Talking about the documentary "Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary" in aesthetic terms entails talking about what isn't there. Cut down to 90 minutes from 26 hours of interviews with Traudl Junge, one of the women who worked as a private secretary to Adolf Hitler, the film consists entirely of medium shots of Junge as she recounts her experiences working for Hitler. There is no music, no newsreel footage, no archival photography. The directors, André Heller (who conducted the interviews) and Othmar Schmiderer, don't allow anything to distract us from Junge.

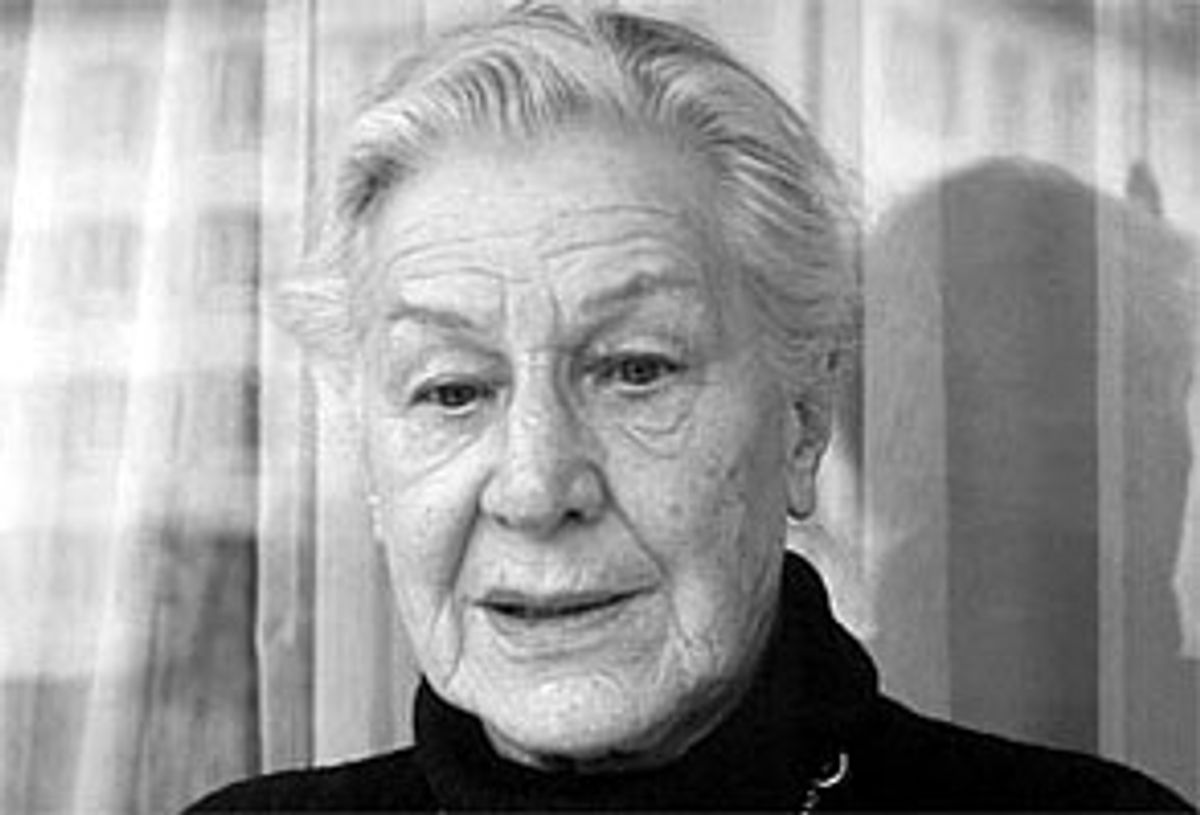

Once or twice we see her watching a videotape of one of her interviews, not for any overtly cinematic effect but rather for her to annotate or expand what she has already said. The drama of the film is in the story Junge has to tell but, more important, in her reckoning with the consequences of her history. The subject is as much Junge in the present (she was 81 when the interviews were conducted in the spring of 2001; she died last year, the day after the film premiered at the Berlin Film Festival) as what she witnessed during the early 1940s.

What I'm saying is that any judgment on "Blind Spot" is very much a judgment on Traudl Junge. The film is not what you may have been led to expect -- and what I expected walking in. It is not another participant in the Nazi terror denying knowledge or responsibility, pretending to be shocked. Junge does claim she did not know the extent of what was done to the Jews until after the war, and because of the weird, removed circumstances she was in, it's not hard to believe her.

