One of George W. Bush’s biggest campaign blunders was his February 2000 visit to South Carolina’s Bob Jones University, a bastion of the segregationist South that had finally admitted some students of color, but still banned interracial dating. Critics had a clear shot at Bush, whose own brother Jeb could have fallen victim to the university’s invidious rule, since his wife Colomba is Mexican (producing three mixed-race grandchildren whom the first President Bush famously called “the little brown ones.”) “You could make the case that ‘compassionate conservatism’ died Feb. 2 when Bush appeared at Bob Jones U,” conservative William Kristol fulminated. Of course, the beleaguered GOP candidate had to denounce the school’s interracial-dating ban, and soon even benighted Bob Jones U. did away with it, too.

Nowadays, with the president’s brother a miscegenationist, and the right’s favorite black man, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, married to a white woman, it’s hard to find anybody who will publicly attack interracial romance, beyond the fringes of white supremacist Web sites — and, of course, the popular black media. Take November’s Essence magazine, a glossy geared to black women, which featured a major spread headlined “Bring me home a black girl” by contributing editor Audrey Edwards, laying out how and why she’s indoctrinated her stepson not to date white women.

Edwards, a respected, veteran journalist, is unapologetic about her racially biased home training. “For Black women, one of the inequities on the current playing field has been the rate at which Black men are marrying outside their race,” she says. Too many black men think they’re marrying up socially by marrying out racially, Edwards believes, so it’s up to black moms to convince their sons by any means necessary — including guilt, shame and ostracism — not to date white.

I tried not to take Edwards’ piece personally, but it was hard, because I’m one of the race mixers; I have intermingled, interdated, intermarried. My ex-husband, still a close friend, is Jewish, my boyfriend is black, as are several of my best female friends. I know from experience: Get too close to the fiery eruptions of toxic, black double standards on race, and you will get burned. The first time I encountered the old “I like whites just fine — but I wouldn’t want my brother to marry one” hypocrisy, it felt like I’d been slapped. Over the years I’ve come to see that as a minority sentiment in the black community, and despite stories about angry sisters harassing white woman-black man couples, by far the worst treatment I’ve encountered as a result of being with a black man — dirty looks, nasty comments, rudeness — has been from whites.

Still, it’s stating the obvious to observe that no mainstream magazine today would publish a comparable piece by a Caucasian mom exhorting her son to “Bring me home a white girl!” (However, Jews are allowed to voice such misgivings publicly; convicted Iran-Contra felon Elliott Abrams developed a sideline as a crusader against Jewish intermarriage before Bush hired him as the National Security Council’s director of Middle Eastern policy. Even after the Bob Jones debacle, nobody from the administration asked Abrams to renounce his stand against Jews marrying non-Jews, but I’ll get to that later.) Yet black-oriented magazines and Web sites continue to clamor with a debate over interracial romance that’s alternately infuriating and poignant — and also on a collision course with demography.

In a recent Gallup/USA Today poll, 57 percent of teenagers said they’d dated someone from another race, up from 17 percent just 20 years ago. The number of interracial marriages has more than doubled in that same period, and while blacks are still less likely to marry outside their race than other minority groups, the number of black-white marriages has almost tripled. Maybe most remarkable, because Edwards is right that the trend has favored black men, the number of black women marrying white men has more than quadrupled, while the number of black men with white wives only doubled. In 1998, black-white couples in which the wife is black made up 37 percent of all black-white marriages nationwide, up from only 22 percent in 1980. It’s not 50-50 parity yet, but at that rate of change, we’ll get there soon. Race-mixing is clearly the future, and the more I looked at the data, the more I felt sympathy for Edwards, rather than resentment, because she’s clearly clinging to a bygone past.

