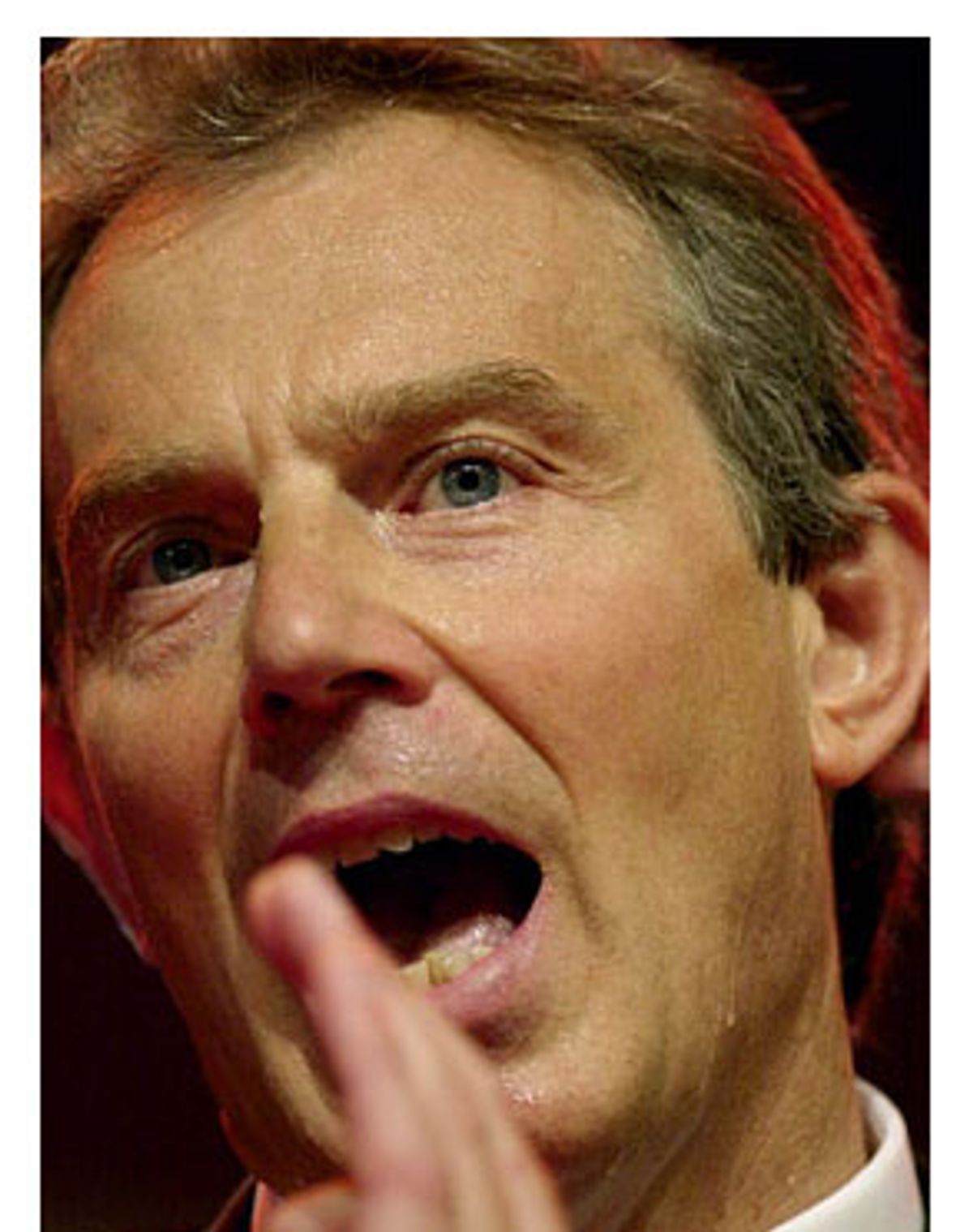

Fielding questions at his monthly, American-style press conference last week, Britain's Prime Minister Tony Blair spent an hour defending his firm alliance with President Bush on the possible need to wage a preemptive war on Iraq. Blair's controversial stance, along with his commitment to sending 40,000 troops, has dominated the public debate in Britain in recent weeks, with increasing signs that his staunchly pro-American position is exacting a political price at home.

