The operative word in any year-end best list should be "best." And in any year, that can't be limited to an arbitrary number. Ten may be standard, but it's meaningless in discerning the quality of the year in movies. Some years there are barely 10 films to fill out a list, and in the dismal spring and early summer of 2002 it looked as if it was going to be that kind of a year. But with no explanation that I can think of, it has actually turned out to be a pretty good year for movies.

As always, good movies continue -- somehow -- to get made. The bad news is that they don't get seen. Audiences didn't turn out for two of the most daring and original American movies of the year, "Femme Fatale" and "Punch-Drunk Love." A good movie not on my list, Steven Soderbergh's rigorous, risky and relentlessly personal "Solaris" -- a disturbing meditation on memory as emotional fascism -- is dying in theaters. Two charming entertainments, "Possession" and "CQ," were sabotaged by knuckleheaded reviews. The shaky state of foreign film distribution meant that the highly praised Taiwanese movie "What Time Is It There?" was gone from theaters in two weeks.

Paramount Classics did everything it could to sabotage Clare Peploe's blissful film of the Marivaux play "Triumph of Love." And as I write this, Lynne Ramsay's beautiful and utterly original "Morvern Callar" is about to open in New York with hardly any advance publicity. (The people I've alerted to it haven't even heard of it.) This is not an atmosphere in which advocacy should be parsimonious. So, sick of culling things down and leaving off worthy movies that any 10-best list entails, I offer up this list of the 16 movies that deserve to be called this year's best.

