The children's choir at Baghdad's St. Joseph's Church soars in beseeching tones toward the heavens. "Our people are hurting, blood and tears flow from us," the children sing, "let the whole world pray with us for peace." The papal envoy, Cardinal Etchegaray, who is in Iraq in a last-ditch effort to stop the war, looks on from the front of the church. In his sermon, he has just questioned his own ability to help avert a war. "Everybody wants peace, but who still believes it is possible? How many want it with all their strength?"

While the pope was sending a seemingly hopeless message of peace, the Iraqis also received a more strident message of support. Osama bin Laden, or at least someone purporting to be him, exhorted the Iraqi people on the Al-Jazeera Arab satellite television network to stand united against the infidel. "This crusader war concerns all Muslims, whether the socialist party or Saddam remain in power or not," he said.

Rather than welcoming bin Laden's support, the regime saw in it a dangerous appeal over their heads to the people -- although in this country where satellite and cable television are nonexistent, few heard the tape firsthand or at all. "This is not for the benefit of the Iraqi people," Muthaffer Adhami, a member of parliament, rushed to say. "This is not supporting the Iraqis."

Short of divine intervention, a war seems inevitable to most in Baghdad, whatever their religion. The population has developed a certain bravura about the situation. "We have seen this all before, we have been living under sanctions and under threat for 12 years now," is a standard response. At the same time most are preparing for a war by stocking up on basic necessities. The government has handed out food rations for the next three months, and increased sales of kerosene for lamps and heaters has driven prices up. Others are trying to leave the country, or at least trying to get out of the center of Baghdad, where the heaviest bombardments are expected if war breaks out.

The country is now holding its breath waiting for the report that U.N. weapons inspectors Hans Blix and Mohammed ElBaradei will deliver to the U.N. Security Council on Feb. 14. "That day is going to decide the future of our country," says Nabila Isho at the cardinal's mass in St. Joseph's Church. She is not very hopeful the cardinal can help avoid war. "Maybe together with other people who are opposed he can make a stand. But the Americans are very determined."

The looming war even seeped into the Muslim feast of Eid al-Adha, which started on Tuesday. In one mosque in Baghdad -- like all mosques here, it is controlled by the government -- the sheik asked God in his sermon after the dawn prayers to lead the Muslims to victory and "defend his people against the unbelievers." Sheik Qoteibeh Amash at the brand new Al-Nida mosque has become something of a celebrity since he accused U.N. arms inspectors three weeks ago of having violated the sanctity of his mosque. The inspectors at the time said they were just there as tourists and that they were invited by another sheik to tour the yellow brick and blue-tiled building.