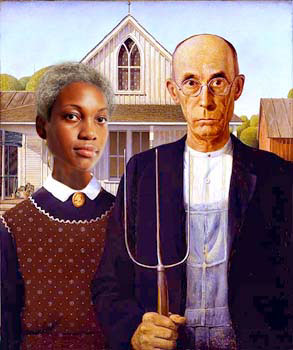

But when it comes to race, the past is never very far away. Beneath a discussion marked by surface consensus — Of course we can all get along! I mean, Justin Timberlake dated Janet Jackson after Britney! — roils confusion and rancor. Now along comes Randall Kennedy and his new book “Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity and Adoption,” whose tone, against all odds, is scholarly, sober, even soothing. Kennedy’s great accomplishment is his exhaustive recounting of the history of interracial intimacy in America — from slavery and Jim Crow through the civil rights movement, up to Spike Lee’s “Jungle Fever,” interracial adoption battles and even online dating today. He clears up some misconceptions about famous folks who did or didn’t have interracial dalliances — Booker T. Washington probably didn’t, despite some claims to the contrary, but Strom Thurmond did. Yes, the man whose segregationist run for the White House in 1948 cost Trent Lott his Senate leadership 55 years later almost certainly fathered a child with his family’s black maid, Kennedy concludes — a fact that was revealed in Marilyn Thompson and Jack Bass’ biography, “Ol’ Strom,” but was barely mentioned during the national conversation on race that ensued after Lott’s racist remarks at Thurmond’s centennial.

Having looked at all sides of this historical morality play, the black Harvard Law School professor takes a strong and bracing pro-mixing stance: “The flowering of multiracial intimacy is a profoundly moving and encouraging development … It signals that formal and informal racial boundaries are fading.” One can share Kennedy’s racial openness and optimism and still be skeptical, though: Does interracial intimacy herald the end of racism?

We don’t know — yet — but Kennedy’s book gets us closer to an answer. He offers tantalizing hints of the way psychosexual issues and economic ones combined to create the taboo against miscegenation, and he tackles related questions that emerge from our new interracial alliances. Are black men (and now, maybe, black women) ever trying to marry up when they marry out — and is that ever OK? Is interracial intimacy an engine of racial progress, an indicator of it, both, or neither? And is there ever a case for racial solidarity, for discouraging cross-racial intimacy, whether in dating, marriage or adoption?

Kennedy knows exactly how complicated those questions are, and he grapples with all of them — always sympathetically, occasionally a little naively. I scoured the Web to find out if he’s married to a white woman, and was relieved to learn his wife is black — then ashamed of my relief — but not particularly surprised. He sometimes seems a visitor in the land of interracial romance, but mostly that makes for interesting observations. Sadly, given how polarizing this debate can be, it actually matters that Kennedy isn’t justifying his own choice of a white wife, that he doesn’t particularly have a stake in this battle. That is, beyond the stake all of us have: to create a prosperous multiracial democracy unblemished by the tragic inequities between blacks and whites — in family income, in education, in health, in crime statistics, on virtually every major indicator of well-being we use — that persist to this day, even as we intermarry and congratulate ourselves for it.

Reading “Interracial Intimacies” alongside Essence’s “Bring me home a black girl,” it’s hard not to notice the way racist whites and some supposedly enlightened civil rights advocates have traded places. “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents,” wrote the judge who upheld Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage in the wonderfully named Loving vs. Commonwealth case (which ultimately resulted in the Supreme Court overturning all such statutes, but not until 1967). “The fact that he separated the races shows he did not intend for the races to mix.” Early chapters of Kennedy’s book show a long history of bizarre attempts to enforce laws against interracial dating, marriage and adoption, with police, prosecutors, lawyers and judges going to unbelievable lengths to “prove” an individual’s race — stories that would almost be funny if they weren’t so cruel and tragic.

The book opens with the awful tale of Jacqueline Henley, a motherless New Orleans toddler whose white relatives surrendered her to the state in 1952, when it became clear, as the child got older and darker-skinned, that her father was black. Henley’s story promised to have a happy ending when the black foster family she was placed with decided to adopt her — until they found they couldn’t, because she was listed as white on her birth certificate, and Louisiana law prohibited interracial adoption. Lawyers tried to free the girl from her no-man’s land of racial categorization, but failed. The adoption was prohibited. Eventually, though, Henley was adopted by a black Chicago family, when Louisiana officials let her cross state lines to find a home, having made it impossible within its borders.

