Methyl bromide gas is some pretty nasty stuff.

The toxic pesticide has a habit of affecting non-target organisms as well as the pests it seeks. Human exposure to too much of it can lead to death, respiratory failure, central nervous failure and permanent disabilities; pregnant women exposed to it risk fetal defects. And, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, "methyl bromide contributes significantly to the destruction of earth's stratospheric ozone layer" and for that reason, on Nov. 28, 2000, the U.S. government agreed to a 70 percent reduction of its use this year, with a complete ban to kick in by 2005.

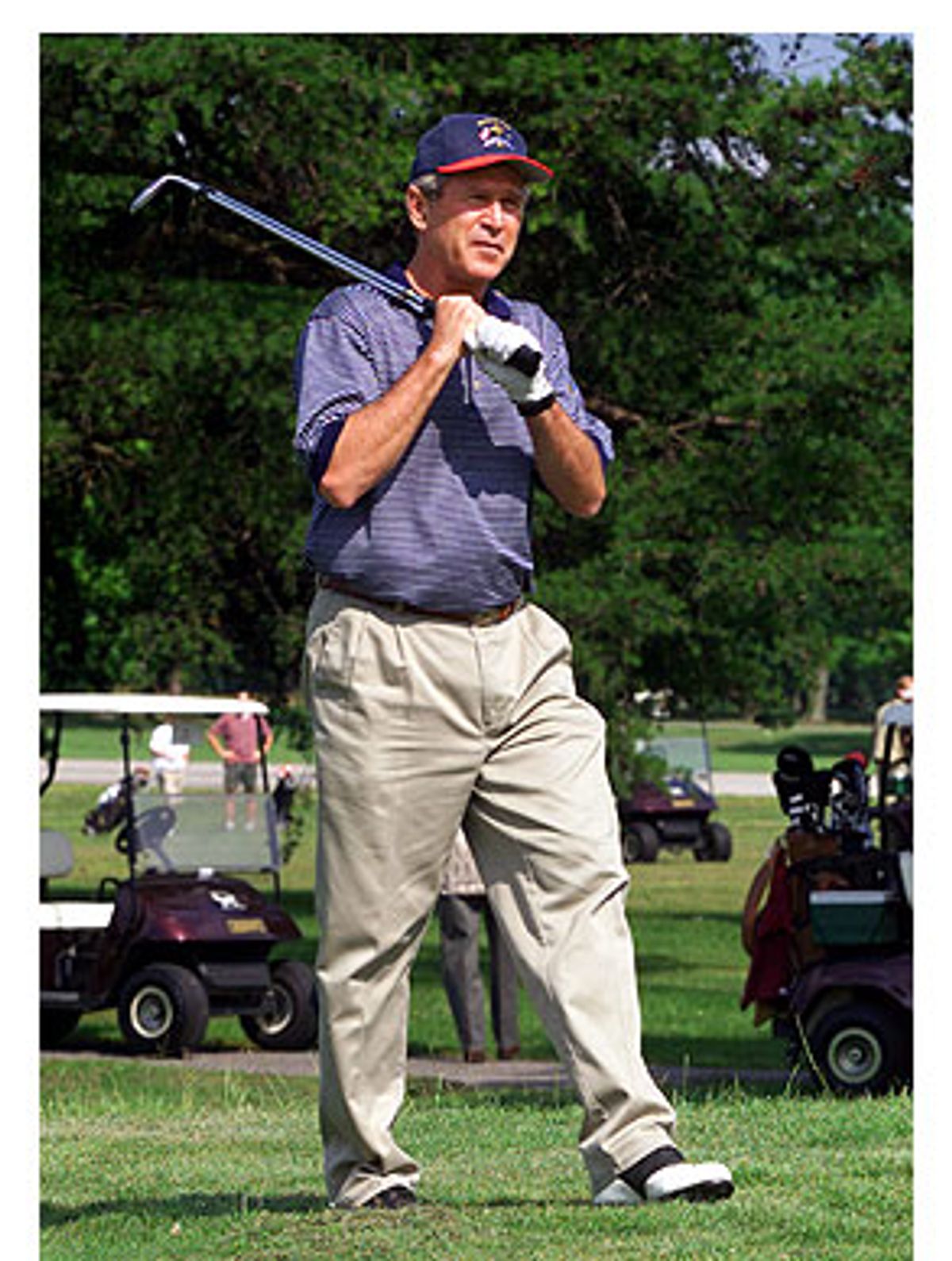

The Bush administration, however, is considering applications for 56 exemptions from this ban and, according to press reports, is planning to grant many of these industries their wish. Ranging from the Tobacco Growers Association of North Carolina to the California Tomato Commission, the 56 groups seeking "critical-use exemptions" are doing so because they feel compliance with the ban is not technically or economically feasible. No suitable alternative to methyl bromide exists, they claim, and any replacement would pose an undue economic hardship on their industry.

