Most thrillers rely on a visual vocabulary of darkness and claustrophobia -- murky compositions and journeys into enclosed spaces -- to draw you into their paranoid universe. In John Malkovich's graceful yet gripping debut as a film director (he has directed many stage productions), he understands that a realm of fear can also be constructed from air and light. The resulting movie, "The Dancer Upstairs," is a haunting and often beautiful work, part doomed romance and part political thriller, that demonstrates the adult command of the medium Malkovich has always demonstrated as an actor.

You'd expect Malkovich to possess an exquisite sense of aesthetic detail; even when playing a queeny villain in a Hollywood movie or mocking his own image in "Being John Malkovich," he always seems to be the kind of guy who notices the linens and knows which fork to pick up first. "The Dancer Upstairs" definitely doesn't disappoint on this level. It begins with a group of people in a car on a rural road shadowed by mountains as they run down a policeman, and ends with a handsome man standing outside a set of glass doors watching his daughter dance while his face registers a complex journey from joy to heartbreak and perhaps back again. In both scenes we hear a live recording of Nina Simone performing Sandy Denny's "Who Knows Where the Time Goes," with a long, talky, eccentric introduction. There's no obvious connection between these moments, or between them and the song, but in some way the combination is masterful. It has something to do with the futility and nobility of human dreams, I think, and also with the fact that we can't be in the world for any length of time without hurting ourselves and other people.

"The Dancer Upstairs" is full of stuff like that. It's a sophisticated film, a thriller for audiences willing to think, but its primary currency is emotional rather than intellectual. It's never self-consciously slow or arty or inscrutable. The man outside the French doors at the end of the film is Agustin Rejas (Javier Bardem), a sleepy-eyed, depressive and fundamentally decent cop worthy of being a Raymond Chandler hero. A leading detective in the capital city of an unnamed South American country teetering between a fascist dictatorship on one side and a fanatical Marxist rebellion on the other, Agustin is just holding on -- to his wife and daughter, his sense of integrity in impossible conditions, his belief in the possibility of a normal civil society.

