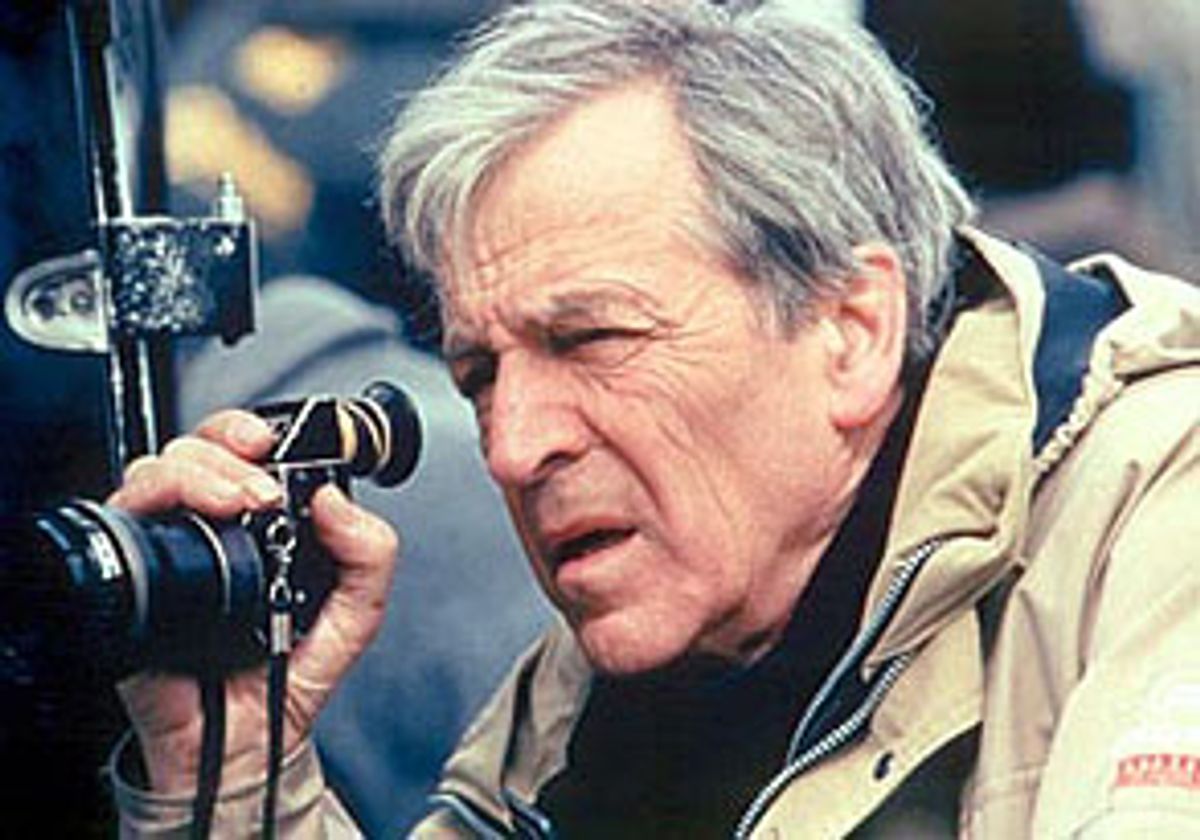

Costa-Gavras has been film's leading political dramatist since bursting onto the scene with "Z" (actually his fourth film) in 1969. That film, a docudrama about the assassination of a leading leftist by the military junta in his native Greece, set the template for much of the director's subsequent work. Costa-Gavras (the hyphenated name, by the way, is an abbreviated version of his birth name, Konstantinos Gavras) has documented the struggle between the government of Uruguay and leftist guerrillas in the early 1970s ("State of Siege"), the abduction of an American human-rights worker by Chilean death squads at the moment of a U.S.-sponsored coup ("Missing") and the war-crimes trial of a former Nazi official ("Music Box").

Although sometimes derided by American critics as an old-line Euro-leftist, Costa-Gavras has never shied away from a direct assault on authority or from staking out controversial positions. "A film contains a director's or writer's philosophy of life, so that makes it almost immediately political," he says. "In my films, because I've treated many themes that have rarely been treated by the cinema -- and I handle them in a personal way -- that makes them more political than others." With "Amen," his 19th feature film, Costa-Gavras, who will turn 69 in February, tackles yet another hot-button issue -- the complacency of the Vatican during the Holocaust.

