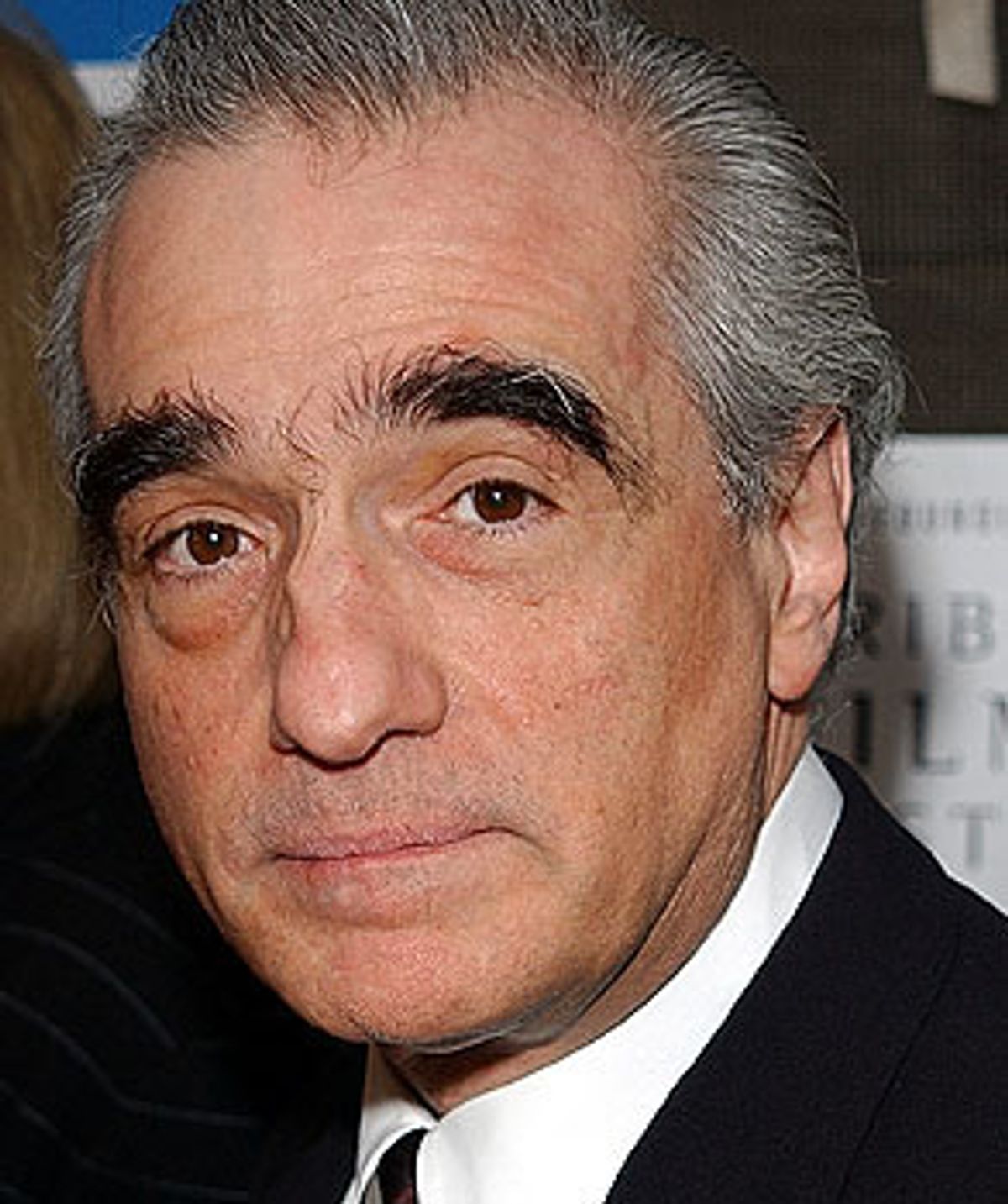

Who is the most important American filmmaker of the last 30 years? Strangely, you will encounter very little debate among movie critics and fans on this question. Since seizing the mainstream film world's attention with "Mean Streets" in 1973 (he had actually made several previous movies) and the bloody-minded, nightmarish and hauntingly beautiful "Taxi Driver" three years later, Martin Scorsese has been in a class of his own.

From "Raging Bull" to "The King of Comedy" to "The Last Temptation of Christ" to "Goodfellas," Scorsese's work has seemed to blend the grandest traditions of Hollywood with the rebellious spirit and artistic ambition of the young directors of the 1970s. Scorsese's work is informed both by the big, showboating spectacles he saw in his New York childhood during the 1940s and '50s and by the personal, intimate films of Italian neorealism and the French New Wave. His films are subjective, dynamic and individual, but his social canvas is always large and his appreciation of the social, cultural and political forces that come to bear on individual human life is both generous and sophisticated.

