In the fields of northern Iraq, where flowers bloom and the grain is shooting up, the Kurdish village where Shaker Mahmoud Al-Zendi comes from is now only a scar in the ground. He crouches down and picks up a handful of dust. "This is all that Saddam Hussein left of my house. But I swear I will build a new one right on this spot." He has just led his family back from a 20-year internal exile in Iraq's western desert and he fully intends to take back his land -- all of it. There's just one problem: The land is not unoccupied. Iraqi Arabs settled there by Saddam Hussein have been living there for as long as 20 years, and the clashes between the two groups are threatening to create serious problems in postwar Iraq.

Al-Zendi's village was one of hundreds that disappeared in the "Arabization" campaign that Saddam Hussein and his Baath regime initiated in the north of the country, around the oil-rich centers of Kirkuk and Mosul. The campaign started in the 1980s and was actively pursued until the very end of the regime. The aim was to secure the oil regions by getting rid of the troublesome Kurdish population (the Kurds rose in revolt against Saddam in 1982) and replacing them with members of loyal Arab Sunni tribes.

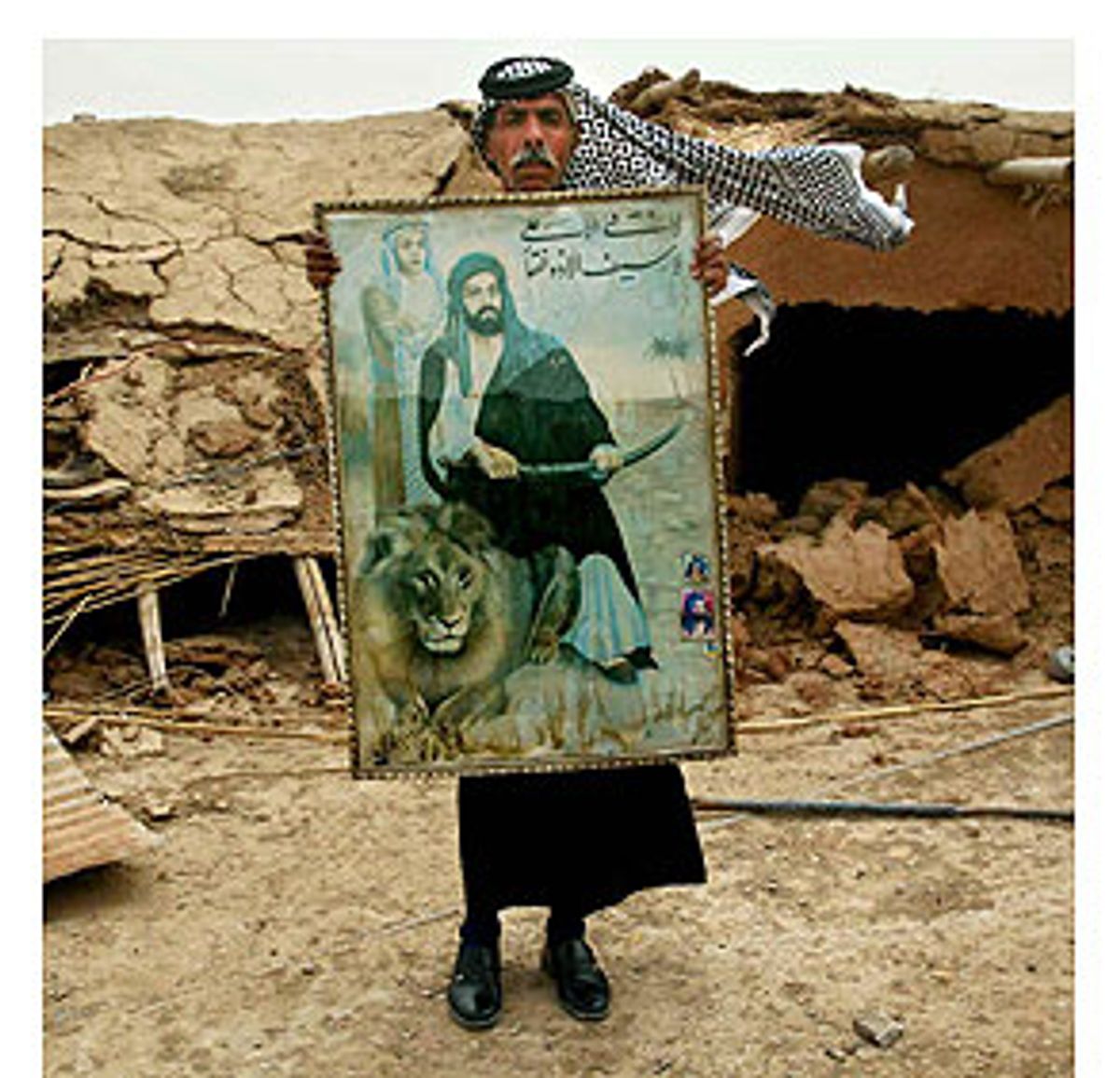

Shaker Mahmoud is furious when he recalls the allegations that the Kurds in the area caused trouble. "Me a troublemaker?" he shouts incredulously. "I came back from fighting for Iraq against Iran at the Faw peninsula in 1983," he recalls. "It had been a terrible battle but when I got home it was worse -- my whole village had been wiped off the face of the earth." His family had disappeared: He had to search for them, then join them in exile. "We were not allowed to return; they always checked our papers. The only way to have a look was to sneak in."

According to Human Rights Watch, which conducted many interviews with expelled families, the non-Arabs -- who also included much smaller numbers of Turkomans and Assyrians -- were allowed to take very few personal possessions and were stripped of all papers except identity cards. The reason for the expulsion was usually their refusal to sign "nationality correction forms" in which they formally changed their ethnic status to Arab. "Many reported that the government continued to ban the use of non-Arab names when registering newborns, and that in some cases they pressured non-Arabs to adopt Arab names upon marriage," the human rights group declared. "In April, the authorities were reported to be giving additional incentives, such as plots of land, to Arabs resettled in Kirkuk who brought the remains of dead relatives for reburial in the city's cemeteries."

This week thousands of Kurdish families started to return to the Dakuk area near Kirkuk from elsewhere in the country. The tide had already started the week before, immediately after the fall of Saddam Hussein, but those came mostly from the autonomous Kurdish zone farther north. Many had fled there when the campaign reached their villages. The Baath party forced most of the families into internal exile, though, in remote and poor areas of the country. Some 200 Al-Zendi families were driven to Ramadi in the dusty and dry western desert toward Jordan.

