When I sent my 17-year-old daughter off to college a little over a year ago, what I saw was a confident, smart teenager excited about the future and eager to get off on her own. She was a dead shot from the foul line in basketball and a whiz at math and physics, she looked gorgeous, and she could write circles around her dad. I remember thinking, with a mixture of pride and regret, as she headed skyward, "Well, that's one child all grown up and off on her own. One more to go."

That December, at the end of the first semester, my wife and I waited excitedly at the airport for our daughter to come home for the holidays. All that term, she'd been sending home regular e-mails that talked of funny adventures, good times with zany friends, the occasional problems with courses or boys -- in short, a typical first semester away at school.

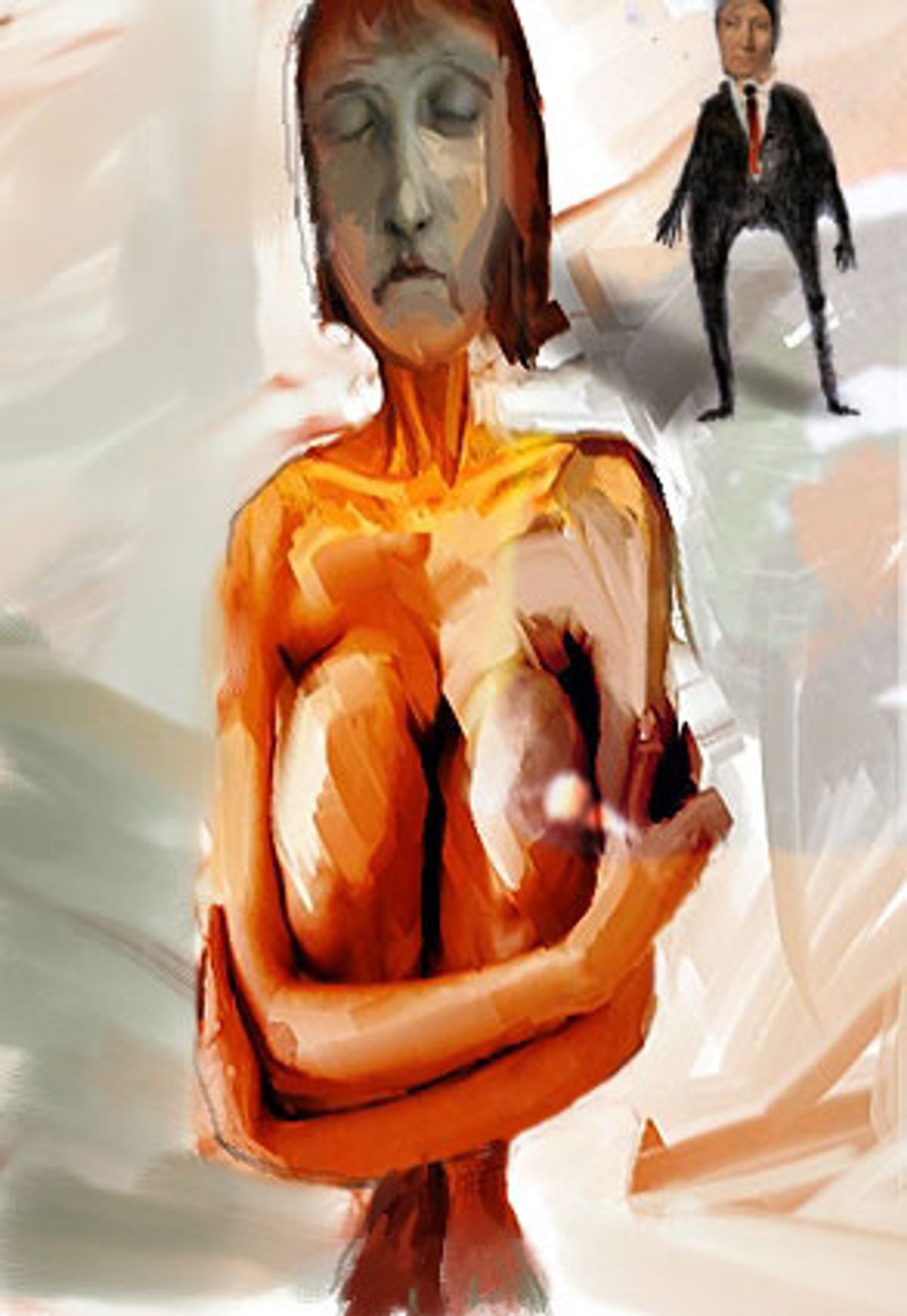

We expected an exhilarated student; instead we were confronted with an apparition: A 5'6" scarecrow pushing 100 pounds, about 35 pounds less than when she'd headed off to school, who looked so frail and terrified that I wasn't sure it was my child I was staring at.