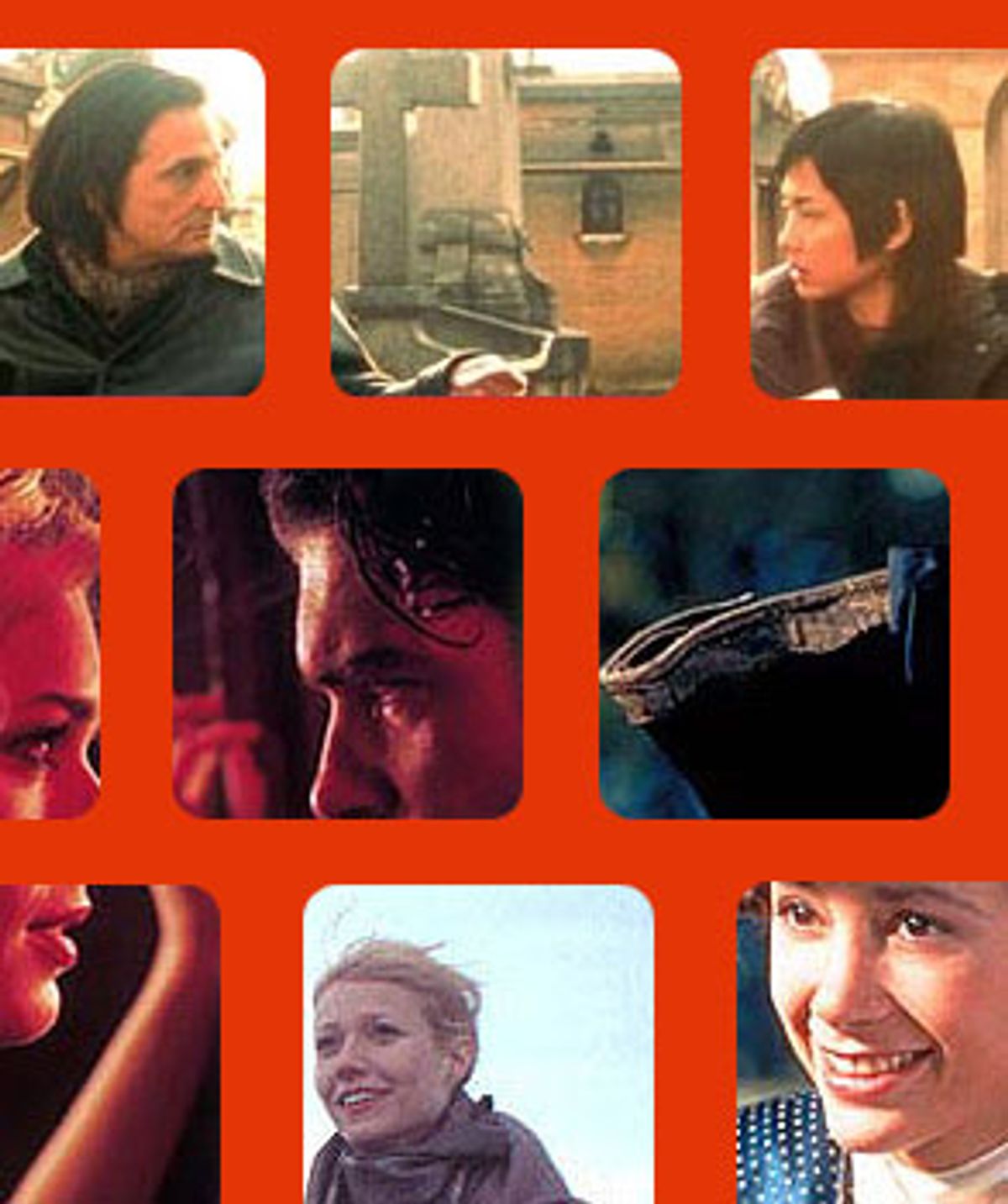

1) "Y Tu Mamá También" Alfonso Cuarón's road movie is one of the handful of great erotic films ever, and the fact that it turned out to be successful was among the most heartening of the year's developments. If freedom in the movies is the refusal to fear risk, then Cuarón has made one of the freest movies of all time, and certainly one of the most joyous. Primal forces who haven't surrendered to respectability, the movie's two sweet-tempered horny heroes, played by Diego Luna and Gael García Bernal, walk around in a pot haze with rockets in their pockets. And as the "older" woman they take on their road trip, Maribel Verdú is the movie's carnal Madonna.

2) "What Time Is It There?" Magic. This film from the Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-Liang has been described by the critic Howard Hampton as Buster Keaton inhabiting the soul of Antonioni. Tsai's perpetual lead, Lee Keng-Sheng, plays a street vendor who sells a watch to a Taiwanese girl (the ineffable Chen Shiang-Chyi) heading off to Paris. Filled with longing, he spends the rest of the movie setting all the clocks in Taipei to Paris time. A boy-never-meets-girl story that cuts between two continents, "What Time Is It There?" is a deadpan, nearly silent comedy about the connections between people who remain separate. And, as in the great silent comedies, the jokes coalesce out of the mundane. What makes Tsai's film so moving is the director's determination to find poetry in an urban world that has seemingly banished it.

3) "Femme Fatale" As a visual storyteller Brian De Palma is without equal in contemporary moviemaking. Inevitably, his films are dismissed by critics and audiences who have become too lazy to process visual information. (Here's a decoder: When a critic describes a De Palma film as "incoherent" it usually means he was too lazy to follow it.) Like a plush seat at the swankiest peep show in town, "Femme Fatale" allows us to luxuriate in De Palma's chic, sleek erotic trickery. He signals us to every trick he is playing on us and, because movies are about wanting to be fooled, we are only too happy to be taken in. De Palma has always loathed the sentimental manipulations of movies, and in "Femme Fatale" he turns the misogyny of film noir on its head, giving us a corrupt heroine and making us acknowledge that we love her for being so bad. As De Palma's heroine, Rebecca Romijn-Stamos gives a sexy, gleeful performance that leaves the sexual timidity of more established actresses in the dust. No movie this year offered the sensual pleasure that this sex-fantasy thriller did. No American movie was better.