Speaking from the podium, Blair tried to say all the right things, soothing British anxiety about the war by stressing it was not inevitable -- "of course, no one wants conflict" -- yet at the same time holding firm on the goals. "Disarmament," he said, "is inevitable."

Blair talked and talked and talked, responding thoughtfully to 26 war-related questions. Yet despite all the talk, and especially for someone who sees himself as a master communicator, Blair is not scoring many debating points. He still faces a jittery British public, most of whom, according to a recent survey, think the real motivation for war is to seize control of Iraq's oil. Longtime allies France and Germany have just abandoned him by coming out strongly against the war if weapons inspectors cannot uncover obvious proof of Saddam Hussein's misdeeds. And worse for Blair, there's a rebellion brewing within his own Labour Party, including some of his own cabinet members who fear that British involvement in Iraq would prove catastrophic for the party, not to mention the country.

"This war may be a bigger test for Tony Blair than it is for George Bush," says Simon Henderson, a London-based adjunct scholar of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

For now, Blair is hoping that arms inspectors will be able to deliver clear proof of material breach and prompt the U.N. Security Council to pass a second resolution authorizing war against Iraq, and that a sizable international coalition will then sign off on the military efforts.

"If that's the case, the war opposition at home will sit on its hands," says Martin Kettle, columnist for the Guardian, a liberal London newspaper. British polls, like those in the United States, show a vast majority want clear U.N. support for war before the country agrees to fight -- especially since Blair has committed most of Britain's army to the war effort.

The worst-case scenario for Blair, though, features the U.S. opting to go it alone against Iraq without the U.N.'s blessing, thereby forcing Blair to make perhaps the most difficult decision of his political career. "He'd be a fool to go along," says Kettle. But if he did, "I think it'd be the beginning of the end for him."

That grim possibility grew much more vivid this week when France and Germany announced they were united against the war and might block any attempt by the White House to win an authorizing resolution at the U.N. By using their power on the Security Council to block U.N. approval, both countries could put Blair in a terrible bind and create real havoc for the White House.

Blair represents the linchpin for the United States' hopes of building an international coalition for war. Even with Blair onboard, the U.S. so far has not mustered much of a coalition. The Security Council -- including permanent members Russia and China -- appears overwhelmingly opposed to military action at this time, based on the current evidence against Saddam. Turkey, usually a reliable U.S. ally, is balking, and most governments in the Arab world have warned that hasty action could have dire repercussions. If Britain bails, the White House cannot even pretend to have the backing of an international alliance.

That's why if there's anyone outside Bush's inner circle who might actually have veto power over the war today, it's Blair. Polls show that a strong majority of Americans badly want allies to support a U.S. strike on Iraq. If in the coming weeks Blair, feeling immense political pressure at home, were to emerge from 10 Downing Street and announce he could not support a war with Iraq or, specifically, the timetable the U.S. was using, the decision could have historic repercussions.

"If Blair pulled out of military action, the U.S. would find it very hard to go to war," says Nile Gardiner, a former foreign policy aide to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. "America would have to go to war without any allies, and I don't think Washington has public support for that. In a way, Blair holds the key to the war."

Given Blair's stated determination to maintain Britain's "special relations" with America, longtime Blair-watchers doubt the prime minister would back out on Bush now. But for those anxious about an invasion who are trying to piece together a scenario where war could be averted, Blair's role holds some tantalizing possibilities.

Even though he's a philosophical soul mate of Bill Clinton who also moved his left-leaning party to the middle, Blair's staunch loyalty toward America's conservative Republican president on Iraq has caught some by surprise -- including a large chunk of his own party.

But listen to Blair long enough and it's obvious that, like Bush, he's convinced that if Saddam is not disarmed, the Persian Gulf dictator will pose a grave threat to the West for years to come. And Blair, a man of strong Christian beliefs, also seems determined to help liberate the Iraqi people from Saddam's tyrannical grip.

But politics are clearly at play as well. The reality for British prime ministers today is they don't have much choice but to follow U.S. foreign policy, particularly on monumental issues like war and peace.

"Tony Blair knows that unless Britain does become involved and supports the U.S. on Iraq, Britain loses its position at the top table of world diplomacy," says Henderson. "We're only there as allies to the United States. Otherwise, apart from a permanent Security Council seat, we're [lumped together] along with Germany and France and other people who dither."