We were shocked into silence. We didn't know what to say or how to bring it up. On the ride home, we talked about school and the plane flight, and the whole time I had this lump in my throat -- a scream that wanted to come out, a panicked plea to know what the hell had happened. Finally, after almost 15 minutes or more of this uncomfortable avoidance, in a voice that was more of a whimper, she asked, "Aren't you going to ask what happened to me?"

We did, and we are still asking what happened. There are, we've gradually learned, no easy answers. As it turns out, we are hardly alone. Colleges -- especially top colleges and universities -- are reporting that stressed-out and exhausted students are turning to dangerous and self-destructive behaviors with alarming frequency. Whether that is the result of over-the-top parental pressures to succeed, a byproduct of society's hyper-focus on getting ahead and securing a good job, a response to the spiritual vacuity of our modern consumer culture, or all of the above, it's clear that young people are crashing and burning in college at an alarming rate. And eating disorders are one of the more dangerous ways they're doing this. The National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders estimates that 7 million girls and women, and 1 million men and boys, suffer from anorexia.

Up to that moment at the airport, anorexia was not a disease I had given much thought to. From that awful day, it became my life. It became my wife's life. We read about it. We worried about whether it would kill our daughter. We struggled with its pernicious effects on our own lives. We tortured ourselves over what role we might have played in driving our daughter to it. We wondered if it would ever go away.

The first thing we did upon discovering that our daughter was facing a life-threatening health crisis was to call around frantically to find treatment options. Fortunately, our insurance plan covered anorexia treatment and psychological therapy. We located a nationally known program in the area that had both an in-hospital program and a day program, and after consulting with the head of the program, a well-respected psychiatrist specializing in eating disorders, we opted for the day program.

Those first few weeks were a nightmare. I would find myself crying inconsolably in the middle of the night, convinced that I was going to lose my daughter (anorexics can simply die in their sleep, victims of chemical imbalances in their blood that lead to heart failure, or they can die slowly as their starvation leads to the wasting away of heart muscle). In those dark moments alone, I was certain I was to blame for something I'd done or said sometime in her young life; or maybe I simply failed to see, early on, that something had gone terribly wrong.

We'd always been a close family, open about discussing things, not judgmental, not punitive. I couldn't imagine what my failings had been, but I was certain they were there. My wife and I were both consumed with feelings of guilt, panic and helplessness.

My daughter assured us that it wasn't our fault. Maybe she believed that. We weren't so sure. We had, after all, dragged her around through several difficult moves when she was younger, including moving to a new town just as she was entering high school -- a particularly difficult time for teenagers. We had been slow to respond to vicious teasing she had suffered at one point in elementary school. And while we had never pressured her to get into a particular college, we certainly, as two intellectuals ourselves, had always cheered and encouraged her academic success, which might have led to her feeling pressure to excel.

Her own explanation for her anorexia was "stress." She could never really define what the stress was, but clearly going away to college triggered something in her that made her turn to starvation as a response.

It was bizarre to watch someone, who only months earlier had regularly sat at the table eating normally, enjoying conversation, suddenly slip away to her room whenever there was a family meal on the table, taking her own tiny portions of a very small list of acceptable (non-caloric) foods to her room.

The closest thing I can compare it to is a drug or drinking habit. We saw the paraphernalia of self-abuse -- the little plates, the empty bags of frozen corn, the wrapper for a bunch of celery, the empty can of fat-free tomato sauce. What we didn't see was anything substantial being consumed.

But with treatment, my daughter was back to a marginally healthy 120 pounds six weeks after she walked off that plane. She got a part-time job and began taking a couple of college courses as a general studies student. She was in therapy, seeing a psychologist who specialized in anorexia and bulimia. Things seemed to be improving. She even made arrangements to transfer to another college closer to home for the fall term. As my daughter approached a healthier weight, I started being able to sleep again and to be able to concentrate on my work.

