Even before the nation went to war, one of the most persistent criticisms that Europeans, especially the French, leveled at President Bush is that he is a cowboy. Part of this is just an elaboration on the president's boots, twang and down-home manner, all of which suggest the anti-intellectualism that Europeans abhor in Americans. Another part is an elaboration on the western myth itself, or at least on how Europeans interpret it. The president appears cocksure and reckless, always ready to draw his guns and shoot. It is, in truth, an image the president seems almost eager to cultivate. He has warned in western lingo that we would get Osama bin Laden dead or alive, that some missing al-Qaida operatives aren't ever going to come back, and that Saddam Hussein had 48 hours to get out of town.

"The notion that the president is a cowboy -- I don't think that's necessarily a bad idea," Vice President Cheney recently remarked on "Meet the Press."

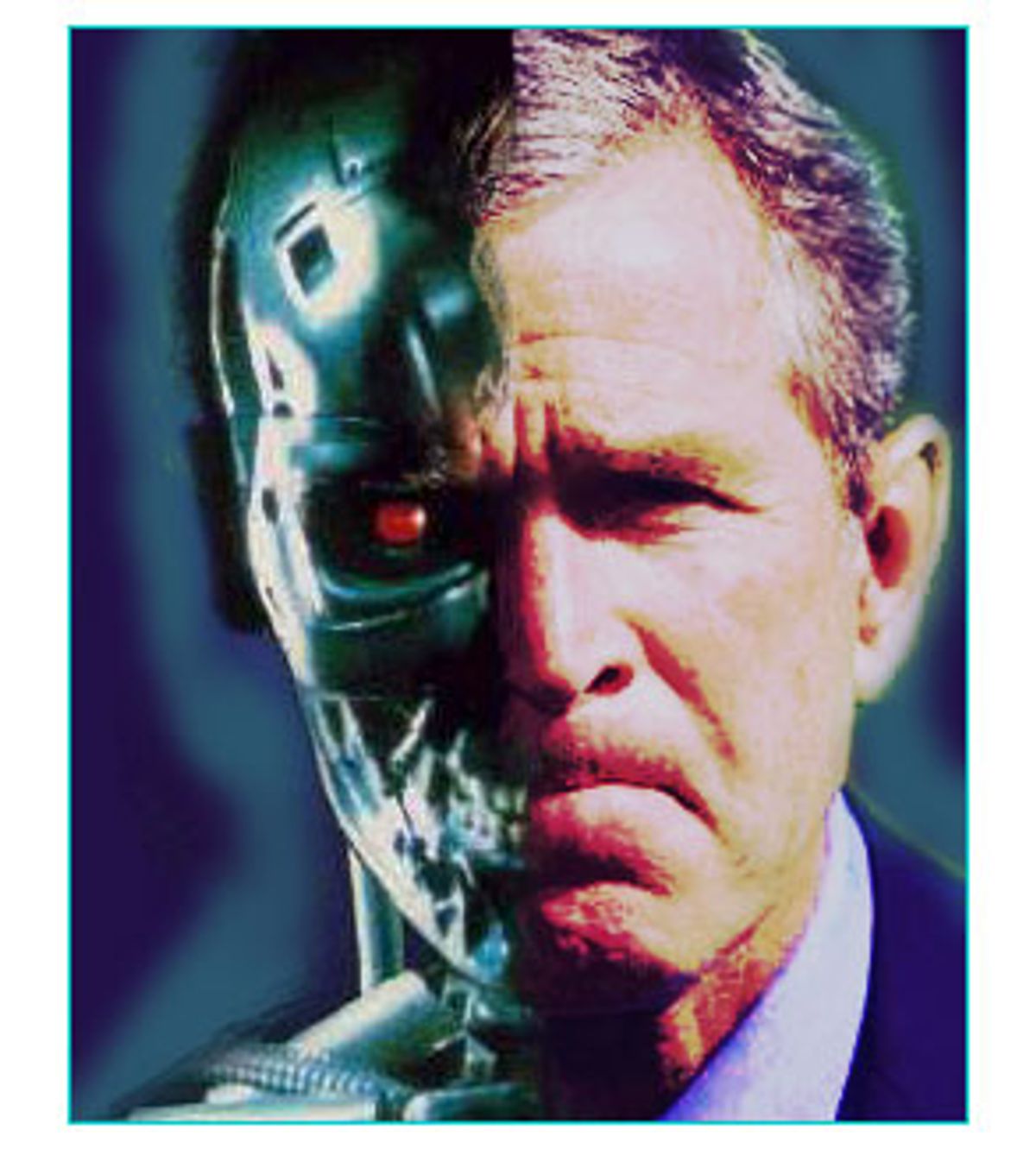

In invoking the cowboy, the Europeans are right to think that images matter, that they can penetrate the national consciousness, and that they can shape how the country conducts itself. And they are right that the president and his posse often do behave like a bunch of gunslingers who seem to love frontier brinkmanship. But in a much deeper sense, the Europeans are wrong, largely because they don't really understand the western and its values. As much as Bush may look like a cowboy and act like a yahoo, his foreign policy generally, and the Iraq war specifically, are actually a dramatic departure from the paradigm of the dour, sensitive gunslinger that for generations seemed to serve as a kind of template for American conflict. Under George W. Bush, America is no longer a cowboy nation. It is more like a cyborg nation with a brand-new paradigm -- not the cowboy but the Terminator, the robot from the popular films of that name. Call it Pax Schwarzenegger.

As the Europeans caricature the cowboy, his signal characteristic was that he shot first and asked questions later. Nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, the idealized cowboy of our westerns was always under control and never acted precipitously, preemptively or wildly. It was the gangster who sprayed his machine gun indiscriminately, the gunfighter who made his bullets count. More, the cowboy never chose to fight and certainly wasn't eager to do so. A reluctant warrior, he usually had to be goaded into battle, breathing a heavy sigh as he finally strapped on his guns and lumbered down that dusty street. As the critic Robert Warshow described it in his classic essay "The Westerner," "[T]he drama is one of self-restraint: the moment of violence must come in its own time and according to its special laws or it is valueless."

