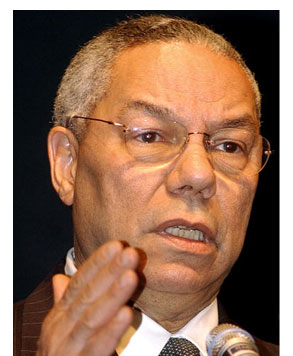

Last summer, when Colin Powell convinced President Bush that the U.S. should go to the United Nations in order to build an international coalition for a war against Iraq, the secretary of state probably never envisioned an endgame like the one that’s about to play out.

Instead of a crowning diplomatic achievement in which Powell proudly delivers to his commander in chief a unanimous U.N. resolution authorizing the U.S. to take action against Iraq, Powell is confronting a possible train wreck in which key members of the U.N. Security Council, after listening to his arguments for nearly six months, reject the American position and refuse to authorize war.

Most observers expect the U.S. to go to war whether the U.N. sanctions it or not. But that outcome would be a devastating blow to the White House, with major domestic and international repercussions. It would threaten Bush’s standing with American voters, a majority of whom polls show want the U.S. to get the U.N.’s blessing. It would isolate the United States, breeding ill-will and making the international community much more reluctant to help the U.S. rebuild Iraq. For Powell himself, it would be an embarrassing defeat that would give fresh ammunition to circling critics both on the left, who have questioned his new hawkish stance, and on the right, who doubt his competence and judgment.

Powell watching has been something of a Beltway obsession almost from the beginning of the Bush presidency. Hawks determined to go to war with Iraq, and supporters of Israel who suspected him of representing the traditional Arabism of the State Department, have long had an evil eye for the secretary of state. Liberals, for their part, have seized on him as virtually the only voice of moderation in an overwhelmingly right-wing administration. As a result, his sudden backing for the war in recent weeks has led to intense speculation about his motives and true beliefs.

Liberals and moderates who saw Powell as a stabilizing force inside the White House feel betrayed and charge he’s flip-flopped from a thoughtful, war-tested skeptic to an administration spokesperson busy peddling dubious intelligence.

“He’s no longer making objective assessments and weighing the pros and cons,” says Joe Cirincione, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the coauthor of “Iraq: What Next?” “He’s been sent out by the White House to do P.R. He has little or no control over the war policy itself. And yes, his reputation is being damaged.”

Nothing in Powell’s history suggested that he was likely to advocate a preemptive strike against Iraq. After all, it was Powell as chairman of the Joint Chiefs during the first Gulf War who stopped the fighting after just 100 hours, saying he feared among other things that the nation would split into three parts. A self-styled “reluctant warrior,” he described the Gulf War as “a limited-objective war,” adding, “If it had not been, we would be ruling Baghdad today — at unpardonable expense in terms of money, lives lost and ruined regional relationships.”

Most famously, Powell is the author of the so-called Powell Doctrine, which states that American troops should never be sent into battle unless there’s a clear strategy, including an exit strategy; that the American public must have a clear understanding of a war’s goals; and that wars should only be fought in the national interest, not for humanitarian goals or “nation building.” Today, of course, critics charge that U.S. troops are now being deployed in the Gulf without an exit strategy, and Bush has explicitly cited humanitarian goals as part of the rationale for invading.

Historically cautious, Powell for the last year has been careful not to reveal his own thoughts about the war but rather, like a good soldier, to express the views of the White House. Experts say that makes it hard to know precisely where he stands and whether he’s actually had a change of heart, is reluctantly toeing the administration’s line because he wants to exert a moderating influence from the inside, or privately thinks war can still be avoided.

“Who knows, maybe years from now in his memoir we’ll learn he was betting Saddam would back down,” says Cirincione.

If Powell was absolutely opposed to the war and felt compelled to say so, the most logical recourse would be to resign. Rumors of Powell’s departure have swirled regularly in D.C., with the latest gossip coming at the end of 2002. But with Powell’s new hawkish ways, that talk has ceased — if not speculation about what’s in his mind. “I don’t know whether it was a true transformation for Powell, or whether he thought, The most effective thing for me to do is remain on the inside where I’m still an internal critic,” says George Lopez, director of policy studies at the Kroc Institute for International Peace at Notre Dame University.

As a diplomat, Powell’s moment of truth is at hand: Matters at the U.N. are quickly coming to a head. The White House badly wants to secure a second Security Council resolution authorizing a war on Iraq, which would reassure an anxious American public and give important political cover to a key ally, British Prime Minister Tony Blair. But with France, Russia and China apparently hardening their threats of veto, Powell’s been reduced to trying to cobble together the nine votes needed to pass the resolution from among the 15 Security Council nations and leaning on the likes of Cameroon and Angola.