4) "Morvern Callar" The combination of kitchen-sink realism and visionary poetry that failed to coalesce in Scottish director Lynne Ramsay's acclaimed debut "Ratcatcher" takes flight in this adaptation of Alan Warner's seemingly unadaptable novel. Samantha Morton, playing a supermarket clerk living in a bleak Scottish port, continues as the most astonishing actress working in movies. The suicide of her boyfriend on Christmas day turns out to be the potential key to her freedom. Descending into the derangement of grief but suspending any moral judgment in order to immerse us in her heroine's psyche, Ramsay moves the picture to the shifting rhythms of somber, luxuriant solitude and freedom that is no less compelling because it holds a knife's edge of danger. "Morvern Callar" works on you like a drug, its mood still transfixing you long after you leave the theater.

5) "Far From Heaven" Todd Haynes' homage to the '50s melodramas of Douglas Sirk is far from an Imitation of Strife. Supple where Sirk's films are brittle, flowing where Sirk is schematic, Haynes' suburban melodrama avoids every trap of archness and camp. By the end the film has turned into a kiss goodbye for the entire genre. To imagine any future life for the film's three protagonists, played by Julianne Moore, Dennis Quaid and Dennis Haysbert, you have to imagine not just why American society at the end of the '50s had to change, but why American movies did, too.

6) "The Pianist" In telling the story of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a Jewish Polish classical pianist (the amazing Adrien Brody) who spent World War II hiding out in the Warsaw ghetto, Roman Polanski, who spent his World War II boyhood hiding in the Krakow ghetto, has tackled the roots of the themes of violence and victimization that run through his movies. Almost unbearable to watch at times, the film in the second half becomes something like a silent comedy about the Holocaust. The few laughs are black but, as in Buster Keaton's greatest films, "The Pianist" confronts the bottomless melancholy of the imperative to survive in a hostile universe. The Chopin that courses through the film -- as well as the finest filmmaking of Polanski's career -- makes the case for art as a way back to our finer selves in a violent world.

7) "Chicago" A great American movie musical, and when was the last time you could say that? Bob Fosse's original Broadway production implicated the audience for their willingness to be blinded by celebrity. In this film, based on the current Broadway revival, choreographer Rob Marshall, making a stunning directing debut, shuns Fosse's moralism for the exhilarating amorality that has long characterized the best American entertainments. Fast, funny, cynical, resolutely unsentimental and anti-romantic in the tradition of shows like "Pal Joey" and "Guys and Dolls," "Chicago" moves along on one of the great musical scores (by John Kander and Fred Ebb) and on the energy that makes it a nonstop thrill to watch. The movie revels in showbiz razzle, and this cast -- Catherine Zeta-Jones, Renée Zellweger, Richard Gere, Queen Latifah, John C. Reilly -- can really dazzle.

8) "Triumph of Love" Thrown into theaters by Paramount Classics and almost unseen, Clare Peploe's film of the 18th century Marivaux comedy is bliss. A graceful example of how theater can be transferred to the screen, Peploe's film has the beribboned utopian delicacy of a Fragonard painting. And as acted by Mira Sorvino, Ben Kingsley and the wonderful Fiona Shaw, it has the depth of romantic feeling that farce can give.

9) "CQ" It received the nastiest, most uncomprehending reviews of the year, but I don't know how anyone who claims to love movies could fail to be charmed by Roman Coppola's valentine to '60s cinema. Not just the small, personal art-house movies that the filmmaker hero (Jeremy Davies) is making, but the loopy Euro sci-fi epic (based on Mario Bava's "Danger: Diabolik") he's working on. In the embrace of Coppola's movie love, there is no artificial barrier between mainstream and art filmmaking: They are both places where Davies is able to find his voice. With terrific comic turns by Giancarlo Giannini, Gérard Depardieu, Jason Schwartzman and Billy Zane, and a charming performance by model Angela Lindvall as an American Alice in the wonderland of 1968 Paris.

10) "Possession" Was Neil LaBute's film of the A.S. Byatt novel punished because LaBute dared to reveal his romantic side? His usual partisans greeted this film as though it were indistinguishable from the average Merchant-Ivory snoozer. But in some ways, LaBute understands Byatt's novel better than the author herself. Minus the literary ventriloquism that bogged down the book, it's about people who use intellectualism as a defense mechanism. The movie's joke, and it's a good one, is that the film's Victorian lovers (Jeremy Northam and Jennifer Ehle) are more able to surrender to passion than their relentlessly analytical 21st century counterparts (Gwyneth Paltrow and Aaron Eckhart). LaBute set out to prove that there is no reason on earth a costume movie has to be stiff, formalized, reverent to its own production values.

