Somewhere in the film critic's code of ethics it says that you're not supposed to give obscure foreign movies a break just because they're interesting and informative, and open windows on parts of the world you know little about. So you should know that the Iranian film "Under the Skin of the City" (playing now in New York, with other cities, perhaps, to follow) might not rock your world with post-post-Tarantino camerawork or revolutionary narrative technique or anything.

But this solidly made and sometimes quite moving chronicle of a working-class family in Tehran is nonetheless an important movie for Americans to see. It's told in a low-key semi-documentary style, by a woman director who is in fact one of Iran's leading documentarians. Furthermore, of all the Iranian films I've seen in the last few years, "Under the Skin of the City" offers the most searching and complicated portrait of that nation's rapidly changing society. It's that society, we might add, that some of the creepy, overfed dudes behind the scenes of United States foreign policy would like to bulldoze and fill up with shopping malls after they get finished in Iraq.

Mind you, as director Rakhshan Bani Etemad's consistently fascinating journey through the gray-market work world of Tehran reveals, the malls are already there. As in Abbas Kiarostami's quite different but equally worthwhile new film "Ten," Tehran emerges as a city of SUV-clogged highways, glass-fronted shopping centers and high-rise office buildings. (I suppose we should all know that already, but I'm guessing we don't.) Yeah, the family in "Under the Skin of the City" lives in an older, Middle Eastern-style stone house built around an open courtyard. But they go out to eat at an '80s-looking pizzeria that's straight out of suburban California, complete with uncomfortable steel chairs and a wait staff in butt-ugly polyester uniforms.

As a filmmaker, Bani Etemad is closer to the European "neorealists" of the postwar period, like Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini, than to the philosophical and linguistic explorations of Kiarostami, Iran's most famous film export. She offers the familiar neorealist mix of downbeat melodrama and working-class domestic comedy: A long-suffering mom, an ineffectual, puttering dad, rebellious kids with radios and motorbikes. Overall, in fact, the social dynamic depicted here is strikingly similar to that of Europe in the '50s: We see a society grappling with rapid liberalization on one hand and the resistant forces of tradition -- religion, nationalism, patriarchal family structure -- on the other.

Tuba (stage and screen veteran Golab Adineh), the family matriarch, battles to save her cozy home from the vague financial schemes of her hapless, disabled husband (Mohsen Ghazi Moradi). Eldest son Abbas (Mohammad Reza Foroutan) dreams of getting a visa to go work in Japan, and so pull the whole family out of poverty. Working as a messenger and gofer for various shadowy businessmen, he gradually gets roped into fulfilling the kind of illicit errand that never goes well in a movie like this. (You know: "All you have to do is drive this truck to the border -- it's no problem!") Younger son Ali (Ebrahim Sheibani) is some kind of unspecified student activist, although in the Iranian context it's probably clear that he's agitating for democracy and against the regime of the Islamic mullahs.

