When a director includes a quote like "I read Proust every day. I'm one of those who marks life 'Before Proust' and 'After Proust,'" in the press material for his new film -- and when the director is William Friedkin and his new movie is "The Hunted" -- it's almost too easy, too cheap a shot to use the quote against him. But when a filmmaker invokes Proust and then offers up something as bloody and disagreeable as "The Hunted," he's got only himself to blame.

There is a Proustian madeleine in "The Hunted," and fittingly, it comes right at the beginning -- a nighttime sequence, set in 1999, during the fighting in Kosovo, in which we see Serbian soldiers slaughtering civilians while U.S. forces slither covertly through the carnage, trying to locate and kill a Serbian officer. We see bloodied corpses, their faces frozen in distorted agony, children screaming as their parents are flung into pits of bodies and machine-gunned and, in a shot that sets some new standard for shamelessness, a little girl wandering through a room of murdered civilians and picking up her stuffed animal from beside the body of her dead mother.

It's not any of the people on-screen but the audience for whom this sequence initiates a Proustian moment, reminding us of what a lousy time we've had at previous Friedkin pictures. In movies like "The French Connection" (a vastly overrated and largely incoherent film) and "The Exorcist," Friedkin seemed to have nothing on his mind but pounding the audience. He has no affinity for humor, nor is there any artfulness or brutal lyricism in his violence. Friedkin is grimly determined to deliver the shocks, and to present them not as the pulp exploitation they are but as weighty issues being handed down to us in stone.

Thus "The Exorcist" was about the battle between good and evil, and "The Hunted" is about the cost of battle. And just to make sure we get the 10-ton heaviness of it all, the beginning of the movie gives us the voice of Johnny Cash, coming out of the darkness like an Old Testament scourge, reciting the opening verse to Bob Dylan's "Highway 61 Revisited" ("God said to Abraham, 'Kill me a son...'").

One of the American soldiers we see in the opening sequence is Aaron Hallam (Benicio Del Toro), a Special Forces assassin who, the movie tells us, has been so efficiently trained that he can't stop being a killing machine. After the opening in Kosovo, "The Hunted" skips forward to the present day, where Hallam, living out in the woods of the Pacific Northwest, slaughters a pair of hunters he believes are after him.

Essentially, the script, by brothers David and Peter Griffiths and Art Monterastelli, offers us Rambo as a psycho. (I'm thinking of the original Rambo movie, "First Blood," efficiently directed by Ted Kotcheff, which was considerably different from the ones that followed.) Hallam's former instructor (Tommy Lee Jones), now retired and working as a tracker for a wildlife fund in British Columbia, is the only one who can stop him.

There's no reason the movie -- after beginning with Hallam killing those hunters -- couldn't have covered the "psychology" of the character (his battle experience in Kosovo as the thing that unhinged him) in a few lines of dialogue. But that way Friedkin wouldn't get to stage his big battle sequence with all those exploding mortars, camouflaged soldiers, bloodied corpses and terrified children. And you have to ask, what's in the mind of a director who uses genocide as a cheap explanation for an overblown action picture? Is there anything more sordid?

