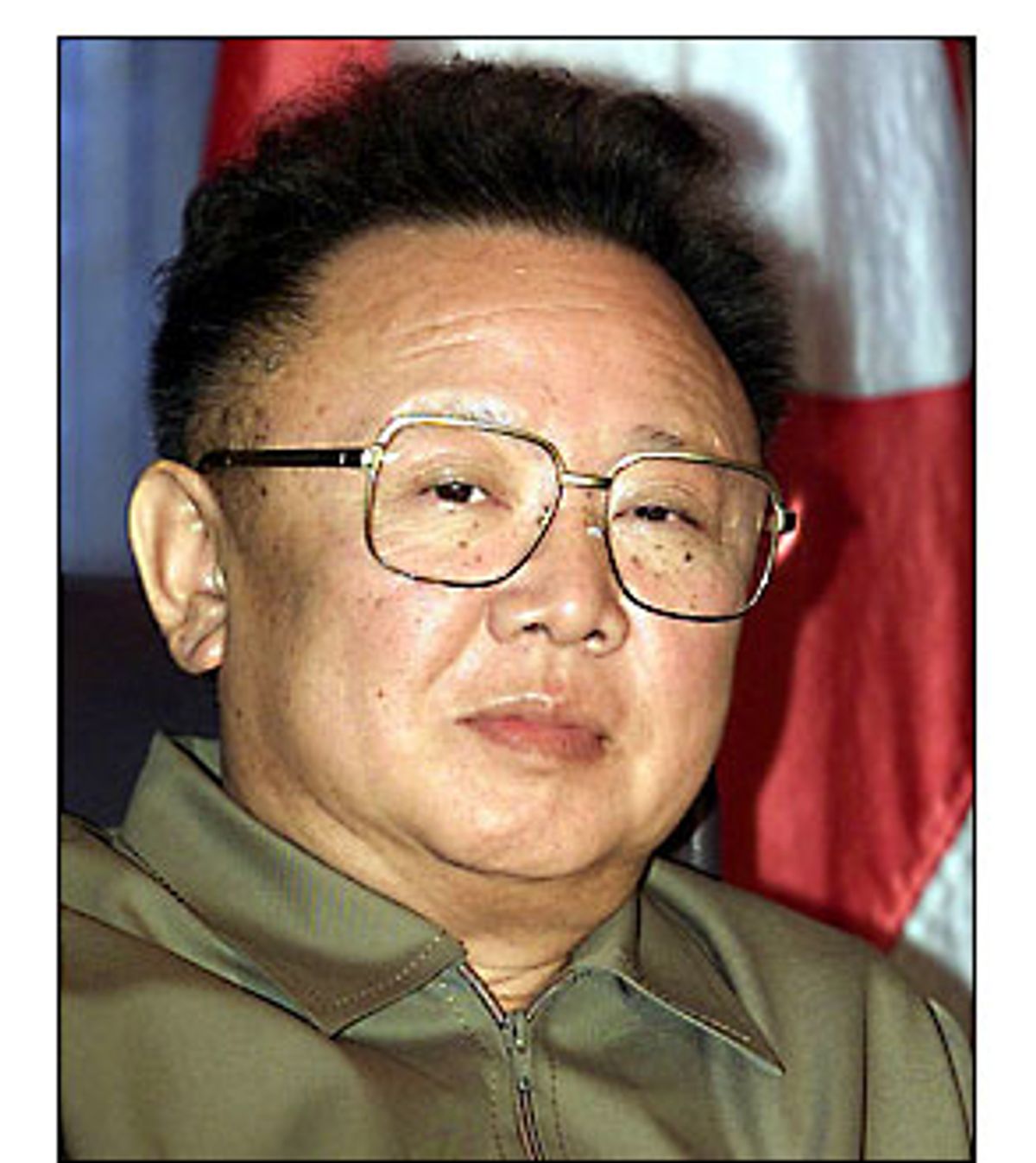

Kim Jong Il likes Daffy Duck and fast cars, and before he became North Korea's dictator he wanted to be a film producer. He was born on the peak of a sacred mountain, he says, and his birth was attended by thunder and lightning. In 1978 he had spies kidnap his favorite South Korean actress in order to improve North Korean cinema. His agents were implicated in the 1987 bombing of a Korean Air flight, killing 135 passengers, intended to scare away tourists from the 1988 Seoul Olympics. While his famine-starved people eat tree bark to ease their hunger, he dines on steak and cognac in the company of the "Pleasure Squad" -- a variety pack of imported blondes and Asian beauties.

He's also in charge of North Korea's nuclear missile program. And when his minions revealed the nation had restarted its nuclear weapons program late last year, and expelled arms inspectors, the unexpected provocation had U.S. diplomats asking a vexing question: How do you negotiate with a madman?

Dr. Kongdan Oh, coauthor of "North Korea Through the Looking Glass," insists the first step is to stop thinking of him as one. One of the West's foremost experts on Korean politics and culture, Oh gets impatient with the media's fixation on Kim Jong Il's cult of personality, and says the U.S. is focusing on all the wrong things during the current showdown. Kim is contemptible, maybe even evil, but he's not crazy, she says.

"He's a very bright, very daring, very bold dictator who knows how to control his society and act strategically to shock," she said in an interview with Salon. "In that sense he's no different from a person like Stalin or Saddam Hussein, and in many ways he's actually been more successful."

North Korea, which has the world's fourth largest army, has been dreaming of developing nuclear weapons since the 1950s, when Kim's father, the country's founder, Kim Il Sung, began trying to acquire the raw materials and know-how to develop an arsenal that might at least deter a U.S. first strike. Kim agreed to mothball the Yongbyon nuclear reactor as well as uranium enrichment facilities under the so-called Agreed Framework in 1994 negotiated by the Clinton administration. But he has signaled his intent to backtrack on the agreement at many points, and provoked the current impasse by restarting the Yongbyon reactor and working on uranium enrichment late last year.