Diplomatically, nothing would upset Blair more than seeing Britain confined to the international sidelines, or himself being labeled a pro-European dove. "Blair's alliance with Bush is not based on an instinctive, pro-American gut feeling," notes Gardiner. "Blair's a very clever politician and understands maintaining strong ties with the United States is crucial in terms of Britain's power and prestige. If Britain didn't fight alongside the U.S. and it went into Iraq, it would be catastrophic for the 'special relations,' and Blair understands that."

"Special relations" is a phrase coined after World War II to describe the importance of the U.S.-Britain alliance, and it highlights how Britain, often alone among the European powers, routinely sides with the United States. That's why, on paper, France and Germany's refusal to back a preemptive war is not surprising. But their move takes on added importance with regard to a possible second U.N. resolution that so many American and British citizens want as a precursor for war.

There was a feeling early on in the discussion of war that because the U.S. seemed so committed to attacking Iraq regardless of international opinion, the smart move for Blair was to embrace Bush and in that way increase Britain's leverage in the end.

Blair supporters insist the strategy has worked, noting that only after Blair prodded him did Bush agree to take his case against Saddam to the U.N. and urge the return of weapons inspectors to Iraq. Blair defenders also highlight the upcoming summit scheduled for the end of the month at the Camp David presidential retreat, where Bush and Blair will meet one-on-one to discuss Iraq.

"The United States sees Blair as such an important player, they need to consult him, to give him a military say, whereas no other leader has a say," says Gardiner, currently a visiting fellow of Anglo-American foreign policy at the conservative Heritage Foundation in Washington.

It all proves that Britain can still "punch above its weight," as the local saying goes, meaning the country's influence on the world stage far surpasses its military strength. And for a nation whose empire once stretched across the entire globe, that notion of still being in the mix has deep appeal.

Blair's arguments for war would sound familiar to American ears, since they so closely mirror the White House talking points: By maintaining weapons of mass destruction, Saddam has been in violation of U.N. disarmament resolutions for years; he poses an immediate threat to the West; the U.N.'s authority is being tested; rogue states should no longer be allowed to nurture terrorism.

But domestic critics, some of whom dismiss Blair as Bush's "lap poodle," argue that Washington has simply been paying lip service to London, and that Blair's contributions have had little or no impact on the actual war plans. They doubt that Blair's third-way approach will be taken seriously at the Pentagon when it comes time to decide whether to invade.

But that may underestimate the subtle, and crucial, nature of Blair's role. The White House has continued its troop deployments to the region and escalated its rhetoric, warning of "time running out on Saddam Hussein"; France and Germany have expressed adamant opposition to war. Blair, meanwhile, has seemed to act sometimes as a buffer, other times as a bridge, in Euro-U.S. relations.

In recent weeks the prime minister has been trying to soothe British fears. His foreign secretary, Jack Straw, downplayed the odds of war, placing them at 60-40 against. Blair recently urged U.N. inspectors be given "time and space" to do their job. And in comments on Tuesday, apparently in answer to Germany and France, he emphasized that the imminent threat of war may be, in itself, essential to avoiding war.

"The one thing that is very obvious," he said, "is that as a result of the military buildup and as a result of the determination to see this thing through, the regime in Iraq and Saddam are weakening ... and that is why we have to keep up the pressure every inch of the way."

Critics, however, worry that Blair is merely naive. And that assessment only highlights the difficulty he's had in making his case. "I think Blair's enormously frustrated with the debate on Iraq because he believes the evidence is clear," says Henderson. "But people expect high standards of arguments for doing something other than the status quo. And he hasn't managed to win those arguments yet. He hasn't managed the public debate."

Andrew Rawnsley, a newspaper columnist for the Observer, noted the odd disconnect last week: "The British are usually undaunted by the prospect of war, and Tony Blair is generally the most effective communicator of his political generation." Yet he's simply not been able to sell this war.

Even Gardiner, who considers Blair's hawkish stance on Iraq to be the prime minister's "finest hour," concedes Blair still needs to sell the public, perhaps with a prime-time televised appeal.

One week after his hour-long press conference, which was meant to bolster confidence, a Guardian poll found that support for war had dropped six points in just the past month, to a paltry 30 percent.

Experts suggest Blair's difficulties stem from an array of obstacles, beginning, says Henderson, with "a broad streak of anti-Americanism in this country" that's been reawakened by Bush's lone-rider cowboy persona.

