America's New Regional Order in the postwar Middle East faced its first major test this week in Ramallah, as Yasser Arafat, the veteran Palestinian leader, fought for his political life against a coalition of domestic and international forces bent on easing him out of power. Arafat used his rich arsenal of political tricks to hinder the power shift to Mahmoud A'bbas, known to Palestinians and to Israelis alike by his nom de guerre Abu Mazen, who was appointed to the new job of Palestinian prime minister. In the end, Arafat lost, but the peace process still faces daunting odds.

Abu Mazen's appointment has been widely perceived as the key to resuming the defunct peace process between the Palestinians and Israel. The Bush administration has pledged to publish the "roadmap," an international plan to resolve the conflict and take steps toward a full-fledged Palestinian state in 2005, once Abu Mazen's government is confirmed. Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon has announced his intention to meet Abu Mazen and open negotiations with him soon after the new Palestinian interlocutor takes office. A host of foreign ministers and other world figures, led by U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, stands ready to visit the region and push negotiations forward.

The political drama in Ramallah, the quasi-capital of the Palestinian Authority, ended today only hours before the deadline for Abu Mazen to form his Cabinet. In the last 24 hours, pressure mounted on Arafat to succumb to the forces of change. Egyptian intelligence chief Omar Suleiman, a key player in regional power games, came to Ramallah with a strong message from President Hosni Mubarak. British Prime Minister Tony Blair, after the Iraq war Europe's most influential champion of the Palestinian cause, used the telephone. All demanded that Arafat step aside and give Abu Mazen a free hand to put together his Cabinet. The main dispute revolved around the appointment of Mohammed Dahlan, a longtime Arafat rival, to the most powerful and crucial post, that of security chief. Dahlan, from Gaza, is expected to take strong measures to fight terror attacks against Israel, and crack down on extremists. Eventually, with Suleiman's intervention, Abu Mazen had his way, and Dahlan was appointed.

Urged on by Sharon, President Bush had demanded that the Palestinians change their leadership in his major Middle East policy speech of June 24, 2002. The vehicle of this proposed shift was the appointment of a strong Palestinian prime minister, who would take over Arafat's executive authorities and move the veteran leader into a figurehead position. (Sharon's aides referred to the proposed role as "the Queen of England" or better still, "the Queen Mother.")

Gradually, an Arafat-ouster coalition mounted, as the United States and Israel were reinforced by a growing number of European and Arab governments and by a group of disillusioned activists from Fatah, the mainstream Palestinian faction. Members of that group have come to view the 31-month-old intifada as a disaster that has harmed the Palestinian cause and ruined the Palestinian society and economy by bringing on an Israeli reoccupation. They advocate an end to attacks against Israeli civilians. During the winter they tried to reach a wide-ranging cease-fire agreement with the Islamic terrorist groups, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, to no avail.