But over the summer we could see that things were not resolved. Our daughter was still eating like a dieter, though she was managing, with careful monitoring, to maintain her weight at between 120 and 125 pounds. But she was morose much of the time, rarely seemed enthusiastic about anything, and kept talking about being nervous about things she had never before worried about, like how she'd do in her courses in the fall. Any comment from us about her eating habits would lead to accusations that we didn't trust her, or complaints that we were making her feel that she was a "disease," not a person.

Still, if she hadn't yet reached an understanding as to why she had fallen into this problem, we felt confident that she at least had a grip on her disorder, that she knew how to control her impulse to starve herself.

We were cautiously optimistic when we sent her off to school again this past fall. Her therapist agreed that she was much improved. He felt she needed to get off on her own again so that she could gain the sense of being an adult, in charge of her own life.

This time, however, we vowed to stay in close touch with her. She was only a few hours' drive away, and we decided we'd make frequent visits -- at least once a month.

She promised to make regular use of the school's health services, which we'd been assured included a resident psychiatrist, several staff psychologists, and a nutritionist, all of whom specialized in eating disorders (an epidemic at American colleges, we were told by school officials). In addition, she agreed to get weighed weekly at the heath services office.

After a few weeks, reports from our daughter were basically good, but she said she was "having trouble" getting an appointment with the psychologist. All the available hours, it seemed, conflicted with her course schedule. She was eating, she assured us, but she didn't tell us her weight. I see now that we should have known better at that point than to trust her to take care of herself. (As we have subsequently learned, anorexia, like drug addiction, involves a good deal of deception.)

Four weeks into the semester, she called one evening. Her boyfriend had insisted that she tell us to come get her immediately. When I leapt into the car the next morning, I didn't know quite what to expect. What I found was worse than I could have imagined: a skeletal girl of just 90 pounds who could barely lift anything to help me move her out of her dorm room.

"How could you have done this to yourself?" I asked on the ride home. "Why didn't you go to the health service for help?" Obviously frightened at what had happened to her, she said, "I kept thinking I could fix it before going to see them. I was afraid that they'd send me home if they saw how much weight I'd lost. I was afraid you'd be angry at me."

Why hadn't she eaten for the five weeks she had been away? "Everything was just so stressful," she answered vaguely. She had been doing well in her classes and liked her work-study job. I did notice, however, that she didn't seem to have any friends she needed to say goodbye to as she moved out.

We've learned over this terrible year what many others who have endured this hell learned before us: That anorexia is not usually about being thin; it's about control. Contrary to a commonly held belief among the dwindling number of Americans who have not been touched by the disease, young people who fall into the grip of anorexia (15 percent of anorexics die of the ailment) are not, for the most part, trying to look like some magazine icon; they're trying to assert some control over a life that they feel is not really theirs. In our daughter's case, it seems she was reacting to a situation of being in a society -- school -- not of her own choosing. At least part of her not eating may simply have been a way of avoiding having to be in a social situation -- a student cafeteria -- that she found uncomfortable.

There is often an element of depression in anorexia, and also, as in our daughter's case, of obsessive-compulsive behavior. There was the apparent inability to get enthusiastic about anything. And there were the lists she made. She would plan every detail of her day on paper.

It was back to the hospital for my daughter, this time as an in-patient. She was clearly suffering from bone loss and, worse, was putting her heart and other vital organs at risk. It was urgent that she gain back some weight, and quickly.

She hated the idea of entering the hospital, and at 18, she could have refused, forcing us to commit her against her will. Fortunately, she agreed to submit to the program voluntarily. But she became more withdrawn than ever, curling up into a chair during family therapy sessions until she looked like a small child, and shaking one leg spasmodically in a severe kind of nervous tic, especially whenever she was spoken to or when she was talking herself. In those sessions, we learned that our daughter suffered from intense anxiety -- about school, about friendships, etc. -- and that she had a difficult time handling any kind of conflict.

It also became apparent to us that our daughter was and had been deeply depressed -- not just since the onset of her anorexia, but during high school as well. And though we suggested repeatedly to her therapists over the course of almost nine months that maybe she should be prescribed antidepressants, until last autumn they were unanimous in saying that they didn't think she needed them.

A primary reason for their reluctance to medicate our daughter was the same one that, up to a point, prevented us and, for a very long time, prevented her doctors from realizing that she was depressed. Anorexics, we have learned, are wonderful actresses, and our daughter seemed particularly adept. She might act depressed in our presence, but rarely did she do so in the presence of medical professionals, who for months misdiagnosed her as having a relatively minor, and recent, case of anorexia. Finally, once she was in the hospital, that diagnosis changed. After a few weeks of observing her round the clock, they realized hers was a severe case and that she was a prime candidate for the drug Zoloft.