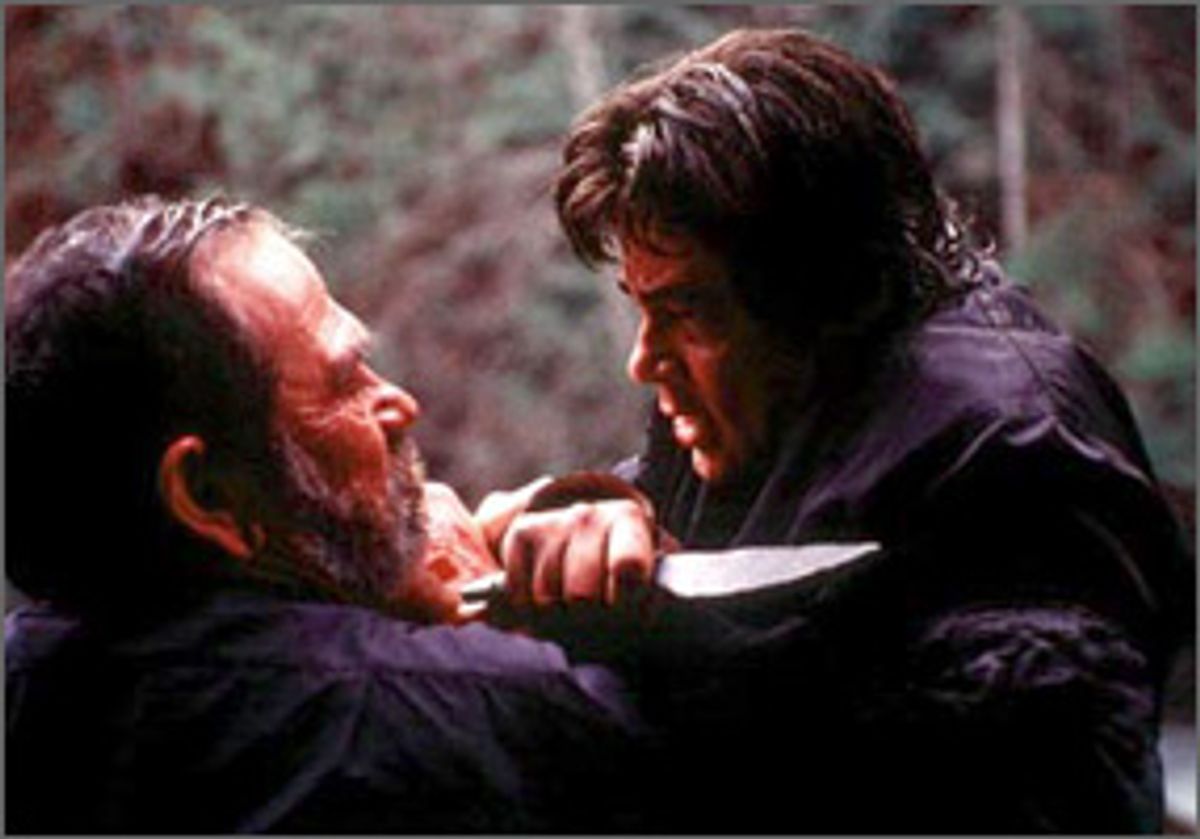

What follows is Jones' L.T. Bonham on a manhunt for Del Toro's Hallam. Inevitably, the trailer for "The Hunted" reminds us that both Jones and Del Toro are "Academy Award winners." So what do these Academy Award winners get to do? Basically beat each other silly and, in the climax, slice each other up with a pair of knives made of stone and scrap metal that the two have used their survival skills to craft. Friedkin doesn't miss any chance to show us knives slicing open flesh or going through limbs -- and you just know he'd justify his choices by some nonsense about not shying away from the ugliness of violence, which has long been the favored defense of brutalists (and their critical champions) when they want to cloak exploitation in serious intent.

But the violence in "The Hunted" doesn't illuminate the characters, who are both thimble-deep, and it doesn't make us reflect on the cost or nature of violence. It just makes you despise Friedkin and the writers for reducing a serious subject to cheap, nasty jolts. This isn't a movie made for an audience likely to be interested in that subject, but for moviegoers who get off on the brutality. It's an A-list movie for the most brain-dead elements of the action-movie crowd.

Cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, one of the great contemporary directors of photography, whose credits include "The Black Stallion" and "The Right Stuff," is better than this tripe deserves. There are some lovely views of the snowbound Canadian wilderness, and a striking shot of Del Toro's face briefly visible under a waterfall as Jones stands on the other side. Connie Nielsen, in the role of an FBI agent, is on hand with nothing to do except lend her usual sane, warm, believable presence (which is at least something in a movie this empty).

Nielsen has the movie's best scene, a casual interrogation of L.T. in which she tries to get him to talk about his past. Jones' monosyllabic answers feel both casual and considered, the tossed-off responses of a man who does not like to talk about what he's done. It's the only real acting anyone gets to do in the movie, and it makes it all the more depressing that moviemakers can't seem to conceive of anything for Tommy Lee Jones but these brooding, silent man-of-action roles. Del Toro gives a muted version of a bughouse performance. (When he turns up at the house of a woman he was dating, gives her little daughter an impromptu tracking lesson, and goes into a spiel about how men don't respect the animals they kill, you wonder why she ever let this guy near her kid in the first place.)

I'm not against violent movies, or even against violent action movies, of which I've enjoyed more than my share. Much of what excites audiences at action movies is less the pain and suffering caused by violence than the visceral charge of action. I don't think there's anything inherently immoral in divorcing violence from pain if the cost of violence is not your subject. Putting violence in the realm of fantasy -- knowing that the guys Jackie Chan kicks to the ground are going to get back up or, in the climax of a Bond movie, showing three bad guys doing midair somersaults after an explosion instead of showing them writhing on the ground in pieces -- can be a way of reminding us that what we're seeing is not real. There's a sort of morality, or at least a respect for the audience, in an action movie that chooses kinetic movement over sadism and pain.

What I am against are thrills pretending to some higher purpose, especially when the thrills have the sustained sadism of the violence in "The Hunted." I think I'd feel the same way about "The Hunted" at any time. But when we're facing war and when the threat of terrorism remains very real, when people, no matter what side of these issues they're on, feel their gravity and recognize that we can no longer feel divorced from events taking place far away, it's especially offensive for a movie to make such cheap use of violent events. The alienation Friedkin shows from the anxious mood of the country -- the message he sends here that anything can be fodder for a crummy action picture -- is one of the more monstrous pieces of egotism the movies have shown us lately.

Shares