In the 1990s, Scorsese's films became even more diverse in focus and, at least arguably, were underappreciated as a result. In "Casino" (1995) he returned to a now-familiar realm of brash, even vulgar American violence and glamour, of the Mob and its mythologies. Perhaps he was bidding farewell to all that. "Casino" was sandwiched by journeys into unfamiliar territory: to the arcane social rituals of upper-class, turn-of-the-century Manhattan in "The Age of Innocence" (1993) and to Tibet, to tell the story of the Dalai Lama's childhood and the conquest of his nation, in the astonishing "Kundun" (1997). These may be among the best films of his entire career, but perhaps the lack of gunplay and retro-chic sets and costumes kept the multiplex crowds away.

After the commercial disappointment of "Bringing Out the Dead" in 1999 -- its vision of a drug-crazed, decaying 1980s New York perhaps at odds with the squeaky-clean image of the Rudy Giuliani era -- Scorsese turned to a massive project he had been considering for decades. "Gangs of New York," a sprawling, operatic saga of the street clashes between "nativist" Anglo-Americans and Irish immigrants that culminated in the horrific anti-draft riots of 1863, is that project. Since the Manhattan of 140 years ago has for all practical purposes disappeared under subsequent construction, Scorsese built an enormous New York set at the Cinecittà studios outside Rome for what became one of the most ambitious motion pictures of recent decades.

Starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Daniel Day-Lewis as leaders of the rival street factions, "Gangs of New York" opens Dec. 20. Even in a holiday season that features a new installment in the "Lord of the Rings" franchise (opening Dec. 18) and a Steven Spielberg '60s romp ("Catch Me If You Can," also starring DiCaprio, which opens Dec. 25), "Gangs of New York" comes with more artistic mojo attached, and higher stakes, than any other Hollywood movie of the year.

On Nov. 9, at the American Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, N.Y., Scorsese sat down with New York Times critic Janet Maslin for an interview and moderated discussion about "Gangs of New York," how and why he lost a 1990 Academy Award to Kevin Costner, the new generation of American filmmakers, his childhood in Manhattan's Little Italy and "The Sopranos." The event was presented as part of Pinewood Dialogues, the museum's ongoing interview series, in conjunction with the retrospective Martin Scorsese Directs. Here, Salon presents excerpts from the interview, edited slightly for length and clarity. You can find the full text and audio versions, along with many other filmmaker interviews and a wealth of related material, at the AMMI's Pinewood Dialogues Online Web site.

-- Andrew O'Hehir

Janet Maslin: You've been talking about "Gangs of New York" for 30 years.

Thirty years, yeah. Well, some of the things take a long time. "Last Temptation" was 15 years. "Mean Streets" was my whole life up to that point, you know.

Can you explain why it's taken 30 years to do this?

Having read the Herbert Asbury book, "Gangs of New York," back in 1970. It's a nonfiction book, but it also takes in the mythology of New York. And it goes back to a time of extraordinarily flamboyant folk tales of New York that go from the 18th century up to the 1920s. He wrote the book in 1926.

You read it when you were in your 20s, you were staying at somebody's house.

Yeah, a friend of mine was house-sitting for somebody out on Long Island. It was New Year's Eve and then New Year's Day. It was snowing outside, we were just by the fire, and I found these books. So this one said "Gangs of New York," and I took it out and started reading. They were reading "Time and Again," which had just been published. But I was reading "Gangs." When I told that to Harvey Weinstein, he said, "That tells the whole story." He's another one; he had heard me telling the stories for years and ... it's really about old New York. I mean, that's one of the problems. One of the problems [with making the film] was that none of the old New York exists.

So you had to build your own New York City.

We had to build it, yeah.

When you first thought of doing this all that time ago, you weren't in a position to build New York City.

No.

So did you imagine a smaller version?

No, bigger. Even bigger, even bigger. But also the fact that I had to tell so much of the story of the old New York, you know? Really, I didn't know where to stop it.

So you really never thought about camouflaging existing buildings, the existing city?

There's no way. I think it would not be financially feasible to camouflage New York the way it is now.

So years go by, you build New York in Rome.

Yeah.

Apparently, you've reshot some of the film and changed the music?

No, no, we're just really completing the music. I do a lot with source music, you know.

Did you reshoot the ending?

Not really. I shot some close-ups, which is what I did on "Cape Fear" and "Casino." "Casino," we reshot one scene and shot another scene to compress time. Usually in the editing, I find that at a certain point I'll be able to tell if I need some connective tissue, so to speak, and one more little plot device to carry through.