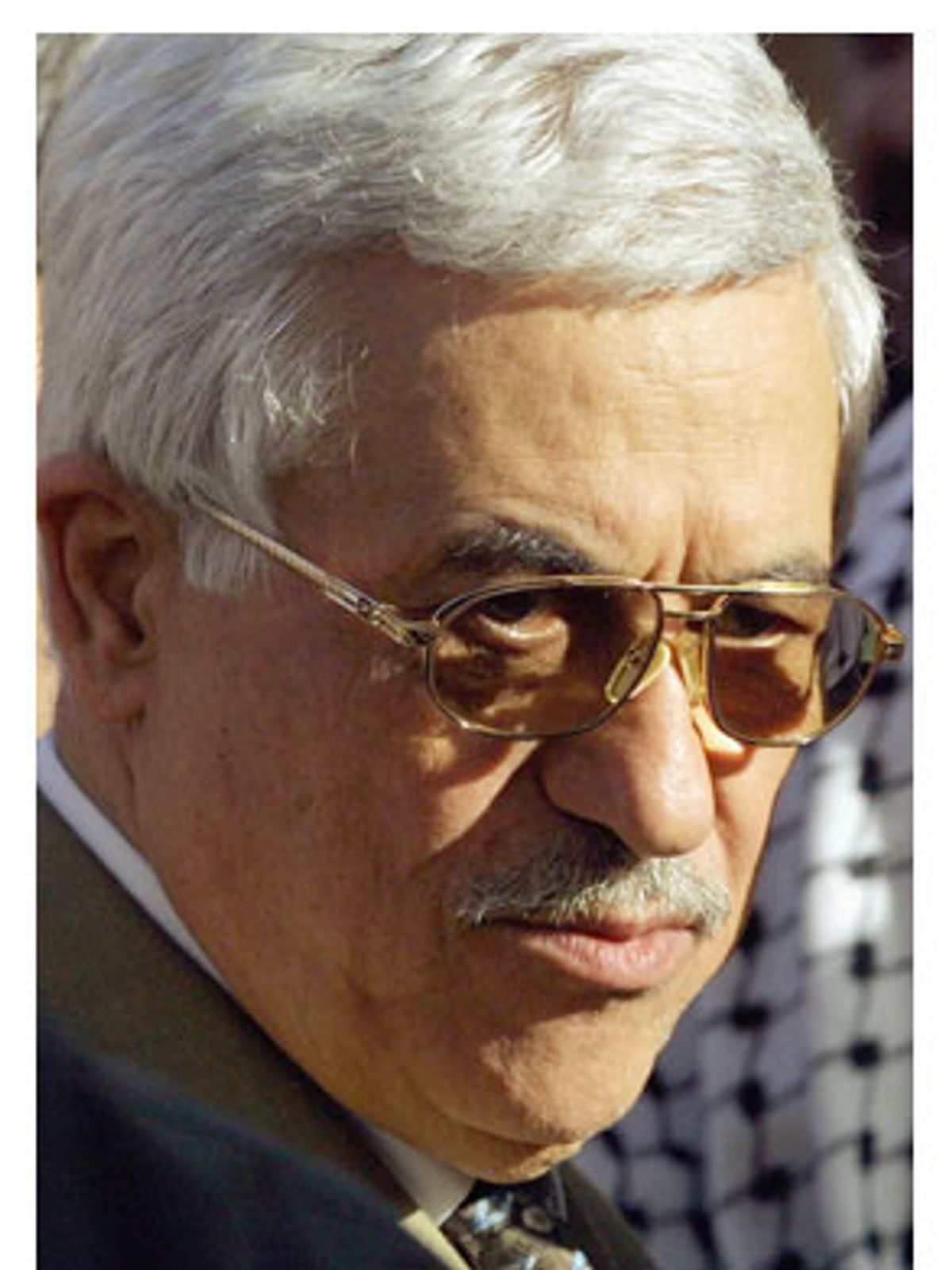

The reformists' chosen conduit for change has been the bespectacled, white-haired Abu Mazen, a longtime Arafat ally who served as second in command in the PLO hierarchy. Abu Mazen, whose family fled from Safed in the 1948 war, played a central role in Palestinian-Israeli negotiations throughout the 1990s, and took part in the failed Camp David summit of summer 2000. His Israeli acquaintances depict Abu Mazen as a moderate on using violence and terrorism, but a hard-liner on the most contentious negotiating item, the Palestinians' claim of "right of return" to their millions of refugees, who fled, or whose ancestors fled, from what is now Israeli territory. For Israelis, the "right of return" idea is tantamount to the destruction of the Jewish state, since Jews would no longer be a majority.

Naturally, most of Abu Mazen's Israeli contacts belong to the political left: people like Yossi Beilin, who negotiated a final-status blueprint with A'bbas in the mid-1990s. However, Abu Mazen has also forged an acquaintance with Sharon. In recent years, the two have met several times at Sharon's farm and at the prime minister's official Jerusalem residence. The Israeli leader views Abu Mazen as a Palestinian nationalist, but a pragmatic one. From his first days in office, Sharon has regarded Abu Mazen as a more appealing alternative to Arafat.

