Ann Louise Bardach calls her obsession with Cuba “una enfermedad,” a sickness. Checking the wire-service news every day, exchanging gossip with friends in Havana and Miami, devouring each year’s harvest of Cuba-related books and movies — these are just a few of the illness’ symptoms. And while it’s true that others have been equally stricken — Ernest Hemingway being the most prominent casualty — few of history’s Cuba-philes have managed to contribute as much as Bardach has to today’s ongoing Cuba debate.

For the past decade, Bardach, now a columnist for Newsweek’s international edition, has been the most vigorous reporter on the Cuban scene. Everything from Cuba’s post-Soviet lunatic paradoxes to Miami’s tolerance for terrorism has been the subject of her investigative attention. In the midst of a world filled with intrigue and polarization, she’s always managed to be an equal opportunity critic. Leaders on both sides of the Florida Straits have learned to fear her efforts.

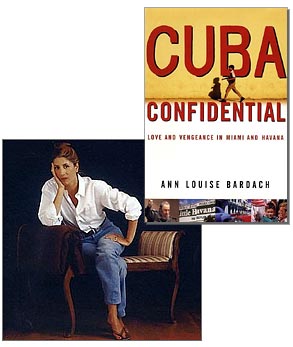

“Cuba Confidential: Love and Vengeance in Miami and Havana,” Bardach’s latest book, will likely continue that trend. Much of the reporting comes from Bardach’s old assignments, and scholars of Fidel Castro will probably find few new insights that haven’t already been discussed at length elsewhere. But the book is nonetheless fascinating and important. A family portrait of Cuban and Cuban-American dysfunction, “Cuba Confidential” offers both a scathing profile of Fidel Castro’s cold, cruel psyche and a comprehensive behind-the-scenes account of how exile leaders have ruled Miami with an iron fist. Even the section on the Elián González saga — a tawdry affair that few of us would like to revisit — comes alive again thanks to Bardach’s extensive reporting and critical insight.

With the advent of the increasingly popular Proyecto Varela referendum, how close is Cuba to democratic reform? Why are some leaders of the Cuban exile community so dead-set against change? How long will the U.S. embargo, or for that matter Fidel himself, last? And what will the future of a Cuba without Castro look like? Salon spoke to Bardach about her present feelings on the Cuba condition.

Oswaldo Payá, Cuba’s most famous dissident, visited Miami last week and received a mixed welcome. Exile leaders denounced him for legitimizing the regime while polls showed that 68 percent of Miami exiles support him. What do you make of Payá and his visit?

Let’s put it this way. The first person to make a dent into Fidel Castro, successfully, is Oswaldo Payá. This is the first successful organized opposition — but I don’t think you ever want to forget that Elizardo Sanchez and many other dissidents have paid big dues. But Payá has really gone to the mat with this one.

Jimmy Carter also hit one out of the ballpark. When he gave that speech on live Cuban TV in Spanish, he gave legitimacy to the Proyecto Varela [a peaceful opposition movement that has collected more than the 10,000 signatures required for a referendum on democratic reform in Cuba]. Remember, before Carter, the only people who knew about it were the people who signed it. After Carter, everyone on the island knows about it. It went from 11,000 people who knew about it to 11 million.

That speech totally trumped the Bush administration. To a Cuba watcher like me, the Carter speech was a really big event because it trumped the hardliners in the White House. They tried to sabotage Carter’s visit with that whole thing about Cuba having biological and chemical weapons. That was done to discredit him. They let Carter go [to Cuba] thinking, what could Jimmy Carter do? He’s a pathetic little peanut farmer from Georgia?

Who knew he was going to transform the Cuba debate? And on top of that, it gets Jimmy Carter the Nobel Prize. It gets Payá the Sakharov Prize [Europe’s most prestigious human rights award] — and I think Havel has nominated him for the Nobel. Now that’s not bad for 20 minutes in Havana. It just tells you what can happen with constructive engagement.

I’ve yet to hear, however, that more people are signing on to Varela now that it’s better known. Have you heard anything about the effects of Carter’s speech in Cuba?

Everybody knows about it. Let me give you a story. I wrote an editorial about a person involved in this. It talks in veiled terms about a friend of mine who was going to sign it. This is a person who was very involved in the government, at the very top. And you have a person like this saying that the Varela Project is the most important thing to happen in the last decade and [this person] is desperate to support it. This is such a telling anecdote. This is a person who was making explosives to export the Cuban Revolution around the world. When people like that, on this level, are ready to support it, then discontent, at varying degrees, exists from top to bottom.

What do you make of the exile leadership’s decision not to support Payá?