The diplomatic wrangling has been intense and is expected to grow even more heated in the coming days. On Friday, responding to Saddam’s declaration that he was prepared to accept the demand of chief U.N. weapons inspector Hans Blix and begin destroying prohibited missiles, Russia dealt the U.S. a setback, saying that it might veto any resolution that would hasten the use of force. For its part, the U.S. was apparently making progress in its lobbying efforts: The New York Times quoted a senior administration official as saying that he was confident that the U.S. would be able to get five of the six undecided nations on the Security Council to vote for war, giving the U.S. the nine votes required to pass the authorization. (The U.S., Britain, Spain and Bulgaria are pro-war; France, Russia, Germany, China and Syria are against it. Pakistan, Mexico, Chile, Angola, Cameroon and Guinea are undecided.)

As the chief American diplomat, Powell will rightly or wrongly absorb much of the praise — or blame — for the Security Council’s fateful decision.

Regardless of the outcome, however, many observers from across the political spectrum say that U.S. diplomacy over Iraq has been a disaster, where early U.N. victories turned out to be mirages, the international community has been fractured, and even friendly nations like Canada and neighbors like Mexico have not yet joined the coalition of the willing. The stunning setback over the weekend, in which members of Turkey’s Parliament defied government leaders and voted against allowing the U.S. to use Turkey as a staging ground for war, only added to the perception of a diplomatic meltdown.

As the possibility of a U.N. debacle looms, Powell is feeling the most heat from conservatives who are enraged that he persuaded Bush to go to the U.N. in the first place and who say the diplomatic setbacks prove he was ill-prepared to succeed. They argue the administration is spending far too much time and energy jostling with France and Russia, which in the end will likely prove futile, making America look weak.

“I do think Powell’s insistence on taking the administration and the country through this convoluted U.N. Security Council process, and having apparently no insight as to whether he’d be successful, is a huge diplomatic failure,” says Mark Levin, a former Reagan administration official and contributing editor to National Review Online.

Like Bush and Tony Blair, who have staked their political futures on a successful war, Powell could yet emerge unscathed from his difficulties. If the war is fast and relatively bloodless and the postwar period goes well, Iraq may be remembered as another triumphant chapter in Powell’s career. But if things go badly, Powell could end up vilified by all sides.

To be sure, Powell was dealt a rough hand to play. He was put in the no-win position of being the nice multilateral guy in a macho, unilateral administration whose policies and rhetoric had offended the rest of the world. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, in particular, routinely stepped on Powell’s toes by sounding off on diplomatic issues, including his notorious dismissal of erstwhile allies France and Germany as part of “old Europe.” (Spain’s Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar recently told Bush that Europe wanted to hear “a lot of Powell and not much of Rumsfeld.”) Powell’s task was especially difficult set against a backdrop in which the Bush administration had earlier pulled out of the Kyoto global-warming treaty and the international criminal court, and ignores the ban on land mines. “That cavalier policy doesn’t help to build a coalition to support American goals,” notes Jean-Robert Leguey-Feilleux, a professor of political science at St. Louis University who teaches about diplomacy and the Middle East.

Also, Powell’s inability to moderate what most Europeans see as the administration’s stridently pro-Israeli position in trying to mediate the Middle East conflict has hurt his credibility overseas.

Still, anything is possible at the U.N., and the U.S. putting its full force behind an international policy has a way of altering the dynamics. “One thing you do learn about American influence: Its application changes the odds,” notes Leon Furth, a former national security advisor for Vice President Al Gore.

White House officials like to stress that last November it counted only seven votes of support for what became U.N. Resolution 1441, which signaled the return of weapons inspectors to Iraq. Yet after weeks of tenacious diplomacy, that tough resolution passed unanimously, 15-0. At the time it was toasted as a miraculous diplomatic achievement. Bush praised Powell’s “leadership, his good work and his determination” in securing the vote, while Fox News reported that the unanimous passage was “almost a miracle.”

But in truth there was less than met the eye to Powell’s triumph. Within hours of 1441’s passage, French and American diplomats were coming to drastically different conclusions about what it meant. The U.S., lead by Powell, argued the resolution clearly stated that if Iraq was found to be in “material breach,” then the administration was authorized to wage a war, with or without additional U.N. approval.

