In Steven Soderbergh's "The Limey," a beautiful young woman says to her boyfriend, a rich, aging '60s hotshot -- played with perfect desiccated glamour by Peter Fonda -- "You're not a person; you're more like a vibe." Writer-director Lisa Cholodenko's "Laurel Canyon" may be more a vibe than a movie. And that's precisely its power.

In some ways "Laurel Canyon" feels more attuned to the laws of music than the laws of movies: Cholodenko is interested in her characters first and foremost, but the spaces between them are a close second. And how do you film spaces? Cholodenko and her actors pull it off; the performances here are like a wary ballet, ruled as much by the mysterious magnetic attractions and repulsions these characters feel for one another as by anything so dully explicable as psychology or standard rules of social conduct. In "Laurel Canyon," the beats between the notes are as crucial as the notes themselves.

Frances McDormand plays Jane, a longtime record producer in her mid-40s who still lives some semblance of the life she lived in the late '60s and early '70s. She smokes pot, she drinks, she hangs out with (and sleeps with) beautiful young rock stars, among them her current flame Ian (Alessandro Nivola), the lead singer of the English rock band she's trying to break in the States. She's supposed to have finished work on the band's album before her straight-arrow psychiatrist-in-training son, Sam (Christian Bale), is to arrive at her Laurel Canyon home with his fiancée and fellow academic, Alex (Kate Beckinsale).

Sam is attending a training program for psychiatrists; Alex is working on her thesis (some genetic business involving fruit flies). Jane has told them they can stay at her house, which she has promised will be vacant by the time they get there -- that's crucial to Sam, who seems to love his mother but has little patience for what he sees as her disorderly and unfocused lifestyle.

But Jane's unfinished work means she can't leave, and so she, Sam, Alex and Ian settle into an uneasy cohabitation as the rhythms of the household shift and change around and between them. "Laurel Canyon" is primarily about sex, although not in the most obvious way. The shy, quiet Alex, who at first thinks she's perfectly happy holed up in her room going through reams of fruit-fly data on her computer, realizes that she likes hanging out in the studio with Jane and the band.

Beckinsale works the transformation convincingly, simply by showing it's not a transformation at all. She's not your typical straight girl aching to go wild, but, rather, a serious girl who suddenly recognizes that her sensible, sterling character doesn't preclude sexual adventurousness -- particularly given that Sam, whom she loves and thinks she's happy with, treats sex as if it were something of an obligation.

At least sex with her, that is. Sam is more stolidly serious than Alex is, about his work and the stringently planned configuration of his life; that's obviously a reaction to his mother's highly annoying free-spiritedness. Sam is so straight that he's almost unlikable, and Bale, always a wonderful actor, plays him so he brings us just to the point of impatience with him. But it's evidence of Cholodenko's love and compassion for her characters that Sam is never made out to be the villain.

As narrow as Sam seems to be about sex, he can't resist the burgeoning attraction he feels for a fellow resident at the hospital, a lush, brainy Israeli doctor-in-training named Sara (played by the magnificently doe-eyed Natascha McElhone). Together they have one of the best and most delicate scenes in the movie, one that suggests that the possibility of connection (sexual and otherwise) is still wholly open to Sam, even though he seems to rail against "connection" as a false, airy '60s construct. It's the movie's most sensual scene, although the two of them do nothing more than talk.

And so the characters conjoin and disentangle in various weird permutations, some of them brief and wholly asexual, others distinctly charged with eroticism. Ian is devoted to Jane, and she loves him back, though it's not her style to hold on too tight -- she's more likely to cuff him as if he were a lion cub. But Ian nevertheless finds himself intensely attracted to Alex, and he flirts with her mischievously. As Nivola plays him, Ian is like a rock 'n' roll emissary on a special mission from England to spread joy and delight among the female population of America, leaving everyone happy and satiated and not the least bit jealous of one another -- he's a flesh-and-blood embodiment of the '60s ideal that few people who actually lived in the '60s could ever pull off.

McDormand's Jane is the locus of these mutable, ever-shifting interconnections. One of the most refreshing things about "Laurel Canyon" is that it doesn't present sex as a novelty enjoyed only by young people. Nor does it work overtime to tout the fact that its lead character is a sexually potent woman past the age of 40. Jane, as McDormand plays her, simply is, and that's what makes the performance so marvelous.