You've said that your films aren't about the past but about the present, no matter what you're specifically depicting. What, then, does your new film about the Vatican and Pope Pius XII and his inaction during the Holocaust tell us about the present?

It is a metaphor about the present. It's about silence and indifference -- the indifference that happened at that time toward the Jews and the Gypsies in Europe. This is the same indifference we have today about other tragedies around the world. Like the state of Africa. Or the silence of the Vatican about the atrocities of various dictatorships in Latin America. All the dictatorships there were backed to some degree by the church.

Did you encounter any resistance at all in making "Amen"?

Very little. After it came out, there was criticism. There were letters from the Catholic Church, from the extreme right of the church. I didn't expect the criticism to be to the extent it's been, so aggressive. This was not a new story, it was based on Rolf Hochhuth's play "The Representative," and I relied a lot on David Wyman's book "The Abandonment of the Jews."

But I don't think about resistance to the film when I'm making it. I think about how I can tell the story, a better story, for the audience. And in the end, the surprise for me was that they attacked the film indirectly, by attacking the poster. It worked: The result was to create a kind of negative ambience around the movie. But then people saw it, and became quite attached to the movie.

How carefully do you consider the criticism?

I look first at who is criticizing and what they're saying about the movie. Their criticism on other matters, the rest of their behavior in life, makes them believable or not to me.

Does it surprise you that a religious institution deals with problems and criticism much in the same way a government or a corporation might? And that its followers defend it so?

Unfortunately no. They try to justify their silence by apologizing after the fact. They think that is sufficient. Most of the Catholic churches and the Protestant churches in Europe apologized for their silence and inaction during the Holocaust. Priests from the Chilean and Argentinean Catholic churches asked to be pardoned for not speaking against dictatorships in those countries. That was also the situation in Rwanda. Eight hundred thousand people were slaughtered in three months, hundreds per hour. We know very clearly today that the Catholic Church knew about it, and priests and bishops were close to the party behind the massacre. The point is to speak during the time that something is happening. They try to defend themselves by recognizing that they did something wrong, and by asking to be pardoned.

What hope then is there that people see the faults of those making the mistakes, and understand what's going on around them?

Well, it takes time, and they need to be educated. But it's not my role to educate people. I make movies, and I try to say what I think about some situation, like in "Missing" about the repressive regime in Chile at the time, or the assassination of an MP in Greece in "Z." The viewers have to decide for themselves how they should react.

But you must hope that your films will make people look at a situation differently, whether it's a political situation or something in their daily lives?

First, everyday life is politics. When I make movies, or others write books, or people direct plays, they're all political acts. An Italian historian once said something very true about the relationship between a socialist society and the cinema and history. He said that a film can bring a viewer into a historian's or sociologist's workshop. And from there, the viewer can decide what to think and which direction they will go. I try to make my films with that specific idea in mind.

Whether or not you've set out to make explicitly political films or not, that is the end result. What makes a film political in your mind?

A film contains a director's -- or writer's -- philosophy of life. So that makes it almost immediately political. In my films, because I've treated many themes that have rarely been treated by the cinema -- and I handle them in a personal way -- that makes them more political than others. I don't use happy endings, I try not to glorify any of the characters. So this could be one explanation.

There is a danger of coming off as self-righteous, though. How do you counter that?

The only way to do this is to be as sincere and as accurate as I can be with the real characters and situations I'm treating. When we finished "Missing," a lot of people jumped on it aggressively in the U.S. and said it was not true, they said it was anti-American. I knew it wasn't made up, I knew it was real. I had to wait nearly 10 years, but through official lines, finally we were told that what we had depicted was in fact real. If I wasn't sure that what I was showing was the truth, I wouldn't have made the movie the way I did. Most of the time there is some validation down the road. Art and cinema should be, and it is sometimes, ahead of society.

Is it the responsibility of artists today to inform us in some way about things happening in our world? I mean, you can argue that the news media isn't really doing all it should. Do the arts then fill the void?

Again, it's the role of art to simply be ahead of its time. Go back to the Greek tragedies. They were ahead of their own time, and even to some degree our time. Look at "Oedipus," it's still very modern. Of course, the media and those with power have to follow the dominant ideology. Let's talk about [former Chilean dictator Augusto] Pinochet for example. At the time, a lot of media outlets were defending Pinochet, saying he saved Chile from communism, and so forth. So there was a reason for that. But from what I knew of Pinochet and his regime, I saw them as bad. The dominant ideology was to protect, as much as possible, the regime against communism.

That's not so different today, is it, this impulse to protect a regime, a government?

