On Monday afternoon, we were on our way to the Abu Ghraib prison complex from Baghdad and I was having second thoughts about the trip. It didn't have to do with the security situation. I was nervous because we were bringing a man back to the place where he had been tortured and imprisoned for eight years, and it seemed like a cruel thing to do. We wanted his impressions of the place.

The man, Hamid al Mokhtar, is not a criminal. He is an Iraqi novelist and poet condemned for his writing, and he is a survivor of the vast killing machine set up by the regime. The system he defied by continuing to write was designed to destroy the minds and bodies of those who threatened it, and everyone in Iraq knew this. Other Iraqis spent their lives trying to stay out of its path, or cooperating by selling others out, but Mokhtar devoted himself to writing his novels and poems with very little hope that the regime would ever come to an end. He knew his work would get him in trouble, and it did.

The writer looked out the window of the car as we passed the burned-out shells of vehicles destroyed by the U.S., and when a bird brushed the windshield he caught the moment of the bird's escape with a quick nod. The man watched the bird and remembered its motion. Mokhtar is loved by the writers and artists who remain in Baghdad, and mentioning his name opens doors in this small community of intellectuals, many of them still in shock after the bombing and occupation. On Tuesday, a friend was visiting the national library, which is guarded by a writer who sits in a chair in front of the building. The writer sits there because he wants to protect it from looters. When my colleague mentioned that she knew Mokhtar, the man saluted. In the Arab world a Mokhtar is a village leader, a respected man.

Mokhtar, a slight man with gray eyes and a white-edged beard, is the author of "Al Jemel Bima Hamel," a novel about Iraq under Saddam. The title loosely translates to "The Heavily Burdened Camel," an expression used by Iraqis when they have returned home to find their place looted and stripped bare. At the moment he told us the title of that novel there were people all over Baghdad looting and burning unguarded buildings.

The highway to Abu Ghraib is modern and the ride reminded me of driving in California. Baghdad is a city of 5 million people and it was warm and the air was dry and dusty and that reminded me of Los Angeles. It's a graceful city, particularly by the Tigris where there are strands of palms and eucalyptus trees for shade. Just before we left with Hamid al Mokhtar for Abu Ghraib, we had lunch with him in a cafe in a neighborhood called Waziria. In Arabic, wazir means minister. Waziria is the diplomatic district, but it is a place where Baghdad intellectuals congregate, and they are just now returning from exile. Mokhtar too is returning from a kind of exile. In the cool basement of the restaurant, we listened while Mokhtar told us a prison story, which he said was a kind of joke.

There was a guard at Abu Ghraib who was in love, but he had a problem. The guard wanted to write a love letter to his girl. But he did not know how to write a love letter, and knew that if he tried, it would come out all wrong. So Mokhtar agreed when the guard asked him for help. The writer agreed because it was the only way he could get fresh air, so he wrote as many letters as he could for the man. When Mokhtar wrote a love letter, the guard allowed him to walk outside in the exercise yard and breathe air that did not smell like a crowd of men in bad conditions. The guard loved the girl deeply and Mokhtar made sure the letters captured the most intimate details of their life. Mokhtar listened and wrote it all down, with passion. Writers always end up in the love letter trade in prisons.

"The problem," he then told us, "was that during a routine interrogation, and this one was very bad, they covered my eyes and took me to the torture chamber so that I couldn't see who was doing it. It was terrible and I cried. But after a while the blind slipped and I saw that it was the same guard who asked me to write the love letters." Mokhtar said he was amazed that it was the lover who was doing the brutal work.

When Mokhtar told us that the story was a kind of joke, he was laughing at first, not because it was funny, but because it was incomprehensible. When he was talking about the love letters it seemed at first to be a happy memory and the story then dissolved into blackness.

Mokhtar, unlike many of the other inmates at Abu Ghraib, was a political and had already been arrested several times by the mukhabarat in the early '90s. After finding an anti-Saddam manuscript, the police took him to Abu Ghraib after a month-long interrogation and the judgment of the revolutionary court. He was tortured not once, but regularly.

Even inside the prison, the authorities did not trust him, and gave him the bed directly across from a man who worked for the party as a spy. They did not want him to write, although they allowed him to manage the library, which the prisoners were too frightened to use. The men thought that if they checked out a book, the guards would use it as evidence against them. Mokhtar slept during the day to escape the prison and wrote at night using the paper his family brought him when they visited.