If anything, this image both reflected and informed the country's deep isolationist impulses -- impulses that prevailed right up until Pearl Harbor. As a nation, we didn't hanker to get involved in someone else's fight. We weren't quick to anger. "No American blood for Europe" was one of the isolationist rallying cries after the German invasion of Poland. It was only when we were drawn upon that we knew we had to draw ourselves. We were reactive rather than proactive, though sometimes, as in Vietnam, we thought we were being threatened when we weren't. When we did enter a fight, there wasn't much joy in it and, despite President Wilson's crusade in World War I to "make the world safe for democracy," seldom a sense of higher moral mission. "A man's gotta do what a man's gotta do," was the cowboy's pragmatic motto. In a way, it was the nation's motto too. There was no such thing as a war of choice, no saber rattling, no conceivable alternative to fight, only the sad recognition of the inevitability of violence and the resigned acceptance to use it.

In the western, and in warfare, this reluctance was less a function of the gunman's caution than of his humility. He was clearly a moral figure who believed in his cause, which typically was to defeat the villains, and establish a democratic order; yet his code was instinctive, not ideological. He appreciated complexity and difficulty, and he realized that no matter how noble the end, the outcome was never certain. (In fact, the concept of "mutually assured destruction" that framed defense policy during the Cold War was really nothing more than the idea of two gunfighters facing each other down, knowing each could be killed in the fight.) As a result, cowboys didn't swagger or vaunt. They exuded a quiet confidence rather than arrogance.

Perhaps, above all, there was always, in the best and most enduring westerns, a tragic dimension. The cowboy was fighting to facilitate a social order and a civilization of which, poignantly, he knew he could never really be a part because he was, by temperament and profession, outside its boundaries. He did his job and left. He also understood that when one assumes the obligation to vanquish evil, one must sacrifice one's own personal comfort and gratification.

Look closely at the films of John Wayne. What one sees is that Wayne must always choose between his duty to society and his personal desires, especially the desire for a family, which is why Wayne is usually alone in these films. (His best movie, "The Searchers," is partly about this sacrifice.) This accounts for the weariness one often feels in the western hero -- that stern, sad countenance, and that slow gait that seem so much a part of the national iconography. American soldiers often have the same look and attitude. It is a form of virtue. As Warshow put it, "The Westerner is the last gentleman, and the movies which over and over again tell his story are probably the last art form in which the concept of honor retains its strength."