One might be inclined to feel some sympathy for the Virginia Tomato Growers, the Sweet Potato Council of California or the Rice Millers' Association. They feed us. But golfers? Specifically, in its application (click here for a PDF copy; requires Adobe Acrobat) the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America wants EPA Administrator Christie Todd Whitman to allow its members to use, from 2005-2007, 734,400 pounds of a chemical so toxic and environmentally damaging it will be banned nearly everywhere else. This exemption is sought so the courses can continue to look pretty.

"Methyl bromide is used on golf courses when they resurface greens," explains GCSAA spokesman Jeff Bollig. "Greens are covered with a tarp sort-of material and they shoot the gas in -- it kills the existing grass so it can be replaced with a better strain."

And the EPA, according to some reports, appears inclined to grant the golf association its wish. Naturally, the environmental community is up in arms. "We don't think that methyl bromide should have a place on the farm, let alone the fairway," says Allen Mattison, spokesman for the national Sierra Club. "There is certainly a better solution than a substance that depletes the ozone layer and causes irreversible environmental harm."

The Bush administration, however, has been able to slowly roll back a series of such restriction in the past few years, with little notice, or outrage, from the public at large. For example, the administration has suspended or revoked rules against raw sewage discharges, dumping industrial waste in rivers and streams, and the use of snowmobiles and personal watercraft in national parks. It has suspended regulations giving watershed health and wildlife higher priority than timber sales as well as ones that required mining companies to clean up mine-related pollution. Bush is also considering new rules restricting the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act.

Now, the right of golf courses across the country to remain plush and dandelion-free might get in the way of a little easy breathing. Environmentalists are crying foul. But the administration -- and golf developers across the country -- appear content to cry: Fore!

The methyl bromide brouhaha highlights an issue that environmentalists have been complaining about for years. Golf as it is played in America today, they argue, is an environmental scourge. "Golf is the sleeping giant threatening the environment," declares Mark Massara, director of the Sierra Club's California Coastal Campaign.

That the GCSAA should find itself a potent political force along with big tobacco and big agriculture should surprise no one. Golf is huge. In the last decade, the U.S. has seen an explosion in golf course construction -- from 150 new golf courses per year a decade ago to a peak of 524 new courses in 2000, according to the National Golf Foundation. As of last June, there are 17,816 golf courses in the U.S. -- more than 20 percent of which have been built in the last decade or so.

NGF research also concludes that the nation's 26 million golfers -- more than 12 percent of the population -- spent $23.5 billion in 2001 on equipment and fees.

These numbers mean clout. The growing golf industry has yet to be fully studied in the same way that, say, health insurance companies are. But -- bearing in mind that many of golf's environmental issues are local land-use ones made at the county and township level -- an analysis of donations to federal candidates by the Center for Responsive Politics indicates that golf and golf-affiliated corporations gave upwards of $220,000 in the 2001-2002 election cycle, more than two-thirds of which went to Republicans. That rates the golf industry somewhere between gun-control groups and antiabortion ones as a "special interest."

Upon hearing of the pending ban, many of the GCSAA's 22,000 members instructed the organization's government affairs department to reach out to the EPA for an exemption. "We know these people," Bollig asserts. "The current administration may be a little bit more receptive to us. Christie Todd Whitman is a fan of golf." The EPA did not return a call for comment. It might seem counterintuitive, at first. After all, these are gorgeous green rolling hills -- expansive fields parenthesized by wooded nooks, studded with ponds and lakes -- some of the most gorgeous spaces known to man. Ah, so one would think. But the truth is that many if not most golf courses are -- as one environmental official once quipped - "about as environmentally friendly as Las Vegas."

Vegas, however, was built atop 84,272 square miles of desert. With golf courses averaging a size of 150 acres apiece, that means about 2.5 million acres -- half the size of Connecticut -- is being devoted to a sport that largely caters to the elite. It'll cost you $350 to play 18 holes at Pebble Beach, for instance, $375 with a cart. (Lotta the guys there seem to need the cart, by the way.)