Anyone familiar with contemporary racial politics knows exactly where Kennedy is going with the Henley story. In 2003, it’s painfully clear that outside the Web sites of racist white nutjobs, the only folks obsessing about racial categories, inveighing against racial mixing, advocating race-matching in adoption and preaching racial solidarity tend to be civil rights advocates, mostly but not exclusively black. The NAACP, backed by the Asian Pacific Legal Consortium, opposed the Census Bureau’s decision to let Americans check multiple boxes in the 2000 count, afraid the creation of a new multiracial category of Americans would dilute black political power (since, thanks to the history of often involuntary mixing that Kennedy illuminates, the vast majority of blacks have non-black ancestors). The NAACP urged the Census Bureau to designate as black anyone who checked multiple boxes, if one of the boxes was “black” — a novel update on the pernicious one-drop rule that racists once used to designate anyone with African ancestry black. And while it’s black conservative Ward Connerly who is behind the move to abolish the collection of racial data by California agencies, the entire black civil rights establishment is arrayed against him.

Harking back to the plight of Jacqueline Henley, Kennedy points out that today, groups like the National Association of Black Social Workers have worked hard to prevent white parents from adopting black children, calling it a form of “genocide” — meanwhile leaving black children to languish in foster care, just like Henley did 50 years ago, even when willing white parents are available. Although some critics have complained that the book pays insufficient attention to interracial intimacy beyond the borders of black and white — which Kennedy admits — his most scathing chapter is about the Indian Child Welfare Act, which he argues is a pernicious gesture of racial engineering that makes babies of Indian ancestry essentially the property of their tribes, not their parents, with eerie echoes of the plantation system.

I was tempted to argue that Kennedy makes too much of black efforts to enforce racial matching. While such arguments developed enormous sway in the 1970s, the ’80s and ’90s saw an ideological and political backlash, and by 1996 the Interracial Adoption Act expressly forbade racial matching policies. Still, many states, most notably California, have statutes that permit public workers to consider a prospective parent’s “cultural competency” — a creepy term that’s shorthand for whether a parent knows enough about an adoptee’s race, culture and ethnicity to raise a healthy, happy child.

You might ask what’s wrong with such efforts, until you think about what it means: Who is going to judge what constitutes “competency” to raise a black child? Ward Connerly or Louis Farrakhan? Audrey Edwards or Janet Jackson? Kennedy cites a Rhode Island case in which a white couple’s ignorance about Kwanzaa — a faux-African holiday invented by black nationalist bully and FBI informant Ron Karenga, and ignored by many blacks — was used against their adoption of a black child. Today, a whole diversity industry trades in what some people might call stereotypes of racial behavior, in the name of cultural competency — and Kennedy argues that when it comes to adoption, anyway, it’s black children who suffer from it.

But if certain racial stereotypes, however well intended, hold too much power when it comes to adoption policy, Kennedy shows that such biases are even more widespread when it comes to interracial dating and marriage. Yet he only touches on another fascinating way in which white racists and black opponents of mixed marriage have traded positions: Now it’s blacks who promote the most noxious stereotypes of men and women who mix, in order to stigmatize interracial romance — and even more intriguing, in these black stereotypes of mixed couples, whites and blacks have switched roles, too.

In the white racist imagination through Jim Crow, of course, blacks were hypersexual and seductive, desired by only the most depraved white men and women, who wanted them for their renowned sexual prowess and nothing more. But today, according to the nouveau black stereotype, white women are the freaks, sexually wild as well as easy, while virtuous black women demand commitment before giving it up — and even then they stick to an erotic menu that can only be termed vanilla. (The best pop-culture crash-course on these issues is the hilarious 2000 film “The Brothers,” in which bachelor Bill Bellamy swore off black women because they’re too “demanding” — and then got his ass kicked by a feisty white girl — while the married D.H. Hughley spent the movie trying to coax oral sex out of his black wife, who was raised to think it’s “nasty.”)

