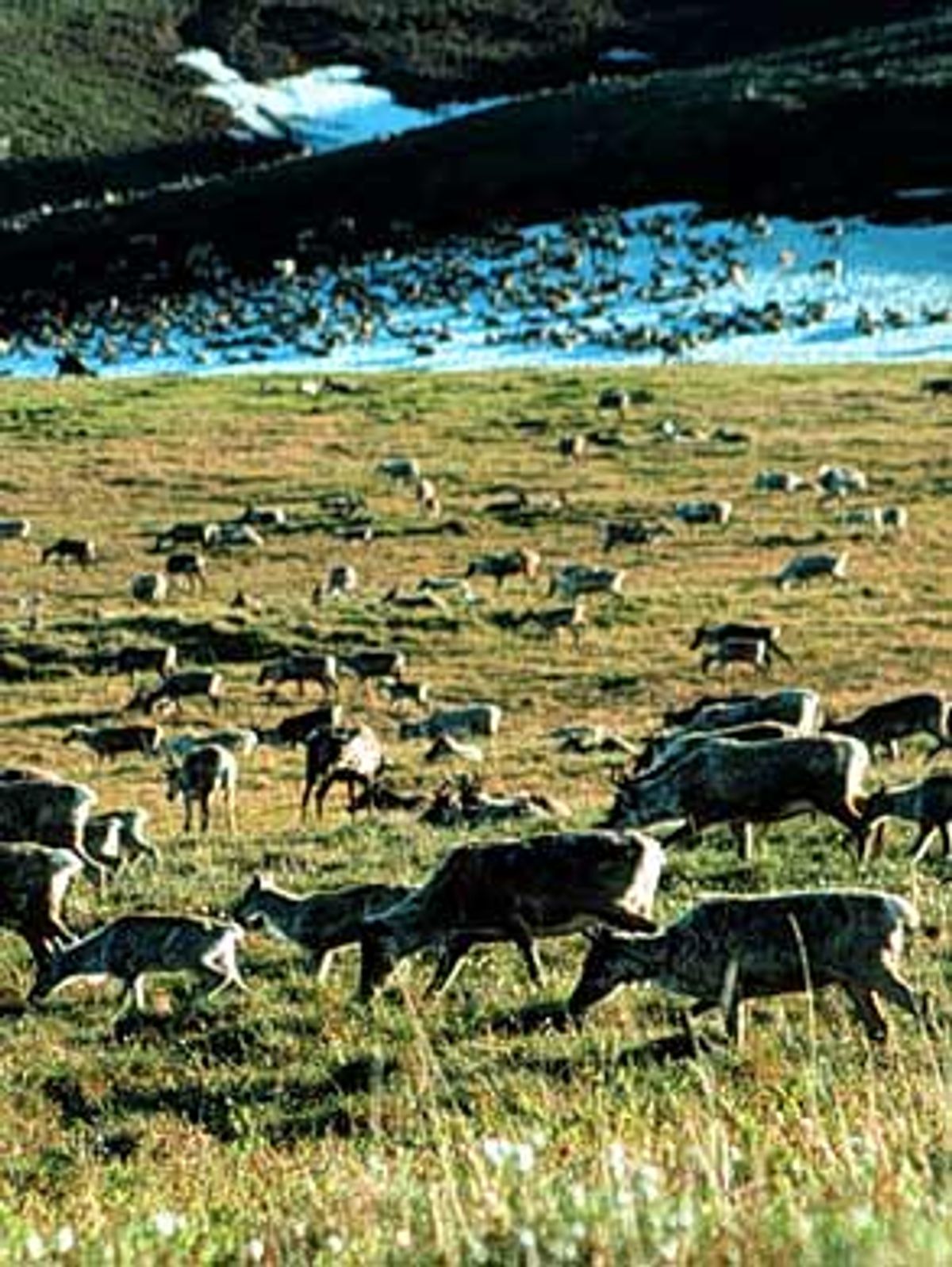

The tens of thousands of caribou meandering across the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge don't have any oil wells to dodge during their migration -- yet.

Last year, the federal energy bill that would have authorized drilling in the Alaska refuge died in the Senate. But in 2003, the oil industry's friends in Congress have pledged to reintroduce to the now Republican-controlled House and Senate plans to tap the refuge's fossil fuel reserves.

Just how much oil is actually at stake?

Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Environmental Protection Agency contend that the public is being misled by media coverage of the issue, which cites estimates anywhere between zero and 20 billion barrels of oil.

In a new study called "Sorry, Wrong Number: The Use and Misuse of Numerical Facts in Analysis and Media Reporting on Energy Issues," to be published in the "Annual Reviews of Energy and the Environment 2002," the scientists charge that everyone from Time, CBS News and the Financial Times to the Houston Chronicle have let advocacy, not science, drive the debate over drilling.

Jonathan Koomey, staff scientist and forecasting group leader at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and author of the book "Turning Numbers Into Knowledge," is one of the coauthors of the study. He has tirelessly debunked the coal industry's much-cited claims that the Internet is a major drain on electricity resources.

He told Salon why reporting about drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge often leaves readers believing that there's more oil there for the taking than there actually is.

Where do the estimates that reporters cite come from?

There is actually only one accepted source for the data on how much oil is available in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and that's the United States Geological Survey data.