It is not at all incidental that in reciting all this, particularly the notion of honor, one could just as easily have been talking about the American soldier as the American cowboy. In the past, when the country marched to war, it recognized patience, duty, sacrifice, the possible consequences of battle and the undercurrent of tragedy, and it eschewed hubris. And when the wars were over, America recognized that just as the cowboy was an agent of civilization rather than a force of retribution, so too America must seek reconciliation rather than revenge -- the precept that guided us in redrawing the map of Europe after World War I, and instituting the Marshall Plan after World War II. This was a powerful image, and it appealed, as the western did, to Americans' vanity: the nation itself as the last gentleman in a cruel and unforgiving world.

It was not, however, an image to which the administration of George W. Bush wanted to subscribe. Bush, Vice President Cheney and Defense Secretary Rumsfeld had another idea. In 1991, after the first Gulf War, Paul Wolfowitz, a protégé of Cheney's and Rumsfeld's, and now deputy defense secretary, wrote a white paper outlining prospective American approaches in the post-Cold War period that has become the blueprint for foreign policy in the administration of Bush II. Wolfowitz didn't like the idea of a reluctant warrior, probably because he thought it might send the wrong message to the rest of the world -- a message of weakness. (Being a "wimp" in the administration of Bush I, who had been accused of wimpishness himself, seemed to be the ultimate insult.)

Wolfowitz didn't like the idea of sacrifice or recognition of consequences or humility either, and he certainly didn't like the idea of accepting the tragic dimension of conflict. As he saw it, America had to be unassailable and implacable. It had to be so mighty that it would terrorize any other nation or coalition of nations. It had to convincingly demonstrate that this was now a unipolar world, that the pole was the United States, and there was nothing that anybody could do about it and thus no reason to try. Basically, the country had to become the Terminator.

As aesthetics go, it was a thrilling concept, and it made for a much more vicariously satisfying movie than the western with its moral calculus and uncertainties. It may even turn out to be a successful policy in the long run. But it was also a hard sell in a country that prided itself on its basic decency and sense of honor ... or at least it was a hard sell until 9/11. If you think of 9/11 as the first scene of a Schwarzenegger movie, like "Collateral Damage," where his family is brutally murdered, you realize that it effectively justifies whatever the hero, in this case the United States, wants to do, which is why 9/11 is now the all-purpose rationalization for everything from the invasion of Iraq to the bullying of our allies to the threats to Syria and Iran. With foreign policy suddenly turned into a long revenge movie, the Terminator could at long last supplant the cowboy as the country's model of behavior and repository of values.

And how different those values are! A Terminator, virtually invincible and omnipotent, doesn't do what is necessary; it does what is possible. It acts rather than reacts. It shoots first. It cannot compute reluctance or hesitation except as a ploy. A Terminator harbors no moral qualms, none of the weary obligation or doubt the cowboy has. It is programmed and then follows its program with absolute certainty. (Indeed, in the first Terminator film, the cyborg is evil; in the second, released in the year of Wolfowitz's paper, good.) It does not negotiate or temporize because it needs no one and does not act in concert.

A Terminator cannot make sacrifices and cannot comprehend them. A Terminator has no tragic sense because it isn't subject to the human condition. It exists above that condition. A Terminator is all hubris and nothing but hubris insofar as that term is even applicable. It sees taunting as a psychological weapon. It cannot be reasoned with or reckoned with. It cannot be stopped once it is set in motion. It inspires shock and awe. In short, it is the ideal metaphor for Wolfowitz's, and now President Bush's, concept of American power.

While Americans argue over whether they want their nation to be a cowboy or a Terminator, the administration should be aware that if the Terminator is seemingly indestructible, it is not necessarily infallible. For all its technological capabilities, it can be dogged and harassed and waylaid -- witness not only the first Terminator picture but also America's adventure in Somalia and the early days of this Iraq war. A Terminator may be almighty but it is not nimble. More seriously, it can be victimized by its own sense of indomitability.

The cowboy recognized his vulnerability. He operated with the knowledge of the vagaries of the world and of his place within it -- a knowledge that the current architects of American foreign policy disdain as soft. What they propose instead is to act as if nothing but power exists. And so the Terminator, able to intimidate but not conciliate, plows ahead, inducing fear and wreaking destruction but unable to understand anyone or anything beyond its own certitude and its own brute force.

Meanwhile, the cowboy rides into the sunset.

Shares