Veteran speech consultant and communications expert Richard Greene doesn't mince words when it comes to criticizing President Bush as a public speaker. "He is the least articulate president that I've ever seen or I've ever listened to," Greene told Salon, just before Bush's State of the Union address on Tuesday. "He is a horrible communicator."

But sitting in front of the television watching Bush address Congress Tuesday night, Greene was pleasantly surprised by what he saw. He says the speech was the president's best ever, and Greene should know. The author of "Words that Shook the World," a 2002 book that assembled and analyzed 20 speeches he identified as the best of the last 100 years, he's been an advisor to high-powered clients in the corporate and political worlds, from Princess Diana to presidential candidates. And he's studied Bush's oratory: Before the 2000 election, he informally advised campaign strategist Karl Rove on the many and profound weaknesses in Bush's performance on the stump. He's even met Bush a couple of times.

Perhaps, in such speeches, most of us hear what we want to hear, and believe what we're predisposed to believe. The New York Times called Bush's speech "his strongest effort yet to convince reluctant allies and anxious Americans that war with Iraq may be unavoidable." A poll by CNN, USA Today and Gallup showed an overwhelming 84 percent positive response to the speech. Yet Bush critic Maureen Dowd thought it fell short. "At a moment when Americans were hungry for reassurance that the monomaniacal focus on Iraq makes sense when the economy is sputtering, Mr. Bush offered a rousing closing argument for war, but no convincing bill of particulars," Dowd wrote in her Times column Wednesday.

Greene admits that Bush didn't deliver the ultimate case for war with Iraq -- but he says that's not what the speech was meant to do. "Here's the great truth about selling a case, whether it's front of a jury or in front of the world like Bush was Tuesday night: If you like the messenger, if you feel a connection to the messenger, you will be receptive to the message. And his job last night was to make people like him and be more receptive to the message that was to come." Bush pulled it off, Greene says.