On Thursday, the crisis U.S. officials won't call a crisis took two new twists. North Korea announced it would withdraw from the nuclear non-proliferation treat, according to the official North Korean news agency, KCNA. But earlier the same day, President Bush gave North Korea's United Nations envoy permission to meet with former U.N. Ambassador Bill Richardson, now governor of New Mexico, who had handled negotiations with Pyongang under President Clinton. Bush spokesman Ari Fleischer said the administration expected Richardson to hew to its official position "that we are ready to talk and that we will not negotiate."

But the administration's decision to let a former Clinton official play a role in the standoff was noteworthy, since Bush has frequently blamed his predecessor for appeasing North Korea. Upon taking office two years ago, Bush quickly reversed Clinton-era moves to normalize relations with North Korea, and last January he labeled the country part of an "axis of evil," along with Iraq and Iran. Now though, facing a showdown with Saddam Hussein, the administration has been anxious to ease the new tensions, and Richardson's involvement shows the length to which the White House may go in order to avoid a direct confrontation with Kim Jong Il.

But in the art of brinksmanship, the North Korean dictator is proving himself more talented than either Bush or Clinton, Oh says, although she credits Clinton with at least trying to engage with Kim and his oppressed, impoverished nation. As a policy analyst at the Rand Corp., Oh advised the Clinton administration before it signed the 1994 agreement, and she faults even the more engaged Clinton team for not fully understanding North Korean culture and society -- and not understanding Kim.

Behind the playboy fagade, she argues, lies a savvy manager and a nuanced mind. Kim's nuclear gambit may be designed to exact new economic aid from the West, or to get the Bush White House to return to the Clinton era path of normalizing relations. But according to Oh, until Americans understand his brand of North Korean realpolitik, Kim Jong Il has got the U.S. right where he wants it -- confused and unable to act.

Is Kim Jong Il a madman?