Meanwhile, Britain's war critics, both in Parliament and in the press, are far less timid than their counterparts in America. Using the type of strident language that's rarely heard by elected U.S. officials, one on-the-record Labour Party chairman recently told the Telegraph: "We have no justification at all for a war on Iraq. The logic of the situation beggars belief. It is manufactured by George Bush, and oil is a factor."

And unlike Bush, Blair does not have an entrenched neoconservative movement like the one in the U.S. that's been beating the drums of war so effectively for the past year. Neocon hawks both inside the administration (Vice President Dick Cheney and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz) and in the political press (the Weekly Standard, Wall Street Journal) have been lobbying for war with Iraq almost since the moment the World Trade Center was attacked. They're convinced that toppling Saddam will not only make America safer but, after the regime change, also be the first crucial step in redrawing the entire Middle East.

"There's very little of that neocon culture here, or that messianic sense of this war," notes Kettle. "Nobody thinks we can redraw the map of the world. And Blair certainly does not talk about it."

Blair's Iraq policy does have the editorial support of Rupert Murdoch's bestselling newspaper, the Sun, along with other conservative voices in the British press, including the Times, the Sunday Times and the Telegraph. But even that right-wing support seems tepid. Writing this month in London's venerable conservative weekly magazine the Spectator, one guest columnist boldly declared: "There exists no legitimate reason for us to wage or threaten war against Iraq. Saddam Hussein poses no threat to us."

There is some good news for Blair as he tries to maneuver his way to safe ground. His conservative political opponents in the Tory Party remain in such a state of disarray that he has nothing to fear from their jabs. (Blair easily won his two previous elections.)

Instead, it's inside his own Labour Party that Blair has to watch for real trouble. Last November marked the first time as prime minister that Blair was subject to hostile interrogation from members of his own party, or backbenchers, during the weekly question-and-answer session with him. The topic was Iraq.

Today, approximately 130 of Labour's 400-plus M.P.s have signed a petition critical of any unilateral war with Iraq, while a recent survey of 74 Labour Party chairmen revealed that 89 percent of them opposed war on Iraq if it came without a U.N. resolution authorizing force. The chairmen also predicted thousands would desert the party if Blair lead Britain into war. Writing in the Independent newspaper this month, one Labour Party M.P. declared: "The Prime Minister may take Britain into America's war, but he will not take the party with him."

Some have compared Blair's simmering crisis to 1956 and the botched 72-hour battle Britain fought with Egypt over the nationalization of the Suez Canal. Back then Sir Anthony Eden lost the prime minister's post, punished for taking Britain into war without public support.

Still, Labour backbenchers owe Blair a lot and have for years showed remarkable discipline. Parliament watchers suggest one in 10 Labour M.P.s will stand by Blair no matter what he decides on Iraq, three in 10 are already opposed, and the remaining six of 10 are up for grabs. They're the ones who could ultimately decide the question of war. (Along with Attorney General Lord Peter Goldsmith, who may have to rule on the legality of Britain's fighting a preemptive war not authorized by the U.N.)

Indeed, the only thing that would cause Blair to back out of a war now, says Kettle, "is a revolt within his own party involving a major member of government."

That major member, most agree, would probably have to be Chancellor Gordon Brown, among the most powerful members of Blair's cabinet. During the 1980s the two men helped rejuvenate the Labour Party, with its now more moderate image, and today Brown is considered to be Blair's most likely successor. Once good friends, the two have their separate political camps and eye each other warily. Ambitious, Gordon clearly has his eye on the top job. While he recently did come to Blair's aid by publicly supporting the prime minister's hawkish position on Iraq, it came only after three months of relative silence, leading to some speculation he was trying to distance himself from Blair.

If, and it's a big if, Brown were to break ranks with Blair over Iraq either publicly or, more likely, behind closed doors, Blair's leadership would then be under serious attack, and the White House could lose its most important ally. "If Blair couldn't carry Gordon Brown, he'd be in real trouble," says Eric Shaw, a professor of political science at the University of Stirling in Scotland.

That's precisely why the United States has to move quickly on Iraq, says Gardiner. The longer the debate simmers, the more emboldened Blair's Labour Party opponents may become, and they may eventually challenge his leadership, which could throw into question Britain's role in the war. "Blair can't afford to be left hanging for months," says Gardiner.

It's clear the White House doesn't want to delay an invasion for months, which is good news for Blair. Still, there's a chance Saddam's reign won't be the only one decided by the war.

Shares