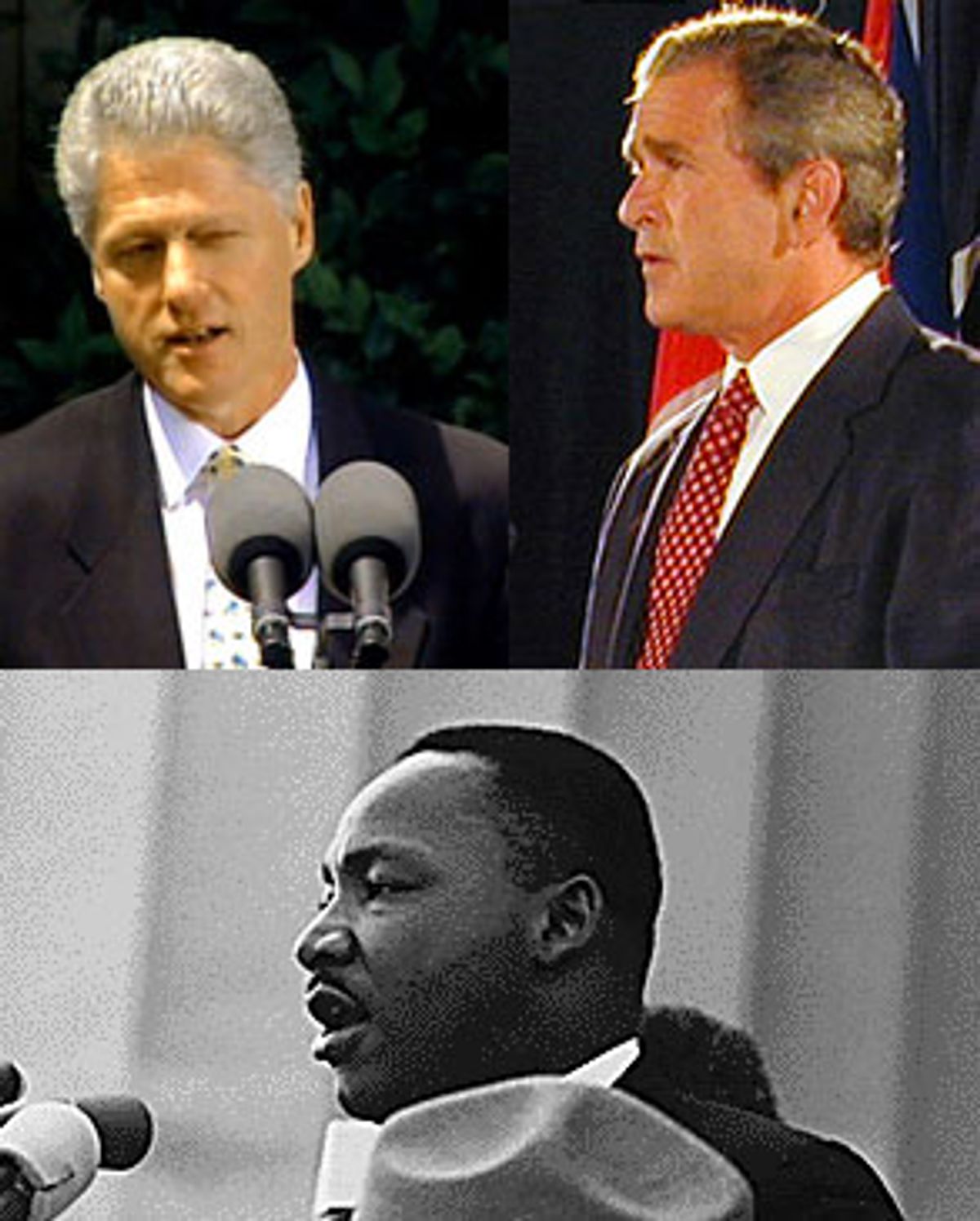

It is surely a controversial conclusion, and Greene himself is surprised by it. In interviews before the speech and after -- our abridged conversation follows below -- he was a stern critic of the president, both as a speaker and as a policy-maker. But when assessing a leader's ability to persuade, he has ample grounds for comparison. In assembling his book, he reviewed hundreds of speeches by dozens of speakers. The Rev. Martin Luther King, the slain civil rights leader, was the best of them all, Greene says. The late Barbara Jordan, the first black woman elected to Congress from a formerly Confederate state, followed King. Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and Albert Einstein were also at the top of his list.

Bush, in his State of the Union address, did not reach that standard -- but Greene insists he came close.

Historically, how important is the State of the Union speech?

I think every State of the Union speech is important for different reasons and in different degrees. I think in peacetime, with no major issues going on, it's a critical opportunity, mainly for the president, to create a connection to the American people. It's the only time in a year that we have a one-on-one, face-to-face conversation, and if it's done well, it feels like a conversation. If it's done poorly, it feels like a speech. That is an unbelievably important opportunity, even in the most calm of times. In times where there is great doubt about the individual -- his competency, his capability, his direction as a leader, like there was when Clinton gave his State of the Union speech around the time of Monica Lewinsky -- these are very important times to reestablish and reconnect, as Clinton did so well in that State of the Union following his impeachment. And certainly, in times like this, when the country and the world are poised to move in a very dramatic direction, we are all looking at not just the word, but we are looking very much at the level of confidence and certainty surrounding those words from our leader during the State of the Union. It cannot be overstated, the amount that those nonverbals -- of confidence and certainty and resoluteness, or lack thereof -- will affect the poll numbers immediately following a speech like this.

So then: Go back to the moment after the curtain fell on Bush's speech Tuesday night and tell me what your first reaction was.

I was quite impressed. For George Bush, I think it was an A performance. Relative to other presidents, like Kennedy, Reagan and Clinton, I would give it a B+. I think that there are a number of different George Bushes giving that speech. There's the George Bush who's clearly reading the teleprompter and not being a natural orator and having that show. I think that there is a George Bush who is still uncomfortable as a speaker and as an orator and in the beginning especially, I found that he was quite nervous -- nervous and scared. But as the speech progressed, and it was written in such a skillful way to build his connection as a compassionate and emotional and sober and presidential president, I felt that he ultimately reached a crescendo of connection with message and audience that was by far the best oratorical moment of his presidency.

How could you tell in the early part of the speech that he was nervous and scared?