Like many dissident writers who do not go into exile, Mokhtar wrote much of his work in secret. Because the censor read all the novels the Iraqi writers bothered to submit for publication, he refused to submit his work. Mokhtar had only one officially published novel in his home country. His other novels were smuggled out and published in Spain and the Netherlands, but he has never seen them in print. When he told us that he'd never seen his novels, he shrugged, but I caught a deep sadness, because he wanted to see them alive in the world. In Europe they were perched on bookshelves, but inside Iraq his novels were circulated secretly among readers, as laser-printer samizdat. Someone would print out an edition from a computer and then use a Xerox machine to make copies. The readers passed the copies around. This is how Mokhtar is famous here, though he never had the benefit of being promoted by a publisher. He told us that his literary heroes are James Joyce, William Faulkner, T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf.

As we drove outside Baghdad and saw the twisted burned things on the road, the writer looked out at the scene and said nothing. We didn't know what we were getting into. At the turnoff for Abu Ghraib, Mokhtar told the driver where to go, and directed him toward the gates. Abu Ghraib was just two words to us before we saw it for ourselves. It is a prison city, a gulag, a mass grave. It is enormous, enclosing at least four square miles, surrounded by high walls and guard towers. The words inscribed over the prison read, "No life without the sun, no dignity without Saddam." We were about to be presented with evidence of an extraordinary crime. It would fill our eyes, noses, ears.

Mokhtar left Abu Ghraib in the general amnesty in late 2002 after eight years. The news ran a clip of dazed prisoners carrying a few possessions out of the place while women, mothers, wives and sisters held photographs of their missing, demanding answers about their fate. On Monday, April 28, he went with us back to the prison to show us his cell. Inside it there were places he wanted to go.

The light was failing and by the time we reached Abu Ghraib it was late afternoon. Once through the gates we saw the looters driving around the complex taking anything of value. There were people driving pickup trucks and earthmovers, children running from place to place. Whole families wandered around looking for scrap they could carry out and sell. Packs of wild boys carried lengths of conduit and walked down the corridors smashing windows for fun. When we said hello, the boys would stop and greet us in a cheerful way. From time to time there was a rifle shot in the complex but no one paid attention.