Well, in fact some of the leadership did support him, and it really shows the split that I talk about in the last chapter of “Cuba Confidential”: how serious this is going to get. The fact that you now have the [Cuban American National] Foundation supporting Payá and the polls show that 70 percent of Cubans in Miami support him, but then you have Lincoln Diaz-Balart and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen [South Florida’s Republican representatives, both of them Cuban exiles] saying he’s illegitimate because he’s part of the whole Castro government deal.

I don’t know if you know this, but they were pressuring the administration to disavow Payá and actually criticize him when he went down to Miami on May 20 last year. But Bush didn’t do that; he in fact embraced [the project], which stunned me. He gave a thunderous anti-Castro speech down there, but he embraced the Proyecto Varela. This must be what they call a knife in the heart — un puñal en el corazón, as they like to say dramatically — for Lincoln and Ileana. And you can see that this is a big problem. Even the famously cowardly publisher of the Miami Herald has embraced Proyecto Varela.

Remember that the Varela Project is Catholic based. So you have a lot of the tradition of Augustine and a lot of the Jesuit liberation theology in this. And of course, that’s a great way to deal with Castro because it’s hard for him to get a handle on that one. It’s very brilliant. And I really think that Lincoln Diaz-Balart and Ileana, they shot themselves in the foot this time.

The problem with Lincoln and Ileana is this: They are both mentored by their fathers — two men who are deeply embittered hard-liners who basically will not be happy unless Fidel is hanging by his heels à la Mussolini in Calle Ocho. That is their bottom line. It’s about vengeance, which is why I wanted that subtitle on my book — “Love and Vengeance in Miami and Havana.” It’s all about vengeance. It’s not about, let’s get this over with, let’s get this moving, let’s get a good solution, let’s get as much as we can. It’s about, we must achieve some level of vengeance here.

And Fidel, as you point out, is the same way.

Absolutely. Because they’re all coming out of this machista ethic. That’s the whole tragedy of the Cuban debate: Cubans leave Cuba but they take Fidel Castro with them. The politics of denunciation, which were to a large extent created in the revolution with CDRs [Committees for the Defense of the Revolution] and snitching and such, was exported to Miami. You have the same process. You have the big three radio stations doing the same thing, denouncing people to keep them straight, functioning as Big Brother of Miami.

One of the reasons that vengeance is the response you get from so many older hard-liner Cubans is that Fidel Castro has a way of emasculating people. His policies, particularly in a machista culture like Cuba’s, make people feel emasculated and humiliated. That’s why they want a pound of flesh afterwards.

If you stay in Cuba a long time and hang out with Cuban friends, you see that what they go through on a daily basis is humiliation: to have to beg for this, to beg for that. You try to get in this hotel or that one — it’s a humiliating cycle and it’s never really been explained, even though they do not have the privations of, say, Guatemala or the atrocities we saw in Chile or Argentina even.

Castro has kind of institutionalized begging. Even though you don’t have the death squads and the disappearances and the torture, when you make people feel like they’re beggars, that’s where you get that kind of rage. I wish I had spent a bit more time writing about that.

The level of rage in Miami, however, seems to be diminishing. Polls show that an increasingly high percentage of Cuban-Americans, for example, no longer support the U.S. embargo. And as you mentioned, there’s been a split in opinion over Payá. When did this shift get its start?

You cannot underestimate how things unraveled after Jorge Mas [Canosa, the head of the Cuban American National Foundation] died. You basically had Mas holding things together with the force of his personality. Of course, he had a huge amount of charisma and no one crossed him. From the minute he died, it’s been a free-for-all.

I actually think that Jorge Mas never would have gambled on Elián González. He would have right away sized that one up and walked away from it. Trying to tell the American public that a father should have his son taken away because he lives in Cuba is not really winnable. I don’t think Mas would have done this out of any virtue or anything. I think he would have looked at it and said, what would it take to take the kid away from the father? And he’d say, we’re not going there.

I think that Jorge Mas Santos, the son, doesn’t get nearly as much credit as he should. It takes no courage, no bravery, to rail against Fidel Castro in Miami. That takes nothing. But it takes a lot of guts to say, let’s try this a different way. Jorge Mas Santos has been willing to do that, even in the shadow of his father. People forget that he fought very hard to bring the Latin Grammys and all that it meant to Miami.

How do you think the Bush administration will handle this shift, given the importance of Florida to national politics?

Somebody who is very close to this White House said to me at a party recently, “OK, you’re the expert on Cuba: What do I tell this administration about how to get rid of this turkey?” How do we get rid of this embargo and get it over with?