What's interesting is that the media are quoting advocates on either side of the debate, who are taking numbers from that data that are convenient for their case.

Very, very rarely do the media folks go back to the USGS study or talk to someone at the USGS, even though all these numbers come originally from them.

How do so many different numbers come from the same data?

First, the USGS looks at the issue of how much oil is there, irrespective of whether you can recover it. They look at "oil in place." That's their starting point.

Then, independent of economics, there's technology that now exists that will allow us to recover some fraction of the oil in place. So, they make an assessment of the technically recoverable oil.

Then, they overlay the economics. If you compare the cost of the oil discovered in the 1002 area of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge [that part of the refuge in which drilling is being proposed] to the market price of oil, how much are you likely to find?

Then, beyond that, there are two rough categories of economically recoverable oil. There's what's called "conditional," and then there's "fully risked."

What's the difference?

The conditional analyses are generally used for areas like the continental United States, which are very, very thoroughly explored.

There's uncertainty about the amount of oil that you're going to find in the Arctic, because they haven't done the level of exploratory drilling there that they've done in other places where the conditional estimates are appropriate.

So, there's a lot of uncertainty about whether the oil is going to be extractable at the cost that we say. "Fully risked" deals with this issue by downgrading these conditional estimates to account for this additional risk.

So, what are the relevant figures to the debate about drilling in the refuge?

You're trying to figure out what could actually be extracted economically, given all the uncertainties. That's the number that people should be using.

Since 1986 or so the price of oil has pretty much ranged between $15 and $25 per barrel. That's in 1996 dollars, so these numbers would have to be inflated by 2 or 3 percent a year to compare them to the current price of oil.

At $15 per barrel in 1996 dollars, if you take the mean estimate, there's actually no economically recoverable oil there. If you look at the $20 per barrel case, it's 3.2 billion barrels. If you look at the $25 case, it's actually 5.6 billion barrels.

So, that's kind of the range that you would expect to see if the media was replicating the results of the USGS study.

What numbers are appearing instead?

Reporters are taking what the advocates say, and then they're reporting that range.

We plotted the ranges that appeared in something like 40 different articles. From these ranges that are quoted, the impression that you get is that it's between 8 and 15 billion barrels, and the range that I cited to you is between zero and 5.6 billion.

The impression that it creates is that somewhere around 10 billion is the real number, when the USGS number is zero to 5.6, and the middle range is 3.

Since the articles give such a wide range, everyone always just naturally goes to the middle, even if the reporters aren't going to the middle. The reporters may be accurately reporting what people are telling them, but in this case if they had gone back and checked the original source, they might present the information in a different way that would give readers a truer picture of what we know scientifically.

Why do you think that this data is getting presented this way?

I think what's happening is that the media is saying: There are two sides of this story, and we're going to give you both sides. The American Petroleum Institute says one thing, and the Natural Resources Defense Council says something else.

On the high end, these advocates say this, and on the low end, these other advocates say this. The problem is that if you look at these in the aggregate, the impression they give is that there are about 10 billion barrels of oil.

But if you just looked at the data and took a mid range, you'd come out at about 3 billion barrels.

Why is it coming out so high?

Some advocates are quoting numbers of barrels that are not even economically recoverable. In most cases, they're just oil in place, or they're technically recoverable oil.

The advocacy process, which is part and parcel to how information gets out into the world, is actually distorting the real numbers. This is a good test case because we know what the real numbers are -- they come from this one source. That's the beauty of this example.

Do you think that the advocates for drilling are purposefully misconstruing the information to help their cause?

I don't want to speculate about why they're doing it. All I know is that I can compare what the right numbers seem to be to how they're appearing in the media, and it looks like an overestimation. That's really the bottom line for this: An impression is being created that's at odds with the actual data.

Does either side in the debate dispute the veracity of the USGS data?

In this particular case, you don't have the advocates arguing that the USGS numbers are wrong. No one is really saying that.

But even though the accuracy of the original data is not in dispute, there's still distortion in how it reaches the public?

That's right. Then people start citing the numbers without giving the source, so it seems like it must be right. It's kind of common knowledge, conventional wisdom. And that's where you start getting into some really bad problems.

It's of concern because they're using these numbers in the debate over whether there should be drilling. This is an issue of public policy. The claim is that by drilling in the Arctic Refuge we will discover a certain amount of oil, and that then will achieve some sort of public goal.

Now, you could start asking other questions about that. OK, there's this public goal that you've defined, and this is one way to get there. One other option might be to improve the efficiency of the way that we use oil, and so how much does it cost to do that. How hard is it to do that? What are the barriers to doing it? Is it feasible? Is it something that costs more or less than the drilling?

But you can't even ask those questions if you're not looking at the right numbers. You can't make a real comparison.

If you're going to start looking into this public policy issue, you need to start by asking, What are the real numbers in terms of the cost of extracting the oil? That's why the economically recoverable number is so important. And then you ask what are the alternatives.

You could drill somewhere else. You could import oil from somewhere else. You could use oil more efficiently. In principle, you could make synthetic fuels, although that's probably too expensive, but there are some places that are doing that. You could substitute other kinds of fuel. You could have a hydrogen car.

So, there's all sorts of other options. And you could analyze these things if you were really concerned with the public policy debate. But first you've got to get the numbers right.

Shares