Last month, on the eve of the Iraq war, Arafat bowed to strong outside pressure, delivered by the E.U., U.N. and Russian envoys (the Bush administration has refused to deal with him), and appointed Abu Mazen as prime minister. The war slowed down the Cabinet formation process, as the world's attention was turned elsewhere. Now, with America victorious in Baghdad, the focus has shifted back to Ramallah.

On the surface, prospects for a revived peace process have not been this good since Sharon came to power as the Camp David negotiations collapsed, vowing "not to negotiate under fire." Both sides of the conflict are exhausted, having lost hundreds of kinsmen and suffering major blows to their economies. The United States has done away with Saddam Hussein, the bastion of Arab extremism and rejectionism, and thus removed a major perceived threat to Israel's security. Syria has been put on notice by Washington and is unlikely to foment trouble on Israel's northern front. Bush has also kept his word to Sharon and instigated Palestinian regime change. A year after Israel reoccupied the West Bank, Israelis are relatively free from the horrors of daily suicide bombings, which shadowed their lives only a year ago. Although there are still many terror warnings and attempted bombers are caught every few days, commanders of the Israel Defense Force talk now about "victory" over terrorism. They view Arafat's decline as a decisive achievement, and anticipate a positive turn of events following the Iraq war.

Sharon himself, aware of the changing environment, launched his own charm offensive. In interviews he gave to Israel's three major newspapers last week, on the occasion of the Jewish Passover holiday, the prime minister portrayed an unusually moderate image. For the first time ever, he talked openly about the possibility of evacuating Israeli settlements in the occupied territories. In the past, some of Sharon's aides and political associates had occasionally whispered to reporters about possibly removing settlements in exchange for peace. But their boss had always forbidden them from discussing the subject in public, let alone mentioning it himself. The furthest he would go was to refuse to promise that he would never remove any settlements and make vague hints about undefined future "painful concessions."

"Sharon decided to remove the ambiguity over the settlement issue," explained a senior aide, "since we're at a strategic crossroads, following the Iraq war and the developments in the Palestinian Authority. It's important to show that we hear a certain flap of history's wings, and that we're aware of what we should be doing if the Palestinians eventually fulfill their old obligations." Sharon also faces a strong domestic challenge, as the new economic recovery plan -- based on deep budget cuts -- is approaching its political test under the trade union's threat of general strike.

In recent weeks, the Bush administration has bombarded Israel with demands for "gestures" to facilitate Abu Mazen's hold on power. But since officials in both Jerusalem and Washington acknowledge that offering too warm a "public hug" to the new prime minister might lead Palestinians to regard him as a "collaborator" with the Americans and Israelis, the proposed Israeli gestures involve not Abu Mazen himself but substantive issues like withdrawal from Palestinian-controlled areas, accelerated transfer of tax monies owed to the Palestinians by Israel, removal of settlement outposts and the lifting of closures and roadblocks.

Israel balked at first, demanding a "testing period" for Abu Mazen, to see if he is actually doing "100 percent effort" to prevent terrorist attacks. But that was apparently a mere bargaining position. Last week, an Israeli delegation came to the White House to present Israel's reservations about the "roadmap," headed by Sharon's bureau chief Dov Weisglass. At the meeting, the Israelis presented their list of "gestures": gradual withdrawal from "quiet" areas, where Abu Mazen's people will take responsibility and dismantle terrorist networks, especially in the Gaza Strip; paying back arrears; and releasing Palestinian prisoners from the over-crowded Israeli jails. Removal of "illegal" settlement outposts (i.e. unofficial settlements that even the Israeli government acknowledges are illegal) was off the list, since Israel views this as a "domestic issue of law enforcement."

Without question, the conclusion of the Iraq war has turned up the diplomatic heat on the Israeli-Palestinian issue. Blair, under domestic political pressure to move the peace process forward and show that he got something in return for his steadfast support of America, extracted a commitment from Bush to implement the "roadmap." Sharon has not rejected the plan, or its major components -- a cease-fire, including a freeze on Israeli settlements, to be followed by a Palestinian state within interim borders, which would negotiate the final status with Israel. Sharon had only asked to amend the details, so they would "fit" the speech Bush gave last June, which put the onus for peace almost entirely on the Palestinians. The White House agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to hear the Israeli reservations, and to discuss the plan further with both sides after its formal publication.