The Kurds are understandably overjoyed to be returning to their green and fertile fields in the north. On open-bed trucks, whole households and their belongings travel through the night to resume lives that many feel had been on hold since their expulsions. But their return has led to a new problem: Strangers are now living on their lands and in their houses. In many cases they have been there for years. And some of them refuse to leave without a fight.

Both American and Kurdish leaders, well aware that the issue could reawaken ethnic tensions and threaten the country's fragile postwar stability, have called for all Kurdish claims to be carried out through legal channels. But tensions are high and deadly armed clashes have taken place. In the town of Rummana, near Mosul, for example, Arab tribes and Kurds reached an agreement that if a member of either group trespassed in the other group's village, he would be killed on sight. The night after the agreement was reached, two Arabs and three Kurds were killed. Arabs across the north claim they have been threatened, vandalized, shot at and harassed -- with the Americans doing nothing.

Shaker Mahmoud and his family are red-hot with anger when they talk about the interlopers.

"That is still my land and I asked them to leave a few days ago when I first came back alone, to see the place for myself," he explains. Shaker Mahmoud points at several villages in the distance and says that his land stretches even beyond them. "They are sitting on my land and I want them to leave but they just said no." Calling the villagers "thieves and gypsies," he claims they belong to Arab and "Bedouin" tribes and that they were paid large sums of money by the Baath party to settle on his land.

He is not quite sure what to do next. In the meantime he has ordered his men to set up tents near their old village in order to stake their claim.

At the Dakuk checkpoint returning families are being met by officials from the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which controls the area. Nur Eddin Daoudi is a political officer who says his task is to help smooth the return for the exiles. "We are here for our people who have suffered so much over the past 30 years under Saddam Hussein," he says. Daoudi does not want to talk about practical matters during this emotional time. He sidesteps questions about deeds, maintaining that all the returnees are in the possession of the proper documents, proving their ownership of the land. But some of the returning Kurds themselves admit that not all of them have documentation -- not surprisingly, perhaps, considering that the Baath regime typically refused to give the exiles any papers except identity cards.