The insistence all along by France, Russia and China was that the resolution could not contain a “hidden trigger” allowing the U.S. to unilaterally declare war in the name of the United Nations the moment that Washington, and not the Security Council, deemed Saddam in “material breach” of the inspection regime. Powell’s diplomatic counterparts wanted to make sure after the resolution passed that they still had a serious say in a possible war and that the White House still had to work through the U.N. in search of a second resolution.

At the time of its passage, Powell’s team at the State Department seemed confident that inspections would produce clear Iraqi obstructions on the ground and that the Security Council would vote out a second resolution authorizing a U.S.-led invasion. “Clearly that hasn’t happened,” says Christopher Preble, director of foreign policy studies at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington.

“I think Colin Powell is as surprised as everybody else that France would stick its finger in our eye and that Russia has been so difficult,” says Levin. “But he’s paid to know these things and you’d think he would have had a better plan.”

Leguey-Feilleux at St. Louis University adds, “1441 was a fig leaf. And that’s exactly what Powell’s looking for now: another U.N. fig leaf.”

Obviously Powell wanted more and hoped his crucial Feb. 5 presentation to the U.N., in which he laid out in detail allegations of Iraq’s noncompliance, would lay the groundwork for a successful second resolution. The White House, knowing Powell was the most respected member of the administration, hoped it would put to rest any lingering doubts about the need for war. Instead, it signaled a brief high-water mark; within days, key elements of the presentation began to unravel amid charges of plagiarism and exaggeration, which quickly undercut any goodwill Powell had won.

“There has always been the impression that within the administration Powell was more thoughtful and restrained and that when he spoke people would believe him. But that hasn’t happened,” says Preble. “And the next time he makes a case, whether it’s on North Korea or NATO, people will say he tried to make a case with Iraq. Whenever you expend political capital and it doesn’t work, there is a cost.”

Initially, Powell’s presentation went over well at home. “He performed rather well,” says Ken Stein, professor of Middle Eastern history and political science at Emory University in Atlanta. “He was articulate, straightforward, and he had terrific evidence.”

Writing in the Chicago Sun-Times, Mark Brown noted that, “By tapping into Powell’s immense credibility, the president knocked out most of the last remnants of opposition in the Congress for his preemptive war.”

But the secretary of state’s primary objective was to convince allies overseas, not members of Congress across town from the White House. And in the end, American politicians, along with a few centrist and left-leaning columnists, seemed to be the only ones Powell really impressed.

“He persuaded me, and I was as tough as France to convince,” wrote Mary McGrory in the Washington Post.

But a strange thing happened between Feb. 5 and Feb. 14, when the Security Council reconvened and heard an updated presentation from chief weapons inspector Hans Blix (followed immediately by a weekend of global antiwar protests); Powell’s diplomatic momentum completely stalled; in fact, it suffered a series of setbacks.

Although Americans hold Powell in high regard — by a 3-1 margin they find him more trustworthy than Bush when it comes to the war– most people did not change their mind about the need to wage war in the wake of his highly publicized U.N. presentation.

Even in conservative Alabama, where Bush won easily in 2000, a statewide poll — taken two weeks after Powell urged the U.N. to take swift action — found a majority of people thought that weapons inspectors should be given more time and that Iraq did not pose an immediate threat to America.

Over time, even some of those sympathetic, left-leaning D.C. pundits began retracting their glowing reviews of Powell’s Feb. 5 presentation. At the Washington Post, William Raspberry first wrote, “It was a spectacular performance, and by the time Colin Powell was finished, I was a complete convert.” Last week he changed his mind about Powell: “I don’t believe him.”

Of course, Powell’s biggest problem may have been simply that he didn’t have strong enough evidence but as a good team player had to go out and do his best anyway. The alleged links between Saddam and al-Qaida, for example, are extremely tenuous. And absent corroborating evidence, many of the intelligence-based claims about suspicious Iraqi behavior had to be taken on faith.

But critics say that Powell made things worse by not working wavering countries hard enough and by pumping up dubious claims.

Powell’s distaste for globe-trotting is well known. In his 1995 memoir, “My American Journey,” he wrote, “Having seen much of the world and having lived on planes for years, I am no longer much interested in travel.”

Between September 2002 and mid-January 2003, the secretary of state did not make a single solo trip outside the Americas. And during that period he visited just seven countries, and three of those — Mexico, Canada, and Colombia — were not overseas.

