Linda Komaroff is curator of Islamic art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where she put together the current show, "The Legacy of Genghis Khan," in collaboration with Stefano Carboni of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. That show, which opened April 13 and runs through July 27, focuses on the cultural effects of the Mongol invasion and the fall of Baghdad in 1258. Salon spoke with Komaroff by phone about the cultural, historical and aesthetic significance of the recent looting of the Iraqi National Museum in Baghdad.

What was your first thought when you heard of the museum looting in Baghdad this past week?

I thought it was devastating. The Baghdad museum collection included Islamic art, but it's known for its antiquities.

Can you explain the difference?

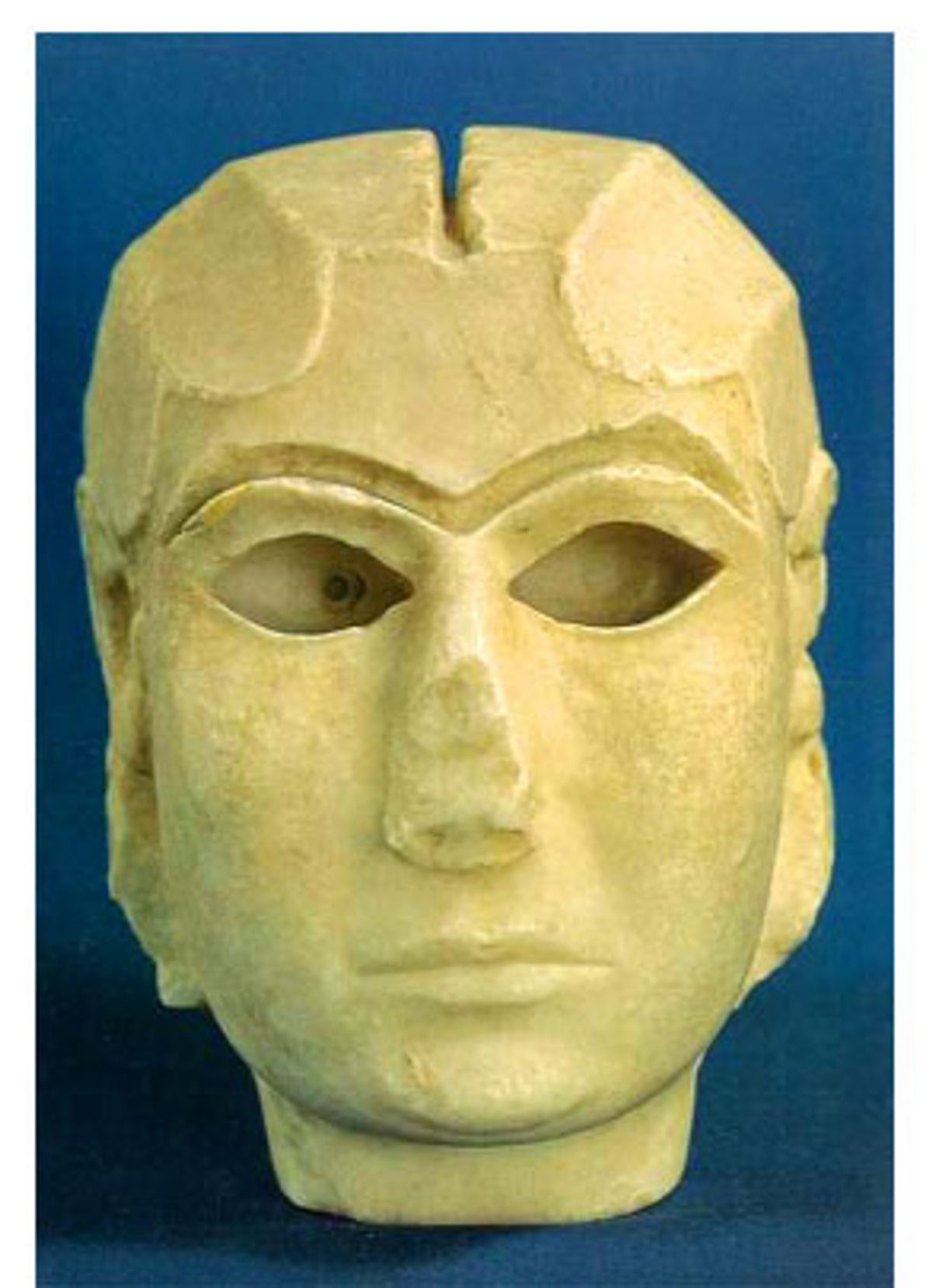

Well, the Islamic era began in the 7th century A.D., so the period of antiquities, of ancient Near Eastern art, is before that. The museum had some of the key monuments of ancient civilization. If you took art history in college and you used Janson -- if you go to the section on Mesopotamia you'll see the marble head of a woman, the eyebrows are hollowed out, the hair parted in the middle. It's from Uruk, an ancient site. There's also the bronze head of a ruler -- he had a bun at the back of his head, his eyes gouged out. Those two pieces were in the Baghdad museum.