On "After Hours," I wound up shooting four days, to combine a lot of story points. Well, the original cut was two-and-a-half hours. And the whole idea was just like a Chinese box, you know, you open it up and you just keep opening, there's another box, there's another box, another box. And eventually, we decided we had to maybe compress about 10 or 12 of those boxes by shooting a new scene, and shooting some other elements. And combined it all. And so we reshot four days, and also a different ending, actually, on that.

All you need to know about the Oscars, I think, is that you lost to Kevin Costner [in the 1990 best director category, when Scorsese was nominated for "Goodfellas"].

For directing "Dances With Wolves," yeah. Well, the picture I can understand, because, the thing is that, you know, the Academy is an institution. As one of the key figures at one point told me, "We vote for the film that should win." Meaning at times, they may not necessarily look at the art or the craft, but at the ... This has happened over the years. With "Mrs. Miniver" [in 1942] -- William Wyler's a great director, but I prefer some of his other pictures. Or "How Green Was My Valley" [in 1941]. John Ford's a great director, but over "Citizen Kane," no.

Well, Orson Welles didn't have Miramax campaigning for him.

I guess not, I guess not. Oh, Harvey and the guys there, they're going out there beating the drums, I guess. But the thing about it, too, is that what I realized, you have to sort of get philosophical about it. I got to make these pictures, and the pictures were pretty tough. I mean, "Taxi Driver" was a labor of love. I didn't even think anybody was going to go see it. And it turned out that it became very popular.

[To audience.] Has anyone seen Travis Bickle's Mohawk in the exhibit upstairs? Honestly, if you go upstairs, the Mohawk wig is under glass.

[Robert DeNiro] couldn't cut his hair because we were shooting so fast and he had to go on to do "The Last Tycoon." So we had to make a wig. "Goodfellas" was also an edgy film. They were kind of nasty, in a way, the pictures. I think it was amazing I got away [with] making them, under the system at the studio, under the MPAA, all of that. So we sort of took what we could get and ran -- and that was to make the movies.

"Raging Bull" was another one ... when I made that, I thought: This was it. I kind of put everything I knew into pictures, and then I was going to start on something new. I thought I was going to go off and do documentaries in Rome for [the British independent network] ITV. Really, I was looking forward to it. The church, religious stories, and that sort of thing. Well, because RAI [Italian state television] at the time -- Rossellini had done films, but also Olmi was doing a lot and Bertolucci had done a few. I thought that was the way to go -- for me, anyway.

Well, "Gangs of New York," I mean, the part I've seen looks fabulous, but it's no day at the beach, I don't think.

No, it is no day at the beach. No.

It's a very violent story.

I mean, the thing is, they kept saying, "Oh, Marty, this is violent." I said, "Yeah." "Well, how do you shoot it then?" I mean, "Mean Streets" is rough and then "Taxi Driver" certainly has a lot of violence at the end and "Raging Bull" has violence. But it's more the emotional violence, which comes by way of being fed, nurtured on the films of Sam Fuller and how he was expressing emotional violence with camera movement and editing.

But this is filled with violence about different groups jockeying for position in New York?

Hitting each other. Yes. Hitting. OK.

Do you have the 1863 draft riots in the film?

Yes, we do, towards the end. The draft riots are the backdrop.

They'll love that in the Academy.

But the draft riots are the backdrop. The reality is that the violence is handled in such a way that I had to sort of say, "Well, you know, what am I gonna do?" I've mentioned this before, where I said when I got to do "Casino," and it got to the point where Joe Pesci and his brother were killed with baseball bats in a cornfield, I did it very straight. It was the last statement I think I could make on that kind of violence. Especially these two guys, whether you like them or not, as charming as they could be, they were pretty bad gangsters. But being killed in such a brutal way by their friends, this is the end of the lifestyle, this is the end of the rainbow, guys. So that was the last statement for me on that kind of thing. After that, violence has to be treated in a different way. What I tried to do in this picture is, through the editing, suggest the impact rather than see it. So it's really more montage than direct violence.

Is it partly a result of the stage of life you're at? The fact that you made a lot of young man's films that were very violent, and that were about outsiders wanting to belong, and about feelings that you might not have anymore?

No, I'm still an outsider wanting to belong!

Some outsider!

No, no, no. There's a psychological thing that you realize: Why do you want to belong? Just do your thing and that's all, the hell with it. Really, I mean, that's part of it with the Academy, too, to a certain extent. It's like being an outsider, and just dealing with that. There's a part of me, having grown up seeing the Academy Awards on TV; there's a certain kind of acceptance. Your parents react to it and that sort of thing.

But if it ain't in the cards ... The main thing is to just get the films made, and to try to combine the kind of film I want to make with what I hope could be interesting at the box office.