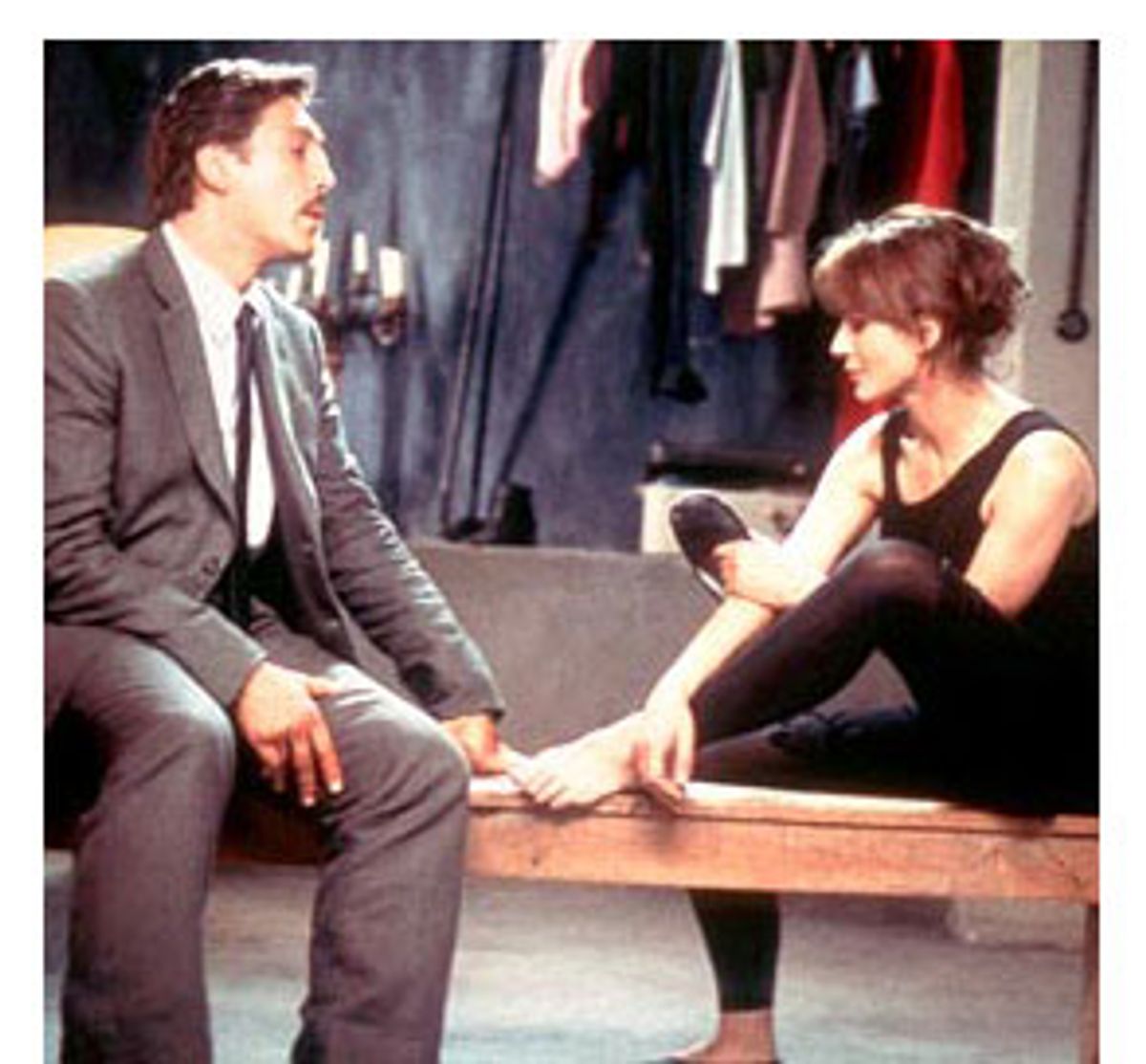

But none of the things Agustin is holding onto will stay solid, and in Bardem's subtly shaded performance, all the rage and hope and lust and despair inside the man start to leak almost visibly from his pores. He's fond of his attractive, affectionate and almost aggressively shallow wife (Alexandra Lencastre), but he doesn't really love her. The rebels have begun a macabre propaganda assault in the capital, hanging dead dogs festooned with dogmatic slogans from the lampposts, sending children to assassinate political leaders and cutting the power every night for agitprop fireworks displays. When Agustin and his team of detectives try to do their work, any suspects they apprehend -- along with plenty of innocent people -- are promptly "disappeared" by government death squads. His only refuge is Yolanda (Laura Morante), the beautiful, world-weary woman with the crooked smile who teaches his daughter's ballet class, with whom he establishes an unstable flirtation.

Adapted by Nicholas Shakespeare from his acclaimed 1997 novel of the same name, "The Dancer Upstairs" is largely based on the torment endured by Peru during the Sendero Luminoso, or "Shining Path," rebellion against that nation's authoritarian government in the '80s and early '90s. Led by a charismatic philosophy professor named Abimael Guzmán, known to the movement as "Chairman Gonzalo," Sendero became a sort of last stand for the most pathological version of revolutionary Marxism. The rebels' daring and theatricality captured the imagination of left-wing sympathizers all over the world, but their vicious and seemingly pointless brutality -- using dogs, chickens and even human children as suicide bombers in indiscriminate public attacks -- eventually alienated everyone except their most fervent supporters. (Some of whom may still be found on the Internet.)

In Shakespeare's screenplay the renegade academic becomes "President Ezequiel" (Abel Folk), but like Guzmán he has anointed himself the "Fourth Flame of Communism" (after Marx, Lenin and Mao) and is fond of spouting disconnected nuggets of wisdom from Kant and the Old Testament prophets. Filming in the clear air and brilliant, high-altitude light of Quito, Ecuador -- Peru, with its tenuously restored democracy, remains a bit jumpy about all things Sendero -- Malkovich and cinematographer José Luis Alcaine establish an almost tangible mood of creeping anarchy. Guerrilla arms smugglers and secret police operate by daylight on the city's seemingly normal streets. As the killings accelerate, Agustin reflects that there's no way to know whether those responsible are guerrillas or student radicals or troops or government agents or the police themselves. At night, armies of desperately poor Indian children slather posters of Ezequiel's eyes -- marked "Miles de Ojos," or "Thousands of Eyes" -- on sidewalks, walls, buses.

Agustin himself is part Indian, and we learn that many years earlier he had to watch while government troops seized his father's coffee farm in a rural region far from the capital. Trying to size up his loyalty, a gruff superior asks him about that episode: "Do you have a feeling about that? Or perhaps you are the Gary Cooper type?" Both are true, of course. Agustin knows that the impoverished masses have a tremendous grievance against their society, but never entertains the notion that a bloodthirsty uprising is the way to satisfy it. (As the same superior says of Ezequiel, "It's a pity he had to bring all that philosophy and murder into it. It was perfectly understandable without that bullshit.")

Even as the worsening disorder in Agustin's country, and his own hunt for Ezequiel, pull him ever closer to Yolanda, he remains the Gary Cooper type. In Bardem's remarkable portrayal, played as much with posture as with spoken language, we can see that Agustin won't let himself descend to what he regards as emotional and moral anarchy, even if he has to break his own heart in the process. Shakespeare's novel has been compared to the work of Graham Greene, in its combination of moral puzzler and political intrigue, and Malkovich's sensitive and spacious direction, alive to the multiple human possibilities of every moment, reminds me of Neil Jordan, the most Greene-like of directors.

I don't find the denouement of Shakespeare's story completely convincing (if you want to avoid spoilers, don't read too much about the real-life Guzmán case) and I have mixed feelings about Malkovich's decision to cast a group of fine Spanish-speaking actors -- and then have them speak English. Such things are necessary and widely accepted in the international film market, and you get used to it as the film goes along. But Bardem, for instance, is sometimes difficult to understand, and there's something awkward and Hollywoodish about the whole idea. Happily, these quibbles detract only a little from this simultaneously tragic and creepy motion picture, a densely involving experience that signals a new direction in John Malkovich's career -- and that will leave you wondering where exactly the boundaries lie between terrorism, fascism and ordinary life.

Shares