Can you compare this with a museum most people would know in terms of its importance?

It's as if someone broke into the Uffizi in Florence. It's comparable to that, it's just that more people in the West are familiar with the Renaissance than with ancient Islamic art.

What is the overall cultural value of the collection that was in the Baghdad Museum?

Mesopotamia, through more modern times, has been the site of continuous civilization -- at least, it's been inhabited for more than 8,000 years -- and the remains of that civilization have been uncovered since the 19th century. So the whole history of about 8,000 years was on view in that museum, at least in part, from 6000 B.C. to works from the Ottoman period in the 19th century. It's a huge amount of time for a museum to cover. For that one region it was very comprehensive.

What is the history of that museum? How did the collection develop?

For about the last 70 years that museum has been the main repository for materials excavated in Iraq. In the 19th century, archaeologists could remove everything they found. In the first half of the 20th century it was usually a split, 50/50, between the finders and the host country. In the second half of the 20th century it's become common for whatever is excavated to remain in the country, whether it's found by a local or a foreign archaeologist. I know a few people who have gone there and one was crying yesterday.

To play devil's advocate, why should someone in Peoria care about a cuneiform tablet or a silver harp in a museum in Baghdad?

There are two different ways they might care. I'll do the less important first: The reason excavation in that part of the world became popular was because of archaeologists who wanted to prove the historical validity of the Bible. Now, someone in Peoria is going to have heard of Ur, because Abraham came from there. But more of interest to Darwinists and to people not interested in proving the validity of the Bible is that we share a common civilization, and that's where it began. A cuneiform tablet touched by someone 4,000 years ago is gone. We are all affected by that. It diminishes all of us. It's not as though we can say, "I didn't come from there." Civilization traces its roots there.

If we want to make it nationalistic, what if we were to lose all copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and someone stole the Liberty Bell? If they had all been in a single museum and someone had come in and taken them all! The pictures and the numbers don't explain the loss. If we were to lose our history it would be devastating. But this is 30 times more because the civilization is 30 times older.

Let's put aside the question of whether the coalition forces should have prevented the looting. That will be debated elsewhere. Now that the artifacts are gone, what can be done? We hear now that the British Museum and the United Nations will send in teams to try to locate the items. What do you think of that plan?

What they would have to do is offer rewards to people to turn in what they've taken -- I heard that one of the senior staff members [at the museum] found glass cutters, which suggests people had gone there knowing there were things in glass cases. Those works of art won't be turned in, even if a reward is offered.

The show you curated, that is up now at LACMA, seems eerily connected to what's happening now.

It's a show about the aftereffects of the Mongol invasion. It begins prior to the conquest of Baghdad by Mongols in 1258. Who knows what history will say of the fall of Baghdad in 2003. But then it was the end of the Caliphate [the 600-year period in which the Islamic world was ruled by a single theocratic ruler, the Caliph] that produced a shift in focus from Iraq being a dominant center of the Arab world to part of the Iranian empire. Iraq is a modern construct, formed in 1921 out of three different administrative areas that were part of the Ottoman Empire. The land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers always existed, but was always appended to or dominated by other parts of the region. It's hard for Americans to think of this, because it's thousands of years of history. With the fall of Baghdad in 1258, Iraq fell into a larger area under the control of Persian culture, until the end of the 16th century. We never envisioned what would be happening now, but the exhibit does include works of art from Iraq, illustrated manuscripts and some calligraphy from Baghdad and Mosul.

Can you think of some items that are particularly important that you would like to see returned?

Nobody knows if everything is gone, or if anything has been found yet. But one site is Ur, where Abraham came from. It was excavated by a joint British Museum and University of Pennsylvania team and the finds divided among three museums, and so it was a very important site, including tombs with a lot of gold that remained in Baghdad. The theory would be that the gold was taken and melted down for quick cash. Most likely the sculptures will resurface at some point or be returned, because they are only valuable to a museum or art collector.

In terms of one piece, no, because my job and my life is involved with art in a museum, helping to preserve and protect it. It's all important, from the least significant to the most. I feel tremendous sympathy for the curators of that museum. Their lives were devoted to this. It must have been horrible for them.

Are there other museums in the world that harbor some of the same cultural artifacts?

The British Museum has the most, outside Iraq. They have some from Ur and the famous Syrian reliefs. The Louvre has some examples of ancient art, and the Metropolitan of course. Berlin has the Ishtar Gate from Babylon. But the loss is threefold -- the artifacts may have been destroyed, but they were also all together in one institution where you could get a full sense of the history. For the people of Iraq, this is their cultural heritage.

Shares