Meanwhile, the other half of the stereotype holds that white men who date black women are only into sex, while black men who date white women are chasing not sex but status. (You know, prosperity, not that other P-word.) In a July 1999 Essence piece — yes, it’s Essence again — on black women who date white men, one source recounts that she wouldn’t allow her white date a goodnight kiss because she was afraid his interest was “just about wanting to know what a Black woman looks like naked. Is it just that you want to see my nipples, to see what dark nipples look like?” she wonders. Others worry about the “Makumba-love, bangi-ass fantasy.” Conversely, the myth goes, black men today aren’t out to rob a white woman of her virtue; they just want her Rolodex, and her daddy’s, too. In her Essence essay, Audrey Edwards lamented the perceived tendency of successful black men to marry white, and Kennedy notes that such worries are behind most black disapproval of relationships between white women and black men.

The nastiest version of the myth, however, holds that while those black men believe they’re marrying up, they’re actually marrying down, almost always choosing white women who are lower class, less well educated — and unattractive to boot. On that issue the best pop-culture primer remains Spike Lee’s iconic “Jungle Fever.” Although in interviews Lee has complained about the plague of black men dating “ugly” white women, not just lower-class ones, he cast the gorgeous Annabelle Sciorra as Wesley Snipes’ white girlfriend. That’s because ugly might make for a useful, stigmatizing racial myth, but it’s bad box office, and Spike ain’t about socialist realism, anyway. Still, Sciorra’s sexy Angie was a working class Italian with a high school education, while Snipes’ Flipper Purify — Purify — get it? — and his lovely black wife had graduate degrees. Of course nature intended for Flipper and his wife to wind up back together — class tells — and so they do.

Maybe the most radical thing Kennedy does, albeit briefly, is suggest the possibility that the conventional anti-mixing wisdom about successful black men — they get some money, then they marry white — sometimes works the other way: Some black men (and black women) may choose white partners, then become successful. And not because they face less racism (in fact they may face more, given lingering prejudice from blacks and whites), but because of the social capital and wider world of connections they acquire with that merger — and maybe even because of psychological traits that leave them open to finding a white partner.

The paucity of research on these questions is amazing. I saw one intriguing study of 1990 census data showing that in upper-income American marriages (over $100,000), as well as marriages in which both partners have postdoctoral educations, there are almost as many black-white couples as there are couples in which both partners are black — even though black-white marriages make up only 12 percent of black marriages overall. No one has really looked at what this means. It might simply mean that affluent whites are raising the income level of their black spouses; it might mean successful black men — and now women — wind up marrying whites; it might mean racism and other bars to success faced by blacks are reduced if they take a white spouse. But it might also mean that men and women inclined to marry outside their race have other traits — curiosity? courage? self-confidence? — that make them materially successful.

We really don’t know. But Kennedy approvingly quotes Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson’s bold pro-integrationist theory that intermixing is a good thing, especially for blacks, because it widens their networks and increases their social capital, as well as that of their offspring. You can see why that’s offensive to some African-Americans, who ask: Can’t we increase the cultural, social and economic capital of black families? Can’t we lower the barriers of racism, so black people who fall in love with other black people have the same advantages as those who love whites?

But social progress may not work that way. Those who are willing to venture out into new worlds and explore frontiers are often rewarded for their courage. And marriage has always been an economic arrangement, in which partners choose one another, and give one another advantages, in ways that have nothing to do with love, even if they only cop to the fairy tale version of coupling.