His facial gestures were forced and stiff, and he does what he often does when he's uncomfortable, which is that he over-enunciates and over-extends his lips. And he forces his head forward and gestures not with his whole body, in a natural, relaxed way, but in an awkward, forced way, with his head bobbing forward and his eyes and lips making somewhat forced and dramatic movements. It's more subtle than it used to be, and I'm sure he's received quite a bit of coaching on this, to smooth out the rough edges, but it's still on close examination obvious that he's not yet in his comfort zone when he started the speech.

You seem to be saying that a key element of Bush's success was the emotion conveyed in his presentation. But Maureen Dowd, in the New York Times Wednesday morning, had this take: We were all waiting for a compelling argument on Iraq. This was the time, this was the place -- and he came up short. He said nothing new. He didn't deliver any new evidence. Is there a risk that if we give too much emphasis to the delivery, we'll give too little to the message, or the lack of message?

Well, here's the great truth about selling a case, whether it's front of a jury or in front of the world like Bush was Tuesday night. If you like the messenger, if you feel a connection to the messenger, you will be receptive to the message. And his job last night was to make people like him and be more receptive to the message that was to come. I don't think that they even wanted to use the speech last night as the forum to put out new evidence.

People who listened to the speech, both in our country and overseas, very much have Iraq on their minds. Do you think that many of them, after hearing the speech, would be moved from the antiwar column, or the undecided column, into a place more favorable to Bush?

Let me back up and say that I agree with Maureen Dowd. Personally, I do not think that Bush or the administration have made the case yet. I think they have come incredibly short on establishing a rationale on the question of "why now?" I mean, this guy has basically had all of this stuff and has been doing all these bad things for 11 years or more. So why now? Why should we stir up the hornets' nest? The ultimate question that I have not heard answered is: By attacking, don't we in fact encourage a madman to do something that he may or may not have been willing to do? I see a great argument against going in -- that if he has these weapons, they are probably defensive weapons, and only going to be used if he is fact going to be attacked? It's a logical flaw. And there was nothing in his speech that answered that.

But again, I return to my basic point: What he did Tuesday night was create a warmer, friendlier George Bush image for the rest of the world. He made a lot of progress in changing the reputation for those people who were watching around the world, of him being this loose-cannon, wild Texas cowboy. That was a huge step forward for him. Now, the administration is still going to have to sell the case. And I think they were very smart to put the ball now in Colin Powell's court, because he in my opinion is much more respected and has much more credibility in the foreign arena than George Bush. Better for him to come up with the hard evidence.

You've hit a number of points that can determine the success of a speech. Language, the emotion that a speaker brings to the speech, the importance of the historical moment at which the speech is made. Tell me, generally: What makes a speech great? What separates it from the routine and the run of the mill?

The first thing is a lasered message. One of the mistakes that so many people make when they make a speech is that they try to bring in the kitchen sink and throw two, four, seven, 10, 15 points out there. By the end of the speech, you have no idea what the theme was.

So when John Kennedy says, "Ich bin ein Berliner," and then he says it again at the end. And in the middle of the speech, he goes, "The Russians say, blah blah blah. Let them come to Berlin!" And he hits that theme four times in a row. And FDR's "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself." And Lou Gehrig's "I am the luckiest man on the face of the earth." And John Kennedy, "Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country." Churchill, "All I have to offer is my blood, toil, tears and sweat." Martin Luther King, "I have a dream." The speeches that survive are those that have an identifiable theme often -- often -- marked by what we would refer to now as a sound bite.

The second important thing is that in the giving of the speech, one has to communicate with not just the words, but also the other 93 percent of human communication, which is voice tone and body language. There was a study, a somewhat controversial study done in 1968, that indicated that words communicate only 7 percent of the overall impact of a speech or any communication. And determine only 7 percent of do you like someone or not like someone? Trust someone or not trust someone? Feel comfortable following or voting for that person, or not comfortable? And 38 percent of that result is communicated by the tone of your voice. Fifty-five percent is communicated by body language -- how you stand, what you do with you facial muscles. What you do with your arms. Things that George Bush does not do very well at this point, though he is getting better. That 7 percent, versus 93 percent non verbal, explains why, with the same team of speech writers at the White House for eight years from 1993 to 2001, Bill Clinton and Al Gore would give speeches with the same administration message, the same quality of speech writing, and a completely different result. Al Gore would bore people to tears, and Bill Clinton for the most part would inspire people with very much the same words.