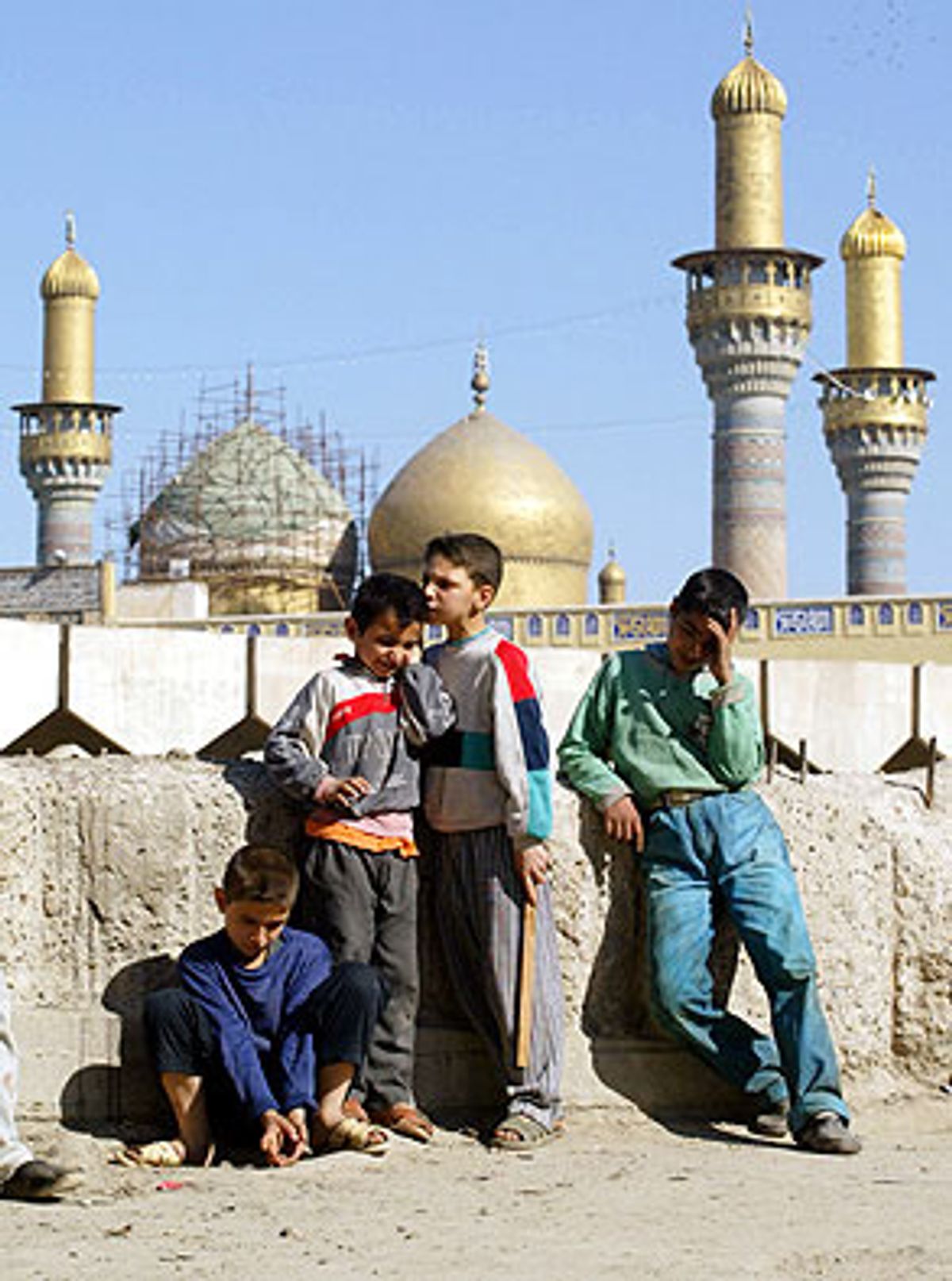

Iraq may be a secular state, run nominally along the Baath Party's socialist lines, but religion plays an important part in the lives of many. This has become more important as times have become harder, says Jawad Saad, a professor of political science at Baghdad University. "The government is not encouraging it," says Jawad, but it is clear that it is aware of the power of religion and is trying to use it for its own purposes. While there is no money for many basic services, huge amounts are spent on building new mosques. For example, the giant "Mother of all Battles" mosque in Baghdad commemorating the Gulf War of 1991 (some of its minarets are shaped like Scud missiles) opened last year at an estimated cost of $7.5 million.

This religious revival, combined with the continued hardship suffered by large parts of the population, may prove to be the biggest postwar problem for potential occupiers. "The fundamentalists will be the first to start launching attacks," says Jawad. This fits in with bin Laden's advice to the Iraqis to carry out suicide attacks if American troops enter the country. "Suicide attacks are a real possibility, why not?" says Jawad. "They may even come from secular quarters." Jawad doubts whether economic development after a possible war will mollify the people. "Nobody likes to be occupied. Nationalism is stronger than the wish for economic well-being."

That said, there seems to be very little enthusiasm among Iraqis to defend the current regime. An Iraqi political source says that "the regime is hated." Another man, who for obvious reasons did not want to give his name, predicts that "members of the Baath Party and government officials will be hunted down and killed." Baath control over the country is even now extraordinary. It goes down to the level of "districts" that consist of 30 to 40 families that are being monitored by one official. Fear of the regime and the party, which are the same, is all-pervasive and makes people afraid to speak out and certainly to resist. Nevertheless, one Western source says that many Iraqis are now saying they will refuse to fight in a new war. "They say they will stay home and if the regime wants them to fight, it will have to come and get them."