All this hopeful activity notwithstanding, there are still a lot of reasons to remain skeptical about chances for peace in the troubled Middle East. The basic, deep gaps between both sides are wider than they were when negotiations broke down in January 2001. It is hard to imagine Sharon, the architect of Israel's settlement policy, offering anything even close to what Ehud Barak proposed at Camp David and Taba -- proposals that Arafat did not accept. Sharon flatly refuses to even discuss the division of Jerusalem, a key Palestinian demand. Moreover, while the Barak government tried to negotiate some face-saving formula to get around the "right of return" issue, Sharon is now demanding that the Palestinians relinquish that claim altogether at the outset of any negotiations. That hard-line position enjoys broad support in the current Israeli Cabinet, even though Israeli negotiators, including Weisglass, fear that it would blow up the process before it begins. Nevertheless, Weisglass presented the "no return" demand at his White House meeting last week with Powell and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice. They have yet to respond.

Ever since he took office, Sharon-watching has been a favorite pastime of politicians, journalists and diplomats in Israel. His recent interviews aroused, as expected, a new wave of speculations and possible solutions to the famed "Sharon riddle": What does he really want? Does he want to go down in history as Israel's de Gaulle or Nixon -- the hard-liner turned peacemaker? Or will he decide to keep his beloved settlements and never give up any of the territory Israel has been occupying since 1967?

Sharon says that at his age, 75, and after his successful reelection in January, he has no further ambitions than bringing "peace and security" to the people of Israel. It is true that his status as "mister security" puts him in a uniquely privileged position to sell concessions to the Israeli public. But there is reason to doubt that in the end he will make those concessions. Sharon is extremely reluctant to take risks, preferring to dictate terms to the Palestinians from a position of strength rather than gamble on goodwill-building measures. And the right-wing majority in his Cabinet makes it even less likely that he will launch a bold peace initiative. A Sharon "yes, but" usually means a courteous but firm "no."

Sharon has issued positive, peaceful declarations time and again in the last two years, but they have never been implemented. Who remembers Sharon's pledge to launch a "Marshall Plan" to revive the Palestinian economy? Or his repeated proposals for locally based cease-fires? Or his pledge to ease the living conditions of non-terrorist Palestinians? Nowadays, Sharon is doing his best to shift the onus to the other side, and make every Israeli concession dependent upon the actions of Abu Mazen and company. But the new Palestinian leader needs time to gain legitimacy in the eyes of his constituents: He can't give up too much to Sharon or Bush, especially not at the beginning of his term of office. Sharon's demands thus seem counterproductive.

The depth of America's commitment to a genuine peace deal is also highly questionable. In recent weeks, Washington officials have reverted to the old State Department "linkage" between Iraq and Palestine. According to this school of thought, which is echoed today by the CIA and the White House, calming the Israeli-Palestinian strife is essential for improving America's stance in the Arab world. Further neglect of the Palestine cause will simply confirm what much of the world already believes, that the Bush administration is Sharon's patsy. Therefore, the United States should now turn its sights from Baghdad to Jerusalem.

Needless to say, Sharon opposes this line of thought categorically, as evidenced by his warning that "Israel will not pay the price of the war." And there is no particular reason to believe that Bush will finally decide to challenge his friend Sharon.

Time after time in the past two years, Colin Powell has stood at some podium or other and promised that he and the president are "engaged" in the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. When the crisis has gotten too hot to ignore -- when the body count has risen, or Washington has faced pressure from its British or Arab friends -- the administration has repeatedly said it would intervene to stop the bloodshed. So far, it has never done so.

Circumstances on the ground seem more hopeful than before, but there is no evidence of a sea change in the administration's "benign neglect" approach to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And the window of opportunity may be closing: Once Bush starts his 2004 reelection campaign, will he really want to jeopardize the crucial Christian evangelical and Jewish votes by pressuring Israel?

Shares