We have a good example today. There's the example of terrorism. Everybody's against it, everybody. But go back, and look at which of today's chiefs of state were once considered terrorists. We can start in Israel, over to Africa to Latin America. Look at Arafat, he was a major terrorist for everyone years ago. And today people accept him as a leader -- even Sharon has said, in a way, that he accepts him as that. What I'm trying to say, then, is that the problem of terrorism has to be approached in a different way. It has to be fought, but it's important to study the reasons behind it. Terrorism can be reduced if political or economic or military actions are taken. This is an example of a general, accepted ideology.

Many of the themes in your films seemed somewhat at odds with some of the methods of production, and distribution; I mean, working on them in the Hollywood studio system.

Well, Hollywood's production and distribution methods have changed considerably in the last few years. The only cinema in the world that is made by companies without any state help is the American system. All the others, in order to exist and to produce movies with ambitious subjects, need some state support. The best country for this, no question, is France. But it's still very difficult.

Does the change in Hollywood reflect the interests of the general public in what they want to see? Are people not as engaged and as politically aware as they were in the late '60s? Maybe they're happy being indifferent?

That's a very difficult question. What comes first, what the audience wants to see or what the production wants to sell them? I believe it's a kind of education for the audience. If you give them big action movies all the time, far away from everyday problems, they probably will prefer to see that. But if you offered them different films, they'd go to see them. Of course it's the kind of risk the producers and financiers generally don't take.

What about for the filmmaker, the director? What, besides money, does he need to make films that are about more social and political themes, that are perhaps more difficult?

Well, they have to have a stronger eye on our society and our problems, instead of having an eye on succeeding and making a lot of money. It's a question of how you're willing to perceive our society. Make the film you're willing to make, it should be as personal as possible, and that's the most important thing, first. But a movie is a show; people go for pleasure, to laugh and to cry, to be moved, whatever the reason. The movie's not there to teach a lesson or to teach history.

Is that why you've made mostly dramatic features rather than documentaries?

Oh, yes. And with documentaries it's impossible to use the metaphor. A movie is a metaphor, through the story we tell, about other moments, other countries, other situations. Art is metaphor for truth. Documentaries are direct and deal directly with a subject.

And how do you deal with people who might say what you depict in a film is not true? How do you gain an audience's trust?

I just write what I know is the truth, or a concentrate of the truth, because to tell an entire story takes too long. I have two hours. The basic truth is there. When politicians or others are against it, all I can say is, wait and see. I can show them the books I've read, the papers I've read. When I made "Betrayed," for example, Mr. Buchanan said I was a European Marxist and that this would never happen in the U.S. Well, a few years later, you had the Oklahoma City bombing, and the people behind that were the same as the ones in "Betrayed." Or whoever it is that spread the anthrax scare more recently.

Again, I can understand that people are ready to defend a system or an ideology, because they are so convinced themselves. The most difficult thing in our society, and without education, is not to change our opinions, but to reevaluate them, to see if there's something wrong with our opinion.

Is there any institution, body of people, government, that isn't tainted, that has some moral and ethical authority?

There are many, sure. Even when we talk about the church. There are individuals in the church who have a lot of moral authority, and probably we should look much more to the individuals than to the institution (or guilds or unions or governments). There are millions of people in the world who have a moral and ethical position on something, they're writing about it, talking about it, and they're doing what their ethical philosophy dictates to them. And maybe we should listen more to these people than the chief or head of whatever. The situation isn't desperate, there is a lot of hope. Because if you go back to my generation, the kinds of discussions we have today you couldn't have when I was younger, and the kinds of movies being made, you wouldn't see.

Most of your films have a trial as a key element, as the means of achieving justice. Do you think this is still how justice is attained?

I believe in our societies there are two essential elements: religion and justice. Their reason for existing is to ensure human justice. Whereas institutions with power, democratic or not, they can move in different directions away from justice and they can very easily contradict themselves. So the role of religion, and of justice, through trials, is to balance the different forces in a society, to judge how the system works.

Does art flourish in today's world?

The role of art today, again, is to be ahead of the times, to try to criticize and to be very aggressive against the injustices in our societies. There's an extraordinary exhibition in Paris now on surrealism, the revolution of the cult of surrealism. You can see the surrealists went against the traditional ways of making art, and they changed the world. So that's the role of art. But more and more, art today is in the hands of political and economic powers. Both are trying to say that art is for art, it's not there to criticize or to be against. It's to be aesthetic. But art has to play the former role.

Shares