That is a far cry from the fighting talk of the purported bin Laden tape. "We are following with great concern the preparations of the crusaders to launch war on the former capital of Muslims ... and to install a puppet government," bin Laden said. "Fight the allies of the devil. I remind you that victory comes from God alone." In the streets of Baghdad, at least one soldier, visiting the monument to the "martyrs" of the war against Iran, found bin Laden's exhortations appealing. "Osama bin Laden has his views and Iraq has its views," the soldiers said. "What they have in common is that the U.S. thinks it can intimidate everyone with a big stick."

The government in Baghdad is at pains to deny any link with al-Qaida and sees the tape as a threat. "This is ridiculous," says Parliament member Muthafar Adhami. "Osama bin Laden attacks our president and the Americans still say that there is a connection between him and us." The message on the tape condemns the secular and socialist nature of the government in Baghdad but goes on to say, "Under current circumstances, there is nothing wrong in Muslim interests converging with those of the socialists in the battle against the crusaders, even if we believe and declare that the socialists are apostates." The U.S. State Department nevertheless claimed the tape showed a link between Baghdad and al-Qaida. "This does confirm that bin Laden and Saddam Hussein seem to find common cause together," said spokesman Richard Boucher.

Anti-Americanism may be on the increase now that a war is approaching, but in principle many Iraqis would like to have good relations with the United States. Khalid Ibrahim is an engineer who studied at UCLA in the 1960s. Having breakfast at home on the first morning of the Eid al-Adha, he is depressed during what should normally be a festive occasion. "I still get nostalgic when I see Los Angeles in films," he says. He could never have imagined that the country where he spent part of his youth would become his native country's enemy. He believes there is a wide gap between the attitudes of the American people and its government and blames Jewish and Zionist "pressure groups" for the U.S.'s anti-Arab policies.

Ibrahim is furious about President Bush's statement that "the game is up." He fumes, "What game? For us this is not a game -- very real lives are at stake." Some of his anger is also directed at the U.N. arms inspectors. He is a personal friend of Sheik Amash of the Al-Nida mosque and accepts his version of events about the visit the U.N. inspectors paid to the place of worship. He accuses them of not having any "respect" for the Iraqi people. He also marvels at the different tone they seem to take depending on whether they are in Iraq or abroad. That is why he is very worried about the report that the inspectors will submit to the Security Council on Friday. He fears the worst.

Ibrahim's eldest son, Walid, studies engineering and is 20 years old. "If he wasn't studying, he would have to go into the army," says Ibrahim with a hint of a shudder. Walid, wearing braces and looking the part of the computer nerd he claims to be, does not make a very soldierlike impression. His biggest worry about a coming war is that the electricity will be hit and he won't be able to work on his computer. "And at least it's not during the Eid," says Walid with a sight of relief. "They always show good movies on the TV for the holidays; I stay home and watch them all." His 14-year-old sister, Mariam, likes the boy band Westlife and the singer Britney Spears and likes to play their music. Ibrahim says that Spears should come to Baghdad as a peace envoy because of her popularity here.

At the large Al-Karkh cemetery on the outskirts of the Iraqi capital, people are less well disposed toward America. One corner is reserved for some of the more than 400 people who died in the Amiriyeh civilian air-raid shelter when American planes bombed it during the Gulf War of 1991. Iyad Abdel Khader visits the grave of his brother every holiday with his two elderly parents. A major in the army, Abdel Khader says he is not worried about the prospect of an American invasion. "I am not afraid of American soldiers. If they come here I will slit their throats. I want to take revenge for my brother."

His parents disapprove of his vehemence. "We want to live in peace with the whole world," says his mother, Widad. "We feel sorry for everybody who suffers, including the Americans."

Shares