The third thing is a little more complex. Human beings actually speak four different neurological languages every time they open up their mouths. We have the visual language, which is very dynamic and high-energy, I call it the Robin Williams language. It is critical for having an audience be filled with energy and pay attention. The second language would be called auditory. How do put what we see and what we feel into words that people can then understand -- a story line, a sense of beginning, middle and end, a sense of literature or drama. This is an area where George W. Bush has had very, very little competence. That part of his brain, for whatever reason, has not been well-developed. Some people assume it's because he's not very smart. But that is not necessarily the case. It could be, but it's not necessarily the case. The reason we assume that is because most people in business and politics are much more glib and articulate than George W. Bush. In my opinion, he is the least articulate president that I've ever seen or I've ever listened to. And following right after one of the most glib and most articulate presidents -- in my opinion the most articulate that we've ever had, which would be Bill Clinton.

Then we go to the third language, and that's called auditory digital, which is the ability to translate what you see and what you feel and to use facts, details and a depth of analysis that will in fact provide a foundation for soaring rhetoric. You can't have a speech that works if it's just fluff and inspiration. There's got to be some gravitas and some depth and some details that will ground it and support the emotions that are trying to be triggered. But the most important language is what we call kinesthetic, and it is a combination of the earthier, more sensual senses that we have -- touching, tasting and smelling. These operate at much lower frequencies. I call it the Barry White language. It's the "Ooooohhhhh baaaabyyy," taking 15 seconds just to say those two words. Where Robin Williams, in hyper-speed, might say it in a half-second or a quarter-second. This is where and this is why Bill Clinton was elected twice and survived his own foibles to the extent that he did. Because of his ability to --- and it became a buzzword in describing what Al Gore did not do -- his ability to connect. We may not -- if we're focused on seeing something or hearing something, we may not be consciously aware of it, but our body will receive it massively.

This is the language that in a movie causes somebody to cry. And this bit of information is worth unlimited amounts of money to anyone in sales. This is the language where many people make their decisions one way or another -- whether to vote for someone, whether to buy something or to go into business with someone, or even to go out with somebody. How does this idea feel? How does this speech make me feel? How does this person make me feel? You look at the details of what they're saying, and there may not be a lot there. But if the person is making the audience have a certain feeling, that's many times going to rule the day.

Let's talk in more detail about George W. Bush. You did include one of his speeches in your book -- the speech he made in the aftermath of Sept. 11. Where does he fit in the pantheon of great speakers of modern times?

We were very close to finishing the book when Sept. 11 happened, and in fact it was going to be the 20 greatest speeches of the 20th century. And then Sept. 11 happened, and George Bush, prior to that moment, would have probably been on an actual list that I would've made out, the last person on that list that I would even think about including in a book about the 20 greatest speeches. He is a horrible communicator. And really operates from maybe one and a half or maximum two of these languages. He has no capacity on his own to communicate in the auditory language that I referred to. His language to translate what he sees and what he feels into complete sentences and complete flowing paragraphs is almost nonexistent -- and surprisingly so for someone who's president of the United States, or even someone who's a governor. His capacity, his intellectual curiosity and his capacity to refer to and to integrate details and facts and a depth of analysis in his ad libbed communication, is again, almost nonexistent. And again, that does not mean he's not intelligent. That means to some extent he's been lazy in the development of those parts of his communication repertoire. He could be the smartest guy on the planet, but it doesn't many times sound like that because of his lack of competence in those two areas.

Where George Bush is in fact a very talented communicator and orator is in the area of the kinesthetic, the area of emotion. George Bush's training as an orator in a very real sense, and I'm not making this as a joke, came from his experience as a yell leader at Yale [athletic events]. If we remember back to right after Sept. 11 when he was in New York, it was almost eerie. Here's a guy who was a yell leader at an Ivy League college who is now president of the United States, standing up in front of a group of people with a megaphone, and rallying them as if it were at some sort of a football game, to be strong and to stay strong and to keep being hopeful -- all the things he would do at a football game, but instead of it being at his university, it was the country and the world. This is an emotional guy. This is a back-slapping, "c'mon, let's all pull together" guy. This is a round-em-up cowboy kind of guy. So when he combined those two things -- let's round up the bad guys -- you know, it was very Texan. His ability to see the world similar to the way Ronald Reagan did, in black and white, with very little gray, in good and evil, with very little in between, allows him with that simple world view, to be a yell leader without complication.