Contrast that with the journeys of former Secretary of State James Baker, who was in charge of putting together an impressive fighting coalition for the first Gulf War. Between August 1990 and January 1991, he made eight separate trips overseas and traveled to 18 international capitals to meet with leaders. He visited some key allies more than once: Saudi Arabia five times, for example, and Turkey three times.

Powell’s decision to stay home during the crucial diplomatic stretch between Feb. 5 and Feb. 14 may have been a mistake. Because while he was working the phones, Russian, French and German leaders were engaged in vigorous shuttle diplomacy, jetting off to each other’s capitals for face-to-face discussions about the war. Whether Powell could have done anything to avert the French-Russian-German opposition is uncertain. But by Feb. 14 — when Blix gave a surprisingly upbeat report to the U.N. on Iraqi compliance and France’s foreign minister, Dominique de Villepin, won rare applause inside the U.N. when he declared that the case for war had not been made — the diplomatic tide had decisively turned.

Trying to reverse that tide, a clearly frustrated Powell set aside his prepared statements on Feb. 14 and spoke from the heart about the need for the international community to finally meet its responsibility to disarm Saddam, by force if necessary. “We cannot wait for one of these terrible weapons to turn up in our cities,” Powell declared. “More inspections — I am sorry — are not the answer.” But his plea had no lasting effect on shaping opinion inside the U.N. or out.

Nor was Powell able to rebut critics who found troubling holes in the intelligence he presented to the U.N. For instance, Powell spent significant time detailing an al-Qaida-run poison-making terrorist camp near the village of Khurmal in northern Iraq. But neither Powell nor the White House could answer the obvious follow-up questions: What was the United States doing about the camp, and why hadn’t it already been bombed by U.S. military jets that have been flying daily recognizance missions over Iraq for years?

As part of his U.N. brief, Powell cited an “exquisite” British “intelligence” dossier that detailed Iraq’s deceptive practices. Within days though, it became clear the report, which contained information that turned out to be 12 years old, had been put together by Blair’s press office and had plagiarized key sections from a graduate student paper available on the Internet.

Powell’s gaffe received minor play at home, but it was a major story overseas, particularly among the British public, and it seemed to fortify suspicions about the United States’ rationale for war.

And then, breaking the news about a new audiotape from Osama bin Laden, Powell told members of Congress it would prove a connection between al-Qaida and Iraq and warned: “This nexus between terrorists and states that are developing weapons of mass destruction can no longer be looked away from and ignored.”

Some Americans — many of whom confuse bin Laden and Saddam Hussein — may have believed this claim, but it was alarmingly crude. On the tape bin Laden dismissed Saddam as an “infidel” and “socialist” and told the Iraqi people it didn’t matter whether their illegitimate leader lived or died — words that made Powell’s fear-mongering less than convincing.

“People are sophisticated about this and they understand Saddam Hussein and al-Qaida have different priorities,” says Preble. “I think Powell overreached trying to make the linkage and he’s taken a hit because of it. His credibility has been damaged.”

Some longtime admirers suggest Powell’s credibility has also been damaged by his apparent change of heart about war. They wonder what happened to the skeptic who just weeks after the al-Qaida terrorist attacks on America, told the New York Times: “Iraq isn’t going anywhere. It’s in a fairly weakened state. It’s doing some things we don’t like. We’ll continue to contain it. But there really was no need at this point, unless there was really quite a smoking gun, to put Iraq at the top of the list.”

The fact is, prior to Sept. 11, it was Powell and his staff who were working the hallways at the U.N. trying to garner support for so-called smart sanctions against Iraq. Instead of tightening the loose around Saddam, these would have dramatically eased the restrictions on goods flowing into the country.

And then there’s the Powell Doctrine, which “he’s conveniently ignored,” says Cirincione at Carnegie. A Vietnam veteran who was frustrated by how the war was conducted and how it was perceived at home, Powell in an early ’90s Foreign Affairs article, set out key criteria that must be met before the U.S. commits its troops to war. They include using overwhelming force, identifying a clear political objective, including an exit strategy, and having the support of the American people who are clearly informed about the war’s strategy and goals.

With approximately 225,000 troops expected in the region, overwhelming force will clearly be applied in Iraq. But Cirincione doesn’t think Powell has articulated an exit strategy or the war’s goals. “The whole point of the Powell Doctrine was to avoid future policy disasters,” he says. “We’re about to engage in a radical [preemptive] experiment that violates most of Powell’s previously held beliefs. Either he was wrong 11 years ago when he [wrote] the Powell Doctrine and he should tell us, or this president is leading the country into a disaster.”