I could not use a word like madman. He is a very bright, very daring, very bold dictator who knows how to control his society and act strategically to shock his people and the globe. In that sense he's no different from a person like Stalin or Saddam Hussein, and in many ways he's actually been more successful.

But you're comparing him to dictators who have absolute control over their people.

Right. Dictators are brutal, power-hungry people with a control-freak mindset. Other than that, they are absolutely able managers of their own societies.

Is he a good manager?

If you don't call him a good manager, then what is he? The economy has been devastated since the early 1990s and yet the country is still standing together. Something is holding them together. He uses fear and punishment to control the population and potential opposition, and somehow he's preventing his population from standing against him. Definitely these are extraordinary skills and he's been very successful.

But then, North Korea itself is not a normal nation-state. They've never experienced a contemporary open society. Up until 1910, North Korea was part of the last dynasty of the Korean peninsula. After that Korea was colonized, so they moved from a despotic dynasty to very brutal colonialism, where the rulers were Japanese, and Koreans were treated as secondary citizens. And then after that it's communist rule. So if you look at the past century, North Koreans have never experienced a free society, so they have no comparison.

That's precisely why Kim Jong Il can do his job so well. He can combine an olden-days Confucian style mindset, where the ruler is always respected and regarded to be almost a different species, with the traditional Korean mindset, which is very much a father-worshipping, leader-worshipping culture, and he's manipulating that kind of mentality. Even in the worst economic situation he still has total control.

Do the North Korean people want Kim Jong Il as their leader?

That's a tough question. The core class, about 25 percent of the population, is trusted and treated royally by Kim Jong Il and his top cadre. Then there's the hostile class, also 25 percent, which is made up of potential opposition and people angry with the regime. In between them is a wavering class, 50 percent, and they can go either way.

There are people who say Kim is not that different from a cult leader. People will follow him no matter what.

He's not a cult leader, but he knows how to manipulate like a cult leader.

Well, are you letting him off the hook a little? As a Westerner, I look at his leadership and say, there are people starving in his country, and yet he's living it up, drinking cognac with his "pleasure squad" -- but there's no problem with this?

Yeah, but in the old days of the U.S. Congress, leaders were doing the same thing. They womanized and swindled too, so I don't think it's abnormal.

So you're saying it's not that different?

I don't think so. European history creates a lot of madmen, but somehow because he's supposedly a subdued, quiet Asian guy there's a lot of attention focused on his personality and his style of leadership.

So it's a question of Western perspective ...

Yeah, Asians look exotic. And Kim Jong Il loves fast cars and high fashion, all these things, so I think the media hypes the image of him as a scandalous leader. By painting him that way, by making him look like just a crazy, irrational leader, the media creates even more misunderstanding among the American population. If you look at the U.K. royal family, they're even more bizarre than Kim Jong Il. Journalists need to ask more serious questions, rather than focus on his personality and inclinations. The only [crazy] thing that he did was his state-sponsored terrorism -- sending out agents [with] bombs so that the world would not show up for the South Korea Summer Olympics. That's a little crazy.

But why would a poor country spend so much money on missiles?

North Korean missile development is not about blasting the world, but about military deterrence, because it's a very weak, isolated, lonely country that nobody likes. And nuclear weapons are the poor man's bomb. Conventional weapon development costs a lot of money, but if you're a nuclear power you're suddenly special, and your image is one of a mighty power that nobody would like to touch. In a sense you can be a very safe porcupine, without worrying about being attacked. North Koreans think this is a nice way of protecting their regime, although Americans don't translate it that way. I don't think that anyone's interested in North Korea's longevity, because it's a bad country with a bad dictator. But if the leadership and the nation have this kind of power, then the whole game of strategy is different. In that sense the North Korean nuclear issue is not just a bluff or a bargaining tool.

Does our current foreign policy reflect an understanding of all of that?