A dignified old woman with steel-gray hair worn swept back and a taste for colorful scarves worn under sweaters and jerseys, Junge is serious and focused and largely self-effacing. She sketches in her own story quickly, as if it were of no particular importance next to the gravity of the events she describes. She grew up in Bavaria, the daughter of a divorced mother who provided for the family by working as a maid for Junge's bossy grandfather. Junge harbored hopes of becoming a dancer but also knew she would have to work. Family connections got her a clerical tryout for a job as secretary to the Führer and, in 1941, she went to live and work in Hitler's bunker compound.

It's probably necessary to make a few particulars about Junge clear at this point. Her family, she tells us, was apolitical. She was never a member of the Nazi Party. Working for Hitler, her job was to take dictation of his speeches and private letters. Military and government matters were not discussed in her presence. The only mention of Jews came in the inevitable lines in Hitler's speeches about the poison of "international Judaism."

If that sounds awfully convenient -- if it seems to echo what we've heard from the mouths of so many other Nazi officers and functionaries and hangers-on -- none that I've seen interviewed have anything like Junge's compulsion for self-examination. She is not claiming that there was no way for Germans to know what was going on, she is damning her own obliviousness. The first words we hear her utter in the film are about how, even at 81, she finds it impossible to forgive the naive, uninformed girl she was. We all look back at our younger selves and cringe, but for most of us, the blind spots of our youth don't encompass anything near as unthinkable as the events of Junge's youth.

But the blind spot of the title refers not only to her youthful ignorance but to the closed world of Hitler's bunker. Hitler, Junge says, was so caught up in attaining his ideals that human life simply didn't matter to him, or was an acceptable price to pay to achieve his dreams. In the bunker, where Junge was exempt from the shortages of the war and from the realities ordinary Germans encountered, the talk, particularly Hitler's talk and the chatter of those around him, would be in grand terms rather than specifics. Purifying German culture -- yes. Exterminating the Jews -- no. What comes through clearly again and again in Junge's testimony is that she was in the perfect place for an ignorant young woman to continue to be ignorant, even to be encouraged in that ignorance.

So the unsparing tone she brings to these memoirs (the film marked the first time she had talked publicly about her experience), her struggle to understand her foolish younger self and her impatience with herself when she lingers over a trivial detail of bunker life are her revenge against that ignorance. In its singular way, "Blind Spot" is an unflinching portrait of a commitment to intellectual and moral growth, even if it means cutting away the ground beneath your own feet.

"Blind Spot" is consistently interesting without feeling essential until, in its last half-hour, it becomes utterly compelling. Junge's account of Hitler's last days in the bunker may well be the most vivid, and the last, we will ever hear. (Have any others who emerged alive from the bunker told their stories?) Time and time again she talks of what a strange atmosphere it was, as if trying to convince herself that it actually happened.

"Bosch," she declares it at one point, and there is a temptation to see what she is describing as the most grotesque black comedy imaginable: the ritual declarations of loyalty to the Führer; the officers unable to carry out Hitler's command to kill him so he wouldn't fall into the hands of his enemies. All this, combined with Hitler's last-minute marriage to Eva Braun and Goebbels' wife poisoning her six children (the only tears Junge sheds in the whole film, and they are brief, are for the dead Goebbels children).

It's the sheer grotesque mix of events, all of it laden with a heavy Teutonic sentimentality, a kitsch notion of tragedy, that repulses Junge -- and us -- as much as anything else. She stayed, even when Hitler said she should go home. As she says, where else was there for her to go? (She, and other German women, also had a legitimate fear of being raped by the advancing Russian troops.) There's something oddly fitting in the hell Junge describes, as if even Hitler finally came to feel the derangement he had brought to every particle of German life.

The film comes to a conclusion with a brief outline of Junge's life after the war. She was captured and imprisoned by the Russians, went home to Bavaria, was then imprisoned by the Americans for three weeks and was finally declared "de-Nazified" in 1947. After that, she worked as an editor and science journalist, living in a one-room apartment in suburban Munich from the '50s onward. Like the other details of her life, this seems unimportant to Junge. Nothing, in fact, seems important to her except the moral and intellectual interrogation she puts herself through in the course of the film. Despite its title, "Blind Spot" is a convincing portrait of one woman's restless determination finally to see.

Shares