And often these oases for the plaid-panted set are carved from nature the way one might attack a coffeecake -- the result of a ravenous clear-cutting of forests and fields. The 18 million gallons of water it takes on average to keep each one lush for a year can be problematic in times of drought. Endangered species are threatened. And that's the stuff we know about.

Golf courses are often also as unnaturally pumped-up as a steroid-addled East German shot-putter. A 1982 EPA survey reported that the average golf course used about three times the amount of pesticides than even the most pesticide-friendly agribusiness. Those nasty chemicals have a way of making their way into water supplies because the topography isn't real -- the hills and dunes are often constructed out of thin air, sometimes paved over with gravel and then topped with topsoil -- prettier than a parking lot, but not so different in the end.

In the past, chemicals haven't needed to leach into the water supply to become deadly.

In August 1982, after a few rounds of golf at the Army Navy Country Club outside Washington, D.C., Navy Lt. George Prior, an athletic, healthy, 30-year-old Navy flight officer, developed an odd rash on his back and began suffering flu-like symptoms. He checked himself into Bethesda Naval Hospital, where his body soon began to burn from the inside out. His internal organs started failing, blisters bubbled on his skin. After slipping into a coma, he died within days. A Navy forensic pathologist concluded that Prior had died as a result of a severe allergic reaction to Daconil 2787, a fungicide that had been sprayed on the course. Prior's widow sued Diamond Shamrock, the fungicide's former manufacturer; the case was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. She soon gave the National Coalition Against the Misuse of Pesticides (NCAMP) a rather sizable donation.

While awareness of the potential harms of pesticides has increased dramatically in the last 20 years, Jay Feldman, executive director of the NCAMP, says that their use remains a huge problem on golf courses, which he says are second only to orchard crops in terms of the amount of pesticides they absorb. Feldman remains convinced that even though there are no other known incidents like Prior's, it isn't because they haven't happened, but because Prior -- as a military man on a military course -- was afforded an extra-diligent autopsy. "We're missing a lot of elevated rates of illness and diseases that are associated with pesticide exposure on golf courses," Feldman insists. Studies would show "that other peoples' lives have been cut short as result of exposure to pesticides on golf courses."

That's the challenge for golf's critics -- the lack of concrete data, of concrete facts and figures. Anecdotes abound, of course -- like the four LPGA players diagnosed with breast cancer in 1989. ("We're beginning to wonder," LPGA president Judy Dickinson told USA Today in 1991, "because we've played among these chemicals all these years.") Or the Twilight Zone-esque experience of golf great Billy Casper, who has 51 PGA Tour titles and nine Senior PGA wins. Casper once told Golf Magazine that pesticides at Florida links used to cause him significant health problems, once even causing him to drop out of a Miami-area tournament after 36 holes.

"The course had been heavily sprayed and there was weed killer in a lake," Casper said. "When I got to the course for the third round I couldn't hit a wedge shot 30 yards -- I didn't have the strength. My eyes were bloodshot, my complexion was very ruddy and my right hand was swollen from taking balls from the caddie. My doctor diagnosed acute pesticide poisoning."

And in 1994, researchers at the Department of Preventative Medicine and Health at the University of Iowa presented to the GCSAA the results of a study of 686 of its members who died since 1970. The news was not good. Golf course superintendents contracted non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, brain cancer and prostate cancer at more than twice the national average, and large-intestinal cancer at almost that. While noting that other occupations continually exposed to pesticides -- like farmers -- had similar medical problems, the report didn't take into account matters such as heredity and smoking and thus could not necessarily "establish any cause-and-effect relationship from the data."

However, exposure to too much "2,4-D," the most widely used herbicide in the world, can cause nervous system, kidney and liver damage, according to the EPA. Studies published in the Journal of the American Medical Association and Epidemiology magazines indicated a correspondence between spraying 2,4-D and an increased occurrence of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma among Kansas and Nebraska farm populations regularly exposed to the chemical, a correspondence that 2,4-D's manufacturers, citing their own studies, deny wholeheartedly.

Pesticides are poisons -- ones that can never be legally labeled "safe" in this country, because they never can be guaranteed as such. Some pesticides on the market are carcinogenic, or cancer-causing, while others have been linked to reproductive problems, nervous system disorders and birth defects. Their limited use is permitted when their proposed benefits -- like, say, protecting crops from fungi or insects so as provide food for society -- theoretically outweigh their potential harms. But when the pesticides are used just to keep a golf course emerald green, their application becomes questionable.