I think Kennedy overstates the roles that sexual fear and projection, and the threat of racial “mongrelization,” have played as the motivation behind racially discriminatory laws. Maintaining economic privilege for whites has always been more important. From slavery to the New York City draft riots to Reconstruction, up through the opposition to welfare, busing and affirmative action that emerged in the 1960s and persists today, the desire to maintain white advantage — or in the working class, the desire not to face more disadvantage, thanks to competition from another pool of exploitable workers — has been the force driving most racist laws, and the racial prejudice that survived those laws’ repeal. That’s why it makes sense that today, the most (publicly) acceptable black critique of intermarriage centers on the fear that the trend will hurt the black community economically, that it’s causing an exodus of good black husbands who, choosing white wives, flee to the promised land of integration — which means whiteness.

When those arguments fail, of course, opponents resort to sexual stereotyping and stigmatizing, name-calling and contempt. But it didn’t work for white opponents of intermarriage, and it won’t work for their black counterparts. It’s wrong, it’s racist — and the drive to mix is just too strong. My advice to women like Edwards who are trying to revive the taboo against interracial dating is simple: Remember Sexuality 101, in which taboo heightens attraction. And I’d also suggest a lesson plan for Sociology 2003: Defining a community by the threats to it is not an appealing vision of community.

As an outsider who’s been intimate in the world of blacks and Jews, I can certainly testify from experience that neither approach is working. Of course, Judaism is a religion, not a race (at least the way most people understand the concept), and so it’s been possible for some people who worry about Jews intermarrying themselves out of existence to come up with a compromise approach, involving outreach to non-Jewish spouses based on the appeal of Judaism — its spiritual and cultural traditions of wisdom, justice and comfort in the face of suffering and loss — rather than just guilt about high rates of Jewish intermarriage. But there’s really no comparable black compromise with intermarriage, at least for those with views like Edwards’. An old friend and mentor of mine who worked on black poverty issues used to tell me, “Black is a state of mind,” and he welcomed white co-workers, as well as the white girlfriends or husbands of black friends who shared his values, into his vision of community. That’s not possible for racial essentialists, who define community by color.

By the end of Kennedy’s book, though, unexpectedly I felt a flash of sympathy for Edwards. Because if you insist that no one should ostracize blacks and whites who love one another, you have to have some human sympathy for black women who love black men, and are genuinely pained at the shortage of them. Stanley Crouch’s wildly pro-miscegenation novel “Don’t the moon look lonesome” actually captured it well, when the tough, screwed-up Cecilia explains why she can’t get over wanting a black man — a man who is the color of the men in her family, the color of childhood, the color of tenderness and love. “All I want in the world is one of those kinds of men I saw what I was just a little kid,” Cecilia says. If the heart has its reasons, hers does too. None of us can be blamed for whom we love.

That said, we can’t preach racial separatism for one group, and not for everybody. Although the current clamor to revive taboos against interracial dating lacks the force of law — one thing white supremacists used to have on their side that black mothers like Edwards clearly don’t — it’s still the wrong message for a multiracial democracy. And clearly most people understand that. There’s no doubt all this is easier for the younger generation. Edwards is in her 50s, Kennedy and I are in our 40s; Essence’s target audience seems to reach from our age down into the 30s. In the pages of Africana.com, and other sites that seem more geared toward younger black people, there’s a little less angst and a lot more acceptance, by women as well as men.

Still, interracial love can’t by itself eradicate racism, and Kennedy admits that. He makes the obligatory nod to Brazil, ground zero of miscegenation, in which everyone mixes and yet somehow, the elite remains white and the underclass is black. But it’s too pessimistic to say the U.S. is headed for the same fate — there’s less racial mixing here, but there’s more social mobility between classes. Intermarriage could lead to greater social equity here than it has in Brazil. We don’t know where this experiment will wind up. But one thing is clear: Interracial intimacy alone won’t eliminate racism, but efforts to stigmatize it don’t move us forward, and almost certainly set us back. The comfort in reading Kennedy’s book lies in its clarity that just like their doomed white forebears, today’s opponents of race mixing can’t win.