The PUK's aim is to reverse the Arabization that was carried out by the Baath. For this purpose, says Daoudi without even the slightest hesitation, some 750,000 "Arabs and Bedu" in the district of Kirkuk will have to leave. They were "instruments of the Baath" in the Arabization of the region. "They will have to go back to their home districts," says Daoudi. "Some of them are not even real Iraqis." But the PUK will respect their human rights, he says. "We suffered from the Baath and will not do the same to others." The Arabs will get one month to find homes and jobs elsewhere.

"We don't have anywhere else to go," says Sheik Awad Bardi Owgla in the village of Al-Wahdeh, which means "unity" in Arabic. It is one of the villages that Shaker Mahmoud Al-Zendi had pointed at angrily. The local members of the large Al-Shamar tribe are anxious and angry. Over the last couple of days they say they have been attacked by several Kurdish claimants and they have been threatened with evictions. "We live here legally, just like everyone else in Iraq," says Owgla. "How can people come and tell us to leave?" He blames the Americans who "have got rid of the government and pitched the country into chaos."

For centuries, the Al-Shamar and their cattle roamed large tracts of lands "from the Syrian border region to the North of Saudi Arabia," tells Owgla. In 1973, the government forced them to register and give up their nomadic existence. He explains that, indeed, before 1974 the tribe did not have any nationality because of their wanderings. The government changed that and assigned them lands near Dakuk, the same way they did, according to him, with the neighboring Kurdish tribes.

"Those Kurds are liars," says Owgla. "They were given their lands by the government just a few years before us. Most of our land was also state land and the rest we bought from individuals." Owgla's account tallies with a PUK guideline that states that everybody who registered in the area before 1971 can stay; families who registered later have to leave.

Owgla concedes that his village may have taken over some Kurdish lands after their expulsion in 1983 but indicates that the issue can be negotiated. Another Shamar Sheik in the north of the country also says there have been informal contacts between the Arabs and the leader of another Kurdish faction, Massoud Barzani of the KDP. He too concedes that the Kurds have a claim to the land, because their expulsion was unjust. "But it was done by the government, and now we have to sort it out so that everybody can live together." The sheik admits that the Al Shamar tribe was close to the old government but doesn't see that as an obstacle to good future relations with the staunchly anti-Baath Kurds.

In Al-Wahdeh, though, Owgla says that the Al-Zendis and other Kurds in the area are shooting at them, and complains that the Americans are not helping. "The Americans should protect us. They protect the oil fields in Kirkuk but not our families." As he is speaking inside the large communal gathering house in Al-Wahdeh, the villagers sound the alarm. "They have set one of our sheds on fire," shouts one of the watchmen, pointing at a plume of smoke in a distant field. Owgla immediately orders the villagers to get their arms and take up positions on the rooftops.

Across the fields, the Al-Zendi men are busy getting re-acquainted with their land. They strongly believe that they are the true victims, not the Arab tribe in the village. "Our village was destroyed, all our possessions lost, our wells were destroyed and we lost a generation of children who could not be educated because of the trauma, the language difficulties and the attitude of the authorities," says Shaker Mahmoud. Nor are their difficulties over yet. It will take a long time to rebuild the village. The tents are for the men only; the women and children will stay near Dakuk in a house that Mahmoud Shaker lived in 20 years ago.

"We call this now the Baath neighborhood," one of the children chirps merrily. The house is still there, Shaker Mahmoud says, because "it was taken over by a member of the Baath. He left some 20 days ago; when I heard it, I immediately sent some men to take it back." Now the women are cleaning the house out to get rid of all signs of the last occupant. "He was a pig," says Shaker Mahmoud's wife, Khalida Jimma. "He lived here for 20 years and then when he left he tried to set it on fire."

Still, she is overjoyed about being back in her home region. "In Ramadi I worried all the time. I told my children not to go out because they could be picked up for the least offence," she sighs. "Even we older people had to be careful about the way we addressed young Arab children. We were less than animals to the people there."

The young children are walking about in a bit of a daze. This is the first time they've seen the home of their parents: they were born in Ramadi. "I hated Ramadi," says 10-year-old Hawla. "The people there were really mean to us." She doesn't miss anything she left behind, neither her school nor her friends. "This is our place," she says. "I already feel at home."

Shares