This is from an ideologue on the right. This is before the 2002 election in October. And I said, if I were George Bush and I were thinking about this, I guess I would do whatever I had to do to get my brother elected and hold on to my base for the next election. Then I would cut them loose.

Because if you don’t cut loose on this embargo, you’re hemorrhaging every day. Every day you’re losing people in the Senate and the House. If they keep going against this, they’re going to drag this turkey to the next election. And how much time and how much capital and how much money do you want to use to hold on to this thing that there’s no support for among the general population, or our allies? There’s even an erosion of support every day in South Florida.

Let me be clear: I’m not against embargoes. I think sometimes embargoes work. We have to thank an embargo for the shift in South Africa that gave the disenfranchised the right to vote. Sometimes embargoes work. I think you can give an embargo around 10 years; if you’re really patient, you give it 15 to 20 years. You don’t give an embargo or any policy 43 years without meeting your goals or at least some of your goals. All we keep doing is tightening it and we’re getting less and less and less.

At some point you say, this is insane, we’re not achieving anything. The U.S. has to step back and say, OK, we lost, he won, how do we shift this? There has to be strategic, cool-headed thinking about how to bring democratic reform to Cuba and not about achieving vengeance and getting a pound of flesh.

But given the circumstances, do you think it will ever happen? Do you think we’ll see an end to the embargo, say before the next election?

They’ve got their hands really filled with North Korea and Iraq. How can they waste capital and time on Latin America and Cuba?

I think what they’ll do is give lip service to the [old guard]. They’ll say, “Oh God, in our heart we feel for you,” and they’ll keep pushing them to the side, giving a wink and a nod to the Republican free-traders who are the majority and who just in principle want to trade with Cuba. They’ll let them put together a veto-proof thing and they’re going to attach it to some bill and be over with it. Remember, it was Kissinger in 1976 — a Republican — who was ready to toss our Cuba policy out.

What do you predict for the next decade in Cuba?

The central player remains Fidel Castro. But Fidel Castro is nothing if not a survivor. He’s eaten 10 American presidents for breakfast. He’s chewing on his 10th president. He will give ground only based on what he needs to give ground. He can only save his bacon with tourism. And the nature of tourism is that you have to let foreigners come in. So he has to graduate tolerance and openness — a loosening of the belt.

0n the other hand, I must say, I thought I’d seen and heard it all in Cuba. But when Jimmy Carter left after that big speech and everyone knows about Varela and suddenly Fidel Castro smashes through that referendum to make [socialism] permanent: That was such spectacularly bad behavior even by his standards. I just thought, the sheer insult to Carter! I just thought he would wait awhile and do it in a less obvious way. It just showed that he so desperately needed to show who was in charge.

I remember the first time I met Fidel Castro, I said to him, why don’t you do something like Holland and Sweden and just do some kind of socialism? You lost the Russians; why not can the hardcore communism? You don’t have the money to pay for it anyway, so make it a mixed economy, which of course it is now.

But he’s afraid of losing control. What he lives and breathes is the fear of what happened to Gorbachev, who he — actually in the film I just saw [“Comandante,” Oliver Stone’s new documentary] — describes as this well-intentioned man who destroyed his country. That’s what he believes; that perestroika before glasnost is what doomed Russia. He was in there until the bitter end trying to convince Gorbachev not to open it up.

The collapse of Russia haunts Fidel Castro. It just made him become more convinced that he couldn’t yield. But as we see, he yields every day, as needed.

When I first started doing this 10 years ago, all the smart people, the really smart disenchanted nomenklatura, the dissidents, all said, you don’t understand: It’s really simple, Fidel can’t stay in power without the embargo. I said, don’t be ridiculous, all he does is rant every day about the imperialistas. And they said, you don’t understand.

And then sure enough, as I tried to show in my book, at every critical juncture, he pulled the plug on ending it. Just look at it: Who is the winner from the U.S. embargo? There’s only one winner here, and it’s him.

What about after Castro? What do you think will happen?

I don’t see anyone having an appetite for bloodshed. The only people who have an appetite for bloodshed are a few people in Miami. And the thing about them is, it’s never going to be their blood. I think it’s very interesting that Lincoln Diaz-Balart criticizes Oswaldo Payá for selling out to the regime, but he’s not willing to be in Cuba and go to prison. I love how they like to criticize people from their nice homes in Miami — people who have been in solitary confinement. It’s amazing to me. The hubris! They’re sitting there in Miami Beach and criticizing people who have really made a difference, like Elizardo Sanchez, who spent 11 years in prison. It’s outrageous.