After the Zoloft took effect, we began to notice dramatic improvements. Our daughter began eating more easily. She regained 25 pounds. She began to be able to eat socially and to talk about her eating habits. Best of all, for the first time in more than a year, she began to laugh and joke like her old self.

My wife and I are starting to laugh and joke, too -- and to think clearly for the first time in a year about things other than our daughter's health. We're not sure where all this will end. We're still a little skittish about feeling too confident. It's clear that anorexia is not something that simply goes away, like a case of the flu. It's something that, barring a miracle, will be with our daughter for years -- perhaps for her whole life.

These days, my daughter still finds it hard to eat socially, preferring to eat by herself, and as her weight has approached a normal range, she seems increasingly careful about what and how much she consumes. But I no longer believe, as I once did not too long ago, that this disease is something that will ultimately destroy her. Anorexia is something she can beat, something she can learn to master.

Looking back on this year, I am angry about a lot of things and grateful for others. I'm grateful for the treatment my daughter received from the eating disorders program, but angry that her therapists took almost a year to figure out that she could benefit from medication. I'm angry at myself for not recognizing the signs of trouble earlier, when my daughter was in high school. The clues were certainly there -- the days she'd stay holed up in her room, her complete lack of interest in after-school activities, her avoidance of social gatherings -- but we just assumed we were dealing with typical teenage alienation.

My daughter was a girl who earned straight A's all through school, who scored 1560 on the SAT , and who got into every top school she applied to. This was a girl who didn't do drugs or drink, and who didn't engage in casual sex or get into unhealthy relationships. During her adolescence, I would think back to my own teenage years, which included weekend binge drinking, drugs and all sorts of tortured relationships with girls, as well as a lack of communication with my parents. I figured, erroneously, that if she didn't have the kinds of problems I'd had, her problems could not have been serious.

Finally, I'm angry that school and public health authorities are so clueless about what constitutes a major health crisis. Our school district, like many others across the country, holds regular health sessions to counsel kids about anorexia and bulimia. They train kids to be "peer counselors" (our daughter was one), to help out other kids who exhibit such problems. But these programs are as ineffective as the "Just Say No" anti-drug and anti-sex campaigns. They appear to be fatally flawed in two ways: First, they focus on eating, and the need to be healthy, as though kids are falling into anorectic or bulimic behavior out of nutritional ignorance or because they're afraid of getting fat; and second, they assume that by warning kids about the disease, they will help them avoid it.

At this point, it seems clear to me that if a kid is going to become anorexic, no amount of cautionary warnings will prevent that from happening. The only thing that really offers the hope of prevention, most experts agree, is early intervention with therapy, to attack the underlying problems that push a child toward anorexia. It's parents and teachers, not the children themselves, who need to be alert to the problem and who need to intervene when the signs start to appear. Schools need to start offering preventive programs aimed not at kids, but at parents and teachers.

No teacher at my daughter's high school ever asked why she never ate lunch. Even as she wasted away at two different colleges, no professor, advisor or residence advisor took her aside to ask what was happening, no friend or roommate alerted an advisor, and no one called her parents to say something was wrong. My guess is they simply didn't know what to look for.

Our lives have changed dramatically since last year's airport shock. I used to talk with my daughter about what she wanted to do after college. Now I no longer think or care much about her career plans. I just worry about her current happiness (and of course her weight, which we require her to have monitored weekly as part of her deal to go back to college). I encourage her to enjoy college for itself, not as a step toward something else.

All this seems to come as a relief to her. She never brings up career plans anymore and instead talks about her courses and her current life, which I take as a good sign. If anorexia is about wanting to feel in control, it makes sense to live more in the present. No one can control the future, but we do have much more ability to control our present -- to choose that which makes us happy and reject that which makes us unhappy or uncomfortable.

As for my younger daughter, who's still in grade school, I focus on her being happy about herself and her school.

This isn't a bad way to be -- living in the moment and making the most of it -- and it reminds me of my own life in college. While getting a great education, I spent four years without giving any thought to a career.

Meanwhile, I have learned over this past year what I now consider to be the biggest lesson of parenting: It's a job that never ends.

Shares