Ironically, a greenskeeper's itchy trigger finger on the pesticide gun once led to the golf industry leading the way in environmental regulations -- albeit involuntarily. In 1988, after a rash of dead-bird incidents on golf courses -- including more than 700 dead Atlantic Brant geese on a course in Long Island -- the pesticide diazinon was banned from use on U.S. links altogether, though that of course didn't come without industry protest. "The ban on diazinon was unnecessary and an overreaction to a few incidents," whined the manufacturer, Ciba-Geigy.

It wasn't until late 2000 that the EPA banned its use everywhere in the U.S. altogether.

Golf superintendents (or "head greenskeepers," for Caddyshack fans) argue that they're much more careful now. The Pebble Beach Company has been particularly vigilant in working to combat the pitch canker disease that threatens the Monterey Pine, raising funds from a golf tournament to aid the cause. "Honestly speaking, in many years past there probably were times on this golf course where the maintenance wasn't in compliance with the environment," acknowledges Pebble Beach Golf Links superintendent Tom Huesgen. But, he argues, golf course executives have been educated significantly in the past decade.

Still, Pebble Beach Company officials refuse to tell me the amounts of pesticides they use. "We don't have a volumetric amount," Huesgen insists, though he has the exact numbers at his fingertips for less controversial fertilizers. (He is much more forthcoming when asked if Pebble Beach uses methyl bromide. "No," he says. "Definitely not. Absolutely not.")

That reluctance to fully disclose is common industry-wide. In the early 1990s, New York state's liberal activist attorney general, Robert Abrams, tried to find out more about the use of pesticides on golf courses on Long Island, but only 52 out of 107 courses responded to his office's inquiry. The resulting report, "Toxic Fairways" was nonetheless devastating, concluding that groundskeepers were using too many pesticides too often and should altogether cease using the pesticides containing known or probable carcinogens.

Neal Lewis, executive director of a Long Island environmental group called Neighborhood Network, took Abrams' numbers and multiplied them out, concluding that across the nation golf courses use 65 million pounds of dry bulk pesticides and 2.9 million pounds of liquid pesticides a year, a staggering amount. Lewis wants golf courses to embrace "organic golf" without pesticides. "The original game of golf goes back several hundred years, and certainly it did not rely on the use of toxic chemicals back then," he says.

His opponents, like agronomist Matt Nelson of the USGA, counter that reliable alternatives to pesticides are as of now a pipe dream. Golf is a multibillion-dollar big business, Nelson recently wrote in Golf Course News. "Golfers aren't likely to flock to golf courses with extended periods of widespread dead grass and playing conditions reminiscent of the early 1900s." Right now, there's no sign that will happen. As Lewis points out, new state laws in New York requiring pesticide users -- even just common home owners -- to give their neighbors 48 hours notice before application, and to put up a warning marker 24 hours before spraying, exempt one key industry: golf courses.

Golf courses enjoy support for a very simple reason: The power of the people who love them. In idyllic, seaside Monterey, Calif., the rich white men running the Pebble Beach Company want to tear down at least 9,000 trees in nearby Del Monte Forest to build some new links that will be called -- what else? -- the Forest Course. And as if that weren't enough, the man leading the charge is none other than that squinty ex-mayor of nearby Carmel, actor Clint Eastwood, the leading member of the Pebble Beach Company's board of directors.

But while environmentalists and neighborhood groups face off against Eastwood and his low-handicap drifters, it's clear that what's going on here at Pebble Beach is representative of golf -- and its repercussions -- in general.

Pebble Beach executives are seeking final government approval to clear-cut at least 9,000 Monterey pines, which were once declared endangered by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

They do this not because there aren't enough courses in the area -- there are 23 places to practice your swing on the Monterey Peninsula, five of which the Pebble Beach Company owns -- they do this for the money. This, of course, is not how they presented the matter to local voters in November 2000 -- they sold it as a boon to nature. Golf course developers can thus be as deceptive as their unnaturally green projects.

On a trip to Pebble Beach, I tool around with superintendent Huesgen on his golf cart. The Pebble Beach Golf Links is, indeed, a gorgeous course -- particularly the much-photographed, fabled 7th hole which juts out on the tip of the jetty, with the surrounding crash of breaking waves in Stillwater Cove.

Huesgen says that the company is committed to the environment. As for the 9,000 Monterey pines his bosses want to chop down, "there's a lot more to it than taking down trees," he says. "You're right in saying that some trees will be removed, but that's only a small part of the story."