11) "Secretary" Steven Shainberg's candy-colored delight dares to reimagine Mary Gaitskill's dark short story as a romantic comedy. So what if the soul mates are a secretary (the peerlessly naughty and touching Maggie Gyllenhaal) who discovers she loves to be spanked and the boss (James Spader) who loves to dish out the punishment? Deliberately provocative while taking the predilections of its lovers beautifully in stride, the movie ends with a rapturous warm bath of romance that doesn't dissolve the erotic tingle it delivers elsewhere.

12) "About a Boy" In adapting Nick Hornby's novel, Paul and Chris Weitz have made a comedy that is a model of mainstream craft. As the self-involved hero, Hugh Grant (in a terrific performance) proves once again that he's never better than when he's playing a bit of a bastard. It's Grant's -- and the Weitzes -- neatest trick that he manages to let other people in his life without quite losing the wary cynicism that makes him so appealing in the first place.

13) "Punch-Drunk Love" Paul Thomas Anderson's irritating, strange and finally entrancing movie is a manic-depressive romantic comedy that aspires to the soul of a musical. It's a new-fashioned love song. Moving away from the sprawling Altmanesque scale of "Boogie Nights" and "Magnolia," Anderson finds something like the true spirit of romantic comedy, with his lovers, Adam Sandler and Emily Watson, perpetually teetering right on the edge of disaster. Sandler fans hated it, but mining beneath the rage of the gargantuan gnomes he has specialized in, Sandler manages to articulate the longing of a painfully inarticulate man.

14) "24-Hour Party People" From film to film, there's no predicting what Michael Winterbottom will do. This story of Manchester's Factory Records, which gave a home to bands like Joy Division, New Order and Happy Mondays, is alive with the playful invention and the joy of making movies, a what-the-hell spirit that is perfectly suited to the spirit of punk. As Tony Wilson, the impresario of Factory, Steve Coogan captures the slippery charm of a man who is equal parts smooth talker and true believer. And as Ian Curtis, the doomed lead singer of Joy Division, Sean Harris is terrifyingly believable in the manner of someone who sees no distinction between performance and life. "24-Hour Party People" is one of those rare movies that transports you to a specific place and time and allows you to feel the exhilaration and the gravity of people who, hearing a song, find their lives changed irrevocably.

15) "The Quiet American" The next time you hear someone blathering about what Harvey Weinstein and Miramax have done for independent movies, remember that Weinstein tried to shelve this superb adaptation of Graham Greene's novel about American duplicity in '50s Vietnam. A rapturous reception at the Toronto Film Festival saved it. Philip Noyce, shrugging off the big-budget anonymity of the films that have long marked his work, has made an intelligent, complex film of the Greene novel, exquisitely shot by the master cinematographer Christopher Doyle, with Brendan Fraser, the epitome of every Ivy League Kennedy era wonk who would lead us into Vietnam, doing his best work yet, and Michael Caine, peeling back layers of guilt, regret and emotional pain.

16) "Time Out" No movie this year got under my skin like Laurent Cantet's unnerving drama. The story follows a middle-class executive who has lost his job but, not telling his family, leaves his home every day pretending to still be working. You watch in dread as he drifts toward thievery and con games. And though the worst is averted, it doesn't dissipate the chill that hangs over this film: the question of how to hold onto our own identities in a society in which our only sense of self-worth is defined by our jobs.

Honorable Mentions: "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers," "Satin Rouge," "All or Nothing," "Enigma," "On Guard," "Me Without You," "Read My Lips," "Stuart Little 2," "Undercover Brother"

Pants-wetter of the year: "Austin Powers in Goldmember"

The Emperor's New Clothes Award: "Adaptation"

Worst Movie Ever Made: "Star Wars, Episode II: Attack of the Clones"

Shares