[Question from the audience]: Considering that film today is more and more considered as a product and less and less as an art form, what would you say to young film directors who feel they have to use their personal voice, and that it's a struggle to make film as an art, but feel that it's the sacrifice they have to make?

That's always been my dilemma myself -- even in "Gangs," for example, or "The Age of Innocence," or any of these pictures that I've made, really. How far can we deal with the box office and what the box-office demands are? Because they are giving you a lot of money, which means you're responsible for it, and you're obligated to do certain things. Can you tell the same story? Or can you find yourself, like, a kind of personal way into these stories, and make your own personal statement? Which means, can you feel strongly passionate enough about something that can, through the nature of the way it's made, the look of it, particularly the casting, be bankable at the box office? I don't think, especially in the culture the way it is now, I don't think that's going to get any easier. It's only going to get harder.

And I think that for younger people, there's a lot of wonderful role models you could take who are making independent cinema, and not dealing with the mass box office, you know. I think some are coming around: Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson. There's so many of these younger guys -- men and women -- working, who seem to be crossing over into marketable cinema, by which I mean bigger budgets.

Maslin: What has to happen to "Gangs of New York" for it to be marketable?

You know, I don't know; I never understood enough about the money. I just know that this was a tough one to make. We all made sacrifices. I put most of my salary in the picture, for the first time in my life. I believed in it that way.

[Question from the audience]: What do you think about your films' influence on America's fascination with the gangster, and the popularity of television shows like "The Sopranos"?

Well, the fascination with the gangster is interesting. I have to tell you, when I was growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, I was part of a world that had that as an element.

Maslin: I think you once said, "If I can buy toothpaste for 19 cents from a fellow on a truck, instead of buying it for 50 cents ..."

Oh, yeah. That was the thing. Hey, you know, sometimes my mother would ask, "Hey, what fell off the truck today?" Not that she's a thief, but you buy it. "Yellow sweaters! Hey, look what the guys got off the truck," you know, and you bring it around. You gotta beat the system somehow. They were not educated. A lot of the Sicilians, the Italian-Americans, were very, very suspicious about government and church. That's one of the reasons they ran away from Sicily. They certainly weren't going to, you know, put themselves in the hands of an American police force. You have to understand the cultural issues there. They wouldn't trust it. Just basically stayed with the family and everything else. And so for the first, and into the second generation, I think, it was difficult to get them to understand about taking advantage of America, the opportunity for education, which gives you power, makes you move and that sort of thing.

I never thought the things that I put on film could've been put on film when I was growing up. Despite the fact that you had the majority of the people down there [in Manhattan's Little Italy, where Scorsese grew up] being hardworking, working-class families, going to the garment district and coming back, you know. They were not underworld characters, the majority were really good, decent people. But it's that odd combination of knowing people and liking them, and then finding out later what they did. Or knowing some people and not liking them, and finding out what it was they did.

You never brought a camera into where I grew up; you weren't allowed to bring a camera. A motion picture camera, forget it. That would be outrageous. And then for "Who's That Knocking at My Door?" [1968], I was able to shoot [in the neighborhood] a little bit, and in "Mean Streets" very, very little; but my father had to talk to certain people to make sure.

But right after that, right around the time I helped Dean Tavoularis look for locations for "The Godfather" in my neighborhood, it started to pay off then, you see. They went into a couple of places in the Lower East Side, they paid the olive oil factory we found. St. Patrick's old cathedral, they shot the interior of the baptism of "The Godfather" in there. After that, the church had a little money and they fixed it up and that sort of thing. So it started to become: "Hey, we could be friendly to the outside world." They could let us in. I think "The Godfather" changed that, to a certain extent. But "The Godfather" deals with a very patrician level of the underworld, in a way.

Could you have ever imagined this turning into America's favorite television character?

No, no. No, that I can't imagine.

Have you ever watched "The Sopranos"?

No, not really. I saw one show a long time ago. I liked it. The actors are good and everything. Some of the actors I've worked with, they're really great. A number of friends of mine are real fans of it.

That period, by the way ... The films I made, "Mean Streets" and "Goodfellas" and even elements of "Raging Bull" -- because the whole thing is not about the underworld -- they're of a time and place, the 1940s and 1950s, early 1960s. I mean, "Mean Streets" is really about 1960 to '63. I shot it in the '70s, but it really is earlier. Like the girl groups, Phil Spector. It really was that sound right before the Beatles hit. And that way of life doesn't exist anymore anywhere.

I think "The Sopranos" is interesting, because it's modern, isn't it? It's a modern thing. New Jersey and they've got long hair and stuff. I mean, you know, it was a different thing. I'm used to the camel-hair coats and that sort of thing. I don't think I could ever do a film about that world now, what it's become.

Shares