But there is reason to doubt the authenticity of the Pebble Beach Company's version of any "story." In November 2000, Monterey County voters had the chance to vote on Measure A, a ballot initiative pushed by Pebble Beach Co., that amended, for the second time, their 1992 request to build the Forest Course. Since the company was asking for permission to build fewer homes, and chop down fewer trees, than its previous two requests, the company figured it could sell Measure A as a pro-environment move. Voters were besieged with glossy fliers. One sent by a company-funded group called the "Committee to Preserve Del Monte Forest" featured lovely nature shots and language urging locals to "vote for the environment ... preserve the Del Monte Forest."

One word that never appears in the flier? "Golf."

Nothing about the minimum 9,000 Monterey pines that will be chopped, or the mountain lions, black bear, great horned owls, coyotes, deer or gray foxes that will be turned out of their homes. Even many pro-golf types roll their eyes when discussing the insatiability of Pebble Beach Company execs. When it comes to its lust for more courses, so as to accommodate more players and more fees, there's only one green guiding the executives' path.

The Pebble Beach Company sank an estimated $1 million into its campaign for Measure A. The environmentalists launched a $30,000 counter-effort, but their opponents' campaign included a very public role for Eastwood -- who in 1999 bought the company for $820 million with three other major (and myriad other minor) investors: 61-time U.S. PGA Tour winner Arnold Palmer, former baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth, and ex-American Airlines honcho Richard Ferris. Omnipresent TV ads featured the 72-year-old actor/director and his 37-year-old wife, Diana Ruiz, a popular former anchor at the Salinas NBC station, standing in the middle of a pine forest selling Measure A as a green move. The measure passed overwhelmingly, by a 2-to-1 ratio.

"Everybody in town thought they were voting to save the Monterey pine," Massara says. Dirty Harry, indeed. Massara calls the campaign "a fascinating exercise in celebrity worship in group dynamics."

But disingenuousness is par for the course (sorry). Golf course owners all over the country trot out the claim that their links have been certified by "Audubon International," for example -- but they do so assuredly knowing that few people know the difference between Audubon International (funded by the U.S. Golf Association as well as developers like Arnold Palmer Golf Management, Marriott Golf, PGA Tour Golf Course Properties, and the Walt Disney Company) and the National Audubon Society, which unsuccessfully sued Audubon International in 1991 for using its name.

And flying in a helicopter above the Monterey Peninsula, seeing how much the landscape is besotted with golf courses -- Eastwood even just built another one on top of a mountain -- it does seem that their Ryder's Cup runneth over. Massara argues that "a large percentage of our country is already dedicated to this sport, which a very narrow group of people can afford to pursue."

And there are environmentalists who pragmatically accept that golfers aren't going anywhere. Peter Stangel, regional director of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, runs his organization's Wildlife Links Program, which is funded by the USGA. "It's an accepted fact that a lot of courses are out there and they're being built all the time," Stangel says, passing no judgment. Once a community makes a decision to allow a course to be built, "we provide them with the tools to minimize its impact and to protect biodiversity."

Stangel is optimistic. "There's been tremendous progress within the golf industry with regard to water conservation, recycling and reducing pesticide and fertilizer use," he says, noting that many courses have realized, if nothing else, that reducing the use of chemicals will save them money. Paul Parker, director of the independent Center for Resource Management, agrees, pointing out that 85 percent of U.S. golf courses have at least one official pesticide applicator, certified by the state, so their use is far more responsible.

"There are certainly bad eggs out there and clearly not every golf course is as conscientious as they should be," says Stangel. Though his group at the NFWF and Audubon International are constantly sneered at by fellow activists as some sort of environmental Uncle Toms, he argues that they serve an important function by being alongside club owners and not just on picket lines.

One somewhat odd proposal comes from the EPA's John Harris, the national program coordinator for Superfund redevelopment, who proposes building links on formerly contaminated Superfund sites instead of destroying previously unmarred nature. While it sounds counterintuitive, to say the least, that the solution to the environmental problems of golf courses is to build the courses on even sketchier plains, Harris says that since the lands aren't natural, no one will care if the course is "capped" with gravel and concrete and various ways to ensure that nothing seeps up or down.

"We think if you do it right these golfing uses of our sites may actually be more environmentally friendly than the old-style golf courses with their high pesticide use," Harris says, a frightening thought that pretty much says it all.

Shares