Remember how smoothly Bush’s tax cuts sailed through Congress in 2001? As Washington consumes itself with debate over the administration’s new plan for expanded cuts, one thing appears clear: It won’t be as easy this time. Democrats are promising a fiercer fight, and even Republicans are wondering whether the proposal is too costly or will do anything to “stimulate” the economy.

They’re right to worry. The economy still teeters on the edge of recession, and tension is mounting over whether the Bush administration is pursuing the right strategy to fix what’s broken. There’s little evidence that policies so far championed by the White House — such as the $1.35 trillion tax cut passed in 2001 — have done (or will do) the vast majority of Americans much good. Whatever small comfort you might have taken from your share of that last tax cut — the $300 tax rebate check you received in the mail — is due to Senate Democrats. Meanwhile, with unemployment at 6 percent, and 100,000 jobs lost in December alone, the president and congressional Republicans allowed jobless benefits to expire for 800,000 people before they took any action to extend the money.

But let’s assume, for the moment, that against all logic and reason the new Bush tax cut passes as is. What’s the worst that could happen?

The first thing to look at is what economists call the “short run,” the two or three hardscrabble years directly ahead. One problem with the Bush plan is that nothing good will immediately come of it. With the various Democratic plans currently being discussed, you might get another rebate check or some relief from the payroll tax. You could go out and buy an iPod or a couple months’ groceries. But don’t expect a meal ticket from the president’s proposal. The $100 billion the Bush plan will put into the economy during the first year and a half after its passage is tilted toward the wealthy — people who, many argue, won’t spend it — and therefore won’t help the economy all that much. The Bush plan would also do nothing to help fiscally burdened state governments; and if those states must resort to tax increases to balance their books, the whole tax cut idea ends up a wash.

But that’s not the worst thing about the Bush economic record. The president and congressional Republicans plan to make the cuts permanent, an idea that would lead to deficits that George von Furstenberg, an economist at Indiana University, worries are “too high for comfort.”

“After giving away trillions in ten years in the first round and an other $674 billion in the second round, and even counting some supply-side effects from that, we are looking at a structural situation,” von Furstenberg says, referring to deficits above 3 percent of the GDP. While he speculates that the economy will recover by about 2006 or so, with full employment returning then, he says that if you count the cost of the tax cuts, domestic spending items like the healthcare proposals currently on the table, and the cost of a possible war in Iraq, expenditures by that time will be enormous. “And so we’ll see that this will not be a sound and balanced recovery, and that we are in fact bleeding from too many deficits,” he says. The recovery will slip, he says, and we’ll soon be back in another recession.

All this wouldn’t be so dire if the nation could fully comprehend the calamities now and — in the 2004 presidential election — vote in a new economic team. But while “I think we are making for a rather unstable future with the kind of policies that are being hatched,” von Furstenberg says, “that may not become apparent immediately. You won’t see it until the truth can no longer be concealed, which will be after 2004. You’ll see it when you look at the budget that will come out in 2005 — and the hope [for the Bush administration] is that for two years more we won’t have to face the full budgetary implications of all this.”

In a speech to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on Jan. 15, Mitch Daniels, the White House budget director, said that he expects a $200 billion deficit this fiscal year — which ends in September — and a $300 billion deficit in 2004. The numbers did not include the cost of a war in Iraq, which the administration has said would be at least $50 billion. But Daniels shrugged off the rising deficit numbers, telling reporters that “we ought not to hyperventilate about this,” because “by any historical measure, these are manageable deficits.”

Sheldon Pollack, a professor of business law at the University of Delaware and the author of “Refinancing America: The Republican Antitax Agenda,” agrees that running a small deficit during bad times isn’t a bad thing. But he worries, also, that spending — especially on defense — could spiral higher.

Von Furstenberg warns of the same thing. “What you’ll have is a loosening of the federal purse strings enormously. Because in this self-indulgent climate, when you have an optional war, a war you choose to have, you really can’t get people to think about austerity for any amount of time. In a sense you have to grease the pinwheels for increased military expenditure by giving in on domestic spending.”

What’s so bad about deficits? Liberal economists say that deficits drag down economic activity, but conservatives increasingly reject that idea and advocate the fanciful notion that deficits will actually help to shrink the size of government.

Do Americans want a smaller government? Some might say they do. But if you’d like the federal government to spend more on healthcare, or to protect Social Security, you’re not asking for a smaller government. If you want to keep up an eternally overwhelming defense apparatus, you’re not asking for a smaller government, either.

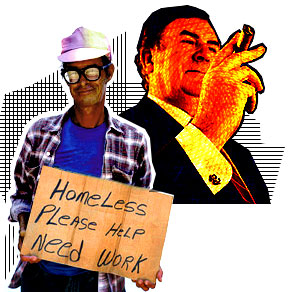

And that suggests the final impact of Bush’s voodoo plans: a wealthy superclass, earning millions on their dividends, paying nothing on their estates, and the rest of us, stuck in an unstable economy, and the Treasury too drained to help. What’s the worst that could happen? An economic disaster.