One of the problems with people who are auditory-digital and see a lot of grays in their world view, like Jimmy Carter, who was a Ph.D. in nuclear physics, is that you lose track of the fact that human beings need that simple lasered message. Ronald Reagan was also terrific in simplifying complex things. The entire Cold War -- the entire Cold War -- could be summarized by Ronald Reagan in 1987 standing up in front of the Berlin Wall, saying: "Mr. Gorbachev, tear ... down ... this ... wall!"

That simplicity and directness and laser-ness of message is one of the things that makes a great leader and a great speech. And in his post-Sept. 11 speech, Bush and his very excellent speechwriter, Mike Gerson, were able to translate all of these qualities that George Bush had -- this simplicity, this simple worldview, this round-em-up-cowboy sort of quality that Bush was obviously comfortable with, and this yell-leader quality that Bush was clearly very comfortable with, and put them in an extremely well-worded, beautifully crafted speech which I, as much as I didn't want to, felt was worthy of being included in this book.

You talk about the need to develop a laser-like message and the phrase that comes to mind when I'm thinking of George Bush is "axis of evil." Do you think that was a success, and that that speech was a success?

We now know that [phrase] was his -- that he changed that from the "axis of hatred." It was originally going to be "axis of hatred," but the information that I've read lately was that he changed that. And that one change -- "axis of hatred" to "axis of evil" -- was indicative again of his worldview, this very black-and-white world view that he has, that people in more mature and sophisticated parts of the world, like in Europe, have a hard time with. This one change has caused him to be criticized and America to be criticized heavily. "Axis of hatred" would've been fine. "Axis of evil" had the effect, in my opinion, of polarizing the world in a very unfortunate way.

Is it possible for somebody with Bush's nature and experience, his skills and deficits, to get better?

[Chuckles] People ask me that all the time. "If the president called you to help him, would you?" And the truth is, I would -- how do I put this? Before he became president, I had a couple of opportunities to spend some time with Karl Rove, and I did in fact share some performance tips with Karl Rove, some of which he seems to have implemented.

Such as? Can you be specific?

[Twelve-second pause] You know, out of respect to that relationship and the fact that he is now the president, I don't feel comfortable going into detail with that. But I can talk generally. I think, let's put it this way: When someone, and this is not specifically the advice I gave -- one of the reasons Bill Clinton was respected as a communicator and an orator was his posture. Bill Clinton has one of the best speaking postures of anyone who's ever spoken at a high level. He stands very tall, the shoulders are up, very straight and tall. And he gestures, while keeping his body still, he gestures with his hands appropriately, in a conversational, relaxed way, very much connected to his emotions and his feelings. In analyzing Al Gore during the 2000 campaign for television and newspapers, I actually ran across a time when Gore was saying, "We absolutely must move forward," and he was pointing 90 degrees off to the side. [Laughs] "And we must now come together!" -- but his hands were going apart. I showed this on TV and everyone cracked up. That's the reason he lost the election.

He was not connected, on a feeling level, with what he said. I would've suggested to Al Gore that he talk about the environment, because he clearly has a deep passion for the environment. And yet, because we're now in an era of polls and poll-driven sound bites, he was clearly told that was not an issue people cared about and he shouldn't go there. But then we have [Arizona Sen.] John McCain, who was trumpeting an issue that every poll says that no one understands or cares about, at that time, which was campaign finance reform, but because it was authentic passion, his authentic passion about campaign finance reform, even Democrats here in California fell in love with John McCain. If Al Gore had been more connected to his authentic feelings, he would've more than made up for that 537 votes in Florida.

