain of their own ugliness that they cut themselves off from friends and loved ones. They can become depressed, even suicidal. They may turn repeatedly to plastic surgery but are never satisfied with the outcome.

Recently, Phillips took time out from a conference in Puerto Rico to speak with Salon about Michael Jackson, the limits of plastic surgery, and how to tell the difference between a healthy desire to look good and an unhealthy obsession with physical imperfections that may not even exist.

Is is really accurate to characterize a certain obsession with appearance as an illness? Or is it more an issue of vanity gone awry?

No, it's not simple vanity. Most of the people with BDD I have seen do not want to look beautiful and don't necessarily want to be noticed for their appearance. In fact, the opposite is true; they just want to look normal -- and think they don't.

So some patients will say, "I look like the Elephant Man," and they'll really believe it. They don't necessarily want to look like Ben Affleck. They want to blend into the crowd.

For example, a young girl I'm seeing now -- she should be in the tenth grade -- is lovely. But she's obsessed that her face is really scarred. It's not. But she thinks it is. And she's housebound! She has very minor acne, very minimal, nothing you would ever notice when you first look at it. She has to point it out to you. And she hasn't gone to school since she was in the eighth grade because she thinks she's so ugly and she doesn't want anyone to see her. This is not normal vanity.

What kinds of steps do people with BDD take?

A lot of them get surgery, or go to dermatologists, which seems not to help as far as I can tell. We definitely need more research on this. We find that people tend not to be happy with the outcome. Even if it's objectively acceptable, they tend not to like it. They think the surgeons didn't do exactly what they wanted or they still don't look right, and they shift to another body area.

One patient will say, "My nose looks a little better but now my stomach has taken over for my nose." Because really, fundamentally, the problem in BDD involves distorted body image and a tendency to obsess and worry. So if you change a surface characteristic, it's not going to change the underlying tendencies people with BDD have. So they tend not to be happy with the results. Even if they think they look better, they obsess anyway because they're worried it's going to get worse again. Surgery and dermatologic procedures tend not to be the solution.

I think one of the reasons people with BDD suffer so terribly is because they end up so isolated. Think about it. If you really thought you looked like the Elephant Man or the wife of Frankenstein, as one patient said to me, or the "third ugliest person in the world," as another patient said to me, think about how that would affect you. Would you go to a party tonight? No. Would you ask someone out on a date? No.

This brings Michael Jackson to mind. He's isolated and is constantly under the knife. Does he have BDD?

I can't comment on public figures unless they've admitted to having BDD, so I can't comment on him specifically. But what I can say is that one of the clues is that people are having a lot of plastic surgery and are unhappy with the outcome. That may indicate that BDD is present. It doesn't necessarily mean they have BDD, but it may.

What would your response be to those who are still skeptical that this disorder exists, that it's just another example of the new "syndrome society"?

People were very skeptical when I first started studying this as a resident more than 10 years ago. I heard things like, "Oh, you're making it up" or "Don't waste your time." I think most of that skepticism has vanished. I think that the research shows that it's a real disorder. There are patients who are really out there and who are really suffering.

As for the skeptics today, what would I say? I'd say go out and treat some patients. Please. This is not just theory. We're talking about real people with real lives. Talk to three people with BDD, talk to 300 with BDD. Try to treat them. Lose a patient to suicide.

This is a really serious psychiatric illness. Maybe it's related to depression; maybe it's related to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). These are unanswered questions. To trivialize it, and to trivialize the suffering of these people, is really unfortunate.

What is the connection between BDD and OCD?

They have a number of similarities. People with BDD, like people with OCD, tend to obsess. They have a thought that they can't get out of their mind, and they keep worrying about it. You tell them to stop worrying and they can't, and they have to keep doing these repetitive behaviors to try to feel better. So the person with OCD will keep washing his hands and the person with BDD will keep checking the mirror because they're both trying to feel better and stop the obsession, which doesn't work.

Both groups seem to respond to similar treatments, although we have to learn more about how to treat BDD. I think that we'll find that the treatments do differ a little bit from each other. But the basic general approaches to treatment are quite similar.

There are also quite a number of important differences that patients and doctors and families of people with BDD should be aware of. One is that people with BDD tend to be more depressed, and so they can be more suicidal and more miserable, more unhappy. It's not to say that people with OCD aren't, but on average people with BDD tend to be more depressed.

They also are much more socially anxious. They are very worried that other people are going to think they're ugly. They feel anxious around other people. They may think people are staring at them, or laughing at them, or making fun of them, so there's a lot of social anxiety and avoidance. That's generally not the case for OCD. OCD is not so interpersonal, not so socially based.