U.S. foreign policy in Asia has always been written by events, by crisis. There's never been a long-term strategy for truly understanding the culture and history of individual countries. We do well with China and Japan, because they're such major countries, but we tend to leapfrog the Korean peninsula and you can imagine our contentious attitude toward understanding the North Koreans. Until my book came out, no one had written a comprehensive history of North Korea.

U.S. policy makers usually don't give a damn about understanding North Korea. The best example is in 1994, when I was working for the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, and I was involved in the policy process. I was telling the government elite that you've got to understand the mindset and cultural background of North Korea. Only then will you know how to negotiate and understand what kind of framework you're signing for. But they completely ignored that kind of advice, and now we see a repetition of the same crisis. As long as we keep that kind of attitude, there will be numerous other crises waiting for us. Believe me.

What's the minimum Americans need to know about North Korean culture and history to understand this crisis?

Well, I think that the average American in Kansas may not even distinguish that there are two Koreas. The amazing thing is that when the South Korean delegation, our allies, arrived in D.C., some of the government security people who weren't very well-educated asked, "What Korea are you from?" That's the level of overall awareness of the global situation.

It's common sense that before we try to engage North Korea on missile issues, we need to have a bare minimum understanding of their society and culture. Secondly, we have to listen to regional policy makers -- what South Korea is saying, what Japan is saying -- and engage in some kind of consensus building through serious consultation, rather than assume we are the one who dictates the course of the action.

Can you compare the way the Clinton and Bush administrations have handled North Korea?

There is a huge difference. The Clinton administration used the word "engagement" -- engagement and dialogue were the basic model. Bush [has emphasized] containment, deterrence, and vigilant observation of what North Korea is doing.

I was involved during the Clinton era. I think they were a little too relaxed after 1994, a little too sure that things were under control. There were criticisms in 1998, a feeling that we have to have IAEA [the International Atomic Energy Agency] push inspections to find out what's going on in North Korea. In that sense I think the Clinton administration's rather romantic treatment of North Korea's weapons of mass destruction is the predecessor of today's problem.

But President Bush's rhetoric is sometimes too simply stated and too harsh.

In what way?

His moralistic judgments, "axis of evil," us vs. them, are very black and white. Those kinds of descriptions are not creating any positive response from the region, even from European Union members, in dealing with the crisis. In that sense I think glib-tongued President Clinton managed to talk about North Korea more smoothly. President Bush is creating more problems, more conflict, potential friction even with his allies.

What should President Bush do?

Today? Well, he's not making a lot of statements other than we won't attack North Korea, don't worry about it. But water was already spilled, in a sense. I think his "axis of evil" speech is the permanent image people have of him, as a morally righteous president demanding the world to be either with us or against us. That sentiment is widely shared, but the biblical terminology of "you are evil, so by implication we are not" is not conducive to building consensus in Asia on policy issues, particularly in the post 9/11 era.

What do South Koreans want?

South Korea has a deep dilemma. It's unlike the Cold War days. During the Cold War, South Korea felt North Korea posed a great threat, but gradually South Korea became an economic power and they saw North Koreans who were hungry, constantly begging for international food aid. The threat perception is changing very rapidly. They saw North Koreans as hungry brothers and sisters suffering under the dictatorship. The dictatorship is hated, but nonetheless its people are victims of the system. Many younger-generation South Koreans who grew up in the post-Korean War or post-Cold War era treat North Koreans as starving family members rather than a threat. They don't think nuclear missiles will be exploding the next day. Many of them think that the development of nuclear missiles is kind of like a survival tool, for military deterrence, to bargain for export items. So as a stalwart ally of the U.S., South Korea is between a rock and a hard place.

Is there an immediate military risk?

I don't think North Korean leaders are stupid enough to bring the nuclear threat on themselves, unless they felt they were pushed into a corner.

Other than not pushing North Korea into a corner, what should the U.S. do?

Let the world be a part of the decision-making process. It's already been brought to the U.N., and we need to work in concert with them and the regional powers.

Shares