Back to Bush. One of the things the president does that is tremendously undermining to his authority as a speaker, is -- he's doing it less now, but he does this thing I call "the duck head." He makes his points by forcing his head forward exactly like a duck does. I remember in the debates, he says: "It's fuzzy math!" And he was so emphatic that he forgot to use his hands to gesture and only used his head. And so you'd see this head bobbing back and forth. Any time someone uses their body language like that, they lose credibility and they lose authority. So could I help George Bush? Yes, I think he's getting better. I think he's beginning to own more, as every president does, a sense of gravitas in his speaking, which he did not have when he was governor of Texas. I think his ability to communicate emotionally and powerfully seems to have grown because there are emotional issues to deal with. His ability as a speaker when he is talking about economic policy or talking about certain aspects of domestic policy which do not involve emotion, and good and bad, and right and wrong, has been unchanged. He is a horribly ineffective communicator when dealing with more detailed topics, either foreign or domestic. And what people see as his growth as an orator is in large part due to the fact that he now is getting softballs. He now is able to speak on these big right-and-wrong, good-and-evil, let's-go-get-the-bad-guys topics which are right in his wheelhouse.

Most of all, what I would suggest to him, is -- and this is something that would be up to him to develop or not -- he will have reached a real ceiling in his ability to grow, especially in the extemporaneous and ad libbed communications, unless and until he develops more of an intellectual curiosity, that capacity I understand John Kennedy had, and that capacity Bill Clinton had, to be fascinated by a particular issue and to dig deeply into the substance of that issue. That intellectual curiosity that Albert Einstein said was the most important thing for any scientist and any human being seems not to be in great supply with George Bush. Without that, you can never have the passion and the details of that passion that drive great communication that are not written by other people.

You've suggested that the State of the Union is an opportunity for a president to have a conversation with the American people, and with people overseas as well. Obviously, this speech comes at a crucial juncture in modern history. Did Bush make the most of the opportunity?

You know, he really did. The big strategic decision, as to voice tone and body language, was: Do we come off strong, powerful, we're-going-to-go-in-and-eradicate-evil-in-the-world, with a Texas machismo and bravado, or do we do it more in a Bill Clinton-esque, I-feel-your-pain, softer, more kinesthetic way -- that touchy-feely human language? Do we come in visual with lots of energy and dynamic, with strength and vigor, like a Winston Churchill would have? Or do we do it in a more warm and fuzzy way? Given Bush's past communications on the subject, I would've guessed that he would've been more Churchillian and less Bill Clinton.

What was stunning to me about what he did Tuesday night was, when he was talking about the things Iraq had done, the torturing children in front of their parents and raping and pillaging and all of the terrible things that he was talking about, and then going on to make the case for going in to Iraq, he wasn't strident. He wasn't Churchillian. He was very, very touchy-feely, sober, somber and restrained. And I think that was exactly the right tone that he needed to hit, and was really quite surprised that he had it in him. In fact, there was a point, toward the end of his argument on Iraq, where his eyes got teary. And that, if it's genuine, teary eyes always work. Bill Clinton, when he was genuine with his teary eyes, was enormously compelling. When it looked like it was forced and acting, obviously, he gave critics an opportunity to respond to that. This was the first time I'd ever seen Bush be so heartfelt and so soft and touchy-feely and I think it came at a perfect time for him.

You've said that one key to a successful speech is to have a lasered message -- that is, simple terms, a sound bite. Was there a line in Bush's State of the Union speech that we'll remember?

There were two or three times where he said stuff and I thought, "Oh my God! His speech writer is having a good moment." The one I remember is where he was listing all the horrible evils -- torturing children in front of their parents and stuff like that. What did he say -- "If this is not evil, then evil has no meaning." That was good. That was really good. We talked earlier about how he changed "axis of hatred" to "axis of evil." And he kind of had to define that, and to put a human context on it. And that was a brilliant way to do that. Because any parent could imagine -- having your child tortured in front of you, what could be worse? And evoking those emotions and then saying, "That's what I meant, that's who this guy is."

But again I think the message of the speech, the thing he did accomplish, there was a warmer, Bill Clinton-esque quality that came out at the end of the speech that was as connecting as I've ever seen George Bush be. And I think it helped his case. But I still think he's not made the case.

Until he can come up with a really compelling, logical rationale for not only going in, but for all of the different possibilities that might happen, there are many people who are going to feel this is another situation like Vietnam. Until he does that, I think that no matter how emotional he is, he's not going to carry the day with a lot of people in the United States and around the world.

Shares