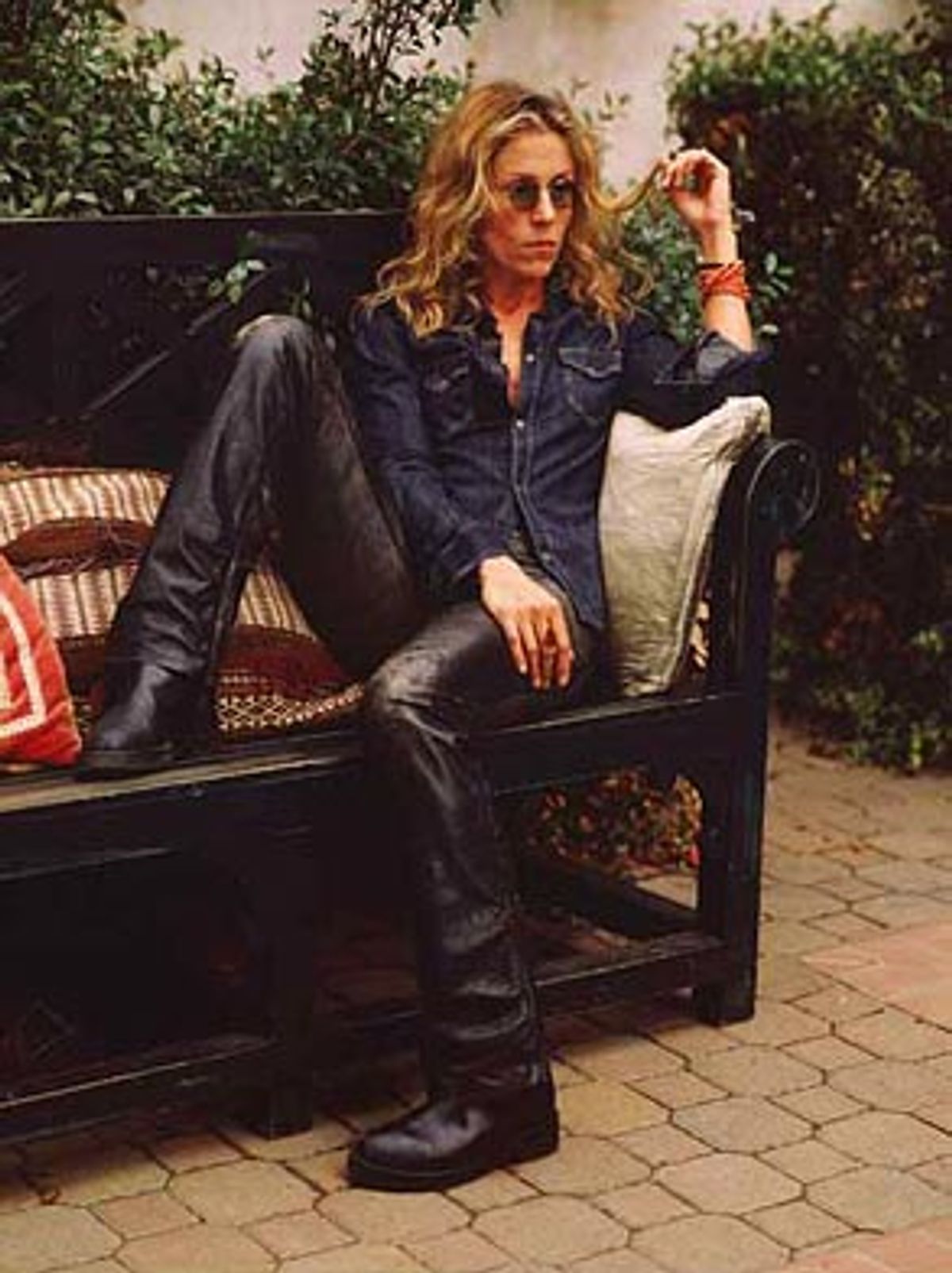

Jane isn't one of those characters who clings to her past to the point of ridiculousness; instead, she moves forward through the decades while wholly accepting how her past has shaped her. She struts through the movie in worn concert T-shirts and sleek leather pants, but they never come off as youthful affectations -- she looks as comfortable (and as sexy) in them as if she were wearing PJs.

McDormand has perfected the art of the lived-in performance. She's astonishingly beautiful here, as well as youthful-looking, not because her skin is perfect or her hair is spectacular, but because everything about the way she moves, about her expression, gives the sense of a woman who's looking constantly forward rather than back. She doesn't play Jane as the older woman who's lucky to have landed a cute young guy; all that's clear is that she's got something he wants, something wholly desirable -- her aura of confidence is the most charismatic thing about her.

The movie's dynamic, its sense of momentum and energy, comes from the way Cholodenko and her actors toss out all the crapola that we've been programmed to believe about aging, sexuality, about just plain living. Jane is as vulnerable, and as flawed, as any other human being, but the last thing she's interested in is actually becoming her flaws. (The movie's one misstep is a speech Jane gives at the end, where she apologizes to Sam for not having been the world's greatest mother. Jane's confession is unnecessary because there are plenty of moments in McDormand's performance where she shows, either through body language or just a brief, mournful glint in her soft brown eyes, that she's fully aware of where she's fallen short.)

"Laurel Canyon" isn't a tremendously funny movie, yet Cholodenko infuses it with great good humor. Her first feature, "High Art," was skillful and intense, but "Laurel Canyon" throws off a much more seasoned, relaxed confidence. I can't recall a single line in the picture that made me laugh out loud, and yet I recall almost the whole movie as unrolling with ease and affection and liveliness, even amid the weird tensions and heartaches of the characters. Wally Pfister's cinematography suits the movie's mood perfectly: This isn't a harsh, garishly lit Los Angeles, but a cautiously romantic one that's still dusted with the shimmery dust motes of old Hollywood -- those hardy, luminous little things that have survived decades of rising and falling starlets, big-money movie deals, rock 'n' roll excess and all sorts of dashed dreams.

The characters in "Laurel Canyon" do unorthodox things that are sometimes a little startling. Yet those moments are always brushed with tenderness, as opposed to selfishness. Cholodenko neither romanticizes nor demonizes her characters' unconventionality. All she seeks is to show us is that to get through life, it's simply necessary to find a way of living -- a quest that means much more than striving toward a certain lifestyle or a specific job. Her "Laurel Canyon" is a pure L.A. movie, in its look, sound and feel. The West Coast used to represent the place you'd go to find yourself. But Cholodenko's L.A. is a state of mind, a wave of movement and sound that you could feel as acutely on the Alaskan tundra as in the Hollywood hills. Good vibrations always travel.

Shares