When a patient comes to see you, is she or he aware that there's something wrong?

That's another difference between BDD and OCD that's worth highlighting. Most people with BDD think that their distorted view is accurate. They think they are right and you are wrong. Most people with OCD recognize that their belief isn't accurate but they can't help worrying anyway. That's a pretty big difference between them.

People with BDD see surgeons because they really do believe they look ugly and deformed, and when you try to tell them, "You look fine," and "Don't worry, you look great," or at least, "You don't look abnormal," they think you're lying, or you're just being nice, or you need a new pair of glasses. It's really important to recognize that you can't just talk these people out of their body-image concerns. Simple reassurance alone doesn't work.

What have you found about the differences between men and women with BDD?

They're pretty similar. Men are more likely to have muscle dysmorphia -- which is a form of BDD in which men much more often than women think they're too small and puny-looking and they take anabolic steroids and work out obsessively. But the disorder itself generally seems pretty evenly split between the two genders.

Do you see the disorder as a modern disease?

No, it's been around for a really long time. In fact, [Italian psychiatrist Enrique] Morselli, who first wrote about the disorder more than 100 years ago, referred to prior descriptions of this. He writes about it as if it's a well-known syndrome. This is not a product of Madison Avenue advertising or modern L.A. culture. These things don't help, but there's more going on.

What about the prevalence of plastic surgery in our society?

Is getting plastic surgery a good thing? That's a very personal decision but I don't think people can say necessarily that it's a bad thing. Some cultures are much more focused on appearance than others. From a personal perspective, I think that there are other aspects to people that are more important than appearance. But it's a matter of values.

But that's not necessarily BDD. The illness is quite different in the sense that people aren't pursuing attractiveness in a healthy kind of way. They are obsessed with the idea that they look deformed.

What kinds of ethical standards should surgeons be held to when they're dealing with a patient who may be suffering from BDD?

That's a much broader question that I can't really answer. I'm not in a position to say what plastic surgeons should and shouldn't be doing. I think that they need to be more aware of BDD, and they should think carefully about whether they want to operate or not, because it seems as if these patients usually are not happy with the outcome.

The main thing is that we need more research to help the plastic surgeons identify these patients. In the meantime, plastic surgeons should ask questions to try to figure out whether the patient has BDD, like "How much time do you spend worrying about this problem?" and "How does it affect your life" and "How much does it upset you?"

If the patient is obsessing about a relatively minor defect for at least an hour a day, and if it's causing a fair amount of real distress and interference in his or her life, and certainly if it's causing him or her to be suicidal or depressed, then BDD is a real probability. One thing we do know is that these patients do well with psychiatric treatment, not with surgery.

What triggers the disorder?

We're just getting clues about that. It's probably very complicated and probably a mix of genetic biological vulnerability and life experiences. The brain chemical serotonin is probably involved, because medications that correct serotonin balance in the brain often help.

Life experiences may play a role for some people. For example, if you were teased a lot about your appearance as a kid, and you're biologically predisposed toward BDD, together that [may lead to] BDD. But it's not going to have the same cause in each person.

I think also our culture, which puts an emphasis on appearance, probably plays a role -- a bigger role for some people than for others.

It may have an evolutionary root in part. For example, in the animal world, symmetry is more important. Moths with more symmetrical wings get more mates. Symmetry signifies reproductive health.

I think probably all of these factors play some role in the cause. BDD is not going to be explained by any one of these alone.

Let's say I'm a mother. My teenage daughter always thinks she's ugly. She wants a nose job, and she wants her breasts enlarged. At what point do I start worrying about her?

Basically, you need to ascertain that your daughter really thinks there's something wrong with how she looks -- not that she thinks she looks fine but could look better, but that she really believes she has a deformity or an abnormality. Wanting to look good is not BDD, it's human. In fact, if you don't pay any attention to how you look, that's probably abnormal and unhealthy. A certain amount of paying attention to your body and grooming is very normal.

But if you're worrying about it constantly -- I don't mean worrying for just 15 minutes a day -- it could be a problem. People with BDD obsess about this for hours a day -- at least for an hour, but often more like three to eight hours a day.

For teenagers, or anyone for that matter, some of the questions you need to ask yourself are: Am I really preoccupied with flaws in my appearance that other people consider nonexistent or minimal? Do I think about this for an hour or more per day? How much distress does it cause? And does it interfere with my functioning?

In some ways, distress and function are the bottom line. If you are getting depressed over worries about your appearance, if you don't have a normal social life, if it starts affecting your work, your family, your functioning, that's probably a big clue that your concerns are no longer in the healthy normal realm and you may have BDD.

Shares