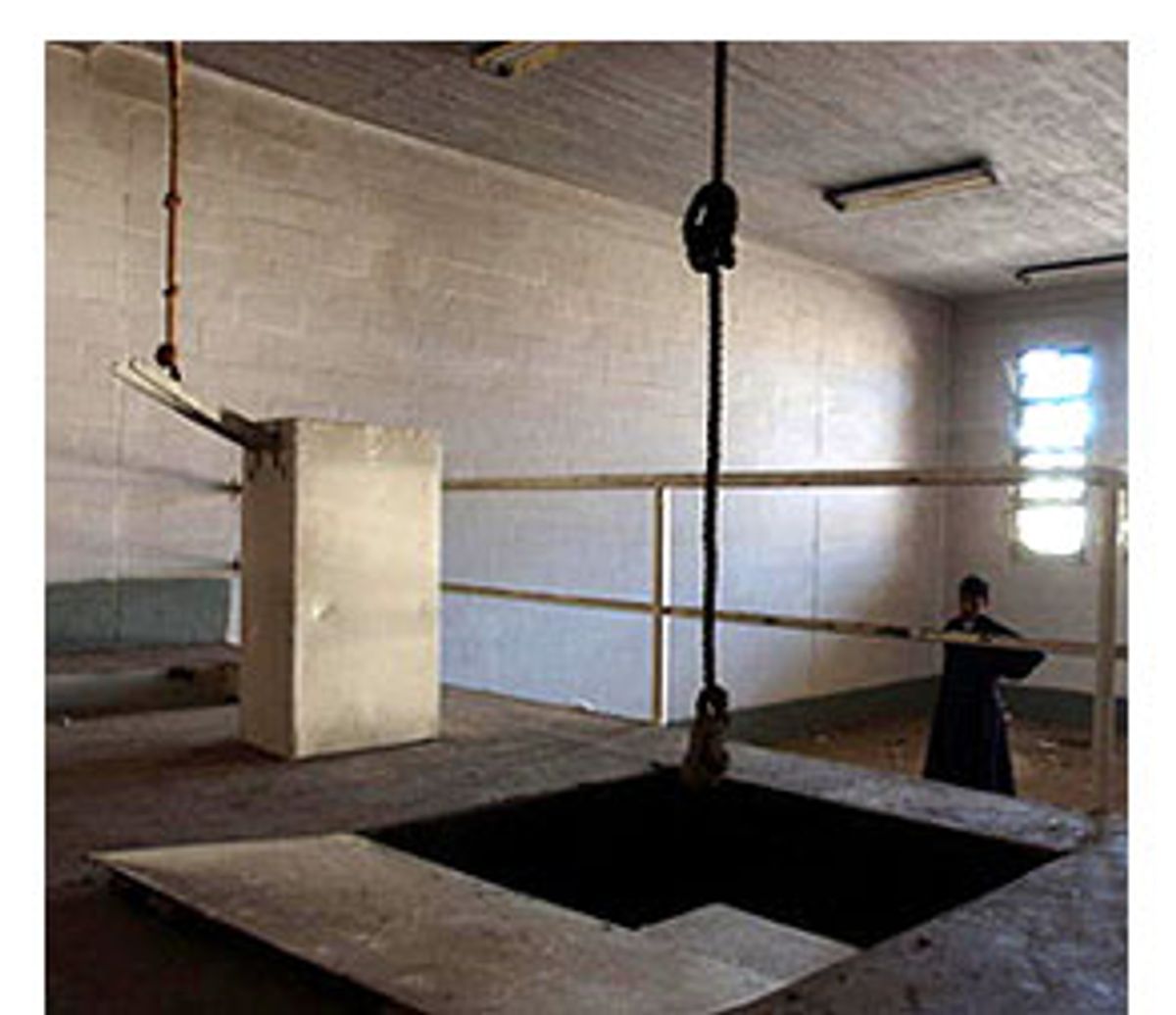

Hamid al Mokhtar led the driver to the building that held the execution chamber. It was a low structure near the high outer walls of the prison. Inside there was a room that looked like a garage built on two levels. A ramp went from the lower floor to an upper floor about halfway toward the ceiling. A prisoner walked this ramp to a loft where there were two trap doors in the concrete, and above those two trapdoors, there were two thick ropes, like the kind used for securing ships. There were no lights and the windows were slits in the concrete walls. The execution chamber had a smell and I cannot describe it. An executioner pulled levers to release the trapdoors and kill the men. What struck me about the nooses, aside from the fact that the looters had avoided touching them, was how well-used they looked. The nooses looked blackened and greased.

We saw the place where the bodies were stored, we saw the bathrooms where the men were allowed to wash themselves one last time. We saw further implements of torture demonstrated for us by a few local men who knew how they worked. As we walked around the chamber Hamid al Mokhtar was quiet and wanted to show us his cellblock, but he was definitely not feeling well. I asked him if his friends had come here and he said yes, and that was all.

Outside in the sunlight, Mokhtar pointed at a large cellblock next to the execution chamber and explained that it once held 500 men, all of them condemned to death.

We drove to Mokhtar's cellblock, and he showed us the exercise yard and looked at the sky above it. Mokhtar showed us where he slept and pointed to a portrait of Saddam on the cellblock wall and said that he is the last prisoner left in Abu Ghraib. We laughed when he said it. Down the hall was a room with concrete tables and benches where the prisoners ate, but in time the prison had become so crowded that the authorities were having men sleep on the tables. Mokhtar said that when women would come to visit their husbands, the guards would leave them in the refectory and the prisoners would protect the couple from the guards while they had sex. "There were a lot of babies born that way," said Mokhtar, "We called them the children of Kanay." Kanay is a nickname for Abu Ghraib.

On our way out of the cellblock, we passed a wall where a door and a window had been bricked over and then covered with a steel sheet. Mokhtar was curious about what was behind the brick. Through a hole in the wall we saw another wing of the prison that looked the same as the others. There wasn't any access to it from our wing; it had been blocked off. The exercise yard was closed off as well, and only recently opened by looters who had torn down a wall. "There is something we called the closed department. The men in the closed department could not receive visitors. No one could have contact with them. And when the amnesty came, it did not apply to them, and they were all killed," Mokhtar said.

Earlier, we asked him how the country's violent past should be handled. He replied, "We don't want revenge, we want the judgment of the law and not of the person. I feel now that maybe there are no intellectuals, and that some people will try to kill the people responsible for this."

On our way out of the prison, we went outside to a place where a man said he saw a body buried. When we found the place there was the sweet, rotting smell. We looked down into a pit with pieces of corrugated steel and a swarm of flies. It was Mokhtar who stepped down into the pit and moved the steel sheet so we could see what was underneath it, because we were afraid to look. The stench was terrible here, much worse than the other places. Worse than the graves at Mosul. After Mokhtar, the novelist, pulled the sheet away from the pit, there was a decomposing body that had been eaten by dogs. The man had been killed recently. There were other corpses buried there but we did not look. Mokhtar looked at the pit but didn't say anything. We moved around and didn't know which questions to ask.

Near the pit with the corpses, there was a freshly dug trench, about 60 feet long and empty except for water. The people who killed the men did not have time to put them in it. I had seen these before outside of Mosul, exactly the same method of burial. We looked around and saw that new foundations were being laid for new cellblocks. Abu Ghraib was still growing when it finally died.

I asked Mokhtar what he thought should happen to the place, and he said, "It should be completely destroyed, every brick."

What was he writing now? "I am writing a collection of poems called 'Under the Red Sun.' It is a eulogy for our lives," said Mokhtar.

Shares