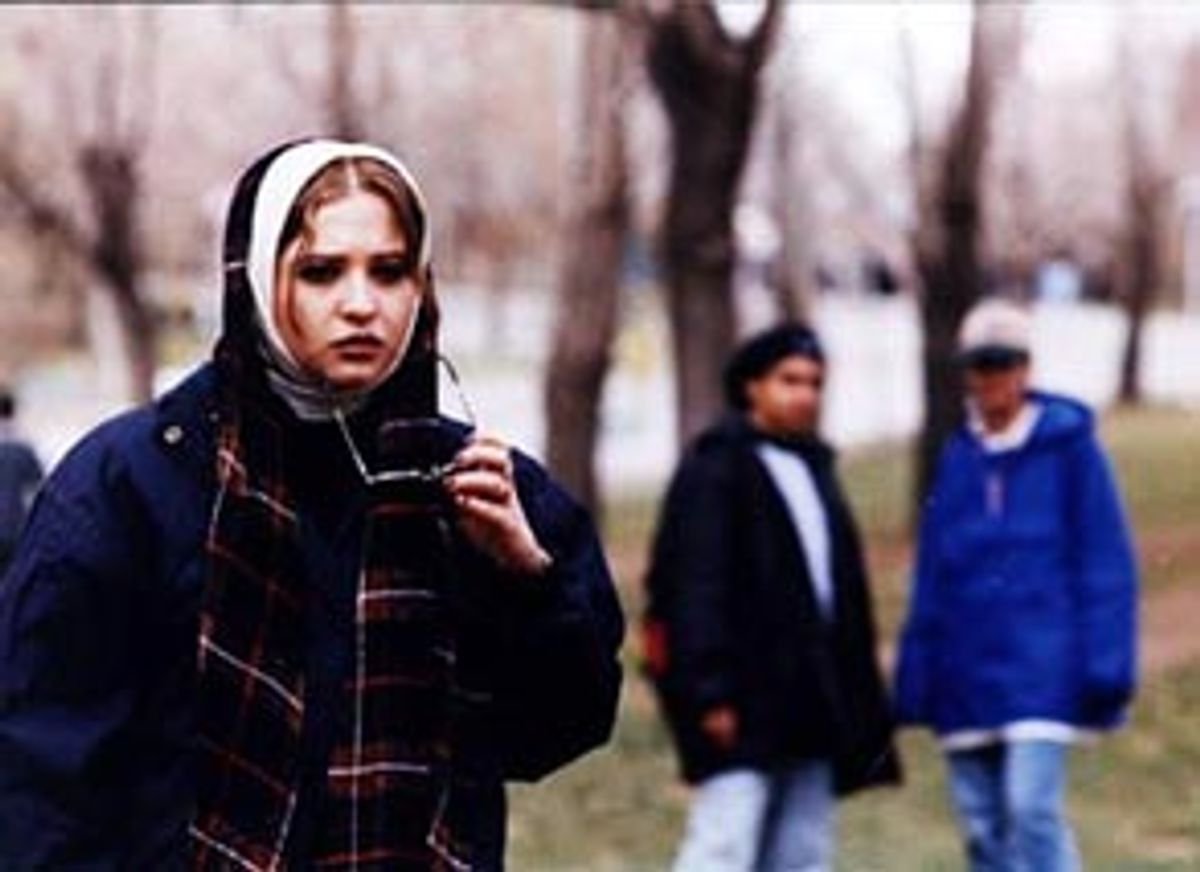

Although doomed Abbas and stoical Tuba clearly form the dramatic centerpiece of the film, Bani Etemad's heart may well be with Mahboubeh, the family's daughter. (She is played by Baran Kowsari, who is in fact the director's daughter.) All the acting in this movie, as in most contemporary Iranian films, is quite skilled. But Mahboubeh is less a "type" than the other characters, and more an ordinary, mischievous and perennially exasperated teenager who wants to go to rock shows, gossip about boys and pass notes over the wall to the girl next door.

Not long ago, Iranian films had to work around government censorship through indirection and allegory (which some critics have cited as a source of the medium's extraordinary flowering in that country, as in the old Soviet Union). But scripts are no longer subject to prior approval, and Bani Etemad simply refused to make any of the changes censors demanded in "Under the Skin of the City." We see a woman without her head scarf (as in "Ten"), we see a prostitute out in public (ditto) and we see male and female characters dancing in the same shot, all things that would until recently have been impossible.

In one of the pseudo-Brechtian moments with which Bani Etemad begins and ends the film, Tuba pauses amid the tragic denouement to berate the camera: "Who do you show these movies to, anyway?" Well, to the whole world, I hope.

"Under the Skin of the City" clearly signals a new directness in Iranian society; it's openly critical of both Iran's "Eastern" and "Western" failings. It takes on paternalistic Islamic rule and the continuing oppression of women (the scene of schoolgirls playing volleyball, shrouded head to toe in black, is especially eloquent) as well as the pell-mell infusion of capitalism that has led to widespread crime and corruption. It was also Iran's top-grossing movie of 2001, and was voted the best film that year by Iranian critics. If one can draw political conclusions from a movie, this one suggests that Iranians are more than capable of addressing their own problems. If God, Allah and Richard Perle are willing, we will leave them alone to do just that.

Shares